Sometime in the late 1970s, Nemir Kirdar, the ambitious head of Chase Manhattan Bank’s operations in the Persian Gulf, boarded the Gulfstream II jet of David Rockefeller. Rockefeller, the then chairman of Chase, was bound for Muscat, Oman, where he was to meet Qaboos bin Said Al Said, the Omani sultan.

Kirdar, who accompanied Rockefeller on his annual tours of the Middle East, was excited at the prospect of meeting the sultan. Kirdar looked up to Rockefeller, whom he saw not only as a banker but as a world statesman in his own right. Thanks to him, Kirdar had already met ministers, sheikhs, crown princes, emirs and leading businessmen from across the region. On this occasion, however, his hopes were soon dashed.

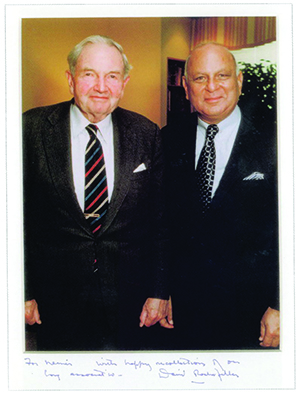

|

David Rockefeller and Nemir Kirdar |

During the flight, Kirdar was told Rockefeller would meet the sultan alone.

Kirdar was unhappy and complained, but his immediate boss Bill Flanz told him to accept the chairman’s decision. Soon, Rockefeller himself got word of Kirdar’s discontent and told him to stand down. To Kirdar, Rockefeller’s choice of a private audience made little sense. Reflecting on it in his memoirs years later, Kirdar wrote: “This seemed odd, if not a serious mistake.”

He continued: “Our business relied on having access to government officials and decision-makers, but persuading the relevant people to see us was often a struggle. If it was known, however, that Chase personnel had been personally received by the king, sultan or emir, we found that doors opened far more easily.” Rockefeller’s decision was a big disappointment to Kirdar because he knew that, to be successful doing business in the Middle East, one had to know the right people.

It was a lesson Kirdar learned early and never forgot.

So when the time came, nearly 40 years later, to select his successor at Investcorp, the Bahrain-based investment firm he was instrumental in founding in 1982 and which he had led ever since, Kirdar knew exactly what sort of person he wanted. Not a banker through and through but someone who could open doors around the Gulf, someone who would be received by the leading figures of the region: the king, sultan and emir.

Kirdar told his top management repeatedly that he wanted someone with the stature of a foreign minister. He found that person in Mohammed bin Mahfoodh Al Ardhi.

When Al Ardhi, an Omani national, was announced as the incoming head of Investcorp, in the summer of 2014, he had only recently become chair of the National Bank of Oman, and had sat on the board of Investcorp for six years – good, if unremarkable, credentials. But, importantly, he had also commanded the Royal Air Force of Oman for over a decade and been awarded the Order of Oman by Sultan Qaboos himself. From his years in the military he had, it seemed, acquired the contacts and diplomatic acumen to be the foreign minister Kirdar envisaged for the firm.

Al Ardhi took the helm as executive chairman in July 2015. Since then, he has met with political leaders around the Middle East and beyond – and begun to make his own mark on Investcorp.

Political ties

From its founding, Investcorp has been a firm that entertains close ties with the public leaders and institutions of the Gulf. Interviews with Investcorp management, including Al Ardhi, together with the information contained in the memoirs of Nemir Kirdar and in several US diplomatic cables, paint a picture of a business firmly rooted in circles of political power.

The formation of Investcorp was set in motion in 1979, when Kirdar and Jawad Hashim first discussed the idea of creating an investment firm that would serve the Gulf by establishing bridges with the west. At the time Hashim, an Iraqi like Kirdar, was president of the Arab Monetary Fund (AMF), a relatively new intergovernmental organization set up by the Arab League to promote the development of Arab financial markets. Hashim had been handpicked for the job by Saddam Hussein, the then president of Iraq, with whom he was close.

In Kirdar’s recollection, the idea for Investcorp originated with him. (On this and other details, Hashim has a different take. Apparently angered by what he perceived as Kirdar’s attempts to take all the credit for founding Investcorp, Hashim wrote an alternative account, ‘The true story behind the creation of Investcorp’, in which he says the idea for the firm was his own.)

