|

Zurich Insurance Group is one of the most powerful asset managers in the world. It has more than $200 billion under management. It also has a clear commitment to invest its assets in ways that, in its own words: ‘Do well and do good’.

So when Manuel Lewin, head of responsible investment at Zurich Insurance, speaks about the developments he wants to see in the so-called green bond market, issuers and intermediaries should take note.

“What hasn’t sunk in with the broader potential issuer base is that in the end the advantages of issuing a green bond go way beyond the diversification of the investor base or hopes of an effect on pricing,” Lewin says. “Issuing a green bond is a signal to the market that here is a company that thinks about risks related to climate change and to other environmental challenges and has a plan for how to tackle them by making investments to address them. This could and should affect the broader assessment of the credit risk of that issuer.”

Chris Wigley is a senior portfolio manager at responsible investment fund Mirova, which launched a specific green bond fund that now manages €64 million. He sees “tremendous” potential in the corporate market and recognises the benefits for the companies involved.

|

“Recently we’ve had the G7 announce that they want to be fossil fuel free by the end of the century,” he says. “This type of change poses a risk to some corporates and they have to adapt. It’s a challenge for them and we think green bonds are part of the solution.” The views from these influential investors are clear, but they have rarely been heard in the debate about the future of the green bond market. Much of the discussion over the past few years has centred on the efforts of issuers and the banks that sell the securities to get the market off the ground. To its detractors, the green bond market has been as much about marketing as real substance.

But a Euromoney survey of close to 40 leading fixed income investors shows the true potential of the green bond market: that it has become, quicker than many think, a core part of global fixed income. And more importantly, that it can be a sustainable market in its own right, one driven by real demand rather than a desire to demonstrate sustainability credentials.

In the early days of the green bond market were dominated by supranational and agency issuers. But the Euromoney survey shows there is now a clear desire from investors to move on, and that a market for corporate green bonds needs to develop.

Why? First and foremost, the projects supported by such deals often relate to energy efficiency, and the outcomes of these projects are viewed as easily assessed. The second is an age-old investment requirement: corporate bonds are crucial for portfolio diversification.

“Corporate bonds generally provide more yield than supranational bonds, and though I am trying to support green, I have to be cognizant of our returns. Corporate green bonds offer a way to do that,” explains Cathy DiSalvo, an investment officer at the California State Teachers Employees’ Retirement System (CalSTRS), which has been a supporter of the green bond market since the $190 billion fund first bought a World Bank green bond in 2009.

|

The diversity on offer is twofold. Not only do the different issuer types – be it banks, manufacturers, industrial firms, energy companies or whatever – carry with them different credit qualities that can appeal to portfolio investment strategies, but there is also diversity in corporate green bond asset types that will appeal to varying investor sophistication. These include green high-yield bonds, green project bonds, green asset-backed bonds, green covered bonds and even green real estate investment trusts. “Europe is ahead in corporate green bonds, but the US is starting to come around. We want to see them being issued so we can buy them to diversify our portfolio. It’s a huge thing for us. We need a variety of credit ratings and some higher risk opportunities,” says Benjamin Bailey, senior fixed income investment manager at Everence Financial in the US.

“Actiam – as a major buyer of green bonds – is delighted with the market growth we’ve seen in recent years,” says Manuel Adamini, special adviser to Actiam, a Dutch responsible investment asset management firm. “It’s great that corporates have entered the space, but it is still dominated by sovereign and supranational agencies. For green to become the new ‘business as usual’, the corporate sector has to endorse it much more strongly, by deploying more green assets and by financing them green.”

Lewin at Zurich Insurance adds: “Corporate bonds are a large segment of the fixed income market. It would be nice to see a higher proportion of that being issued as green, something akin to what we have seen in the supranational space. Of all the different fixed income sectors, the corporate one has been disappointing in terms of the issuance we have seen.”

Dealogic figures show that over the 12 months to August 17, the top 50 corporate bond issuers issued debt worth over $1.8 trillion. Of these companies only one, Toyota, issued a green bond during that period. The asset-backed bond was closed by Toyota Financial Services in June. The deal totalled $1.25 billion, with proceeds going towards electric and hybrid car loans.

