|

|

John HouricanBank of Cyprus |

|

Regularly hauled in front of committees of self-aggrandizing politicians for ritual public humiliation, constantly attacked and ridiculed in the mainstream media, assailed by regulators, defenestrated by increasingly impatient shareholders for under-delivering, bank CEOs across the world have had a pretty rough time of it since the financial crisis.

But these things are all relative.

“I remember the morning I discovered my car had been burnt out outside the house,” recalls John Hourican, soon to be ex-chief executive of Bank of Cyprus.

“I’ve had some close security, but I never wanted them to be overly obvious and get in the way,” he says, sounding like the quintessential unflappable British army officer. “I mean: they hadn’t attacked the house or anything. They had just burnt the car. It was a message: ‘People are angry’. I understood that.”

Hourican, of course, is not British, though he made his career at RBS, working in its leveraged finance unit, then untangling ABN Amro in the wake of the consortium takeover and finally running the whole investment banking division at RBS as it sought to retreat back to core strengths and find a new path to sustainable profitability. He is Irish. He is also a man with a sense of honour, who talks often about standing up for his people, defending them, demanding that they work hard and take responsibility but never asking them to do anything he wouldn’t do himself.

When the board of RBS wanted a senior banker to take the fall over Libor rigging, it was Hourican, who had no involvement in such wrong doing whatsoever, that did the decent thing.

Then, as if all those adventures had not been enough, in 2013 Hourican took on surely one of the toughest jobs in banking, to be chief executive of Bank of Cyprus in the wake of a severe financial crisis emanating from a broken banking system, and brought low by losses on Greek government bonds.

The ECB, the European Commission and the IMF had bailed Cyprus out to the tune of €10 billion in spring 2013, but at a heavy price that required the island state to sign a memorandum of understanding with the dreaded Troika. Cyprus became the first eurozone member to be subject to capital controls and – still uniquely in the sorry and growing litany of eurozone crises – had seen depositors of the country’s biggest bank bailed in to recapitalize it. Fully 47.5% of any deposit over €100,000 was taken and exchanged for equity in the Bank of Cyprus, a desperate and broken institution left gasping for air in a now shattered economy. That equity looked, if not totally worthless, then not far off.

| I came into a bank where assets representing more than half the balance sheet were non-performing and found that not only did it not have any work-out group, it didn’t even have a unit to contact borrowers going into arrears, or a collections department Euan Hamilton |

As so often happens, a crisis emanating from one devastating weakness – a concentration of exposure to the Greek sovereign in bonds written down as part of the banks’ so-called private-sector involvement in its larger neighbour’s own bailout in 2012 – had quickly revealed many others at Cypriot banks: an over-reliance on funding from overseas, mainly Russian depositors; some of questionable provenance; that had been recycled into injudicious over-lending to the Cypriot real estate sector in a headlong rush to grow assets in the aftermath of entry into the euro.

Bad loans at one stage made up over 55% of Bank of Cyprus’s balance sheet. Amid a population cynical about economic contraction and now hugely distrustful of the banks, defaulting to lenders became an easy option, even for those that could pay. The path ahead for Bank of Cyprus after the depositor bail-in in April 2013 looked gloomy and headed, probably sooner rather than later, straight back into insolvency.And on the asset side, the destruction of wealth following the bail in of depositors, collapsing property prices and rising unemployment in a sudden and severe recession led to a swift rise in non-performing loans in a country with weak legal protection of creditor rights, which hit banks spectacularly ill-equipped to deal with the problem. What’s more, the Bank of Cyprus had to absorb the smaller and weaker Cyprus Popular Bank (Laiki Bank), with which it had previously competed to be the biggest in the country, so doubling up concentrations of exposure to poorly analyzed problem credits.Capital controls had to be imposed because without them, the Cypriot banks would have been stripped of deposits. The Bank of Cyprus may have been recapitalized by a bail-in of depositors but that very approach naturally deprived it of what would normally have been the natural funding channel for any re-equitized national champion bank after a crisis. The Bank of Cyprus was left dependent on Emergency Liquidity Assistance funding. It was on life support.

“When Korn Ferry rang me about Bank of Cyprus, my first thought was: ‘No, thank you’,” Hourican tells Euromoney. He had taken a few months off after leaving RBS, been to the Masters at Augusta, taken the family on holiday to Thailand and now, in September 2013, was looking to return to work. This wasn’t what he had in mind, though.

|

“But they said: ‘Look, come to Cyprus, meet the board, see what you think’.”

After the crisis in March and April 2013, the bank was emerging from resolution with a new board keen to find the right CEO. Ideally, in an island economy where political and business leaders knew each other almost too well, the nation’s largest bank needed an outsider to run it who could stand apart from back-stairs influence and run it ruthlessly in the right way. Maybe the board figured a top-rated banker from Ireland would feel some connection with what had happened to Cyprus. Hourican did.

“I felt that these people had really been dealt a bad hand and that they needed some help,” he says. “When you look at the psychological damage from seizing peoples’ deposits – and remember Banco Espírito Santo last year was bailed out, it wasn’t bailed in – there is a feeling on the island that this was an experiment by the European authorities on a contained population, which, if it went wrong, would have limited contagion to the rest of the eurozone.

