When JPMorgan reported its second-quarter results on July 14, everyone was desperate to hear what the bank saw coming next in terms of consumer spending and household creditworthiness – and what this might mean for the country’s economic recovery.

Chief executive Jamie Dimon was crystal clear on the analysts’ call.

“We don’t know.”

He said: “I know, at least I think, you’re going to have a much murkier economic environment going forward than you had in May and June – and that you have to be prepared. You’re going to have a lot of ins and outs. People get scared about Covid. They’re going to get scared about the economy, small businesses, the companies, bankruptcies, emerging markets.”

JPMorgan, like the Federal Reserve, plans for various outcomes including its base case, which Dimon fervently hopes for, an adverse case and even an extreme adverse case. “They’re all possible,” he said.

We don’t know the probability of [another shutdown]. By the way, we’re wasting time guessing

The bank concentrates on five potential paths forward for the economy. Dimon didn’t waste much time on the V-shaped recovery the sell side was touting back in April. He referred instead to the Fed’s W. “Their W case is that Covid comes back in a big way in the fall and you have to shut down the economy again. And obviously, we’ve got to be careful. We don’t know the probability of that. We simply don’t know.”

And he had one final point to make. “By the way, we’re wasting time guessing.”

In fact, JPMorgan’s second quarter results were defined by two very precise and very large numbers: record high revenues of $33.8 billion and another hefty reserve build of $8.9 billion against credit losses. That comes on top of the $6.8 billion already set aside in the first quarter.

The current expected credit losses accounting rules require banks to reserve against lifetime future losses, according to all that they know today about borrowers’ ability and willingness to service their debts. To do this, JPMorgan executives must attach varying probabilities to their five possible outcomes. Guessing may well be a waste of time: banks still have to try though. And it looks, from its best estimates, as if JPMorgan is attaching a higher likelihood to adverse, possibly extremely adverse, economic scenarios.

Here’s Euromoney’s best guess: no bank will be better placed to cope with whatever unfolds from here than JPMorgan. That is just one reason why it is our best bank for 2020. Anyone with any spare money left to put aside seems to agree with us.

Chief financial officer Jennifer Piepszak reports that, in the second quarter: “We saw record consumer deposit growth of 20%, up over $130 billion year on year and firm-wide average deposits were $1.9 trillion, up about 25% year on year and 16% quarter on quarter.”

And this came even as companies that had drawn their revolving credit lines at the start of the crisis and deposited funds at the bank repaid and ran those particular deposits down.

With lower-for-longer interest rates and falling loan demand, that deposit inflow is not a great bounty for the banks’ shareholders. But it is a clear demonstration that JPMorgan still stands out as a safe port in a storm.

One more reason…

It is strongly capitalized, has deep liquidity reserves, unrivalled management and has shown an ability to go the extra mile for both small and large businesses through the crisis, emerging, for example, as the biggest originator of Small Business Administration payment protection programme loans, having gone into the pandemic ranked number three among SBA lenders.

And there is one more reason for naming it our best bank: it earns a ton of money.

Since 2018, JPMorgan has been making pre-provision net income on average of $13 billion per quarter, which builds 60 basis points of additional common equity tier-1 (CET1) capital every three months.

The bank has, for now, paused share buybacks to retain more of this, while it continues to pay dividends. It has a CET1 ratio of 12.4%, compared with a regulatory minimum requirement of 4.5%, rising to 11.3% after all the various supplementary capital buffers are added on.

Had it suspended buybacks in 2018, JPMorgan would be running a 15.5% CET1 today, even while still paying dividends. It will keep on paying these unless its extreme adverse scenario – a 14% contraction in the US economy for the whole of 2020 and 22% unemployment by year end – sets off some kind of doom loop that would see it dip into its regulatory capital buffers. Dimon says the bank could take another $20 billion of loss reserves before this happens.

Maintaining its so-called fortress balance sheet has been a core principle of the bank for the past 16 years, ever since Dimon arrived at JPMorgan following the merger with Banc One in 2004.

The discussions with CFOs and treasurers became quite rational very quickly

When Euromoney interviewed Dimon in 2019, he explained how his thinking was guided by his father’s experience as a stockbroker.

“In the recession in 1974, which is one of the worst we’d ever had until the global financial crisis in 2008, I saw the vicissitudes of markets. In ‘74, I remember the limousines were off the streets, restaurants being closed. And then the same thing in 1982. Inflation hit 12%, the 10-year bond yielded 14.75%. People would say that can never happen again. And I would say: ‘You don’t know that.’ And I would make a list of all the calamities we had from Penn Central to Mutual Benefit, the failures and bankruptcies.

