|

Illustration: Peter Crowther |

Building a capital markets union (CMU) was never going to be easy,” sighed former European commissioner for financial stability, Jonathan Hill, on July 13 as he addressed the European Parliament in the wake of the UK’s shock vote to leave the EU and his own consequent resignation. “I was never under any illusions about that.”

But he did not expect that it would need to be built in the post-Brexit atmosphere of bitterness and recrimination, and the legal and regulatory uncertainty that is now business as usual until the UK actually leaves. The question is, can it be built at all?

As much as European Commission president Jean-Claude Juncker would like to argue otherwise, the UK’s departure is a big blow to his key capital markets initiative. UK negotiators were at the core of the CMU scheme and Hill was its chief cheerleader.

“The UK has been an integral part of shaping the CMU agenda, both ideologically and technically,” says Caroline Meinertz, partner in financial regulation at Clifford Chance in London. “The UK regulators have had tremendous influence and input. That voice will now be lost. We have the same status, but our influence evaporated overnight.”

|

|

IN ADDITION |

|

Hill’s replacement, European Commission vice-president Valdis Dombrovskis, has been swift to offer the impression that the CMU is unchanged. “The possibility of Britain leaving the single market makes our work to build deeper capital markets in the rest of the EU more important than ever,” he declared in mid-September. “We’re accelerating our work on the CMU in order to bolster financial stability in Europe.”

There is no doubt that the EU needs deeper capital markets more than ever – and that is because it faces the loss of the dominant constituent of those capital markets if the UK leaves.

“Politically, Juncker and Dombrovskis are still saying that CMU is still on the agenda – the action plan produced a year ago is still a statement of intent,” says Michael Collins, chief executive of Invest Europe in Brussels. “Everyone in Brussels is invested in saying it is business as usual. It is our genuine belief that the reasons we needed CMU have not gone away.”

Paul McGhee, director of strategy and head of the CMU steering group at the Association for Financial Markets in Europe (Afme), believes that the initiative is no more exposed to the impact of the UK vote than anything else.

“Brexit has not stopped the momentum for CMU more than for other EU projects,” he tells Euromoney.

He does, however, concede that it is not great news for the project: “Brexit could create a transitional problem for CMU because so much buy-side capacity, liquidity and capital markets expertise is in London. Without the UK, Europe’s financial system is more bank-based and its capital markets are generally less liquid.”

Continuing with CMU as if nothing has changed may not, therefore, be the smartest course of action.

|

Michael Collins, |

“Will the results of CMU be as significant as they would have been?” asks Collins. “If we end up with really tough barriers between the UK and the EU following Brexit, they will not be. A lot of the activity that might benefit from CMU happens in London. If we were to end up with soft Brexit and the UK still in the European Economic Area, for example, all the benefits of CMU would remain. However, the further away from that we end up, the more the impact of CMU will be reduced.”

One of the CMU’s prime objectives is to reduce the existing barriers to cross-border investment within the EU. The aim of the initiative has always been to create deeper and more integrated markets in the region, not to address the issue of cross-border investment by and into EU firms globally. That may now prove to be a serious mistake and is one reason why the UK leaving cannot be dismissed as immaterial.

