|

Illustration: The Red Dress |

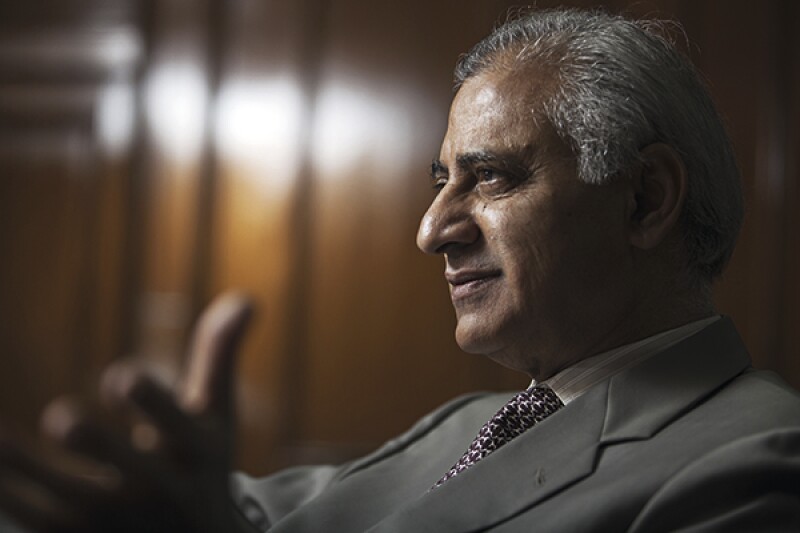

After a long career as a commercial banker, Ashraf Wathra – Euromoney’s choice as 2016’s central bank governor of the year – likes to describe himself as a central banker “of the times” for Pakistan.

What he means, he explains, is that on his now two year-watch as governor of the central State Bank of Pakistan (SBP), the longest any governor has served there in seven tumultuous years, Pakistan appears to be emerging from the IMF’s intensive-care ward.

Pakistan has been confined there since 2013. But now it is time, Wathra says, to position the SBP to consolidate this hard-won stability and push for solid growth. Market-oriented central banking is now appropriate. “I didn’t realize that when I was getting on the [SBP] stage,” he says. “I came to realize that as I was doing it.”

These are better times in chronically underperforming Pakistan. The markets are brighter and Wathra is getting high marks from his former banking colleagues in those markets. Wathra cites the near $24 billion in the foreign reserve coffers at the SBP, almost eight times the paltry $3 billion (barely three weeks’ import cover) at his disposal when he took over in 2014.

Pakistan’s banking sector is healthier too. The IMF singles out only two banks as out of step on capital adequacy, representing just 1.5% of the sector. At the nearby Pakistan Stock Exchange, market capitalization is 25% higher than at the end of 2013, while the main index is up 60%. Wathra’s job has also been made easier by a falling oil price.

With security tightened since the Peshawar school bombing of December 2014, Pakistan is telegraphing that it might be robust enough to go it alone again. Pakistan is set to complete, for the first time in its long history of external support, the three-year programme that the IMF tailored to stabilize the economy in 2013.

This is the $6.5 billion loan that then newly elected prime minister Nawaz Sharif secured from the IMF to stave off a balance-of-payments crisis in return for tighter fiscal discipline, a privatization programme and greater independence for the central bank. The last of the IMF lines despatched, Sharif and his finance minister Ishaq Dar now confidently say Pakistan can bid goodbye to the IMF.

'A little different'

It is time to prepare Pakistan for an expansion phase, says an emboldened Wathra, who seems at ease with a more market-oriented style at the SBP to urge it along. And, he says, he’s well-positioned to execute it because, after a 35-year career in private-sector commercial banking, he instinctively understands what the market wants, while balancing the regulatory needs of the state.

“I’m a little different from the other governors,” Wathra says. Starting his career in Lahore with Grindlays in 1978, Wathra says: “I spent my life in investment commercial banking. And I enjoyed that job very, very much. I had a very fulfilling career there.”

