Euromoney sits down with Noel Quinn in an industrial park in Singapore. There’s more significance in this than you might imagine, and not just because the event his arrival coincides with – Bloomberg’s New Economy Forum – is the first attempt at a landmark real-world conference in Asia for the best part of two years.

HSBC chief executives normally hold interviews in one of two places, 8 Canada Square in London or 1 Queen’s Road Central in Hong Kong. These are the bank’s two homes, one official, one spiritual – the latter being the one where most of the money is made.

In fact, the weight that Hong Kong holds in the generation of profits at HSBC is such that the rest of Asia, mainland China notwithstanding, can feel like an afterthought.

Euromoney argued in February, after the bank’s latest pivot to Asia strategic announcement, that “for much of the past 20 years, ‘Asia’, in HSBC parlance, has really been a shorthand for Greater China.”

It’s about Hong Kong, China and the rest of Asia. I want growth on all fronts. I’m investing to get that growth to become reality

It was partly in response to that article that Quinn met us in Singapore. The Asia that he envisages is the whole thing: not a reduction of Hong Kong’s importance by any means but a southeast Asian and Indian operation that can stand reasonable comparison as an engine of growth and profitability.

“It’s not a case of Hong Kong or rest of Asia,” he says. “And this is the key message. It’s about Hong Kong, China and the rest of Asia. I want growth on all fronts. I’m investing to get that growth to become reality.”

That is true. In that February announcement alongside the 2020 full-year results, Quinn pledged that about $6 billion would be invested in Asia and that capital allocation to Asia (measured as a percentage of group tangible equity) would climb from 42% to 50% in the medium to long term.

He apportioned that money on two metrics. By business, he said, the money would be split $3.5 billion to wealth and personal banking, $1.7 billion to corporate banking and $800 million to global banking and markets in the region.

Another statistic, less remarked upon, was that roughly half of the $6 billion would go to Greater China and half to the rest of Asia.

This was important because doing it 50/50 is not a reflection of how HSBC’s Asia income works today. Hong Kong alone is usually more than half of Asia profits and sometimes much more; in the first half of 2020, for example, it was 68% of regional profit before tax, and for the whole of 2020 it delivered more than twice as much adjusted revenue as India, Singapore and Mainland China combined. Include the Greater Bay Area, which has been the central focus of the bank’s mainland ambition in recent years, and the dominance of that small geographical piece of Asia is starker still.

Show of intent

Numbers like these bounce around a bit in an environment of Covid-related capital charges and releases. In the 2020 full year, for example, Asia accounted for 146% of group profits, which is to say, more than the entire group itself made. A more durable indication is that Asia accounted for 51.2% of global revenue in the first half of 2021 and that Hong Kong was 58.3% of that. Whichever way you cut it, Greater China is so important to HSBC that putting half of a new multi-billion dollar investment commitment into the rest of Asia is a show of intent.

“We are a global bank,” Quinn says. “But we also know our core strengths, our heritage. And a huge amount of opportunity lies in Asia.

“Everybody knows we’re extremely strong in Hong Kong. We’re also the biggest international bank in China. We’ve had good growth over recent years in both of those markets, and we want to continue to grow there.

“But we’re also spread throughout Asia, and we have a strong base here in Singapore. I want growth and I see opportunity for growth in the rest of Asia as well, including India.”

So how is this pivot to Asia different to the past?

“If you look at our past investment programmes, they tend to have been pretty much focused fully on growing in Hong Kong, Greater China and within China it’s tended to be the Greater Bay Area,” says Quinn. Within that, much of the Greater Bay Area investment was around retail banking.

This time, he says, the China investment is around wealth management, as it is for the rest of Asia, where the focus previously tended to be more heavily on corporate banking. Wealth, in the HSBC definition following a February 2020 combination of businesses under the wealth and personal banking unit, means mass-affluent, asset management, insurance and private banking.

“This time, I’m looking for a much more balanced growth portfolio and growth opportunity going forward than we’ve had in the past,” he says. “We’re leveraging off our heritage of over 150 years. And we’re also trying to say to clients in Asia: ‘If you want to tap into the global network of HSBC and for us to take you into the rest of the world, we can do that.’”

This all makes sense intuitively: Euromoney has argued before that HSBC has not made enough of that heritage outside Greater China, where its offices are often in iconic buildings from Mumbai’s Fort district to Singapore’s Collyer Quay, part of the fabric of those countries’ financial history. So, it’s good that it’s being prioritized once again.

But with wealth the principal recipient of investment, it’s easier said than done to build a leading private banking business in Singapore, where so many houses claim to have top five regional ambitions that it has become something of a running industry joke. What’s the differentiator for HSBC?

“Well, we’re doing it from a position of strength,” says Quinn.

“We’ve already got a strong wealth franchise in Hong Kong, and we’re already known as an international private bank, so we’re not doing it from a blank sheet of paper.”