In any case, both men agreed on the idea and Hashim invited Kirdar to join him at the AMF to work on it. Kirdar eventually did, in 1980, on a one-year secondment from Chase.

It was under the auspices of the AMF that Kirdar developed the plans for what would become Investcorp. And, according to Hashim, the loan Kirdar took out in 1981 to pay for his share subscription in Investcorp was guaranteed by Hashim himself.

From the very start, therefore, the lines between private and public sectors were blurred. Although Investcorp was to be a company held by private stakeholders, the involvement of the AMF and of Hashim certainly gave it an official aura.

In the lead-up to the launch of the firm, Kirdar travelled the Gulf for months, hoping to garner the support of the region’s wealthiest and most powerful individuals. He was successful. In 1982, Investcorp closed the list of its founding shareholders. The 336 names on that list were a ‘Who’s Who’ of the Gulf. It included seven Saudi princes, a member of the Omani royal family, a member of the Emirati royal family, 67 sheikhs from Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Kuwait, the UAE and Qatar, and several sitting ministers from around the region, including the then powerful Saudi minister of oil, Ahmed Zaki Yamani.

The board was also assembled in such a way as to project the image of a well-connected, established institution. Just like the careful political planning that goes into selecting a ministerial cabinet, each board member had to be of “the highest profile”, in Kirdar’s words, and represent a key constituency to which he sought to appeal: they came from Jeddah, Riyadh, the eastern province of Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Kuwait, Qatar, Abu Dhabi, Dubai and Oman.

As if to underline the highly political nature of Kirdar’s thinking, Investcorp’s headquarters were established in the diplomatic area of Manama, the capital of Bahrain.

From the start, Investcorp was widely understood to be a private-sector equivalent of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), the political and economic union of six Gulf monarchies – Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the UAE – founded in May 1981. In its first story on Investcorp, in 1983, Euromoney noted that “with the lines between government and private sectors traditionally blurred in the region, some see this parallel [with the GCC] as important in itself.”

In the same piece, the magazine quoted Ahmed Ali Kanoo, Investcorp’s vice-chairman, who said he could not “emphasize enough the great rewards to be gained from the Gulf states working together closely on political issues, on foreign policy and on economic policy.”

He concluded: “So there is this great sense of unity about Investcorp.”

At times that “sense of unity” had the distinct appearance of a conflict of interest.

Hashim, for one, joined the board of Investcorp without relinquishing his post at the AMF, and Abdul-Rahman Al-Ateeqi became chairman of the board while remaining an adviser to the then Emir of Kuwait. (Hashim did not remain on the board long. In late 1983, having fallen out of favour with Saddam and fearing he would be apprehended by the Iraqi Intelligence Service if he returned to the Middle East from his place of hiding in Canada, Hashim thought it safer to resign from Investcorp. Al-Ateeqi stepped down as chairman in 2015)

The practice of maintaining public positions while working for Investcorp continues to this day.

Hazem Ben-Gacem, who leads the firm’s European corporate investment division, is an adviser to the president of Tunisia, while Yousef Al-Ebraheem, a relatively recent addition to the board of directors, is an adviser to the Emir of Kuwait.

Imagine an economic adviser to the UK prime minister simultaneously sitting on the executive board of Société Générale, a bank incorporated abroad but affected by UK economic policy.

And, of course, the dozens of shareholders who are members of the Gulf’s ruling families and government cabinets have the ability to influence public policy decisions that could affect Investcorp.

'Opaque'

In 1995, Investcorp received its first notable piece of negative press coverage, when the US magazine Time accused the firm of being opaque and too close to the leaders of the Gulf. Among other charges, Time claimed that the Bahraini authorities had granted Kirdar the “extraordinary privilege” of being able to buy stock in Investcorp, a publicly traded Bahraini company – when only GCC-citizens had that right.

Time also reported that in 1992, Bahrain’s ministry of finance was a shareholder in Sports & Recreation Inc, a company that Investcorp had acquired.