As for claims that he is ill-equipped for the monetary side of central banking, Wathra says: “We have a very competent team of economists, including one deputy governor. They do help me on monetary policy and the specialist areas.

“I assumed the charge of governor at a time when commercial banking the world over is in ascendency.”

But Wathra’s “of the times” remark hints at a deeper debate that runs through Pakistan about the role of the state bank. Pakistanis have tended to favour technocrats running the central bank, and all the better if they have been schooled at multilaterals like the IMF and World Bank, and far away from Pakistan’s polluting politics.

The former governors had an enviable set of skills that I may not have – and vice versa. But in these times, I think monetary economists would have been very, very ineffective - Ashraf Wathra

Politicians, particularly the generals who ran Pakistan for 43 of its 69 years, have generally been happy to oblige, to show a commitment to arms-length fiscal discipline. And in a country where politicians have had a penchant for corruption, sometimes an assertive central bank governor has been the only thing keeping things more or less afloat.

Pakistan’s reserves may look impressive compared with 2013 but by comparison, neighbouring India’s reserves are around $370 billion, poorer Bangladesh holds $30 billion and Indonesia $110 billion.

From independence until the mid 1990s, SBP governors tended to be senior civil servants elevated after long and loyal service to the state, before being pensioned off. Banking experience of any stripe was not a prerequisite and, common to many central banks of the era, independence was not a consideration either. Indeed, the 1953 SBP Act explicitly spelled out the Karachi-based SBP’s role as an obedient wing of the finance ministry in Islamabad.

But in 1993 came a dramatic change in thinking. Warding off a systemic collapse in banking, the SBP Act was revised and moves made to formally distance the central bank from the finance ministry. For 16 years from 1993, three professional economists – the so-called ‘multilaterals’ – ran the SBP, with all of them managing to serve out their appointed terms in succession.

Since former World Bank and Asian Development Bank economist Shamshad Akhtar stepped down as governor in 2008, there has been a revolving door at the SBP, with four governors in seven years. Until Wathra, the record was hardly stellar; in the five years from 2008, GDP growth averaged just 2.9%. By 2013, the Pakistan economy again found itself under IMF care.

Withering critique

In Pakistan, commercial bankers running the central bank are regarded as a different breed, as the ‘multilaterals’ have not minded pointing out. Soon after Wathra was confirmed as successor to another ex-commercial banker, Yasin Anwar, in May 2014, his appointment was subject to a withering critique in one of Pakistan’s leading newspapers The Daily News.

It was written by former SBP governor Muhammad Yaqub, one of the ‘multilaterals.’ Yaqub did not hold back. ‘The State Bank of Pakistan has been handed over to a governor and a deputy governor whose academic training is not even remotely related to monetary economics and central banking functions,’ Yaqub wrote.

‘Moreover, their work experience has been confined to retail commercial banking, which is of no use or relevance to central banking. These two have to rub shoulders with competent and experienced counterparts from other countries, both bilaterally and in multilateral settings, and are bound to cut a sorry figure.’

|

Ashraf Wathra insists he has never been a member of a political party |

And then, in language coup-weary Pakistanis understand only too well, Yaqub wrote: ‘Imagine what would happen to the defence of the country if a poorly trained head of a private security company is appointed chief of the army staff.’

If Wathra was wounded by the ex-governor’s attack, he does not show it. “A commander-in-chief could be from infantry or artillery, armoured or something else,” he tells Euromoney.

“It’s not a given. It was the commercial and investment bankers who gave birth to central banks. So who comes first? The mother or the midwife? Any economist coming from Washington or elsewhere to do this job would not have roots in the market and would not know the nuts and bolts and mechanics.

“In economies, there are times when you need a different skills set, in different situations,” adds Wathra. “Maybe 10 years from now, when the markets are more developed, then maybe a monetary economist can run the central bank better.

“The former governors had an enviable set of skills that I may not have – and vice versa. But in these times, I think monetary economists would have been very, very ineffective. For people who are not hands on, for them it becomes very challenging.”