Hourican says: “When I was taking apart ABN Amro for the consortium and repairing the investment bank at RBS, one key lesson I learned is that it’s not just about lining people up and leading them in the right direction. Speed really matters too.” He rolled up his sleeves. “We went into battle on all fronts.”Hourican read through the draft strategic plan for recovery the board of Bank of Cyprus had asked McKinsey to draw up – which he describes as perfectly reasonable – and decided that the demoralized staff at Bank of Cyprus had probably had enough discussions and strategy papers and now needed to get down to work. “So when I went back a second time in October, they offered me the job there and then and I decided to take it, though I discussed it on the phone first with my family.” “But for the people of Cyprus I felt that this simply mustn’t go wrong. The country was in shock, demoralized. People’s savings had been wiped out. The money in the provident fund had been raided. Their safety net had been pulled away, just as they had fallen on hard times and needed it. And later at the bank we had to make people redundant and cut the pay of those who kept their jobs by 16%.

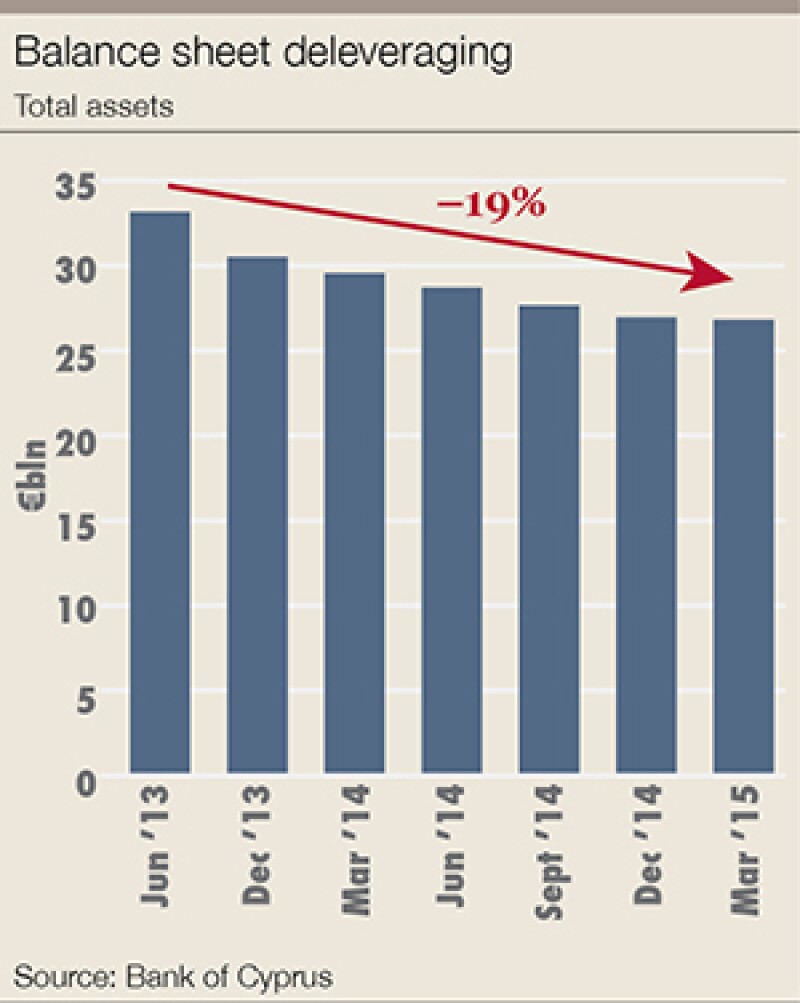

Buoyed by the arrival of such value investors, who no doubt scent better things ahead for Cyprus, shareholders who gained equity from the conversion of deposits were in no rush to sell when shares in the bank re-listed after 21 months of suspension. A remarkable turnaround story has unfolded at Bank of Cyprus over the past two years. The bank has rapidly de-levered the balance sheet ahead of schedule and by €1 billion per quarter, raising capital by selling off foreign assets and concentrating on its home market of Cyprus. It has also raised new equity capital from prominent international investors, such as Wilbur Ross, who now sits on an overhauled and much improved board that is chaired by Josef Ackermann, the latter is the former chief executive of Deutsche Bank and head of the Institute of International Finance who played a leading role representing banks on the haircuts they took on the Greece bailout in 2012.

The bank, while it has worked hard to restructure non-performing loans and so sometimes come into conflict with borrowers, has also worked hard to regain the trust of investors and depositors. It has reduced dependence on ELA funding from €11.4 billion at the worst point in April 2013 to €5.9 billion now. The bank even turned a small profit in 2014 of €31 million, before restructuring costs, discontinued operations and net profit on disposal of non-core assets: a return to profitability that comes after a loss of €359 million for 2013.

When I was taking apart ABN Amro for the consortium and repairing the investment bank at RBS, one key lesson I learned is that it’s not just about lining people up and leading them in the right direction. Speed really matters too. We went into battle on all fronts John Hourican |

That €1 billion share capital increase in July 2014 lead to Bank of Cyprus becoming one of the best-capitalized banks in Europe, with a common equity tier 1 ratio (fully loaded) of 14.9%. The capital increase, done via a private placing of new shares, represented the single biggest foreign direct investment into Cyprus in the country’s history. It was the equivalent of 6% of Cyprus’s GDP.