|

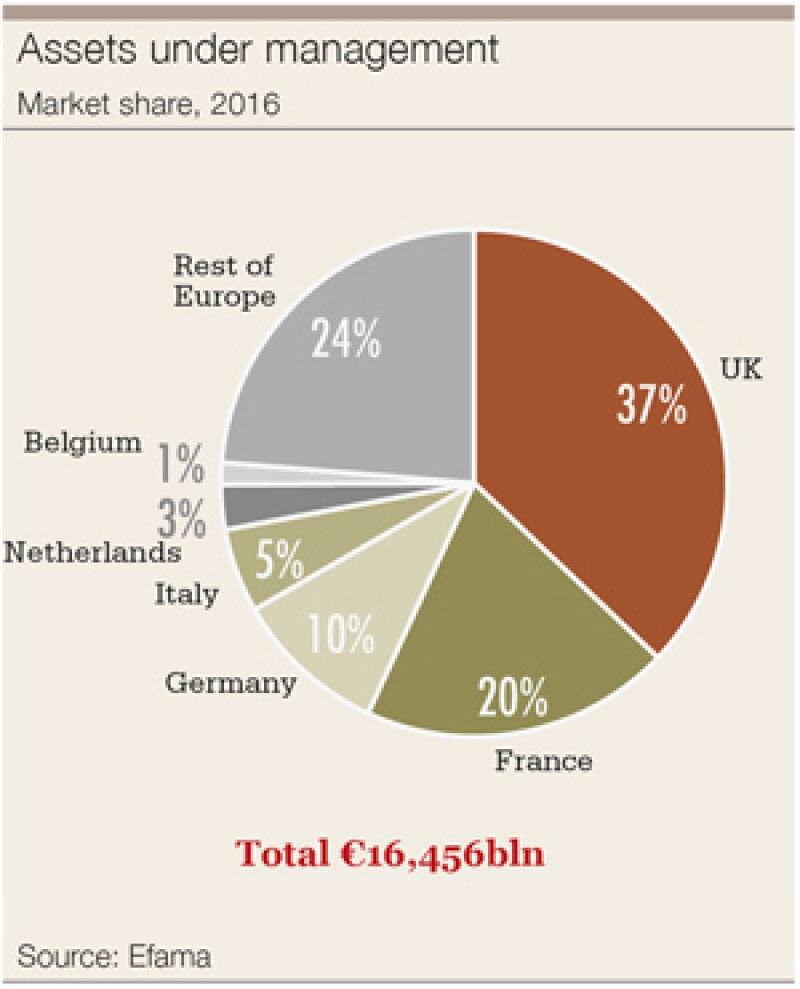

According to analysis from the New Financial thinktank, the removal of the UK from EU capital markets reduces total activity by a full quarter. Less than half of all capital markets activity in the EU takes place in EU27 countries, while in some sectors such as trading and hedge funds, more than three-quarters of EU activity takes place in the UK. EU27 pensions assets account for just 57% of the EU28 total, EU27 IPOs are 65% of the total, outstanding securitization is 72%, corporate bonds 78%, securitization issuance 79% and convertibles 89%. Bank lending still makes up 79% of corporate debt in the EU27, compared with 55% in the UK and 26% in the US.

Although CMU identified a number of target markets through which to tackle this problem, the areas where the objective could be most speedily realized were identified as the securitization market and the prospectus directive.

The prospectus directive was announced by Hill in November 2015 with the aim of making it easier for small and medium-sized enterprises to list by exempting smaller capital raisings from needing a prospectus, requiring lighter and shorter prospectuses within the EU and having a single access point for all prospectuses at the European Securities and Markets Authority (Esma). The departure of the UK from the EU will do little to hamper the implementation of the directive, which is seen as an easy win for the CMU as it can be implemented relatively easily.

“The reforms to the EU rules on prospectuses to make them cheaper are all good stuff,” says Collins. “Is it going to lead overnight to a flourishing IPO market in Estonia? No, but it is practical. You can have cheaper prospectuses in the EU, but if the nature of the long-term Brexit relationship means that there is a massive divergence in rules and it is more difficult for EU firms to list in London and to access the deep capital pools that reside there, then that negative dwarfs the benefit of the cheaper prospectus,” he warns.

In September 2015, the EC announced its intention to restore investor confidence in securitization through the introduction of its STS (simple transparent and standardized) framework for the sector. It also announced its intention to amend the Capital Requirements Regulation (CRR) to encourage the use of securitization as a means to get credit to SMEs across the EU.

Criticism

The promotion of securitization to its pivotal role within CMU is not without its critics. Economist professor John Kay has wryly observed that: “The proposal to promote fresh securitization has very little to do with the needs of Belgian business for new sources of finance and much to do with the needs of American investment banks for new sources of profitability.”

