Côte d’Ivoire's successful $1 billion issue this week, which was four times oversubscribed and carried a modest new-issue premium, perhaps illustrates a growing disjuncture between the views of economists and portfolio managers, where market technicals – such as supply, demand and liquidity – can override credit fundamentals in allocation decisions.

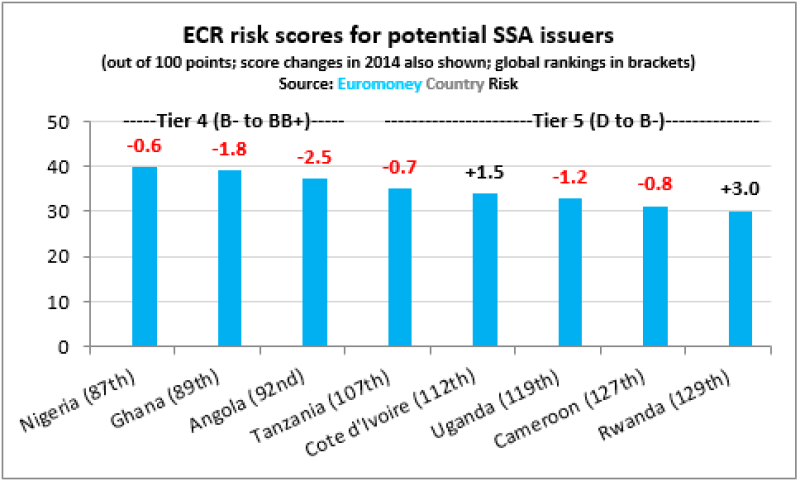

Country risk scores for borrowers considering debt sales this year are either sliding or are still extremely low in a region where IMF and other creditor support is often necessary to quell balance-of-payments pressures, and where capital inflows could be at risk as the region faces up to new threats.

Sub-Saharan issuance has amounted to a one-way bet in recent years, with yield-hungry investors that are seeking out alternative portfolio options creating a mismatch between demand and supply. This, in a region renowned for its relatively high economic growth rates, averaging 5.4% in real terms between 1996 and 2005, and even higher since then despite the brief slowdown in 2009 induced by the global financial crisis.

However, as the chart (below) illustrates, economists consider that risks among core borrowers are increasing or remaining uncomfortably high.

(The ECR survey polls more than 400 economists and other country-risk experts regularly for their opinions on 15 key economic, political and structural country-risk indicators, which are then added to values for capital access, debt indicators and credit ratings to provide a total risk score.)

Several countries have been affected by falling commodity prices, notably the negative oil shock since mid-2014, which has weakened the creditworthiness of Angola, Nigeria and other large hydrocarbons producers on the continent.

Brent blend oil prices have nudged back up above $60 a barrel this February, but are still far from the levels of June 2014.

The country risk score of Angola, which is considering a debut Eurobond issue this year, fell 2.5 points in 2014 to a lowly 37.35 out of a maximum 100 points.

Trouble in Abuja

If economic and political factors are playing on investors’ minds anywhere in the region in the short term it is with regard to Nigeria, argues Samir Gadio, head of Africa strategy at Standard Chartered Bank, and a regular contributor to the survey.

“There are three main issues,” he says. “The oil price has weakened, the currency is under pressure and there is uncertainty surrounding the [March 28] elections.”

Nigeria is considered safer than other prospective bond issuers, but its score has fallen and the sovereign is still regarded as tier-4 (speculative grade), falling to 87th in the ECR global rankings.

Comparisons of its risk indicators in the chart (below) highlight several factors, including corruption and currency stability, where the risks are higher than for other regional issuers.

Vulnerability to political risk

As Nigeria demonstrates, in a region where democracy and stability are often lacking, political risk is a latent danger to investor safety.

Not one of the 2015 issuer group chalks up half the available points for political risk indicators. With repression, corruption, cronyism, high unemployment and poverty marring the political environment, social tensions often place an increased burden on fiscal spending.

Few of these countries showed any improvements to their political risk indicator scores last year. On the contrary, in most of them selected indicators were downgraded.

They include repatriation risks for Angola, Ghana and Uganda, and government stability in Tanzania. Political risk in Cameroon is still among the worst of any prospective bond issuer in 2015.

On macroeconomic risk, Angola’s bank stability, GNP-economic outlook and government finances have all taken a hit from the falling value of crude oil, nudging the sovereign down to a lowly 92nd out of 186 sovereigns in the global rankings, and to less than 1.5 points away from tier-five status – the lowest ECR category, which comprises sovereign credits at most risk of default.

Several of Africa’s likely issuers this year are already languishing in that group. They include Tanzania, Uganda and Cameroon, which were all downgraded by Euromoney’s African experts in the survey during 2014.

Ignoring the reality

Gadio believes that economic and political risk factors “rarely come into play among investors unless a serious risk of default is in prospect, as occurred in Côte d’Ivoire in 2011”. It is “more the exception than the rule”, he claims.

In any event Côte d’Ivoire and Rwanda were upgraded in 2014, partly because of stronger growth rates linked to the improvements in their respective regulatory environments in recent years, which are more efficient as a result of tackling red tape and lowering the costs of doing business.

Côte d’Ivoire’s issuance means it has racked up around a third of the region’s total bond stock and its improving score reinforces the impression of considerable variation in risk across the region.

However, Euromoney’s survey also reveals there are still concerns about both Côte d’Ivoire and Rwanda given their low scores for a range of economic indicators, such as bank stability and government finances, which makes it imperative to take the holistic view of investor risk the survey is designed for.

Other issuers in any event have been affected by currency depreciation risk linked to prospective monetary policy tightening in the US.

This will exacerbate dollar-denominated debt-servicing costs, especially now that liabilities are rising in the region and beginning to offset the gains from the Multilateral Debt Relief Initiative granted a decade ago to help sub-Saharan African nations reach their 2015 Millennium Development Goals.

This article was originally published by ECR. To find out more, register for a free trial at Euromoney Country Risk.