The placing attracted sophisticated investors from Europe, the United States and Russia, including as well as US billionaire Wilbur Ross, the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development and Viktor Vekselberg’s Renova Group, to which Josef Ackermann provides advice.

That capital raising, coupled with de-leveraging efforts, helped the Bank of Cyprus pass the comprehensive assessment and stress test by the ECB at the end of 2014. This hadn’t looked a likely outcome at the start of the year, leading to very intense discussions with the ECB. It would have been a small humiliation for the ECB if the poster child for its bail-in experiment promptly failed. It would have been a much worse disaster for Bank of Cyprus and for the country.

It’s quite a story of turnaround and redemption, and one that banks in Greece might cast envious and hopeful eyes over. It’s probably important not to declare victory too early, though. The bank still has a very high level of non-performing loans. But where there was only despair, now there is hope. And it’s almost hard to think back to how bad things were just two years ago.Instead, confidence has slowly returned. As controls that had restricted overseas depositors from moving their money have been lifted, most of those deposits have stayed at Bank of Cyprus. New deposit flows even turned positive in the fourth quarter of 2014 and through the first months of 2015, just as the crisis returned to Greece with a vengeance.

It is easily overlooked that behind all the other challenges that beset Bank of Cyprus in 2013, it had also been forced into a merger with its biggest rival, Laiki Bank, one with which its own ATMs could not even communicate.

So with the natural funding base closed off and problem loans escalating, there were a lot of other existential issues that needed attending to all at the same time. Observers freely praise Hourican for his energy and leadership qualities going into the fight. It also needed someone who knew the banking business inside out and was confident he knew exactly what he was doing.

|

And there was also another team that Hourican knew exactly the right man to put in charge of. “We broke the problems into pieces and gave specific responsibility for separate pieces to particular people and their teams,” says Hourican, sounding very much in battlefield commander mode. “So there was one team to take control of selling down the overseas assets, one managing the IT integration with Laiki, another concentrating on funding and liquidity, one dealing with regulators, another co-coordinating with representatives of the Troika and then a team reviewing the whole organization stack of the Bank of Cyprus.”

Ten years older than Hourican, Euan Hamilton had worked man and boy at RBS, leaving school to join the Scottish bank and carving out a career that saw him running the leveraged finance unit of RBS from New York while a young John Hourican ran Europe for him. Later they swapped seniority ranking and Hourican, now running the whole investment bank of RBS and so Hamilton’s boss, put Hamilton in charge of running down its non-core assets, a crucial job in restoring the bailed-out British lender.

Hourican didn’t go through recruiters Korn Ferry. He got on the phone to Scotland himself.

“I had essentially retired and taken to playing golf and walking the dogs at home, enjoying a quiet pint,” says Hamilton, who later lets slip that he was also running his own private equity fund, though not perhaps in the wholeheartedly committed way that he had worked at RBS.

His first reaction to the job offer was the same polite thanks but no thanks that Hourican had given to the headhunters. “But you know what a silver-tongued charmer John is,” says Hamilton [You can imagine the younger Irishman and the Scot chortling into their pints at this appearing in print]. “So when John said: ‘Just come down to Cyprus for three months and give me some advice’, I agreed. And now look at me, still here two years later working in 40-degree heat.”

Getting Hamilton to focus on the biggest challenge of all for Bank of Cyprus, coping with its sudden and potentially devastating increase in non-performing loans as director of restructuring and recoveries, was a crucial step in Hourican’s efforts to turn the bank around. “I enjoy working with John,” Hamilton says. “He’s very clever, very focused and very direct, with a clear strategic vision as well as a capacity to focus on the micro details. We dovetail well. I joke with him that he is the brains of the operation and I am the brawn.”

|

Hamilton adds: “John also has quite incredible energy. He’s like one of those Duracell bunnies that just never stops. It can almost be intimidating, but instructive also, I think, for some of the people at Bank of Cyprus to see him work all through the night, work all weekend if needs be. There was a cultural issue at Bank of Cyprus. It had been a bureaucratic and hierarchical organization, where bright young people became order takers. People tended to refer decisions upwards whenever they could. One of the most important things I hope we have both done is teach a young generation of bankers at Bank of Cyprus, who will lead it when we are both gone, that it is not a crime to take a decision and, as long as you can articulate sensible reasons for why you took it, not even if that decision turns out to have been wrong.

“I have seen people here at this bank grow up very fast in the last two years.”

There was a lot going wrong at Bank of Cyprus when Hourican and Hamilton arrived, in terms of loans going sour, and precious little being done about it. Following the Laiki merger, it turned out the now combined banks had extended loans running into the low hundreds of millions of euros to borrowers that were family-owned businesses that had over-extended into property.

Hamilton went to work. “I came into a bank where assets representing more than half the balance sheet were non-performing and found that not only did it not have any work-out group, it didn’t even have a unit to contact borrowers going into arrears, or a collections department.”