Euromoney has long questioned whether or not European securitization can possibly deliver what is being asked of it by CMU, and the prospect of Brexit only makes this challenge harder.

|

Paul McGhee, Afme |

“So far those initiatives which require legislative change such as securitization are moving less slowly than other parts of the CMU action plan,” admits McGhee at Afme.

Ian Bell is head of the Prime Collateralized Securities (PCS) Secretariat, which works to promote securitization in Europe, and is involved in promoting STS securitization, which would attract lower capital requirements under the CMU initiative.

“For the moment the impact of Brexit on CMU is nil,” he says. “That may reflect the distinction between the political shock that has been seismic and the fact that no one knows what the deal will look like when the UK leaves.” He observes everyone in Brussels involved in CMU going about their day as usual, despite the potential impact of the vote on their project.

“We can’t put everything on hold until we know. So we carry on. Juncker said this – CMU goes on. The priorities haven’t changed,” Bell tells Euromoney.

The harsher truth is that there is little impact on securitization because there is so little activity in the first place.

“The securitization market is in a coma anyway, so Brexit doesn’t really make a difference. It barely moves the dial,” Bell admits. “The question is how it would impact a potential revival if you have lost 25% to 30% of your market.”

The extent to which that market capacity is ‘lost’ depends on how the UK is treated as a third country to the CMU legislation on STS securitization.

“The third country dimension to financial market regulation has always been very sensitive,” says Collins. “In CMU, to some extent, the issues didn’t have a big third-country dimension. Hill was unapologetic that this was a workmanlike action plan. He didn’t want yet another grand plan for a revolution – he wanted to get some momentum and to get member states thinking bit by bit.”

|

|

|

But securitization does have a big third-country dimension. And how UK securitizers will access EU investors, and vice versa, is of great importance if the aim of CMU is to see this market grow. In financial services the UK wholesale banking sector has the most to lose from Brexit as UK-managed funds are habitually domiciled elsewhere and UK insurance firms active in the EU tend to operate through subsidiaries already. The UK therefore needs to establish equivalence for its financial services regulation swiftly in order for business lines such as securitization to continue.

“The reality is that a UK bank that wants to access EU investors using securitization will have to comply with EU rules,” says Meinertz at Clifford Chance. “This illustrates a point that has been made in many different contexts: we will end up in some way, shape or form implementing or complying with EU legislation.”

According to Open Europe, around a fifth of the UK banking sector’s annual revenue is estimated to be tied to the EU. And many EU banks are also highly reliant on the relationship; Deutsche Bank receives 19% of its revenue from the UK.

Third-country access is unlikely to have been top of the agenda for CMU’s securitization plans, however, because boosting intra-EU flows is the aim.

“The extent to which the role and status of a third country and whether there is equivalence has been an important factor varies legislation by legislation,” explains Meinertz.

What does not vary is the reluctance by all involved to go back to the drawing board and re-think third-country aspects of legislation in light of the fact that this will now refer to the UK as well.

“People are a little less likely to want to go further on third-country access right now as they don’t know what the Brexit implications might be,” says Collins.

Revisiting third country access is not automatically good news for UK firms. “The work that has been done on CMU is done, they won’t revisit it,” reckons one source close to the talks. “But for ongoing negotiations, such as those for Mifid II, there have been calls for UK MEPs to be excluded from discussions around third-country access.”

It is hardly surprising that those from the EU27 involved in CMU are not rushing to do the UK any favours.

“The discussion of third-country regime regulations will be down the list or nestled in a bigger regulatory discussion,” says Bell. “So the question is what will be the placeholder? We need something in the regulations that doesn’t hamper the situation down the line. Nobody was pushing for this before because nobody thought it would be about the UK.”

The concern is over lack of enforcement outside the EU. Bell suggests that originating banks from the UK could work within domestic securities laws and include memoranda of understanding (MOUs) in the securitization prospectus. Thus there would be a statement within the prospectus as to how the requirements of STS securitization have been met and an MOU to the effect that should the document contain an untrue statement, then the UK regulator will prosecute.

