A new study backed by Singapore’s powerful sovereign wealth vehicle Temasek has painted a troubling picture of the economic cost of biodiversity and nature loss – and made a case for a big investment opportunity in taking a different course.

'New nature economy: Asia’s next wave' was launched by Temasek alongside AlphaBeta, a strategy and economic advisory business headquartered in Singapore, and the World Economic Forum at the end of September.

Among its headline findings are that 63% of Asia’s GDP, or $19.5 trillion of economic activity, is threatened by biodiversity and nature loss. In addition, up to 42% of all species in southeast Asia could be lost, half of them representing global extinctions; and that of the 100 cities considered to be facing the most pressing environmental risks in the world, 99 of them are in Asia.

Set against that, the report also argues there are opportunities to unlock $4.3 trillion in business value and create 232 million jobs annually in the Asia-Pacific region by 2030 by following nature-positive business opportunities. This would require $1.1 trillion of investment annually: an enormous amount but, the authors note, far less than the $31.1 trillion announced by Asian Development Bank member countries to combat Covid-19.

Nature positive

The idea of nature-positive business models has entered the mainstream of ESG parlance in recent years as a different course to purely seeking to reduce carbon. It will be a key part of discussions at the COP26 meeting in Glasgow.

Being nature-positive means adding natural capital back to nature, which might involve investments in areas such as agro-forestry, natural water supply or mine rehabilitation; or taking actions that reduce impacts on nature. This could include reducing material demand, using alternative proteins, or improving energy efficiency in the built environment.

“Tackling climate change is crucial,” says Fraser Thompson, founder and managing director of AlphaBeta. “But it is not enough. We need to add on other elements to tackle nature loss.”

A lot of the challenges we see, especially at the grassroots level, are really about the bankability of projects

So, for example, solar energy is an indisputably good thing in climate terms.

“Solar is incredibly important but it can take up three to 12 times the amount of land that a coal plant can," says Thompson. "If we’re winning the carbon battle but we’re losing the nature battle… we think a nature lens is something additive to just the climate discussion.”

Clearly the two are linked: climate change is responsible for between 11% and 16% of nature loss, according to the IPBES Global Assessment Report, an earlier study. But increasingly, biodiversity is being considered as a separate theme in ESG.