He built a 500-person team to chase borrowers who had missed payments, to try and restructure loans in a sustainable way and, where it seemed sound borrowers had chosen to default strategically, to attempt to enforce claims against collateral, a vexed process in Cyprus that led to a prolonged political battle to enact a new insolvency regime into law.

Hamilton also split his own group into teams: one dealing with retail borrowers, one with SMEs, another with corporations for whom standardized approaches could be made to work. It amounted in some cases to steps as simple as setting up call centres to contact borrowers that had missed a payments and initiate discussions on how to get borrowers back on track. Bank of Cyprus didn’t have one of these. It now has four such call centres. There were specific campaigns to deal with retail borrowers that had taken out Swiss franc mortgages and with holiday homeowners who had seen the value of their properties suddenly fall.

Hamilton says: “The bank had never paid much attention to keeping in contact with these borrowers. But we had to, or risk never hearing from the again, and find ways to restructure loans such that these borrowers could keep these properties. After all, we didn’t want to own them.”

| Harris Georgiades has been a very steady hand through all this, making sure that Cyprus meets the Troika programme or even beats the Troika schedule, lest the country suffer further erosion of confidence John Hourican |

Meanwhile an elite group within the 500 team of some 40 mainly local bankers, helped by 10 workout specialists brought in from KPMG’s restructuring team in London headed by partner Nick Smith, went to work on bespoke restructuring solutions for the 30 or so biggest problem borrowers that in aggregate accounted for roughly 50% of the bank’s €11 billion or more of NPLs, or roughly €5.5 billion. Each had a €100 million or more loan outstanding, some more than €300 million.

Euromoney asks for examples of a restructuring from among this top 30 group of borrowers that has gone well and one that hasn’t. Hamilton turns to the hotel sector.

“Aphrodite Hills Hotel was a seriously over-geared business that we ended up taking a 75% stake in for a nominal sum to avoid it going into foreclosure. It was then restructured and sold to a group of international property and leisure specialists, although that still awaits final approval from the competition commission. This was a proper, professional restructuring where we took something over, fixed it and brought in new money, attracting FDI into the island, which is absolutely crucial. Now I believe that, with the assets being properly maintained managed and nurtured, it will go on to better things and we can lend to the new owners to support that business.” Hamilton declines to be drawn on the extent of write-offs Bank of Cyprus took on the original loans only saying that the haircut was below the provisioning levels the bank had taken.

|

|

Harris Georgiades |

He contrasts it with another hotel group, which he can’t bring himself to name but one call to Cyprus confirms is the Aqua Sol Group. “This is a large hotel chain which we put into receivership where, because of the prior actions of the owners, it has been difficult to establish control and we look likely to be mired in court cases for a number of years. In the UK, it would have been neatly done and tied up by now. But in a country where the courts can be slow and unpredictable, it will not help anyone if the hotels don’t get the attention they need and customers notice and fall away.”

He adds: “One of the key topics I have most often discussed with the board is the need to restore confidence both in the Bank of Cyprus and in the country of Cyprus because without it, both would be lost.”But this nettle had to be grasped. Hourican says of how the Bank of Cyprus ran into collapse from the lending spree it went on between 2006 and 2013: “It was a lot of bad lending into bad law. When you look at the loan files, the people making those loans were clearly in love with collateral. But seizing collateral is very much the final step. You lend against cash flows. However when those cash flows aren’t there and you can’t get your hands on the collateral either, then that needs to change or the national banking system remains structurally unstable.” Cyprus deserves credit, which it doesn’t often get, for sticking with its Troika programme, even the deeply worrying parts. It can’t have been easy to push through laws seeming to protect banks in a country where people who had leant money to the banks in the form of deposits had lost part of their savings.A requirement of the Troika has been for the enactment of new legal protections for lenders to insolvent borrowers, and these are now just coming into effect. “It has taken a year and a half, which is a lot longer than it should have done,” observes John Hourican, whose time as chief executive has in part been taken up in intense, behind-the-scenes discussions over the new insolvency regime.

|

Bad loans still remain eye-wateringly high at Bank of Cyprus, even after two years of intense work to turn the institution around. Reducing them remains the single most glaringly important piece of work left to do. Bank of Cyprus will certainly resort to the contentious and begrudgingly passed new laws.

Euan Hamilton says: “Recent legislative changes around foreclosure and insolvency are complex and ultimately will require testing through action by us. However overall, while the changes are not perfect, we view them as a step forward for the banks and they will enhance the options available to us in driving forward settlements and restructurings. The bank has always been committed not to go for any form of mass foreclosure process, however we will use the full force of the new laws where appropriate, and particularly where we consider strategic defaulters are involved.”

Taking over as head of global banking and markets in 2009 at RBS, John Hourican had headed a division accounting for £124 billion of risk-weighted assets, which translates to €177 billion at current exchange rates.

When he arrived at Bank if Cyprus it had balance sheet assets of €33 billion, now down to €26.7 billion at the end of the first quarter of 2015, after a deleveraging of close to €1 billion per quarter, or 6% of the country’s GDP, over six successive quarters. It is a much smaller operation than the investment banking division he once ran, but being chief executive of a national champion bank in a nation going through its own Troika-led programme is a very different challenge to running a big division.