“Listen: these things happen. Some are predictable and some are not. You are going to have cycles. But you also can have financial services companies blowing up and you have to be prepared,” he told us.

The fortress balance sheet was quite unfashionable back in 2004 when banks happily levered up, like large hedge funds, to chase higher returns on equity and bonuses. But it made JPMorgan the big winner from the great financial crisis.

Since then, regulators have forced other banks to follow its example and JPMorgan’s balance sheet is not quite the distinguishing characteristic it once was. Its earnings power is however.

Even in the second quarter of 2020, after taking $1.6 billion of actual charge-offs, as well as the $8.9 billion reserve build for expected future losses, the bank still reported pre-tax profit of $4.7 billion, for a return on tangible common equity of 9%.

We saw record consumer deposit growth of 20%, up over $130 billion year on year

In the worst period since the great financial crisis it is generating better returns than the large European banks do during boom conditions.

HSBC, for example, which has been a similar safe haven in past crises, earned a 3.8% return on tangible equity for the first half of 2020, after adding another $3.8 billion for loss reserves in the second quarter to the $2.9 billion taken in the first.

JPMorgan’s preeminence is the final proof of the wisdom of running a diverse business model, which survived calls after the last crisis to break the big banks up and separate deposit taking from investment banking.

This year, the corporate and investment bank has paid for the reserve building, which has been higher at the consumer bank.

For the second quarter of 2020, the corporate and investment bank (CIB) reported its highest quarterly revenue ever, with investment banking fees up 54% and markets revenue up 79% year on year, each representing record performances.

Excluding the gain from the IPO of a strategic investment in Tradeweb in 2019, fixed income markets revenue at JPMorgan was 120% higher in the second quarter of 2020 than a year ago.

Stepping up

So extraordinary have this year’s events been that one almost forgets that Dimon himself suffered a heart attack and underwent emergency surgery at the start of March.

And while the chief executive returned to work in April, it was the bank’s two co-presidents and co-chief operating officers that had to fill his shoes and lead it through the start of the crisis – Gordon Smith, head of consumer and community banking and Daniel Pinto, head of the corporate and investment bank.

As Pinto flew across the Atlantic ahead of a looming travel ban, and with the bank’s employees dispersing to their homes instead of to disaster recovery sites, he must have wondered how the bank would cope.

Outlining JPMorgan’s response to large corporate customers that needed its help, Pinto tells Euromoney: “In the CIB and the commercial bank we were hit by a wall of credit requests, which, within reason, we were able to fulfil. Draws on revolvers were two times what we saw in the great financial crisis. Being in a strong capital and liquidity position, we were able to deliver for customers that were eager to conserve funding as soon as they could.”

What followed was extraordinary. With commercial paper and bond markets seizing up, the Federal Reserve rushed to announce it would buy into them to support corporate access to funding. The first highly rated investment grade corporate issuers returned to the primary market, central bank support ensured big institutional order books, strong demand enabled good aftermarket performance, sellers wanted a piece of the action and became buyers, outflows from bond funds reversed.

It was a classic positive feedback loop. And JPMorgan was at the centre of it.

“We had humongous credit demand. We had the capital to meet it and while we had to assess the credit risks, we did not lower our credit standards. If anything, we slightly tightened them. But we were still able to arrange financing for borrowers from some of the most troubled sectors, including airlines, hotels and cruise lines,” says Pinto.

Carnival’s remarkable voyage

One of the most remarkable transactions of 2020 was the $6.25 billion combined package of senior secured bonds, convertibles and common stock that JPMorgan arranged for Carnival Corporation, the cruise line operator, in perhaps the worst moments of the crisis at the start of April.

In times of stress, most large banks have the same credit and risk appetite. But this was a deal depending on the issuance of stock at the riskiest end and on bonds secured against hard-to-value cruise ships at the supposedly less risky end, which few of its rivals thought possible.