“Securitization is at the centre of the CMU changes,” Bell emphasizes. “Banks need securitization to fuel the real economy, and Brexit increases rather than decreases this. The point of STS is to carve out a family of instruments. If it is not possible for UK issuers to be part of that family, then liquidity will fall.”

Need over desire

Despite the political entrenchment in Brussels, the hope is that the need for liquid securitization markets will trump the desire for CMU to go on regardless.

“There is a timing and sequencing question here,” explains Collins. “Re-opening legislative provisions governing third-country access won’t happen until Article 50 is triggered. As the Brexit big picture becomes clearer, it will become easier to go back and start to have a more sensible discussion about what third-country access should look like.”

In trying to gauge the impact of Brexit on CMU the exact timing of the UK’s withdrawal is not the only murky variable. Given that it will be at least two years from March 2017 (if Article 50 is triggered as expected), the impact of likely market innovation over that period needs to be taken into account. The CMU initiative has been designed around the traditional securitization business of large banks securitizing pools of homogenous mortgages, but the market may look very different in a few years’ time.

|

Oliver Schimek, |

One person who hopes that it does is Oliver Schimek, co-CEO at online peer-to-peer lender CrossLend. Based in Berlin and founded in 2014, CrossLend is a marketplace lender that offers what it calls single-loan securitization, whereby investors can invest online in consumer loans that have been securitized on a standalone basis using a proprietary credit scoring algorithm. Scary as this sounds, what it demonstrates is that if a cost-effective method of making consumer loans investable by retail investors as well as institutional buyers can be developed using securitization, then the technique may achieve CMU’s aims in ways that the EC has never envisaged.

“We are making the banks P2P-capable by moving the plumbing of their origination machinery closer to investors,” Schimek, previously chief investment officer at Kreditech, tells Euromoney. “Pooled securitization is a blunt instrument in this regard, but we enable investors to invest into a portfolio of loans that have been securitized on a standalone basis and choose which they want to have exposure to.”

He believes that this technology could unlock big new pools of capital for SME lending. “Every loan gets scored and securitized. The data of the underlying asset are reflected in the final terms of the bonds. The cost of this automated process is low two-digit euros per loan, and we securitize already today consumer loans as small as €1,500.”

There is a base prospectus for the issuance and all loans are originated by partner German bank BIW.

“Single loan securitization is the most transparent way to transform a loan into a security and you as an investor can perform your own analysis on each loan as an underlying asset of the notes,” Schimek continues.

|

|

|

Speaking at the recent LendIt conference in London CrossLend’s other co-CEO, Dagmar Bottenbruch, declared: “This is an important contribution to CMU – we can play an important role here as a key engine of CMU. Banks can become peer to the process. Single loan securitization mitigates the cross-border issue and enables banks to get into other countries and lend.”

It is clearly early days, however, and initiatives such as this are trivial when it comes to addressing the funding needs of Europe’s corporates – particularly in an EU without the UK.

“CMU is not a reality, it is a political wish,” says Schimek. “Things are given – amongst others – a CMU label if they are seen as somehow freeing up bank balance-sheet capacity. Brexit could very well delay CMU, as everyone is waiting for something to happen. However, the new STS securitization is so desperately needed that I don’t think they will allow it to be delayed.”

Many involved in CMU feel that the UK’s departure from the project will, or at least should, have one clear consequence: to change it from an intra-regional initiative to a global one.

“There has not always been enough recognition from the Commission that markets are global,” says Collins at Invest Europe. “Everything depends on the policy of access by non-EU countries to the EU market. Our diagnosis was always that we should be thinking globally. The scale of the financial challenge in Europe is such that you have to conceive of CMU as a global project. The emphasis should be as much on the ‘market’ as on the ‘union’ element of CMU, as flows of capital are inherently global.”