Green bonds: The facts |

Number of deals done year-on-year is up so far in 2015, to 58 from 54. • Average deal size is down by $100 million • Volume down 20% year-on-year to $17.3 billion at the beginning of August 2015 • SSA issuers account for the largest share of green bond volume in 2015 YTD with a 45% ($7.8 billion) market share • The euro is the leading currency in 2015 YTD, accounting for 41% ($7.1 billion) of green bond volume |

The main obstacle to corporate issuance relates to cost. Companies are also understandably reluctant to pursue a source of debt that will open them up to increased scrutiny and oversight.

“When corporate issuers visit us we always ask if they are planning to issue green bonds,” says DiSalvo. “Many seem interested but after researching the possibility, feel it is too expensive and labour intensive to do so.”

While green bonds are thus far only governed by voluntary guidelines, market expectations for information on the use of proceeds are high. Issuers must be very clear on what the outcome of the green project concerned will be and how they will measure the impact. And that comes at a price.

Many green bonds will come with a second-party opinion assessing the greenness of the project the financing will support and these documents are not cheap. Running into hundreds of thousands of dollars, this process can be beyond the reach of many issuers.

“The challenge is to have a set of clear rules that make it easy for corporate issuers,” says Sean Kidney, CEO of the London-based Climate Bonds Initiative. “At the moment there’s a lot of confusion about what they have to do to take advantage of the market, what is acceptably green and so on. That all suggests a high cost of transaction.”

His firm is working on a certification scheme to reduce those costs.

Of course cost is not a problem for all. There are many multinational corporates with deep pockets that could issue a green bond with documentation.

|

|

|

|

One reason for not doing so is that investors are looking beyond the green criteria of the bond before buying. They are also looking at assessments of the company’s wider environmental, social and governance (ESG) rating.

“We use MSCI for ESG ratings in our fund,” says Bailey. “We’ve been able to discuss the environmental or E score with some of these companies to make sure they understand that investors do care. We are glad they are coming to the green bond market but we want them to keep striving for more.”

This extra scrutiny can be off putting.

Respondents to the Euromoney survey said that of all the tools available in assessing the green credentials of the bonds issued, second-opinion reports were the most useful.

“We think second-party opinions are valuable, particularly to first-time issuers in green bonds because they may need guidance in what may be considered a green project or not. Similarly the second opinions can be helpful to new investors as well,” says Wigley at Mirova.

The market for providing these second opinions is booming, but there is a level of uncertainty about the quality of the reports arriving on investors’ desks.

One of the largest investors in green bonds to date, who spoke on condition of anonymity, recalls receiving multiple-paged reports containing only a few paragraphs of useful information.

Caroline Cruickshank is managing director in BNY Mellon’s Corporate Trust Strategy Group, which supports issuers as trustee and agent as they develop their bonds. She believes the second-opinion market needs longer to establish itself.

“We are seeing examples of issuers employing second-opinion providers, but it’s hard to say just yet whether this will assuage greenwash sceptics. We need to give it a little more time, we need to be able to really test and challenge the market until we can say this is robust or transparent enough,” she says.