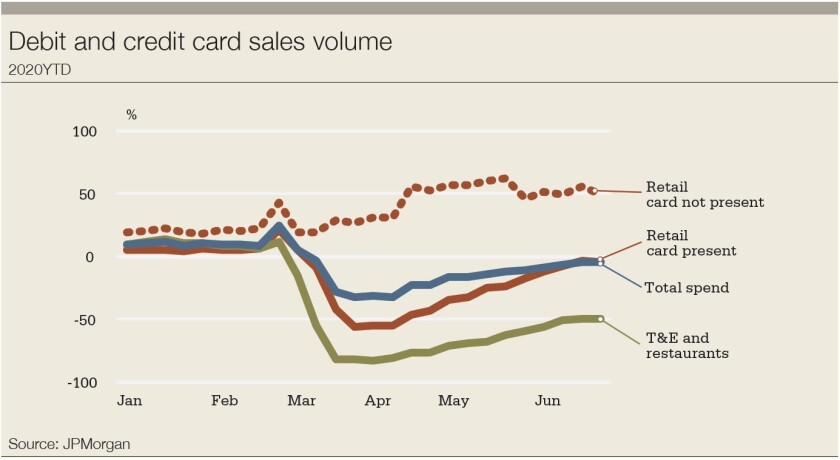

Credit and debit card data showed US spending on cruises to have fallen at the start of April by 100% compared to one year earlier. And there was no prospect of a quick turnaround. It hadn’t improved by the start of August. If anything, it had got even worse.

JPMorgan was lead left on $4 billion of first-priority senior secured notes yielding 11.9%, which made it the largest high-yield financing since the start of the pandemic. It was also lead left on the crucial $500 million issue of common stock and stabilization agent for $1.75 billion of convertibles.

After pre-marketing to key accounts, the deal was executed over two days with the bank playing off high-yield, convertible and stock buyers in the US and Europe, slightly increasing the overall size of the deal while tightening pricing from initial guidance.

These were welcome refinements. But it was essential for the company just to get the deal done as bookings collapsed, revenue dried up and its global fleet operations paused. JPMorgan’s entire capital markets franchise came together to deliver a mission-critical financing for a troubled client in the most turbulent market conditions since the financial crisis.

Its ability to do this is the third reason why JPMorgan is our world’s best bank for this extraordinary year.

Was structuring and executing deals such as the $6.25 billion package for Carnival Corporation all down to muscle memory from those crisis days back in 2008 and 2009?

“No. It’s what we do every day,” says Pinto. “You are always looking to help optimize clients’ balance sheets and raise the right amount of money at the best price, given the assets they have to pledge, if they need to pledge them.”

For a brief period, sources at most banks report, treasurers and CFOs still expected to obtain financing on the same easy terms as in the recent past. But discovering that you must raise whatever funding you can on the terms you have to offer or risk going under concentrates the mind.

“The discussions with CFOs and treasurers became quite rational very quickly,” says Pinto.

In late April, JPMorgan led another record deal for a troubled corporation, structuring the largest-ever debt financing package and leading the largest single-tranche bond for an airline, a $5 billion financing for Delta Air Lines that was increased from $3 billion after generating a strong order book from 350 investors.

The package included a $1.5 billion term loan B and $3.5 billion of bonds secured against landing slots. As well as leading the bond, JPMorgan also acted as ratings adviser to the company with which it has a long-standing relationship.

“If you think back to the aftermath of 9/11, it took between three and four years for airline travel to normalize,” says Pinto. “This time it may well be the same before people are happy to fly as they once did, although we can always hope for good news soon on a vaccine.”

JPMorgan was an active bookrunner on Boeing’s $25 billion bond deal at the end of April, coming after its first-quarter results and the announcement of the termination of its joint venture with Embraer. JPMorgan had been a lead on the company’s previous visit to the bond markets in July 2019 for $5.5 billion.

This was a very different deal with the company seeking liquidity across maturities from three years to 40 years, initially suggesting a $10 billion transaction and offering new issue concessions to get it. The order book built to $74 billion and the company raised $25 billion.

“That was the biggest-ever bond deal not related to an M&A situation,” Pinto points out.

Revolving credit facilities

By the end of the first half of 2020, investment grade bond markets had provided double the volume they saw in the whole of 2019. Companies were restoring their revolving credit facilities to emergency backup lines.

“A lot of that early lending has already been repaid because we were able to take companies to the capital markets for more sustainable financing as soon as they reopened,” says Pinto. “Some companies decided they didn’t need to fully use their revolvers after all.”

At the end of the second quarter, the bank’s loan balances had actually fallen by 4%.

We were supplying the market with liquidity when volatility became exteme, and for a while it did become extremely difficult to sell or buy

Was JPMorgan just a beneficiary as the Federal Reserve saved the banks by supporting the bond markets?