Simon Puleston Jones, chief executive at the Futures Industry Association in Europe (FIA Europe), agrees that it will be a grave mistake for MEPs to focus on the EU27 markets alone post-Brexit.

“To successfully deliver jobs and growth in Europe, CMU shouldn’t just be about the 27 member states alone – it should be about the 27 plus 10 or so others, such as New York, London and Singapore,” he tells Euromoney.

|

“The CMU programme is focusing on cross-border investment within Europe. It would be even more beneficial to focus on cross-border investment globally,” he insists. “Brexit could have a significant impact on CMU if the response from continental Europe is to inhibit the ability of European firms to access global capital markets.”

If the project does take on a more global focus – which is in no way guaranteed – the impact of Brexit will clearly be far more muted. This will benefit UK banks, but also seems to be a logical response to recent developments.

“I hope people see the sense of having an open market and don’t go down the narrow path of restricting who can invest in EU transactions,” says Meinertz. “I agree that CMU will have to be more global. The purpose behind it was to make the EU capital markets closer to the US model and to get EU companies away from their reliance on the banks. That shouldn’t be done around geographical boundaries.”

Brexit fuels corporate bond dysfunctionThe European Commission is looking to accelerate its Capital Markets Union (CMU) initiative at the same time as the region’s capital markets are looking increasingly dysfunctional. Think tank New Financial data show that bank lending still makes up 79% of corporate debt in the EU27 while yields in the investment-grade corporate bond sector have entered negative territory. This is a reflection of how much corporate lending in Europe is sub-investment grade but also a clear illustration of why broader and deeper capital markets are so desperately needed by the region’s smaller companies. Mario Draghi announced the ECB’s Corporate Sector Purchasing Programme (CSPP) on March 10 this year and its impact on the investment-grade bond market has been dramatic. The introduction of a price-insensitive buyer that is now able to buy up to 70% of eligible corporate deals has had a big impact. Investment-grade issuance had hit €223.5 billion by mid-September, with spreads having ground in from 149 basis points over Bunds before the CSPP announcement to 111bp on September 26. More shockingly, according to Tradeweb, around 27% of the euro-denominated investment-grade corporate bond universe was yielding less than zero by mid-September, up from 22% in August. Brexit simply added fuel to the CSPP fire. The average yield on euro-denominated investment-grade corporate bonds fell to 0.9285% immediately after the UK vote, the lowest level since 1998, according to Bank of America Merrill Lynch. It only took until July for the market’s first negative-yielding corporate bond to be issued – albeit for state-owned German rail operator Deutsche Bahn. The €350 million five-year deal through BayernLB and Raiffeisen Bank yielded just -0.006%. By September two private sector issuers had followed suit: German consumer products company Henkel sold a €500 million two-year bond with a yield of -0.05% through BNP Paribas, Deutsche Bank and JPMorgan. French pharmaceuticals conglomerate Sanofi sold a €1 billion three-year bond that also offered a negative yield of -0.05%. BNP Paribas and Morgan Stanley arranged the latter deal. By late September there was no sign of any let-up in ECB corporate quantitative easing. Indeed, by October 25, the ECB had bought €35.8 billion-worth of corporate bonds since the CSPP began. The market expects further negative-yielding issuance from blue-chip corporates, but there is only so far that this phenomenon can run. The ECB can and will buy 70% of issuance, turning investment-grade corporate credit into effectively a quasi-rates product, but that still leaves 30% to be placed with institutional investors. Buying negative yielding bonds purely in the expectation that yields will go even lower can be an expensive game to play. If the EC is as determined to boost capital markets participation in Europe as it declares itself to be, it needs to have a functioning capital market to develop. This is far from the case in investment-grade corporate credit – and that distortion is embedded all the way down the credit curve. Artificially cheap credit may look good to Europe’s borrowers but will not look so good to the region’s investors when the cycle turns. For CMU to create truly deep and liquid capital markets it needs to be starting from a much firmer foundation than this.

|