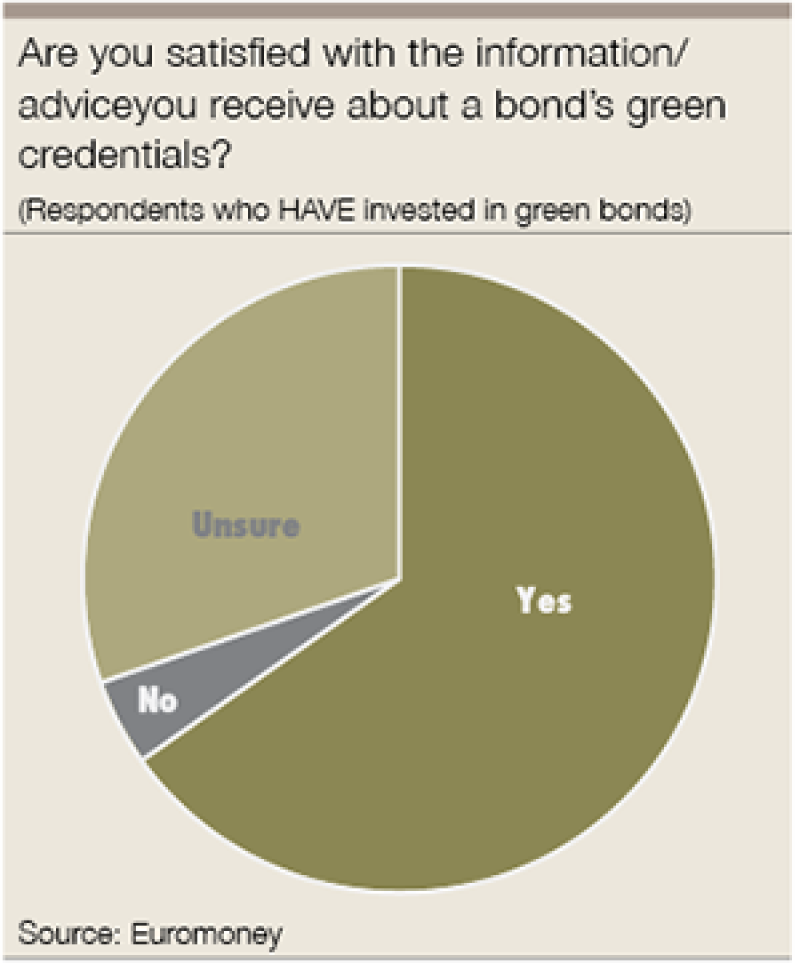

Investors already note an improvement in the quality of the reports being issued, with 65% of respondents to the survey saying they are happy with the information they receive. However, these reports are still not considered a solid stamp of approval by investors.

“With any normal corporate bond, an investor will not buy it [just] because a credit rating agency has rated it double-A,” says Wigley. “They need to do independent research as well. And it’s the same with ESG, it could be that the second party may approve of the programme or project, but it’s so important for investors to do their own research too. What is green for one investor may not be for another.”

Green Bond Survey findings |

Almost half of respondents made green bond investments without having a specific sustainability/green/ESG policy in place • The majority of investments (almost 70%) were in bonds issued to support renewable energy projects • Insurance portfolios and foundations topped the leader board in terms of the stakeholder groups showing most interest in green bonds, although demand was fairly evenly spread • High net-worth investors demonstrated the least interest in the sector • Second opinions issued with green bonds are heavily relied upon and broadly trusted by investors • Investors showed overwhelming support for the issuance of more corporate green bonds, with more than triple the demand for these over any other category asked about • For those who are already green bond investors, there was little concern about the lack of a firm definition of green for these bonds. Investors yet to enter the market showed a little more uncertainty. • Almost 60% of respondents would like to see mandatory rules introduced to govern the green bond market • In response to the growth in this market, over 30% of respondents have either launched or are planning to launch a specific green bond fund. For those yet to invest in green bonds, the main reason was not the lack of track record of the market but the lack of suitable investment opportunities |

The main challenge to the second-opinion reports, their producers and those reading them, is the question of what should be considered green in the first place. This problem has loomed over this market since the beginning.

Euromoney found that almost 60% of respondents would prefer not to see a firm definition of green imposed on the market.

“I would be nervous about setting a firm definition,” says Bailey. “I would rather have $250 billion of issuance in all shades of green rather than $50 billion of only dark green. The need for this financing to answer the call of climate change is huge so we don’t want to stunt the market by asking too much of issuers.”

Wigley agrees: “It would be a tragedy if a green bond came and was going to be financing very worthwhile projects but was deemed ineligible for investment because it didn’t comply with some small area [of a definition].”

He adds: “We believe this is a young, growing market, it needs to be innovative to meet the challenge of climate change. We think the Green Bond Principles provide the flexibility needed.”

Flexibility may be the requirement in the overall principles, but there’s one area in which investors want to see much clearer guidelines. Around 60% of respondents to the survey said they would welcome the introduction of “internationally agreed, mandatory rules”. It is evident from speaking to the investors individually that their desire in this area is focused on reporting.

Concerns over transparency and the accuracy of the information available from issuers about the results of the projects funded by green bonds are rife.

“There should be rules and guidelines surrounding reporting and what it should entail,” says DiSalvo. “The transparency of those who are currently reporting properly makes it possible to comprehend the projects involved in their various issues.”