“This would be roughly equivalent to the US Treasury Department’s putting money into a takeover arranged by a Wall Street buyout firm,” Time wrote.

Investcorp has certainly entertained warm relations with the leaders of Bahrain. Kirdar has often met the kingdom’s ruling family over the years.

According to Bahrain’s state news agency, during one such meeting in 2014, Salman bin Hamad Al-Khalifa, the crown prince of Bahrain, “highlighted the significant role Investcorp continues to play in Bahrain and the wider GCC region”. Bahrain’s ambassador to the UK has repeatedly promoted Investcorp on social media.

That public support, from the firm’s early days through to the present, has helped establish Investcorp as a credible investment vehicle for the Gulf’s wealthiest. It has at times also placed Investcorp and Kirdar at the heart of politically inspired projects outside the typical remit of a private-sector business.

He often had been rumoured to be headed for more senior positions in the government … However, an alleged falling-out with the senior leadership, including perhaps with the Sultan, delayed, if not derailed, such ambitions - Gary Grappo, former US ambassador to Oman

In 2006, for example, Kirdar, who is well liked by the rulers of Qatar – the emir is a friend of his and several members of the ruling family are shareholders in Investcorp – was chosen by the government of Qatar to take charge of a proposal to create a $5 billion bank to invest in Iraqi industries such as oil, gas and agriculture.

The project, which never came to fruition, was revealed by a confidential cable written at the time by the then US ambassador to Qatar, Charles Untermeyer, and published by Wikileaks.

In that cable, Untermeyer writes that the Qatari foreign minister, Sheikh Hamad bin Jassim Al Thani, wanted Kirdar to travel to Washington “to brief US officials on the idea”.

Investcorp’s privileged access to the political elites of the Middle East did not only bring advantages, however. It also sometimes caused the firm – and Kirdar – some headaches.

On one occasion, Kirdar recounts in his memoirs, Sheikh Zayed, the then president of the UAE, summoned him “without delay” to Istanbul. During two full days Kirdar was made to wait in a hotel for an audience with the sheikh.

On the third day he decided he had had enough and left, instructing Investcorp’s head of real estate, John Thompson, to take his place. Hardly a valuable use of Kirdar’s or Thompson’s time, especially since the task the sheikh wanted performed was no more than the valuation of a private residence he was thinking of buying.

But when one gets close to Emirati royalty, one is meant to accept these instructions without question; Kirdar was told he should consider it a “huge honour” to be summoned in this way.

More worryingly, on another occasion, Hussein, the then king of Jordan, pointed Kirdar to a dubious investment opportunity. In Kirdar’s recollection, Hussein said he knew a man called Don Aronow who had made his name building fast boats, which he sold to the Florida Coast Guard. That had apparently attracted the enmity of Cuban drug traffickers and Aronow had been shot dead. (Accounts of Aronow’s murder differ.)

Rather than discard the idea of such a risky investment, Investcorp agreed to the acquisition of Aronow Powerboats as a favour to the king. Investcorp bought the firm for $3 million in 1987, only to write off the investment with a total loss of $20 million just six years later.

Relative independence

It would be wrong, however, to think that Investcorp has been simply a vehicle for the whims of Middle Eastern rulers.

The picture is more nuanced than that. From the start, Kirdar knew the support of Gulf royalty would advance his project. But he also wanted Investcorp to enjoy relative independence from any one royal family or wealthy group.

Having a deliberately broad base of shareholders from across the GCC countries secured that goal. Having all six states represented in the list of original founders meant none felt excluded, yet none had a controlling stake in the firm either.

Investcorp was in many ways a novel business project. When it started, most investment firms in the Gulf were either family offices or sovereign wealth funds. Investcorp was neither. It brought together the wealth of hundreds of individuals from some of the states with the world’s highest oil production. People so rich that, at one point in his interview with Euromoney, Investcorp’s Ben-Gacem feels the need to coin a new phrase to describe them – the “über ultra-high net-worth individuals”.

The genius of Investcorp was to see that it could pool that vast oil wealth and invest it in the west.

Investcorp was also original in its investment methodology. Although it calls itself a bank, it always had more in common with a private-equity firm. But it also differed from the private-equity model.

