It’s crunch time. China appears to have acknowledged what commentators have been saying with mounting alarm for years: that there is just too much corporate debt in China, and something needs to be done about it.

In October China’s State Council approved a programme of debt-to-equity swaps to bring down China’s soaring corporate debt, now estimated at the equivalent of $18 trillion, or 170% of GDP.

Reaction to the news has been mixed. China analysts and commentators have urged it to do something about the corporate debt load – with the IMF the latest to do so in a detailed working paper in October – but there is also concern that the measure fails to deal with an underlying problem and just lets errant companies and projects off the hook.

China has sought to insist that these will be market-oriented swaps that are only open to companies with good prospects. Lian Weiliang, an official at the National Development and Reform Commission, said at a briefing in Beijing on October 10: “Debt conversion is no free lunch. The relevant market players will make their own decisions, take their own risks and enjoy the benefits.”

|

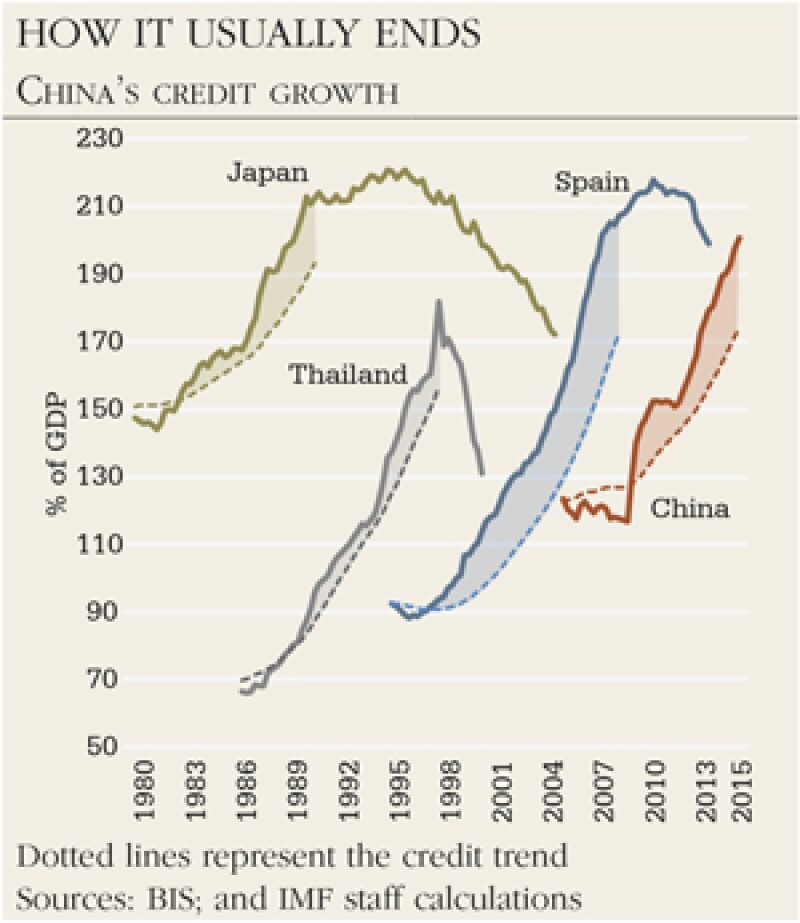

But if that’s true, then it might not be enough. Many Chinese enterprises are in a dreadful state and if debt-equity swaps really are driven purely by market forces, then most banks would run a mile before considering them. The State Council says, though, that banks will not be able to handle conversions directly anyway but must go through ‘agents’; it is not clear what that means, but analyst Judy Zhang at Citi believes they will probably be asset management companies, insurers, or indeed a new subsidiary set up by the banks themselves. The problem is this: several years ago China decided to rebalance from a model of external demand to domestic demand, a model that is heavily dependent on credit. Credit has correspondingly grown rapidly – about 20% a year between 2009 and 2015, according to the IMF — which in some senses is a good thing: it takes stable domestic savings and channels them towards productive investment.

The problem is that a lot of this credit has gone into the wrong areas, creating overcapacity in sectors such as iron and steel or construction. Now, the financial performance of those companies is declining and since they’re in heavy debt, that in turn creates a serious asset quality problem for banks.

“The authorities recognize the problem, but appear to be still searching for a fully-fledged strategy,” says the IMF in its paper. “There is broad evidence that booms of this size are dangerous.”

Strategic goals

At the heart of the problem are state-owned enterprises, which on average are even more leveraged and less profitable than private enterprises, mainly because their role has been to implement the strategic goals of government policy rather than to be prudent and profitable businesses. At a national and provincial level, authorities have been instructed to identify zombie SOEs – ones that have run losses for three years in a row and no longer fit national industrial policy priorities. The State-Owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission (Sasac) has identified 345 of these at a central level, and some individual provinces have even more: 830 in Liaoning alone, for example, and more than 3,000 in Guangdong.

So what to do? The government has already tried a few things, and the debt-equity swap policy should be seen as a continuation in that vein. Sasac has been told to resolve its zombie companies within three years and the provinces are trying to do the same. Capacity targets have been cut on coal and steel, and even healthier SOEs are now expected to undergo reform, with 10 pilot programmes underway. Debt-equity conversions appear within the suggestions in the IMF paper, among a host of other requests. The State Council says it will encourage mergers, bankruptcies and debt securitizations, all of them also applauded by the IMF.

But two concerns arise from the idea: firstly, whether it simply allows companies and SOEs to throw off their debt troubles without changing practices; and second, what it does to the banks. Analysts see it as a plus that zombie companies cannot participate, and that banks will not be forced to do anything; also that the size is likely to be limited.

In an October 10 report, Zhang at Citi says the market impact for the banks would be neutral. “We believe the key purpose of [debt-equity swaps] is to allow problematic companies, mainly SOEs, to have a chance of surviving,” she says. “Tax benefits will be provided to both corporates and banks as incentives for them to participate.” She says that banks should be able to digest an 8% to 17% NPL ratio in five to 10 years without impairing book value.

At Nomura, analyst Sophie Jiang says the programme is “positive for the banks, as it offers one more option for the digestion of qualified bad loans”, though there will likely be upfront write-down pressure when banks sell debt to a separate entity for a swap.

Since the announcement, word has started to spread of individual debt restructuring plans, including two involving China Construction Bank. It will conduct one debt-to-equity swap with Yunnan Tin Group and another, worth Rmb24 billion ($3.55 billion), for Wuhan Iron and Steel Group. Analysts in China say these are reasonable candidates for survival – local consultancy NSBO Research says in an October 12 note that Wuhan has “a relatively secure financial outlook” – but the clincher will be just how far down the spectrum of viability banks will be prepared to go in effecting these swaps.

As it is, NPL ratios are rising rapidly in China’s banking system, and are widely believed to be far worse than stated. Reducing corporate debt without crippling the banks is going to be a delicate balancing act.