It has involved repeated M&A transactions, notably the merger with Laiki, but also a string of disposals of international operations that previous executives had built up. Hourican memorably describes these as the “misadventures of managerial international tourism”.

| Accepting the offer to chair the Bank of Cyprus’ board felt right. It presented an opportunity to continue my former engagement to help solve the problems facing the region and, as a consequence, also Europe as a whole Josef Ackermann |

Under Hourican, Bank of Cyprus has sold off assets in Ukraine, Serbia, and Romania. Just last month, Bank of Cyprus sold its most problematic holding, its 80% stake in Uniastrum Bank in Russia, to Artyom Avetisyan, the majority shareholder in Bank Regional Credit. The sale, at a small loss given the extent of write-downs, removes €700 million of RWAs and boosts CET1 capital, which stood at 13.9% at the end of March 2015, by 30 basis points up to 14.2%. While the bank retains rep offices in Moscow and St Petersburg, this latest retreat marks the last overseas banking subsidiary identified for sale and is quite a milestone.

“I’m afraid the Russian adventure will have been a rather expensive mistake by the previous executive team. Presumably it was based on some notion that because Bank of Cyprus had so many Russian depositors looking to preserve their wealth outside Russia, then we should benefit from having a bank inside Russia.” He shakes his head. He just doesn’t see it.

The Greek operations were surrendered in the 2013 bailout of Cyprus. So it now looks like the Troika did the country one big favour at least.

It’s been demanding work. “We sold our business in Ukraine, which had 500 staff mostly in Kiev, to Alpha Bank during the war there at a time when there were forces literally trying to steal that bank out from under us,” Hourican says. “I would like to keep the UK business, which serves a substantial immigrant community in north London that arrived after the 1974 crisis. But it is important to retrench from most of the other overseas expansion and concentrate on the market we know best.”

Bank of Cyprus has concentrated its remaining capital, funding and management resources on its home market and gone all in.

Another new experience for Hourican as a chief executive has been dealing closely and regularly with political leaders. It’s now clear Bank of Cyprus needed an outsider in the autumn of 2013, above the fray of interconnected friends and family in the beleaguered economy. He undertook from the start not to receive meetings requested by the rich and powerful of the country lest he be seen as open to influence. But he seems to have come to an accommodation with the finance minister. “Harris Georgiades has been a very steady hand through all this, making sure that Cyprus meets the Troika programme or even beats the Troika schedule, lest the country suffer further erosion of confidence.”

| We have done all the preparatory work to make this a London-listed stock in future, though a decision has yet to be made by the board. A company with a €3.5 billion capital base should be trading on a liquid, index-driven exchange John Hourican |

Restoring confidence has been his mission. Hourican recounts the phased unfreezing of the €3 billion of restricted three-, six- and nine-month deposits still locked in the bank from certain Russians and Ukrainians who had been bailed in in 2013.

“We discussed this with the Troika,” Hourican says, before his mischief takes over. “Well actually we told them we were lifting the restrictions as we were lifting them on the first tranche. We discussed it afterwards. The Troika originally argued that it might have been more prudent to roll those deposits over. We argued that would have been imprudent because it would have suggested some lack of confidence. And as most of those deposits stayed with us I believe we were vindicated.”

Restoring confidence in the Bank of Cyprus and in the country has amounted to pretty much the same thing, so the interests of Hourican and the minister of finance have been well aligned. The leaders of the Bank of Cyprus have had to repair the bank in ways that didn’t further damage a fragile economy after an extraordinary bail in that removed trust in the banking system and constrained its ability to provide credit. The government had to repair its economy in ways that didn’t damage the bank whose balance sheet is bigger than the country’s nominal GDP.

Hourican takes the discussion back to the vexed question of non-performing loans. “Many of those top 30 borrowers that account for half the bank’s NPLs were big employers on the island. We couldn’t simply declare them insolvent, though we put one or two into receivership partly to send a message of intent: that we will be intolerant of bad behaviour by borrowers seeking strategic default because we are guardians of our depositors’ money. We had to address each one on its own terms and seek voluntary restructurings with their boards that preserved as much as possible for the bank and kept companies operating. There were some common themes: many were diverse conglomerates, a hotel chain also with a marina, perhaps running a dairy, and operating some other real estate assets. Each one tended to have a vanity project. So each of these borrowers might need a number of separate restructurings.”

|

After that early refusal to meet privately with influential figures from leading business families, Hourican has since opened up. “I’ve talked to in the region of 5,000 customers. Many of them appear to like that a non-Cypriot is coming to them and explaining what is going on at the bank in an objective way. I think a chief executive from the island might not have been trusted during this phase. But people are starting to believe that we are fixing the bank and even that we have their interests at heart.”

Hourican knows – back to the inter-dependence of bank and sovereign – that the other half of the bank’s alarming stock of NPLs, comprising loans to individuals and to SMEs, will only come right if the economy revives. Investing in Bank of Cyprus really is buying a warrant on the economy, and that’s exactly the investment pitch that won over the most remarkable external validation of the Bank of Cyprus turnaround.