Typically a private-equity firm raises money from investors, then places that capital into a dedicated fund where it is locked up for a predetermined number of years. The private-equity firm then uses that capital to buy portfolio companies. Once the fund is liquidated, the principal and, hopefully, profits are returned to the original investors. Investors pay a fee when they reclaim their contribution.

Investcorp does things somewhat differently. It identifies a company it wishes to buy, then buys it with its own money. Only then does it invite its regular investors – there are about 1,000 of these – to buy a stake in the company from Investcorp. Even after that process, Investcorp and its management retain a large holding in the company. Investors pay a fee upfront. Once Investcorp sells out, the investors reclaim the principal and any profits.

This way of doing things has been the object of some criticism.

If investors pick and choose which deals to participate in, they can end up with an undiversified and, therefore, risky portfolio. And the upfront fee, which is, by all accounts, substantial, means Investcorp reaps the benefits of the acquisitions it makes even before it has delivered a successful turnaround story.

But there are also a number of advantages. Investors like having more of a say in determining where their money goes. Meanwhile, Investcorp and its employees demonstrate their commitment to investment decisions by investing their own money; they can hardly be accused of passing all the risk on to their clients. When a portfolio company performs badly, Ben-Gacem says, his wife is the first one to tell him off, even before Investcorp, because he will have invested his own money in the business.

It was a culture shock, because until then I hadn’t really done much in business or investment - Al Ardhi

Investcorp made its name in the 1980s by buying luxury brands, turning them around and selling them for a huge return. Such was the case with American jeweller Tiffany, one of Investcorp’s earliest investments. Acquisitions of Breguet, Chaumet, Gucci and Saks Fifth Avenue soon followed. More recently, Investcorp has bought Italian menswear brand Corneliani and Danish jeweller and silverware maker Georg Jensen.

But Investcorp has always been willing to consider investing in more prosaic companies too: it has bought a convenience store chain, a motorway service station group, a chemicals maker and, most recently, a brand of UK potato crisps, Tyrrells.

Every year Investcorp considers hundreds of mid-market firms, luxury and workaday, preferably in the US and Europe, but also in the Middle East and north Africa.

Some investments do not work out – among them Aronow Powerboats. Others – watchmaker Breguet early on, more recently roofing firm Icopal – took years longer than expected to be salvaged and sold.

In the case of Chaumet, as reported by Time magazine, the former chairman of the watch maker, Charles Lefevre, went so far as to accuse Investcorp of using accounting gimmickry to disguise poor financial results.

Lefevre claimed that in 1990 Chaumet invoiced a nonexistent $4 million sale of jewellery to a customer in the Gulf to allow the firm to break even that year.

Lefevre also said that Chaumet sold products at inflated prices to a shell company in Switzerland called Lausanne Investments, allowing Chaumet to get poorly selling merchandise off its books without showing a loss. Investcorp indirectly owned the shell company, Time said.

Investcorp’s response to these allegations was that it had never misinformed Chaumet’s shareholders about the company’s performance.

But despite these setbacks and any Chaumet embarrassment, Investcorp’s overall financial performance has been startlingly strong. Since its founding, the firm’s average annual return has been 17%. Except in 2009, when the effects of the financial crisis were being felt, Investcorp has made a profit in every one of its 34 years.

In other words, the unusual business model Kirdar put in place works.

For better and worse

For Investcorp, what matters now is whether Al Ardhi will continue that success. And, importantly, whether he will maintain the kind of political ties that have defined Investcorp – for better and for worse – under Kirdar’s tenure.

The two share many traits, suggesting Al Ardhi may adopt some of Kirdar’s modus operandi. Both come from well-to-do Gulf families. Both grew up in the vicinity of power in their respective countries. Both were educated at prestigious western universities. Both are pro-royalist, pro-western and pro free-enterprise. Both had political ambitions but apparently turned to banking when these were thwarted. Each of them has published books and enjoys good relations with the political elites of the Gulf and beyond.