The governor concludes: “It is more important to have qualification and expertise to give a pragmatic push to the country’s economy, which faces a different set of challenges. I think it works well for us, at this stage.”

Transformative years

Born in Pakistan's Punjab region, 60-year-old Wathra is the son of a judge. The youngest of six children, Wathra notes that none of his siblings followed their father in his profession, “a family tradition” he jokes that his own children follow. None of his three sons, all Canadians, followed him into banking or finance.

After a solid grounding at Grindlays from 1978, the young Wathra joined American Express Bank in 1982. A series of rapid promotions followed and by 1984, aged 26, he was Amex’s branch manager in Islamabad.

The 1980s were extraordinary, transformative years in Pakistan. The Soviet Union had invaded neighbouring Afghanistan in 1979 and by the early 1980s billions in aid and military support were pouring into Pakistan from the US and Gulf monarchies to finance what would be a decade-long anti-Soviet mujahedeen insurgency in Afghanistan. Washington’s disbursement regime used American Express Bank as its sole facility in military-run Pakistan, and these were boom years for the country, which suddenly found itself awash with money – and corruption.

“These were very interesting, active years,” Wathra says. “I was not even 27 years old and I used to be at the US ambassador’s dinner table at least twice a week. He used to just walk informally into my office. We had a lot to do because all the funds were moving through Amex.” He laughs, as he recalls the period: “Money was heading on to many places.”

After Amex, Wathra had short stints at Emirates Bank and Faysal Bank before joining Habib Bank in 1999. Although based in Singapore and then Dhaka as regional manager, Wathra sees joining Habib as something of a homecoming.

Meaning ‘beloved’ and ‘friend’ in Urdu, Habib traces its origin to a nation-building initiative by the country’s founding father Mohammed Ali Jinnah creating a commercial bank for the new independent Pakistan. Nationalized in 1974 but owned since 2002 by the Aga Khan’s Fund for Economic Development, Habib closely aligns its culture to the nation. For Habib bankers, it is almost a civic duty to work there.

Come on, give me a break, what you [the PPP’s former finance minister Hafeez Shaikh] did, you were in office for four years? Why didn’t you do any corrective measures?

- Ashraf Wathra

In 2008, he went to Dhaka with a brief from the Aga Khan to start a locally-incorporated bank in Bangladesh. This was a sensitive proposition, requiring careful diplomacy in Bangladesh, the former East Pakistan. Habib Bank had 300 branches when Dhaka was ruled from Islamabad, but after the 1971 independence war, these operations were seized by the new state.

During 2008, Wathra heard positive noises from the Bangladeshi authorities about his proposal. The non-partisan caretaker prime minister was the technocrat Fakhruddin Ahmed, a World Bank veteran and former Bangladesh central bank governor. But in late 2008, the nationalist Awami League, regarded as Bangladesh’s foundation party, was voted into office. Awami’s leader Sheikh Hasina Wazed, the eldest daughter of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, independent Bangladesh’s first president, became prime minister for a second time.

Wathra kept up the diplomacy but despite the considerable charity work that the Aga Khan does in Bangladesh – he had backed the microfinance bank Grameen – and the promise of huge investment, it became clear that his ambitions for Habib in Bangladesh would come to nothing. Wathra remembers the note he received from prime minister Hasina that said: ‘We don’t want to see signboards of a Pakistani bank all across the country.’

“I’d gone to Bangladesh with a mission and now I wasn’t comfortable there,” Wathra recalls.

By 2012, in Dhaka with Habib, Wathra says he started getting pressure from his family in Canada to retire. He had worked solidly for 33 years, but he felt there was unfinished business at home in Pakistan.

In September 2012 he joined the state-owned National Bank of Pakistan (NBP) in Karachi in charge of credit management. He had been at NBP just four months when a colleague told him about a deputy governorship at the central State Bank of Pakistan. Several candidates had been considered but the SBP and the People’s Party government in Islamabad could not agree on who should fill the slot.