With NPLs still high, the country still under a Troika programme and the ECB’s comprehensive assessment and stress tests looming in the second half of 2014, Hourican knew Bank of Cyprus had to take additional steps to bolster itself. “I had been in the job less than six months and could see that even with the deleveraging and NPL trades we had done we still needed more capital, and so I retained advisers from HSBC to help explore ways to raise it.”

It was another of many tricky moments of Hourican’s tenure as chief executive because it brought him into conflict with certain factions on the board of directors at Bank of Cyprus.

When the bank came out of insolvency in mid 2013, the new board comprised a number of directors who had taken seats following the bail-in of large Russian offshore depositors. While perfectly reasonable people, these were not banking experts who brought much value to the table in advising on strategy or the business of banking, and they had their own interests at heart. A certain grumbling hope for restitution of lost deposits still lingered. And, having been handed equity in the bank in such a fraught manner, they were disinclined to be diluted as the first glimmer of hope appeared that this stock might even turn out to be worth something one day.

Hourican recalls: “A significant contingent of the board tried to stall the equity raise, suggesting that the option to raise fresh capital would always be there. I said: ‘No. There is a window that’s open now and we need to go through it.’”

Hourican shared his plans for more capital raising with the government and local regulators and, backed by their support, strong-armed the idea of the equity-raise through the board.

In the middle of 2014, as part of the so-called project Chronos, an HSBC team led by Tim Sykes and John Crompton introduced Hourican to 100 prospective investors, including many strategic value investors looking to buy turnaround stories. Hourican wanted to raise €1 billion.

Hourican says: “You’re pitching at 0.4 times or 0.5 times tangible book value and the first challenge is getting that back to 1.0 times. So this is not selling some sunny uplands story of growth, even though we do think the bank will eventually earn a decent return on equity, generate surplus capital and pay dividends. But we had to go in detail through the whole story of dependence on ELA funding, fixing the NPL problem. We also pitched the story of good management of the bank, good government policy and the bank as a warrant on the Cypriot recovery. We were able to convince close to 40% of those 100 investors we met.”

One stood out.

Wilbur Ross, the US billionaire who has invested in numerous failing banks bought from the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation across the US and turned them around, had invested in Bank of Ireland, made good returns and exited, and was now looking for a new chance to put a large amount of money to work and secure a big stake in a European bank turnaround story. He subscribed €400 million of the total €1 billion raised, took a board seat, became vice-chairman and subsequently worked to enhance governance of the bank in ways that resolved tensions between Hourican and certain factions on the board… by removing them.

Ross is fascinating to talk to partly because he takes such a calm, considered, direct view of the basics. He also shows how Hourican had a slice of luck.

| The Bank of Cyprus has been operating in the black, continuously adding to provisions against NPLs and building their resilience to stress tests. That turn around to operating in the black has come much faster at Bank of Cyprus than it did at Bank of Ireland Wilbur Ross |

Ross tells Euromoney: “The first piece of analysis we had to do was on whether Cyprus was a place we wanted to be. We decided ‘Yes’ for a number of reasons. It surprises people to learn that its population is the best educated of any OECD country as measured by the percentage of college graduates. That is reflected in the big industries in the country, which, as well as tourism, also include various corporate and professional services: accounting services, ship management and the like. It is not just its tax treaties with other countries that sustain the economy, though at the time we went in Cyprus had treaties with 23 countries and now has with 28 countries. So partly on the back of those we saw a good long-term outlook for the business services part of the economy.”

And Ross saw two other areas that gave him hope that he might be picking up for €400 million an inexpensive warrant on an economy with a bright future: the potential for lots of growth in tourism; and the recent discovery of natural gas off shore which, subsequent to his investment, Mobil has declared to be commercially viable.

Ross says: “With a large RAF base and US electronic surveillance stations, Cyprus is entirely safe and stable while being close to an unsettled part of the world. Recently it has attracted more tourists from the UK and Germany to replace declining numbers from Russia and the Ukraine, but there is also the clear potential to attract visitors from countries such as Bahrain and Egypt. Right now, the tourist season is short, from May to September, but this is an island with many interesting sights from centuries of occupation by various powers, as well as excellent topography with good beaches and restaurants and even snow in the mountains. It can do much more with tourism, if the government gets on with the task of reducing landing charges to encourage more low-cost carriers.”

Sources at the Bank of Cyprus suggest the island could double the 2 million visitors who arrive each year. Ross says: “We have spoken to Ryanair and they could be part of bringing in another 2 million visitors annually. Even If they each spend as little as €500, that is another €1 billion a year potentially coming into a small economy.”

Ross sees a new determination in the government following the financial assistance programme, depositor bail-in and recession, to now maximize its resources. “The government has decided on privatization of the airports and the sea ports, which have been inefficiently run under public ownership with high charges. Those should come down, and all that will benefit tourism.”

The natural gas discovery is the real kicker, though. “Power and electricity costs have been very high in Cyprus, and they will come down,” says Ross, “benefiting the whole economy. It will also export natural gas. Egypt, for example, has already said that it will import it. If anything like the estimates of how many billions of dollars of oil equivalent do turn out to be commercially viable, then that could be a real ‘wow’ factor for Cyprus. We might be talking per capita GDP levels similar to the UAE. It could be quite transformational.”