Kirdar was born in 1936 in Kirkuk, Iraq, an oil-rich city where his family held considerable sway. As representatives of Kirkuk in Iraq’s parliament, Kirdar’s grandfathers and father rubbed shoulders with the Hashemite kings and princes who then ruled over the country. Kirdar’s mother used to visit Queen Aliya, mother of King Faisal II, at the royal palace in Baghdad; on these occasions the young Kirdar, dressed in his best outfit, would play with the young king, who was his elder by just one year.

But Faisal II only lived to be 23. He died in the summer of 1958 when the Hashemite monarchy was suddenly overthrown in the military coup that established the Republic of Iraq and eventually enabled the rise of Saddam Hussein. On the day Faisal was executed, his friend Kirdar, then a student in Turkey, was waiting to welcome him at Istanbul’s international airport. Kirdar has remained fiercely loyal to the Hashemites throughout his life. And although they lost control of Iraq in the revolution, what survived of the Iraqi branch of the family still had connections in western political circles. Another branch ruled over Jordan and does to this day. Kirdar has maintained close relations with both the Iraqi and Jordanian Hashemites.

Kirdar was appalled by the political changes in Iraq. At one point, having returned to the country, he was imprisoned for 10 days by the new ruling Ba’ath Party. He decided he could no longer pursue the political ambitions he had nurtured in Iraq and that his best prospects lay in the US. There he continued his studies and began his banking career, starting off as a teller at First National Bank of Arizona, then moving up the ranks and eventually joining Chase Manhattan Bank. It was with Chase that he returned to the Middle East, having asked in 1975 to be posted to Abu Dhabi. In 1977, after having clinched a big financing deal in Qatar for Chase, he became the head of the bank’s new Gulf division. From there it was a straight road to Investcorp. By the time he co-founded Investcorp, his banking career had already spanned two decades.

|

| Al Ardhi meets Colin Powell |

Over the years he developed ties with the world’s powerful. He wined and dined Middle Eastern royalty and western politicians alike. At the Villa Serenada, Kirdar’s home in the south of France, he has entertained Prince Charles, George HW Bush, Colin Powell, former US secretary of defense William Cohen, King Abdullah II of Jordan, the former Empress of Iran Farah Pahlavi and the Emir of Qatar.

Less is known of the reticent Al Ardhi. He has not, as yet, published his memoirs. (In 2008 he published a novel, ‘Arabs down under’, which is partly autobiographical. It is based on a trip he made to New Zealand and his views on relations between the Middle East and the west.)

Al Ardhi was born in 1961 in Sur, Oman, the son of the Omani head of customs. When he was eight years old, the family moved to a house near a small airstrip, where a military aircraft would sometimes land to deliver supplies to the army. He was taken by the buzz of engines in the sky. At the age of 17 he joined the air force as an officer cadet.

Al Ardhi spent the following years rising through the ranks. By 1990, when the Gulf War began – the only conflict Oman was involved in during his time in the military – Al Ardhi was commanding the air base on Masirah Island. That base was used during the war by US and other coalition forces as a launching pad for strikes on the forces of Saddam Hussein that had invaded Kuwait. Al Ardhi says he missed part of that conflict because in 1991 he moved to the US to study at the National Defense University, an institution funded by the US Department of State and devoted to training high-ranking military officers. He returned to Oman in 1992 and was made air vice-marshal, the highest position in the Royal Air Force of Oman (RAFO).

He headed the air force for the next 11 years. He also chaired the Oman-US and Oman-Iran military committees, making him, on military matters, the principal Omani point of contact for top US and Iranian officials. Al Ardhi tells Euromoney that his counterparts on these committees included a US assistant secretary of defense and some of Iran’s top military officials from the Revolutionary Guards. According to an unclassified Pentagon memo, on at least one occasion in 2002, Al Ardhi also met Donald Rumsfeld, the then US secretary of defense. During his time as air vice-marshal he also developed political connections at the highest level of Middle Eastern politics: Al Ardhi met the then president of Iran, Mohammad Khatami; the then president of the UAE, the late Sheikh Zayed; and King Abdullah II of Jordan.

|

|

| Meeting the men at the top. Al Ardhi with, clockwise from top left, Sultan Qaboos of Oman (l); the then president of Iran, Mohammad Khatami; and the then president of the UAE, Sheikh Zayed |

|

|

|

In 2003, after 25 years in the air force, Al Ardhi retired from the military.