Wathra claims he had a “marginal interest” in the SBP position. He says he was happy in his new post at NBP in Karachi but decided to go and see then governor Yasin Anwar anyway. They spoke for three hours and Wathra says it was the first time in his career that he had been “properly interviewed”, describing it as a “grilling.” Within minutes of leaving Anwar’s office, Wathra says the governor called him to say he would be recommending him to Islamabad for the post.

It was January 2013. Several weeks passed and Wathra plunged back into his work at the NBP. In mid-March, he was summoned to Islamabad to meet then finance minister Saleem Mandviwalla of the People’s Party, who told Wathra that the government was comfortable with him. He was offered the deputy governorship, with responsibility for supervision and regulation. “These were areas I know like the back of my hand,” he says.

But why the central bank, after three decades as a commercial banker? “I had worked at many banks, and I thought if I am getting a chance to get into the central bank, that this is something different for me,” Wathra says.

It felt nationalistic, he says, that it was doing something for Pakistan: “I was suddenly finding a purpose for myself.”

Political theatre

As deputy governor, Wathra watched on as relations between Islamabad and the SBP under Anwar deteriorated, particularly over the role of the IMF in the economy. In early 2014, Wathra says he got a call from finance minister Dar, summoning him to a meeting in Islamabad. Government sources tell Euromoney that Dar “was not comfortable” with Anwar, who had indicated he would resign as SBP governor.

“He [Dar] asked me: ‘What should we do?’ I said: ‘You should recruit a governor as soon as you can.’ He said: ‘Why don’t go you go in the next room and do me a job spec to get into the search mode?’” recalls Wathra.

What followed was Pakistani political theatre. Wathra says he sat in an adjacent ministry office and listed the qualities and duties required of a replacement governor.

“I took the print-out and gave it to him,” he recalls. “He said: ‘I have read this, but this is not you.’ I said I haven’t done it for myself, I am doing it for the kind of governor I think there should be. I am not aspiring.”

Somewhat controversially for a Pakistani official, Wathra admits that he had the then celebrated Reserve Bank of India governor Raghuram Rajan, a former IMF chief economist, in mind in fashioning the spec for an ideal central bank governor. “One time I shared that with Raghu, and he was laughing,” Wathra says. “We get along extremely well.

“He [Dar] had seen a little bit of my way of working, and maybe also getting some feedback from the markets as well, so he started leaning a little on me in those months.”

|

Wathra is working with Queen Maxima of the Netherlands to bring more Pakistanis |

When Yasin resigned, Wathra was acting governor and he quickly got to work: “My interaction with the government suddenly increased and I told my team that yes, I am acting, but I am not going to put off any decisions. I will take full responsibility.

“We had a lot of backlog. I think in those three months, the government and the finance minister got a taste of me. I was just making things move and trying to make them move on time, without being bureaucratic.”

He says his management style was more inclusive, with “much faster decision-making.” He cites his role in helping HSBC exit from Pakistan. HSBC had sought a meeting with finance minister Dar to complain about paperwork delays at the SBP, which had caused it to lose buyers for its Pakistani branch network.

“I said: ‘Let them go’,” recalls Wathra. “They were exiting almost 21 markets. I told them that HSBC were not leaving Pakistan for the first time, they were leaving it for the third time. Pakistan was strictly a marginal market for HSBC. I said not to worry, we’ll find you a buyer.”

HSBC would be sold to Meezan Bank in October 2014. “I said: ‘Make sure you give them [Meezan] at the right price. I don’t want them to suffer.’ It was tied off within days,” he says. “How can you hold somebody when they are not willing?”

Wathra’s initial appointment to the SBP as deputy governor was made under a left-leaning PPP administration in Islamabad. But his accession to the governorship in 2014 came after the PPP had lost power to Nawaz Sharif’s centre-right Pakistan Muslim League. But it was different for his predecessor Yasin Anwar, appointed under the PPP and replaced before his designated term ended when Nawaz’s PML came to power. “I think that was just chemistry,” says Wathra. He points out that Dar is a professional chartered accountant and is now in his third stint of heading the ministry, each time in a Nawaz administration. “He’s a very experienced person.”

