|

Robo-advisers, automated online or mobile investment advisory services, will eat as much as $90 billion of traditional adviser revenues by 2020, according to management consulting firm AT Kearney.

A study conducted by the firm in May showed that 3% of banked customers already use a robo-advisory platform. Of the 4,000 US consumers surveyed, almost half said that they had some interest and 70% of those said they might use robo-advisers to manage their household table investments.

The move to robo-advisory platforms is well under way in the US and most of the providers are new entrants. FutureAdvisor, Wealthfront and Betterment are Silicon Valley-born companies who have joined Charles Schwab and Vanguard in offering low-fee automated wealth management to clients that have not been able to access advice typically reserved for the wealthy.

That will put pressure on the big banks and brokerages that have wealth management arms, as well as smaller registered investment advisory firms.

“It has been the classic disruption and the democratization of advice,” says Uday Singh, a partner in the financial institutions practice at AT Kearney. “Silicon Valley has taken existing technologies to the next level. They saw it was priced generously at 1% for advice so waved their magic wand and dropped that to 25bp and opened up services to a whole new customer base.”

That predominant customer base is under 35 years old with money to invest, and enough financial knowledge to work with a robo-adviser and know to not trust a bank. “It’s come to the point where the younger American investor would rather trust a robot than a financial adviser,” says one retail banker.

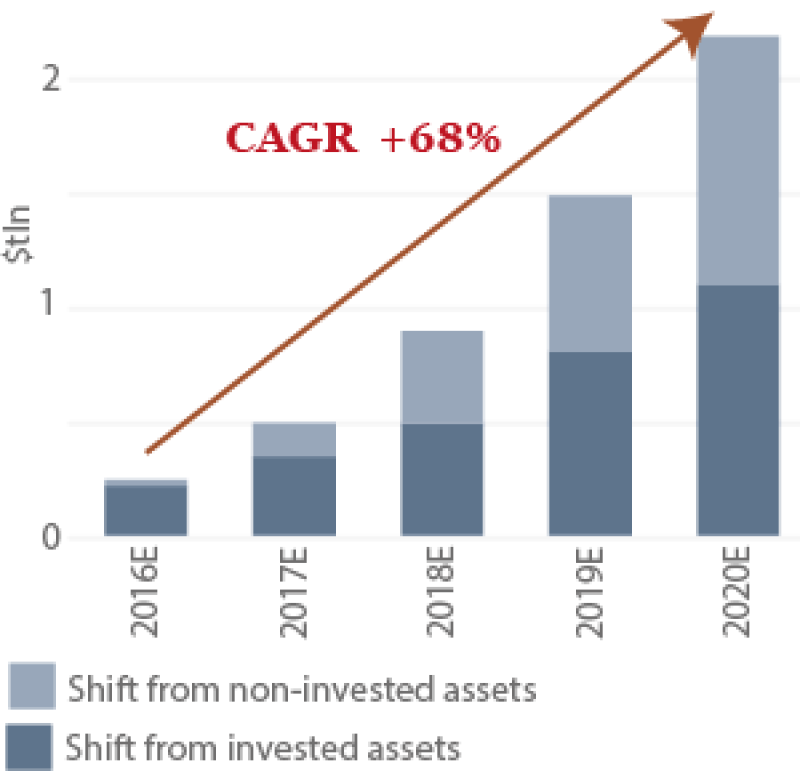

Singh believes robo-advisory will become mainstream over the next three to five years. Indeed AT Kearney’s report estimates that while 0.5% in investable assets are invested using robo-advisers now, by 2018 that will be 2.7% and by 2020 as much as 5.6% – more than $2 trillion.

|

Banks will come up with a product or service to compete Rebecca Lynn, Canvas Venture Fund |

Analysts at Citi studied the robo-advisory market in their disruptive innovations study published in July and concluded that from a $19 billion market at the end of 2014, it could grow even bigger than AT Kearney’s estimate.

“Based on the distribution of younger individuals within the population, and the net investable wealth those individuals hold, we estimate the target addressable market for robo-advisors could be $1 to $5 trillion over the next 5 to 10 years, “Citi predicts.

AT Kearney’s study points to ETF growth as an example of how unfamiliar products can take market share in a short period of time. In 1999 ETFs accounted for 0.2% of US investable assets. By 2013 that was 4.9%. Given that digitization and information flow is far more advanced now, the firm says the growth rate of robo-advisers is likely to be much faster than that of ETFs.

What does it mean for traditional advisers? Revenues will drop across the whole industry due to pricing pressure, says Singh, and traditional advisers will start to see a $1 billion revenue fall as early as next year, and a $3 billion drop in 2017.

Price war

After that will depend on whether the players enter a price war – a case Singh believes likely. Without a price war, losses to baseline revenues are estimated to be between $8 billion and $12 billion by 2020, but if a price war ensues that loss could be as much as $90 billion.

Martin Moeller, who works in digital private banking strategy at Credit Suisse, says that the US brokerage model is under pressure to change. “US banks need to adapt to capture future revenues in new ways,” he says.

“The country has, up to now, been dominated by a brokerage model and that needs to change. The clients are evolving, they are more financially skilled, less trustful and more involved in the financial decision-making. Where banks don’t deliver the new kind of banking they seek, robo-advisory increasingly fills the gap in the market, especially in the retail and affluent segment.”

Singh says while the non-traditional players like FutureAdvisor are gaining ground, they face fierce competition from regional banks. “While revenues will fall at traditional advisers there is a big opportunity here,” he says. The regional banks in the US that do not advise the mass affluent could add a new revenue stream.

“The regional banks that already have the client base could easily tie up with a tech firm for a white-label robo-advisory platform,” says Singh.

Rebecca Lynn, co-founder and general partner at Canvas Venture Fund, is not so sure. She led FutureAdvisor’s Series B funding and sits on the board of peer-to-peer lender Lending Cub. “The US consumer is not enamored with US banks right now, so the question is will they want their wealth management from them or an independent player?” she says.

“Our bet is that the banks will come up with a product or service to compete with the standalone robo-advisers but that they will struggle with the consumer sentiment against them.”

Estimated US robo-advisers AUM ($trn) |

|

Source: AT Kearney simulation model |

Traditional fund and brokerage houses like Vanguard and Schwab could also move in. Says Singh: “The traditional fund complexes have a strong distribution network – with strong brands, solid balance sheets and deep pockets for marketing. They also have the personnel to be able to backstop services with a human when needed.

“Given the low barriers to entry, it would be easy for someone already established to move into robo-advisory.”

How to adapt the business model will be the biggest challenge for any traditional financial firm looking to expand into robo-advisory.

Singh says it will likely lead to unbundling of services. “If banks can no longer charge 1% but still have the cost of the human adviser then they will likely have to unbundle services and charge different prices. While the model used to be sales-driven with branches and adviser/customer conversations, it will be an internet-only experience.

“And it will also have to be in real time and that will require a whole new way of dealing with clients across the board. A client won’t accept a real-time experience in wealth management but not in banking.”

He adds that the European banks are in a better position than US banks as disruption in Europe has yet to occur. “They would do well to get ahead of the disruption,” he says.