A confidential diplomatic cable written in 2007 by the then US ambassador to Oman, Gary Grappo, gives a possible reason for his retirement.

In the cable, released by Wikileaks, Grappo writes of Al Ardhi: “He had risen quickly within the RAFO ranks and was the youngest Omani in history to command one of the Omani armed forces… He often had been rumoured to be headed for more senior positions in the government, including that of the current de facto number two in Oman, minister of the Royal Office and supreme commander of the Armed Forces, General Ali bin Majid al-Ma’amari. However, an alleged falling-out with the senior leadership, including perhaps with the Sultan, delayed, if not derailed, such ambitions.”

Grappo adds: “Rumours persist in various Omani circles that he is being ‘rehabilitated’ and will return to government service at ‘the appropriate time.’ However, he told the Ambassador that while he would enjoy a return to government service in ‘a meaningful policy position,’ he has no immediate plans to do so.”

Grappo declined to be interviewed for this article.

Al Ardhi tells Euromoney that he left the air force because the work was hard and he felt that he had served long enough. Al Ardhi shifted his attention to the business world. He moved to the US once again, this time to study for a Master in Public Administration at the University of Harvard.

Once he completed that degree, Al Ardhi tells Euromoney, he returned to Oman, where he began his business career in 2004 as chairman of Rimal Investment, a company founded by his father and an uncle. Al Ardhi had at that point no practical experience of finance, except for his work on Oman’s military budget. As head of the air force, he worked on such things as weapons contracts. According to Grappo’s cable, he had been an “ardent supporter” of Oman’s purchase of F-16 fighter jets from the US in 2002.

Al Ardhi says of taking over Rimal: “It was a culture shock, because until then I hadn’t really done much in business or investment.” But with assets under management of between $30 million and $40 million, Rimal was, by the standards of the Gulf, only a small enterprise.

Soon, however, Al Ardhi’s political connections helped him advance his career. Al Ardhi knew the crown prince of Abu Dhabi, who in turn knew Kirdar – it was the prince who first introduced them. Kirdar took to Al Ardhi, whose Harvard education, military career and political connections impressed him.

In Al Ardhi, Kirdar felt he had found, as one Investcorp employee puts it, “an undeclared foreign minister”. In 2008, Al Ardhi joined the board of Investcorp.

After that, Al Ardhi joined the National Bank of Oman, where he was deputy chairman for three years, then eventually chairman for just six months before being announced as the next executive chair of Investcorp. So while he had some experience of banking before clinching the top job at Investcorp, Al Ardhi had far less than Kirdar when he founded the firm. What Al Ardhi did have, however, was an impressive network of contacts.

Direction

While he may not have decades of experience in finance behind him, Al Ardhi certainly has a broad sense of the direction he wants Investcorp to go. He tells Euromoney that as chairman his first question to the board and top management of the firm was: “Why aren’t we Blackstone?”

At that point, in mid 2015, Investcorp had about $11 billion of assets under management. Blackstone was roughly 30 times larger. Al Ardhi’s question was not simply about size; he also meant Investcorp should be as widely known as the US private-equity group. Nevertheless, Al Ardhi told his team they should strive to double Investcorp’s assets within the next five to six years.

A year on, that objective had been reached. On October 25, Investcorp announced that it was buying the debt management business of UK private-equity firm 3i, adding $12 billion of assets to its books.

But rather than settle for that, Al Ardhi quickly made clear that he wished Investcorp to be larger still. In a meeting after the 3i acquisition had been arranged, Rishi Kapoor, a senior manager, was talking about how the firm had just about reached its medium-term objective when Al Ardhi interrupted him to ask: “When do we reach $100 billion?” Al Ardhi wants Investcorp to be bigger than it has ever been.

As it sets about continuing its expansion, Investcorp has gained the support of an important player in Gulf finance, Abu Dhabi’s sovereign investment fund, Mubadala Development Co. Investcorp announced earlier in 2016 that Mubadala would be buying a 20% stake in the firm – a sign that Abu Dhabi is confident in Investcorp’s long-term prospects.