Wathra insists he has never been a member of a political party and denies having any patron. “I have never gotten close to politicians,” he says. He is widely perceived to be close to Dar but he argues that partisanship had nothing to do with his elevation. Still, there are unwitting clues. SBP research that Wathra gives to Euromoney notes that the “Nawaz Sharif government” has reversed negative trends in the economy and national finances when a simple “government” reference expected of a neutral central bank would have made the same point.

As for the recent revolving door through the SBP, the pragmatic Wathra says confrontation from Karachi does not work with a political government in the capital. He says stubbornness and vacillation contributed to various predecessors’ terms ending sooner than legally obliged.

“Whatever the finance ministry’s priorities are, they should at least be considered by the central bank; that out of these priorities, are there some that could be our priorities, good for our objectives?” he says.

“So far I have not seen bias in senior government appointments. They have been broad-minded.” But a PPP administration, he claims, “would have been more harsh. They would say: ‘He’s their man, we don’t want him.’ They are more prone to that.

“The present government, when it comes to their dealings with the bureaucrats or the professionals, they do not bear any grudge, and not only in my case,” he says. “I can give you several other examples where people who worked closely with the PPP or the Musharraf regime, they were not removed or changed.”

Former governor Yaqub begs to differ. He tells Euromoney: “The government has made sure to have only such governors who obey their orders and lack in competence, experience and courage to manage the monetary policy and the banking system independently. They have let the banking system and monetary policy to be used to suit political and personal agenda of the rulers.

“They have not changed the [SBP] laws but in practice buried the reforms by appointing incompetent and compliant governors and bullying them to obey their orders,” Yaqub says.

Wathra is not a big fan of Pakistan’s financial press. He cites a 2014 petition filed by an activist to the Lahore High Court that sought to have him removed on grounds of incompetence from the governorship. The case was thrown out after five weeks, but it prompted a media feeding frenzy.

“They gave me a lot of negative publicity and a lot of attention,” says Wathra. “In our entire history, no deputy governor has ever received such attention.”

IMF lifeline

Pakistan's IMF lifeline was well underway by the time Wathra formally became SBP governor in 2014. But he says he “absolutely” supports its role in stabilizing the Pakistan economy. “There was nothing going right, our reserves were depleting, all the parameters were going south. We couldn’t do something in our own right.”

He deftly sidesteps the question of whether his backing for the IMF programme helped him ascend to the SBP governorship. “This government [of Nawaz] spent a lot of political capital to achieve this programme.”

Wathra ponders why Pakistan abandoned an earlier IMF plan in 2008/09 just as democracy was restored to the country. “Our economy was consistently on a downward trend.” He says that earlier IMF programme offered less rigorous conditions for the economy than the country has endured since 2013.

He takes particular aim at the PPP’s former finance minister Hafeez Shaikh, a prominent critic. “Come on, give me a break, what you did, you were in office for four years? Why didn’t you do any corrective measures? It was very, very obvious [that Pakistan needed IMF support],” he says, dismissing economic nationalists who oppose the IMF. “Would they have liked to see Pakistan defaulting?”

Now well into his third year as governor, Wathra is on track to do what none of his predecessors have managed this decade, namely finish a designated term. He says there is much more work to do and “for that I would need a second term”.

He wants to bring financial services to at least 50% of the many millions of unbanked Pakistanis by 2020, with the GDP lift he hopes will follow.

His unlikely collaborator in that effort is the Dutch queen Maxima, who was an Argentinian banker before she became a royal and patron of the G20’s Global Partnership for Financial Inclusion. Maxima launched the SBP’s Universal Financial Access initiative earlier this year.

Wathra’s retirement with his family in Canada will wait. And, politics aside, he hopes he will be able to dictate his own departure from the SBP.

“I’ll be here as long as I can add value,” he says. “The moment I cannot add value, I will step out myself.”