Anxiety over the possibility of official action, led either by policy pronouncements or by interest rates, has heightened as the euro has surged to a two-year high against the dollar.

Indeed, since the minutes of the Federal Reserve’s June meeting were released on July 10 – in which the US central bank backtracked on proposal to consider tapering its asset purchases – EURUSD has risen more than 10 big figures and now threatens to break through $1.40 for the first time since October 2011.

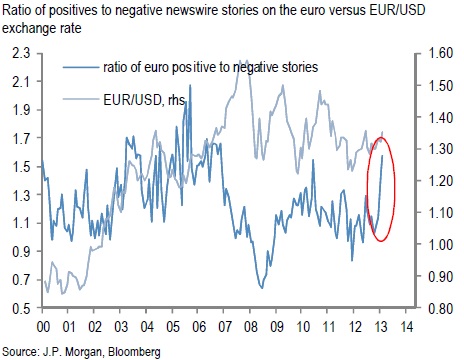

As John Normand, head of FX strategy at JPMorgan, points out, the euro suddenly has a lot of fans. He notes, as the chart below shows, that by some measures the single currency has not been so popular since the heady days of 2007, before the financial crisis, when the European Central Bank was tightening monetary policy, the Fed was easing and the world’s foreign-currency reserve holders were diversifying away from the dollar.

“Fast forward six years and history is rhyming faintly,” says Normand. “The ECB balance sheet is contracting rapidly versus the Fed’s, and Washington’s dysfunction has fanned speculation that the world’s reserve holders should at least renew their passive diversification out of dollars.”

| The euro has a lot of fans |

|

Concerns that the euro’s ascent will ring alarm bells among European policymakers have been heightened by the fact that the last time EURUSD approached current levels, in February, the ECB took aim at the single-currency’s strength.

Then, Mario Draghi, ECB president, helped cap gains in the euro. He said during the central bank’s February meeting that: “The exchange rate is not a policy target but it’s important for growth and price stability and we’ll certainly want to see whether the appreciation if sustained will alter our risk assessment as far as price stability is concerned.”

So far, however, the current bout of euro strength has provoked no reaction from policymakers over price stability.

Indeed, Derek Halpenny, head of global markets research at Bank of Tokyo-Mitsubishi UFJ, believes EURUSD will have to trade higher to provoke such a reaction from the ECB.

That is because studies from the ECB and OECD suggest that a 10% appreciation of the euro on a trade-weighted basis would shave between 0.2% and 0.3% off the annual inflation rate in the year following the euro move.

The current 2014 inflation forecast from the ECB is 1.3% and has been in place since March. Before that, the December 2012 forecast stood at 1.4%.

Halpenny says given that since the December 2012 forecast the euro trade-weighted index has risen by 7%, and since the March forecast it has risen by 3%, the fall in the annual eurozone inflation rate due to the single-currency’s strength is likely to mean it will drop just 0.1 of a percentage point below the current target.

Thus he believes the euro will have to move higher to substantially undermine the ECB’s inflation-fighting credentials.

“It would probably take a EURUSD move well into the $1.40 to $1.45 range for the ECB to act due to concerns over undesirably low levels of inflation,” he says.

| Trade-weighted euro hits multi-year highs |

|

In fact, the signs are that the ECB is sanguine over euro strength, with Austrian ECB board member Ewald Novotny saying on Tuesday that the eurozone will just have to live with the strong euro.

Still, living with a strong euro will be hard, just as living with a strong yen was not easy for Japan before the onset of Abenomics.

Steve Barrow, strategist at Standard Bank, says he is not surprised by Novotny’s comments, however. “We have always believed that ECB members have seen stability and strength of the euro as sacrosanct throughout the whole of the debilitating debt crisis,” he says.

“While the eurozone could have let one, or more, bond markets go, the euro had to be defended at all costs. And rather than seeing euro strength as a curse, the ECB will have seen it as a vindication of its hard-nosed policies towards things like quantitative easing.”

Those policies have produced two things that are supporting the euro: low inflation and a strong balance of payments. Indeed, eurozone consumer price inflation is well below the ECB’s 2% target, while the region’s basic balance has moved from a deficit of around €100 billion in 2008 to a surplus of around €200 billion now.

Of course it has not been a one-way street for the euro. Those positives of low inflation and a balance-of-payments surplus have been born as a result of austerity. The tensions produced by that austerity have flared up from time to time in recent years, provoking speculation over the break-up of the single currency and sending EURUSD down towards the bottom of the $1.20 to $1.50 range that has prevailed since the eruption of the financial crisis.

As Barrow notes, right now, those tensions have eased, allowing EURUSD to head back towards the top of its range.

The longer-term question is whether EURUSD will break out higher out of that range, provoking speculation that the ECB has been too successful in preserving the stability and the strength of the euro.

Could the euro, in other words, get trapped in an era of strength similar to that of the yen?

The yen’s strength, after all, stretches back through Japan’s so-called lost decade and was built on deflation and a strong balance-of-payments position. The tide only turned for the yen after the Fukushima nuclear disaster triggered a collapse of Japan’s trade position through higher oil imports and after prime minister Shinzo Abe targeted higher inflation and a weaker currency.

Barrow says there is certainly a similarity between the euro now and the yen before last year, with the single currency potentially condemned to a period of excessive strength based on low inflation and a strong balance-of-payments position that is borne of fiscal austerity, a hard-nosed ECB and dire economic growth.

He says, however, that there is a crucial difference between Japan and the eurozone that makes him believe that the $1.20 to $1.50 range in EURUSD that has prevailed since the financial crisis will persist.

“We suspect that the political and socio-economic climate in the eurozone is very different from Japan,” says Barrow. “The Japanese were very quiescent during the lost decade in a way that we’ve not seen in the eurozone before now – and we don’t expect to see in the future. This leaves us feeling that the EURUSD range will stay in place.”

Still, with EURUSD sitting more than 10 big figures away from the top of that range and few signs, for now, of renewed strains in countries on the periphery of the eurozone, that still leaves the way open for further gains in the single currency.