This expansion is not all Al Ardhi’s doing. Before his appointment as chairman, Investcorp had grown in a number of new directions. Beyond the private equity-like acquisition business, which has been the bedrock of Investcorp from the beginning, the firm has developed a hedge fund business since the mid-1990s that now totals $4 billion and is backed mainly by US investors. Investcorp has also developed a large real-estate division and created three funds devoted to investing in small and medium-sized technology firms.

But the acquisition of 3i’s debt management business takes Investcorp down a new avenue. And Investcorp is growing all of its existing segments, too. In November 2015, the firm grew its hedge fund business with the acquisition of the $800 million hedge fund of funds unit of SSARIS Advisors; over the year ending September 2016, Investcorp’s real estate acquisition activity in the US reached record levels, with $1.6 billion of transactions signed; and it is in the process of launching its fourth tech fund.

Al Ardhi’s approach is different. 'Just send me an email,' he tells his staff

There are still challenges ahead. The halving of the price of oil over the last two years may result in Gulf investors having less capital to place in Investcorp – although it could also drive them to seek further investment opportunities in the west, to diversify away from oil.

And a former hedge fund partner of Investcorp, Kortright Capital, is suing Investcorp in the southern district of New York for $100 million in damages.

Kortright alleges in its complaint, filed in September, that Investcorp breached its obligations to the hedge fund by pulling its money out of it just as it was about to be bought by UK-based asset manager Man Group, leading to that takeover falling through and Kortright being liquidated.

Investcorp has called the claim “groundless” and vowed to defend itself vigorously.

But that is not clouding the mood at Investcorp. Its top management tell Euromoney how excited they are about the changes that are taking place. David Tayeh, head of corporate investment in North America, and Tony Robinson, chief financial officer, joined Investcorp after Al Ardhi took over, apparently because they believed in his vision for the firm.

Al Ardhi says he also wants to shake some of Investcorp’s old habits. The Kirdar way was slow, very slow. As Kirdar told Euromoney in 1998, every October he used to ask the firm’s 20 most senior partners to write a 40-page report critiquing themselves, their colleagues and each division of the firm. Kirdar would then lock himself away for five days over Christmas to ingest every line of those 800 pages.

Then, every January, the 20 partners would join Kirdar for a two-week planning session in Florida, during which he saw each one of them individually, spending hours discussing their reports. After that, Investcorp would have eight days of general meetings – 14 to 16 hours a day – analyzing the firm, its competition and the economy. Finally, in February, each of the 20 got a sheet of paper outlining what the firm wanted from him and his team over the year to come.

Al Ardhi’s approach is different. “Just send me an email,” he tells his staff. Though Investcorp now controls $25 billion of assets, it has only a little over 300 employees spread across five offices, making it possible to interact in this way.

There are some things of Kirdar’s that Al Ardhi wishes to keep, however. Face-to-face interaction with its investors has always been a hallmark of Investcorp. The firm goes so far as to hand-deliver documents. It has a devoted team of placement and relationship managers who travel to see its owners and clients. Al Ardhi is keeping this expensive personalized service – in fact he is doubling the number of these managers in the next two years from 40 today.

Yet it is unclear how directly involved Al Ardhi is in the daily business of running Investcorp. When Kirdar, who was both chief executive and executive chairman, retired, two new co-CEO positions were created to supplement the position of executive chairman. The co-CEOs, Mohammed Al-Shroogi and Rishi Kapoor, have decades of banking experience between them and have worked for many years in top management positions at Investcorp. Either one of them would have had the profile to lead Investcorp. Instead, they both support Al Ardhi, taking care of much of the day-to-day work of managing the firm.

|

| Al Ardhi hosted a dinner in London for Spain’s former king Juan Carlos |

Meanwhile, just as Kirdar had hoped, Al Ardhi spends much of his time meeting the political leaders of the Middle East and beyond, making contacts that may one day serve the firm.