“Banks came into this in a very strong position,” says Pinto. “What happened on the secondary markets side was probably more interesting. We had discussed for years the issue of illiquidity and whether in a time of stress it would even be possible to sell or buy securities, given the mismatch between the buy side’s enormous positions and the amount of sell-side capital available for intermediation.

“We were supplying the market with liquidity when volatility became extreme and for a while it did indeed become extremely difficult to sell or buy.”

Leading bank dealers had to process extraordinary volumes three or four times above normal market conditions.

“It was central bank support that allowed markets to function,” says Pinto. “The mere fact that these measures were there restored confidence. We were then able to handle volumes that were many times greater than what we had seen during the various mini-corrections throughout the long bull market that followed the financial crisis.”

Pinto’s view is that: “If the central banks had not intervened, banks would still have been OK. But asset managers would likely have faced massive redemptions from investors, which they would not have been able to meet by selling securities into declining markets with asset prices in freefall. Within a couple of weeks, central banks implemented measures that had taken two years to deliver during the last crisis.”

The bank did not deliver only through the capital markets.

Hotels were as hard hit as airlines and cruise operators. In April, JPMorgan was an active bookrunner on a $1.6 billion, five-year senior unsecured bond for Marriott International that helped it to hold off the risk of imminent downgrade. The company has eased the leverage covenants on its $4.5 billion revolving credit facility, although doing so required it to add different covenants, including on maintaining minimum liquidity.

It had to take out a new 364-day revolving credit facility to achieve this. But it quickly refinanced through the five-year bond.

Then in May, Marriott signed amendments to its co-brand credit card agreements with JPMorgan Chase and American Express, which provided the company with $920 million of cash, fully $570 million of it coming from Chase.

That included $500 million of prepayment of certain future revenues and $70 million from the early payment of a previously committed signing bonus under the co-brand credit card agreement. Marriott was able to record the cash as deferred revenue, which would be available for general corporate purposes.

It’s essentially a bet on travel picking up again.

At an investor conference in May, Dimon explained the bank’s thinking on the Marriott deal in simple terms: “They needed some help. We asked for a bunch of things in there, they’ve been an absolutely outstanding partner and we’re hoping this turns out well for both of us.”

Small businesses

Away from such deals for large corporations, JPMorgan also stepped up for small US businesses. It played a key role working with the Small Business Administration (SBA) through the first two phases of the payment protection programme (PPP), which was designed to extend modest and forgivable loans to small business so that they could avoid laying off staff.

We got an awful lot of money to a lot of small businesses

The programme has attracted criticism for sending funds to larger companies that used them for general corporate purposes.

JPMorgan worked hard to get them to their intended recipients. But it wasn’t easy.

Gordon Smith, chief executive of consumer and community banking, tried to explain at a Morgan Stanley conference in June.

“Although it was a tough start, we were building the product as it was announced. But partnering with the Small Business Administration, partnering with Treasury, we, I think, got an awful lot of money to a lot of small businesses – actually quite quickly,” he said.

“We all read about a number of complaints industry-wide for small businesses who are looking for money. It took about 10 to 12 days to build the technology.”

Updating the numbers in August, Brent Reinhard, chief marketing officer for business banking at Chase, tells Euromoney: “We are the number one payment protection programme originator by loan amount, having disbursed $31 billion to 275,000 of our business customers. That has helped to support more than three million jobs.”

Reinhard says it is a myth that the money went to large corporations. “Fifty percent of our loans went to companies with fewer than five employees and 60% of loans were for less than $50,000.”

We are the number one PPP originator by loan amount. That has helped to support more than three million jobs

Mid-cap

In between helping big companies like Boeing and Delta Air Lines, and small businesses served through Chase’s US branch network, JPMorgan also took strides through the pandemic to do more for larger mid-cap companies inside and outside the US.

The commercial bank had already identified local corporations headquartered in Europe and Asia as a growth opportunity and decided that if the corporate and investment bank served the largest 3,000 companies in the world, it was important to do more for the next tier down. In February 2019, the commercial bank appointed CIB veteran Andrew Kresse to run corporate client banking and specialized industries (CCBSI) internationally, reporting to CCBSI head Rob Holmes.

At the bank’s investor day in February, Doug Petno, head of commercial banking, said the firm had identified 1,200 such international prospects.