“There definitely needs to be more clarity around impact reporting,” agrees Mike Faloon, chief operating officer at Standish, a fixed income subsidiary of BNY Mellon. “As we begin to manage these dedicated impact strategies we will need the correct reporting to be able to do that.”

This brings up the area in which investors have most concerns about the green bond market. They call it ‘greenwashing’, whereby an issuer labels a bond as green when the money may not be sufficiently ring-fenced to be used solely for green projects. Greenwashing is hindering development of the sector. A number of investors recall passing up potential opportunities to support seemingly worthwhile projects because they weren’t certain the financing would be used appropriately.

“There is a risk greenwashing could compromise the confidence in the market before it even gets going,” says Jason Milne, vice-president of corporate governance and responsible investment at RBC Global Asset Management in Canada, which is yet to invest in green bonds.

|

|

|

|

Before firm reporting rules are established, investors are doing their best to investigate and track the impacts their investments are having. The process is time-consuming. Snippets about the results of the projects can be found in various places on issuers’ websites, yet the information is often not routinely sent out to investors.

“There is certainly a healthy amount of digging to find the information we need to assess the impacts,” says Bailey.

Investors are not shy about questioning issuers if what they find does not please them, explaining the information is crucial to future investment decisions.

“I’ve bought a couple of the green Reits based strictly on the credit; the fact that they are green is the cherry on top,” says DiSalvo. “However, I have to be diligent about checking their reporting and achievements on an annual basis. If I find that their projects aren’t in line with my expectations or that their reporting is unclear, then I would consider passing on their future issues. I wouldn’t necessarily sell my current holdings but I might not buy them again and would approach the issuer to ask questions and provide feedback.”

Bailey says: “We have electronic files where we are keeping information on what the deals we’ve done have actually achieved. We haven’t been too disappointed with anything we’ve seen but we will continue to checkup and see that these issuers are doing what they should be doing. If they aren’t then we would need to have higher scrutiny the next time we look at their deals or we could possibly sell the deal if it was terribly egregious.”

Green Bond Principles |

The Green Bond Principles, updated in March 2015, are voluntary process guidelines that recommend transparency and disclosure and promote integrity in the development of the green bond market by clarifying the approach for issuance of a green bond. They are intended for broad use by the market giving: • issuers guidance on the key components involved in launching a credible green bond; • investors help evaluating the environmental impact of their green bond investments by ensuring the necessary information is available; • underwriters assistance by moving the market towards standard disclosures that will facilitate transactions. |

The Green Bond Principles cover reporting standards, and investors see the benefits of self-regulation over mandatory, fixed rules.

“To the extent that we can self-regulate we should,” says Faloon. “Setting a high standard that encourages peers into reporting could be the best route.”

The balance between regulation and flexibility is a delicate one and is something the World Bank is very aware of. The Green Bond Impact Report, launched by the organization at the end of July is widely viewed as an important first step towards improving this part of the market.

“I hope that as with green bonds to begin with,” says Lewin, “the World Bank will lead the way [in establishing a framework for impact reporting]. It is incredibly hard to do, but there must be some attempt to do it.”

In the meantime, difficulties in being able to compare and assess the standards and achievements of green bonds will persist.

“It can be hard to decipher the impacts when comparing apples to oranges in the different reports,” says Bailey. “It would be good to have some standards to make it easier to understand what was being achieved.”

Heike Reichelt, head of investor relations and new products at the World Bank, warns: “The reported numbers give you a sense of scale of the expected impacts for a particular project, sector and country. But comparing reports among issuers is challenging. Unless you are looking at various issuers that operate in the same country and sector and share the same methodology to measure, calculate and report the expected results, it is very difficult to make the case that the results are directly comparable. There are harmonization efforts underway, but there’s a long way to go – investors still have to be careful about making comparisons.”

For those yet to invest, this topic is equally as important.

“If we had that [standardised reporting] in place that would give us a lot of comfort and would really appeal to our clients who want to know what the long term achievements are,” says Milne. “I think that reporting is an important piece of the puzzle.”

While reporting standards may not yet be where investors want them to be, communication in general between issuers and investors is applauded.

|

|

|

|

Of those who have invested in green bonds, 74% said communication with issuers had become more intense. Reports of increasing roadshows and special one-to-one meetings arranged by underwriters are commonplace.