Ross is wonderfully matter of fact. “So there’s a good long-term macro story,” he concludes.

“At the micro level, it’s all about properly restructuring the NPLs and then, after a couple more years of that, what profits the bank might produce. Partly that’s a function of the economy and possibly of competition. We like the fact that Bank of Cyprus on its own is one third of the banking system. And banking in Cyprus has been quite high margin.”

Wilbur Ross |

Ross says he sought assurances from the president, the finance minister and even the political opposition in Cyprus that the new insolvency and foreclosure regime required by the Troika would indeed pass into law. It’s a signal of how important his validation – as part of the biggest-ever single FDI in Cyprus – is for the country as well as for the bank that they provided it, even if the process took longer than he expected. Ross thinks that with the primary legislation passed, the NPL problem will be resolved because so much of it is secured against property collateral. “The economy is turning around and I think that recovery is going to accelerate. That will be a factor in reducing NPLs and also supporting property values. They’re not going to be building any more beach front.”

Ross, of course, also did his due diligence on the Bank of Cyprus management team. Although he had not met Hourican, he was able to check his and Euan Hamilton’s credentials with old contacts from RBS, including Jayne-Ann Ghardia, chief executive of Virgin Money in which Ross has remained invested ever since backing Richard Branson’s bid to acquire Northern Rock after the UK’s own financial crisis. Ghardia spent five years at RBS running a big mortgage book. “We absolutely believed that these were the right people to lead a fundamental clean up of this organization,” says Ross.

He sees promising signs. “The Bank of Cyprus has been operating in the black, continuously adding to provisions against NPLs and building their resilience to stress tests.” He sees the situation in Cyprus as having some comparison with Ireland. “That turn around to operating in the black has come much faster at Bank of Cyprus than it did at Bank of Ireland,” he notes.

Confidence is returning. “To my knowledge there has never been another event in a developed economy like the bail-in of depositors in Cyprus. And we did worry about a possible loss of ex-patriot deposits after restrictions were lifted,” says Ross. “There is another wholly owned Russian bank on the island and we wondered if deposits might migrate there. But in fact they did not, and we have even been attracting more Russian and Ukrainian deposits.”

Ross joined the board of Bank of Cyprus as vice-chairman and sounds pleased to be doing this, after so many successful bank turnarounds in the US. “Such are the regulatory restrictions on private equity funds investing in banks in the US that not only am I prevented from acting as an officer or committee chairman, I can’t even deposit more than $500,000 of my own money at a bank we own.”

Ross notes drily: “In Europe they seem more open to the idea of having people on the board of a bank that might possibly have something useful to offer.”

He says: “It’s been pleasing to be able to bring insights from previous investment. We did, for example, previously own a very large mortgage loan collection business in the US and so we know that business well.”

Ross played a key role in bringing Josef Ackermann in as chairman of Bank of Cyprus and then helped him to overhaul the board. “The people on the board when we invested I found to be earnest and hard working and given to lots of long meetings. They certainly weren’t attempting anything improper. But they didn’t know a lot about banking, and a lot of board time was taken up going over the basic ones and twos of the business. It seemed inappropriate, given their now small stakes, that they should dominate the board rather than people who could offer strong counsel and judgment, and its composition changed, with the EBRD also coming onto the board.”

Hourican was delighted by how the equity raise brought the capital needed to pass the ECB stress tests, demonstrated sophisticated investors’ validation of the strategy to deleverage by selling international operations and concentrate on Cyprus and also solved at a stroke his problems with the board. Probably the biggest validation came from having a former chief executive of Deutsche Bank and former chairman of the IIF become chairman of Bank of Cyprus.

It’s a job Ackermann takes very seriously. He spends at least one week a month in Cyprus. In his new role he has, of course, met the president of the republic and the minister of finance of Cyprus, as well as the central bank governor and other senior officials and political leaders, as well as Troika officials. He has hosted client events.

Ackermann’s arrival curiously brings the tale full circle. At a time when Cyprus seemed to want outsiders rather than islanders to take charge of the country’s largest bank, suddenly it found a flood of them. Ackermann has been a director of Zurich-based Renova Management, part of the business of Viktor Vekselberg, the second-richest man in Russia. Renova had invested alongside Wilbur Ross and the EBRD in the €1 billion share placement that was also supported by 30 other large investors, making the potential beginning of a future institutional following for the Bank of Cyprus stock.

|

Hourican jumped at the chance to get such a figure onto the board. Ackermann, who has resisted previous interview requests on his time at Bank of Cyprus, tells Euromoney: “I readily accepted this offer because of my Greek connection, so to speak. Not only did I study classic Greek in high school, but I have since my youth visited Greece many times and made many Greek and also Cypriot friends. As CEO of Deutsche Bank and chairman of the board of the IIF until 2012, I was deeply involved in official discussions with the Greek and European authorities on a solution to Greece’s economic crisis and the restructuring of its public debt in particular.