Kresse tells Euromoney: “JPMorgan is not new to these countries, having been present in many in Europe and Asia for 100 years or more, so these clients are typically not new to the bank. It’s more that they may have used us for just one product: wholesale payments, say, or cash management.

“Client selection is everything. In identifying these prospects, we are not narrowly focused on any single measure such as annual turnover. Rather, we are focusing on the needs of companies operating internationally that may use more of the services of a global bank with a diverse range of products. That, after all, is what differentiates us,” he says.

“Outside the US, clients don’t think of us as their US bank. We are working with German companies, for example, that want help with cash management in India.”

Outside the US, clients don’t think of us as their US bank

The traditional approach to corporate banking for the handful of global banks like JPMorgan that have all the products in all the geographies is to lend first and then chase every bit of ancillary business – FX hedging, outsourced treasury, capital markets. Having already built the product machines, the cost to serve is low. The machine just needs throughput.

“If you asked me pre-Covid how we secured relationships with such companies, I would have said often through lending, also through payments and transaction services,” says Kresse. “What we found through the crisis was that the companies we wanted to work with didn’t need more lending, as increasing their credit exposure isn’t necessarily the solution for many. Most banks have the appetite and capacity to support creditworthy borrowers today and government resources were mobilized to provide credit. What some companies didn’t have was capital markets distribution to a globally-diverse base of debt and equity investors.”

Kresse points to deals such as the €340 million debut high-yield issue JPMorgan led in June for German company Profine, an owner-managed manufacturer of PVC windows, doors and shutters that employs approximately 3,000 people at 29 sites in 22 countries.

The five-year deal was central to the company’s efforts to refinance its credit facilities coming due at the end of this year.

Also, in June, JPMorgan led a €274.7 million term loan B to provide acquisition financing for French medical testing company BioGroup, which runs 600 laboratories in the country. In March, at the height of the Covid pandemic, BioGroup had to delay the deal to finance the purchase of Laborizon, which brings 106 sites across France.

“These mid-cap companies are now exploring new investor bases,” says Kresse. “We are prepared to lend, if that is what clients need. We have a fortress balance sheet. We prepare for the worst and we want to be there in times of need. JPMorgan’s commercial banking business’ balance sheet is over $200 billion. But around the world, banks are lending aggressively at low rates today.

“What clients are looking for now are new ways to extend tenors and diversify their investor bases. As a firm, we can pivot to providing that, not just through debt capital markets but also convertible bonds and equity capital markets.”

It remains to be seen how well JPMorgan’s credit underwriting standards have set up that fortress balance sheet to cope with whatever credit impairments emerge in the quarters to come. Lost beside that $8.9 billion reserve build for the second quarter was a $678 million gain from writing back bridge commitments that had been marked down in the first quarter.

The financial markets are a little optimistic and appear to be pricing in an outcome better than our base case. But the chances of Armageddon are low

That was another side benefit of the capital markets boom that helped the CIB produce a 27% return on equity in the second quarter, while consumer and community banking recorded a $176 million loss.

The bank said back in July that 7.4% of all auto loans were subject to payment deferrals, as were 6.9% of all home loans, 4% of business cards and 2.1% of consumer credit cards. And while in most categories half of those customers have made at least one payment during the deferral period, over 90% were already 30 days overdue when deferrals were granted.

Record trading volumes, wide margins and booming new issues won’t provide the same bounty in the quarters to come. Dimon told analysts on the second quarter conference call to model just 50% of what came in during the initial markets recovery.

Did JPMorgan take big reserves in that quarter because it could afford to?

“The biggest portion of reserves have gone against credit cards,” says Pinto. “Given the quality of the portfolio we have, I don’t think they will convert into losses of that size. I do think the financial markets are a little optimistic and appear to be pricing in an outcome better than our base case. But I think the chances of Armageddon are quite low.”

What other key lessons has the bank learned?

“The good news is that we had no issues at all in processing huge volumes in payments, lending, capital markets, securities services. When we transitioned to working from home in mid-March – and at one point that was 95% of all staff – we couldn’t be sure how that would play out. It worked far better than I imagined,” says Pinto.

“This bank has spent an awful lot of money on technology. It now turns out that every penny was well spent. We should be wary of extrapolating from all this that having everyone working from home all the time is sustainable. Productivity may go down. Personal interaction is very important, for networking, for innovation, developing junior staff. However, it probably won’t be necessary to have everyone back in the office all at the same time,” he adds.

“We have always thought it was vital to invest in technology infrastructure – and that will be even more of a priority in future.”