“Increased issuer contact has been beneficial for us because we are small,” says Bailey. “Everence’s overall AUM is $2.7 billion; for fixed income we are not quite at $1 billion. Having this green bond niche has been really helpful because we now have calls with companies we wouldn’t have spoken to before, they are interested in our thoughts and ideas.”

At Zurich Insurance, the management of around two thirds of assets is outsourced. This has meant a drastic change in the amount of contact with issuers for the internal team.

“Historically because of our business model, we wouldn’t have had much direct contact with issuers at all,” says Lewin. “As a result of what we are doing in green bonds we are starting to speak to them more often now.”

Improving transparency is seen as vital to the continued success of this market. Investors remain engaged and positive about where green bonds are going and are making impressive commitments to the amount they are prepared to invest in the sector.

Those commitments lead to inevitable questions about the pricing of these bonds. Survey respondents seemed unsure about when, or even if green bonds will ever be price through the secondary curve consistently. Although those saying the bonds will reach this point at some time in the next two to five years did edge ahead in the final tally.

“We’ve heard from syndicate banks that they are pricing green bonds flat to conventional bonds from the same issuer,” says Wigley. “We think that’s the correct thing to do. In Europe the vast majority of bonds are use of proceeds ones, so there is a link to projects. But the credit quality of the issue isn’t dependent on the project, it’s based on the issuer. So the credit risk is the same for a use of proceeds green bond as for a conventional bond. In which case, the return should be the same.”

Lewin agrees: “The yield for green bonds is generally speaking fair in light of the risk we are taking on.”

Bailey sees differentiation starting to take root. “I would be comfortable with accepting a slightly lower price for a wind or solar project with a similar rating to a coal project bond. I think longer term there is less risk than with coal. I think where it’s going to be difficult is for bonds where the underlying risk is similar to the classic version, there I don’t see why investors would go for it,” he says.

Faloon sees danger ahead if green bonds were to start pricing better than an issuers’ traditional bonds.

Euromoney green bond respondents |

• Large fixed income investors • Both those who had and had not already purchased green bonds • 38 verified responses • Together, the respondents were responsible for over $3.5 billion of worldwide investments to date in labelled green bonds • Majority (46%) of responses came from asset managers, with pension funds, insurance companies, individual investors, charitable organisations, investment trusts and others also represented in the data |

“Green bonds may trade through their standard debt because of the growing number of impact buyers. We are starting to see investors in the US now that just want the green in their portfolio and they may be willing to give up five to 10 basis points. But if it gets much more than that I think the potential for greenwashing abuse increases dramatically and that would be detrimental to the market. It’s a delicate dance between the green and the shift in the buyers and sellers that you will see in the market if that yield gets too far away from the equilibrium that is the issuers’ traditional rate of financing,” he says.

The growing popularity of ESG investment policies is touted by green bond market sceptics as the reason for the impressive growth in this sector, insinuating that investors are only looking for these opportunities because they have to. But Euromoney’s survey found that while over 60% of respondents had such a policy in place, over 40% of the investments made were not embarked on purely for this reason.

The bulk of respondents who were yet to invest in green bonds ranked the lack of opportunities as the primary reason for this decision, again demonstrating how high demand is, policy or not.

|

|

|

|

While there are many questions remaining about how this market will develop, support for it among investors is clear.

“I think this market will continue to grow, it’s not going to go away,” says Lewin.

“I am cautiously optimistic we will be making an investment in green bonds within two years,” says Milne.

Sponsored article |

|

Wigley believes the changes brought in by green bonds could spell a wider market shift.

“We believe the green bond is a very good product and is positive for the bond market generally,” he says. “It has increased transparency so the investor can actually see how their money is being used. Green bonds set a good example to the mainstream market. There is a lot of interest from our clients in knowing how their money is being used.”

Tackling climate change is becoming a part of everyday awareness. Reichelt has a vision for a very different market in the future.

“I think we can already say that green bonds are changing the way we think about bond issuing and investing,” she says. “No one can predict where things will go from here – but I do think that the green bond market is catalysing a development in the debt capital markets where issuers are focusing more on expected social and environmental outcomes of their projects, because investors are asking for that information. Decades from now, we may have a bond market where investors expect social and environmental outcomes from every single investment, regardless of whether it has a specific label or not.”

|