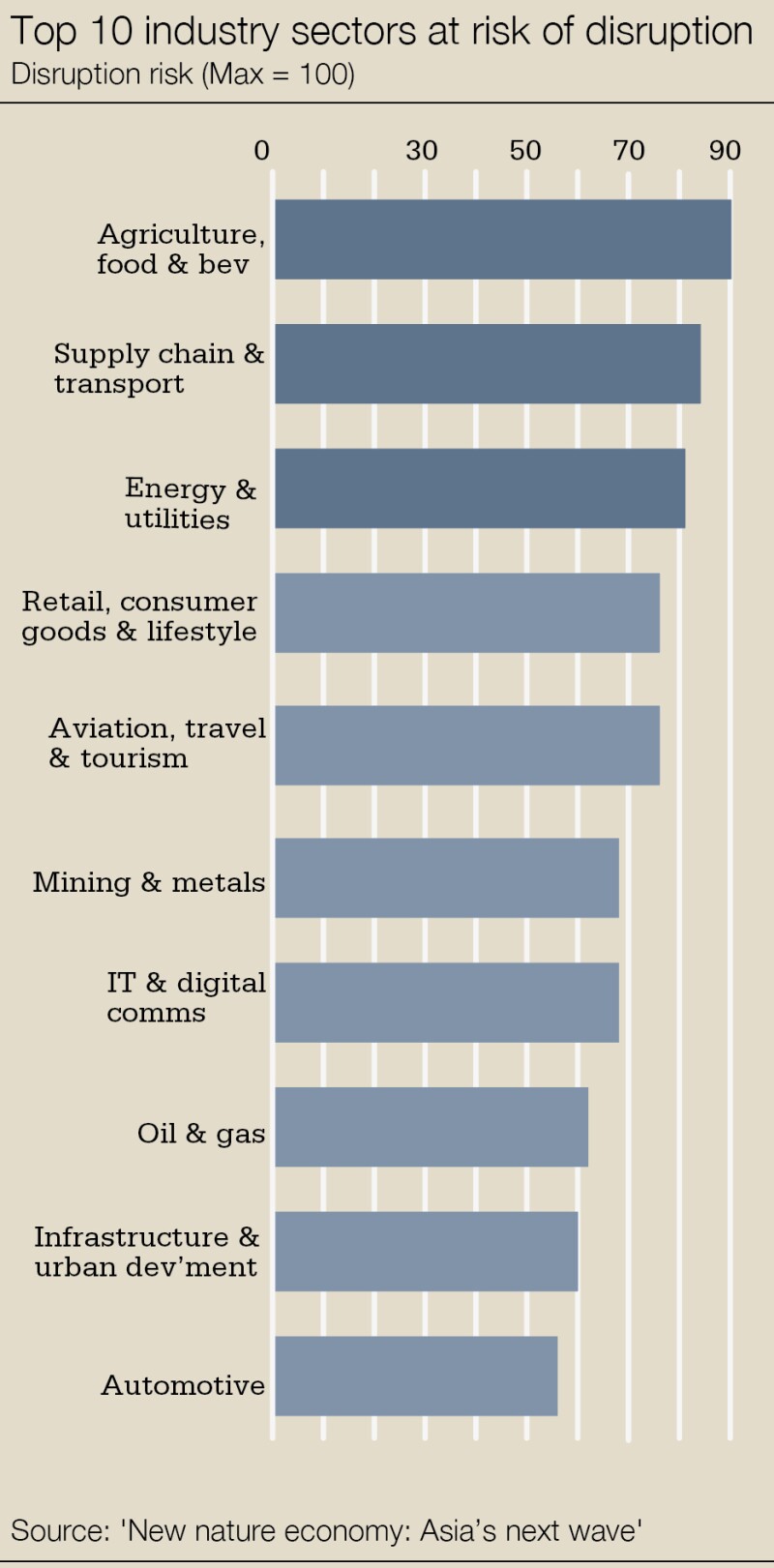

And Asia is considered especially vulnerable because of the higher economic contribution of sectors that are at risk of disruption from biodiversity and nature loss: agriculture, for example, and extractive industries, as well as downstream manufacturing industries that rely on extracted resources.

Statistical examples are everywhere. Asia Pacific accounts for 35% of global agricultural land and 45% of global agricultural emissions; there are over 60,000 abandoned mines in Australia accounting for hundreds of thousands of hectares of degraded land; over 70% of fish stocks in the Philippines are fished beyond sustainable levels; Apac accounts for more than half of global food waste; Apac has eight of the top 10 countries responsible for marine plastic pollution; Asia is the most water-stressed continent of all; and China’s Belt and Road Initiative overlaps with the habitats of 265 threatened species.

“A business-as-usual route that disregards our economy’s impact on biodiversity and nature loss is therefore not a viable option,” the report says. “As important as it is to decarbonize the economy, it is not enough if the other direct drivers of biodiversity and nature loss are not tackled concurrently.”

The report argues the case for 59 nature-positive business opportunities. They include $1.6 trillion of opportunities in the food, land and ocean use system, $1.2 trillion in infrastructure and built environment, and $1.4 trillion in energy and extractive industries.

Practical examples of these include the expansion of nature-positive renewables, increasing energy efficiency in buildings, and reducing food waste. To take the last of these as an example, the report says that up to 70% of all food waste occurs in the value chain before reaching consumers, and that reducing food loss and waste in the supply chain could generate cost savings of $233 billion in 2030 in Apac, and $87 billion in China alone. Examples of innovation include the development of off-grid cold storage solutions in India, with the refrigeration driven by solar power.

Bankability

But what’s stopping money getting where it needs to go?

“A lot of the challenges we see, especially at the grassroots level, are really about the bankability of projects,” says Frederick Teo, managing director of sustainable solutions at Temasek. “It is not about the lack of availability of capital. That often is not the problem. There are pools of capital ready to be deployed.

“The question is about finding these projects and preparing them to make them bankable.”

Making things bankable requires several techniques.

“Local partnerships are key, because many of these things require an understanding of the local context,” says Teo.

If carbon projects can be site-specific and very diverse in their challenges, nature-based solutions are arguably even more so: no two projects are alike.

It is commonly said that projects need to get up to scale in order to attract institutional capital, and this is broadly true, but Teo says there is more nuance to this point.

“I would argue that in some cases, the size of projects can actually be smaller, because you can access different pools of capital,” he says.

The challenge in biodiversity is that there’s often multiple market failures. So, it is not enough to tackle just one of them

He gives an example of new technologies allowing backers to cost-effectively electrify a small village with solar and batteries without ever having to hook up to a national grid, a smaller level of investment than would previously have been required.

“That means a particular pilot project to bring electricity there could be had at a much lower level of capex compared to what you might have required in the past," says Teo. “So, the idea now is that you can crowd in new kinds of capital and lower the barriers to entry to be able to make real change on the ground. But it doesn’t remove the fact that you need to have some local partners that are aware of this need, to be able to size this need and develop a business plan that can allow such a project to viably continue.”

Other barriers the report highlights include insufficient pricing of externalities, entrenched behaviours and a lack of harmonized biodiversity reporting standards.

“If you look at a lot of innovations that happen, they are about finding a way to get around a market failure,” says Thompson.

That might be around a change in consumer behaviour, a new way to mobilize capital, or a technological step forward.

“The challenge in biodiversity is that there’s often multiple market failures. So, it is not enough to tackle just one of them. You’ve got to tackle the next one, and the next one.”

To take the earlier example of solar-powered food cold storage, that can be expensive and capital intensive. Also, the improvement at that end may be impeded by continuing bottlenecks elsewhere in the chain, such as in processing.

The answer is to bring in capital that backs integrated solutions and looks at the whole chain from end-to-end to understand where the investment is needed.

Thompson says: “If we can start to chip away at some of these barriers through different solutions, it then makes it a lot easier for entrepreneurs to get into the space, because they’re only having to tackle one market failure rather than three or four to get something off the ground.”

Win-win

Moving towards new solutions can be a perilous task in Asia, where the population is so large and so many are either in poverty or vulnerable to it. Any new system has to bring a whole community along with it without imperilling any of their livelihoods along the way.

Thompson says: “It is obviously a crucial issue, but in the vast majority of these cases, there is a clear win-win.”

Where trade-offs occur, it is when outdated nature-destructive models are replaced by something better, which can have an impact on labour, particularly in agriculture.

One thing all players in this space would like to see is harmony of standards.

“When we finally have a harmonized global standard on decarbonization, we will begin to realize that different pathways of doing things have a very different net carbon abatement potential,” says Teo. “The regulatory and policy framework has to be clear.”

Thompson adds that “a lot of the standards we have are not coordinated and consistent, and that leads to challenges for businesses in terms of compliance costs, and means investors don’t get the information they need on a comparable basis.”