“In this context, I have followed very closely the economic developments in neighbouring Cyprus and the difficult challenges the Cypriot authorities and the Cypriot banks had to face, partly as a consequence of developments in Greece. Accepting the offer to chair the Bank of Cyprus’ board felt right. It presented an opportunity to continue my former engagement to help solve the problems facing the region and, as a consequence, also Europe as a whole.”

He still took a considered view of what had happened to the bank from the crisis in 2013 to the middle of 2014. “In addition, it reflected my perception that, despite the difficult – if not exceptional – challenges, the bank was solvent and had adopted an appropriate medium-term strategy, with a brighter outlook over the medium term for the restoration of full financial health and the delivery of shareholder value, while also contributing to the recovery of the Cypriot economy and playing its traditional role as the largest banking and financial services group in Cyprus.”

Ackermann did not know John Hourican before joining the Bank of Cyprus. So what is his assessment of Euromoney’s banker of the year for 2015?

Ackermann says: “Very quickly I have come to observe, benefit from and appreciate his great talents and excellent technical, managerial and communication skills.” It is perhaps no surprise that he approves our choice. “In a nutshell, he has, in a short period of time, instilled self-confidence and motivated a rather discouraged staff, established rigorous and effective management structures, empowered a team of talented young executives to respond to the new challenges and implemented a demanding restructuring plan, establishing a new, dedicated loan restructuring and recovery division – an internal bad bank, if you like. He also secured a very successful and very timely recapitalization of the bank from foreign investors, made major strides in deleveraging non-core assets in other countries and sharpened the focus of the bank’s core activities in Cyprus.”

Ackermann is encouraged not only by the recent growth of deposits but also by a modest pick up in loan demand from creditworthy borrowers. He suggests lessons have been learned on the front book of new loans from the restructuring of poorly extended old ones. “I can assure you that the strategies we have followed seek to achieve a sustainable outcome for the borrower, better protection for the bank and, importantly, better lending standards across the portfolio.”

As well as continuing efforts to work down NPLs, Ackermann identifies other priorities. He says: “Diversification of the bank’s funding sources, enhancing operational efficiency and considering the potential listing of the bank on a more liquid, index-driven international stock exchange are just a few of the other areas we continue to focus on.”

Ackermann has another important task too: finding a new chief executive.

Hourican talks enthusiastically about the potential to build on the capital raising of 2014 and to list the Bank of Cyprus stock on a larger exchange where it might benefit from index inclusion. The local exchange in Cyprus is quite illiquid, while trading in Athens has been suspended. If the bank turnaround continues and the economy recovers as hoped, the stock will be almost too big for these local venues. It will be the equivalent of a FTSE250 company, but trading on AIM.

Hourican says: “We have done all the preparatory work to make this a London-listed stock in future, though a decision has yet to be made by the board. A company with a €3.5 billion capital base should be trading on a liquid, index-driven exchange.” When the bank finally frees itself from dependence on ELA funding, the prevention on paying dividends will lift. That might be an appropriate moment. With Cyprus soon to get out from under its memorandum of understanding, Hourican hopes this plan can progress rapidly.

He won’t be in the chief executive’s chair to see it, however.

Hourican disclosed to the board earlier this year that, with his wife and family back in Ireland, he could not commit to staying in Cyprus beyond the end of 2015. Given that the core foundations for recovery were in place, the Cyprus economy was showing signs of early recovery and the bank needed a stable in situ leadership team to pursue its listing ambitions Hourican decided it best to serve notice of his intention to resign. This, of necessity, led to regulatory disclosures and an agreed date for Hourican’s time at the bank to come to a conclusion, probably during September or October of 2015, depending on the transition to his successor.

Euan Hamilton says he will be around for as long as he feels there is still a need for him to provide support for the bank’s restructuring efforts, which are now well underway. Ross, as an investor, doesn’t commit to timelines or price targets but is clearly in for the long haul.

Ackermann, too, remains committed. He tells Euromoney: “I have no plans for an early departure from these challenging and rewarding duties”.

He continues to search for a new CEO. “We simply want to hire the best candidate possible. We are seeking someone of international stature with strong technical and leadership skills, who will make a real commitment to working in Cyprus. Success of the bank goes hand and hand with the success of the Cypriot economy. We need to work together with all stakeholders to attain our shared objectives.”

For Hourican, still just 45, it has been an extraordinary two years in which he has proved his capabilities and experienced as a CEO all the challenges and thrills of working closely with government, regulators, a changing board of directors, leading a vitally important capital raising as well completing M&A, all in extraordinary circumstances. He has delivered. He has shown leadership as well as technical competence, and he talks warmly about those he now leaves behind.

“There was no lack of intelligence or competence among the bank’s staff. In fact, as time passed I have grown increasingly impressed with the quality of the people at the Bank of Cyprus. As well as a world-class board, it has a great executive team. Everyone has got behind the programme. The people needed leadership. They needed someone to stand in front of them, to defend them and give them room to do their job.”

It’s a shame, perhaps, that no one stood in front of Hourican at RBS.

Euromoney expects to be talking to him again before long. He’s unlikely to be short of work offers. It’ll be a tough ask to take a next job more challenging than his last, though.