Since becoming chairman, Al Ardhi has already hosted a dinner in London for Spain’s former king Juan Carlos; convinced former chief of MI6 John Sawers, whom he knows, to speak at Investcorp’s investor conference in Bahrain; met the high-calibre members of the firm’s European advisory board (which include former secretary-general of the United Nations, Kofi Annan, and former high-ranking European politicians), as well as the crown prince of Bahrain and Kuwait’s minister of finance. He has also travelled to Beirut to meet Lebanon’s former prime ministers Saad Hariri and Najib Mikati on a two-day trip that one employee of Investcorp said had the aura of a “visite d’état”. (Hariri reclaimed the position of prime minister of Lebanon in November 2016.)

World of trouble

Kirdar eventually learned why Rockefeller had chosen to meet Sultan Qaboos alone all those years ago, in the late 1970s. The meeting had, in fact, nothing to do with Chase. Instead, Rockefeller was carrying a confidential message from the White House to the sultan.

Rockefeller, who is now 101 years old, was prone to blurring the lines between business and politics. Such was his influence in political circles that in 1976, Henry Kissinger, the then US secretary of state and a man he knew well, was directly involved in organizing one of Rockefeller’s banking trips with Kirdar around the Middle East, according to an unclassified diplomatic cable. And his access to top public officials certainly gave him an advantage in doing business. Rockefeller writes in his memoirs that in 1974 he met the Shah of Iran in the Swiss alpine resort of St Moritz, hoping that Chase would be granted a physical presence in the seemingly impenetrable Iranian market. There and then, the Shah agreed to allow the establishment of an entirely new bank in Iran, part-owned by Chase: no tender necessary and no questions asked.

But Rockefeller eventually learned that getting too deeply involved with public figures could also bring him a world of trouble. In 1979, after the Shah was deposed in a bloody revolution, Rockefeller, with others, successfully lobbied president Jimmy Carter to allow the Shah into the US – a decision that precipitated the Iran hostage crisis and caused Rockefeller to be subjected to intense public scrutiny and criticism.

Although Kirdar, who is now 80, never found himself in the middle of an international crisis, he too became the object of journalistic scrutiny for his blurring of business and politics. Through the many political contacts he had made during his banking career, Kirdar sought to influence US policy on Iraq. In the 1990s he met former president George HW Bush, Kissinger and the sitting director of the CIA, Jim Woolsey, to promote (unsuccessfully) the resumption of Hashemite rule over Iraq. And in 2003, in the early months of the US occupation of Iraq, he met the then US national security adviser, Condoleezza Rice, to guide her on how to draft the new Iraqi constitution (again unsuccessfully).

But one meeting in particular, with sitting president Bill Clinton in 1995, brought him grief, after it emerged that the deputy chief of staff to Clinton received a message before the meeting saying that Kirdar was “good for a solid million” – suggesting he would make a $1 million political donation were he to meet the president for just five minutes. A spokesman for Kirdar later said no contributions were solicited and none were made, but the episode highlighted the sort of problem that can emerge when clear boundaries are not drawn between wealth and political access.

Al Ardhi also gets involved in political matters. Years after leaving the Omani military, when he was the chair of family business Rimal Investment, Al Ardhi continued to involve himself in diplomatic affairs. In 2007, Al Ardhi met the US ambassador to Oman, Grappo. In that meeting, he shared with Grappo information he said he had acquired during a recent visit to Iran from a “close adviser” to Ali Larijani, the then secretary of Iran’s Supreme National Security Council, regarding that country’s nuclear ambitions. Al Ardhi, who is now 55, was acting as a conduit between Iran and the US, just as Rockefeller had done three decades before.

Rockefeller, Kirdar and Al Ardhi – three generations of bankers doing business in the Gulf. Three generations of bankers who fancy themselves not just as businessmen but also as foreign ministers.

Al Ardhi’s ability to meet that standard was key in Kirdar’s decision to appoint him head of Investcorp. Al Ardhi has certainly proven that he is comfortable dining with royalty and participating in international diplomacy. But at this time of expansion and change for the firm and with transparency said to be an increasingly important part of banking, even in the Gulf, Al Ardhi may wish to do something altogether more simple and boring – be an executive chairman. No more, no less.