Strength

In asset terms, benchmark surveys tend to put HSBC as a top-five name in Asia, in the chasing pack behind the Swiss leaders. Asian Private Banker, for example, ranked it third by assets under management in 2020 with $176 billion, and first for wealth management client assets across retail and private banking, with $488 billion. In Euromoney’s 2021 private banking survey, HSBC ranked seventh in Asia for overall private banking services, fifth for high net-worth clients, sixth for ultra-high net-worth and third for environmental, social and governance/impact investing.

The bank already has strength in wealth in Greater China and is growing both organically and through its investment in Pinnacle, the Trista Sun-led Shanghai fintech that arms thousands of financial planners with digital tools (but no branches) to reach out to wealthy potential clients. HSBC’s third-quarter results presentation showed 450 Pinnacle planners in force. China’s Wealth Management Connect scheme should help further.

“Now I want a stronger product and distribution capability in southeast Asia and in India,” says Quinn.

Doing so is likely to involve acquisition. Indeed, it already has. In August, HSBC bought Axa Singapore for $575 million, although that is more an insurance play than a book of private-banking business. Nevertheless, insurance is part of wealth at HSBC and Axa brings with it a large tied-agency sales force. Both Quinn and Nuno Matos, head of wealth and personal banking, presented the deal at the time as a sign of commitment to wealth management.

“We think that accelerates our investment programme by three to four years,” Quinn says of the Axa deal. “It builds out distribution capability and product capabilities, adding to what we already had in Singapore. And the two together is more powerful than just building organically over the next three to four years. It accelerates that plan.”

So what I have, that many of my competitors don’t have, is that heritage of corporate banking for 150 years

On further deals, he says: “I’m looking at three to four more acquisitions in Asia, that similar type of bolt-on. That could accelerate the growth plan for us.”

The challenge here will be availability. Following a period when a slew of non-core businesses were sold by global players to Singaporeans and Swiss pure-plays (Barclays to OCBC and Bank of Singapore, Societe Generale and ANZ to DBS, Merrill Lynch to Julius Baer), there are fewer of those books around.

Quinn argues that another strength is the breadth of HSBC’s existing customer franchise in Asia. In the last 12 months, he says, about 60% of the net new money in the private bank in Asia came from wholesale customers.

“So, what I have, that many of my competitors don’t have, is that heritage of corporate banking for 150 years,” business owners who “are natural targets and natural opportunities for our wealth management propositions. And on the evidence of the last 12 months, that’s attractive.

“Now I think we’ve underplayed that in the past, we’ve under-penetrated that opportunity.”

Some early numbers show the strategy making progress: third-quarter results, reported in October, showed that the Global Private Banking unit in Asia had $182.5 billion under management, up 11% year on year, and that of $3.9 billion net new money in private banking globally, $3.1 billion was in Asia.

Growing further is going to need more people and here is a challenge. If you were looking for a career to send your kids into in these uncertain times, you could scarcely do better than urging them to be a relationship manager in a Singapore private-wealth business. They are in quite extraordinary demand.

Against this backdrop Quinn says the bank has grown its HSBC Singapore headcount by 10% “over the last few years,” as well as bringing 600 people into wealth management in China in the year to date (wealth chief Matos has said it will end 2021 with around 700). “We’re on track to do our target of recruitment this year. So, it is difficult? Is it competitive? Yes. Are we able to achieve the targets we’ve set ourselves on recruitment? Yes.”

Hires

HSBC has sought to send a message to Asia with some of its personnel decisions. In 2021 it has shipped four global business heads – Barry O’Byrne, head of global commercial banking; Greg Guyett, co-head of global banking and markets; Nicolas Moreau, head of global asset management; and Matos, head of wealth and personal banking – from the UK to Asia.

But it’s worth noting that all four were sent to Hong Kong. Then, when veteran Peter Wong retired as overall Asia-Pacific chief executive, he was replaced by two co-heads, David Liao and Surendra Rosha. Rosha, the former head of India, was a telling representation at the top for someone who made his name outside Greater China. But both are still based in Hong Kong.

Senior hires have taken place in Singapore over the last 18 months, including Edward Lee as regional head of equity capital markets for southeast Asia, Kee Joo Wong as HSBC Singapore chief executive and Stuart Lea as head of global banking coverage for south Asia. But probably the only example of a function that might ordinarily have been in Hong Kong going to southeast Asia came just the day before our interview. Then, Stuart Tait was replaced as head of the commercial banking business in Asia Pacific by two people: Frank Fang in Hong Kong and Amanda Murphy, who will relocate from the UK to Singapore.

At Citi, the obvious comparison with HSBC, the regional head of markets, co-head of Citi Global Wealth, vice-chair of Asia Pacific corporate banking and the head of the global consumer bank for Asia are all based outside Hong Kong in Singapore and Taiwan.

“You’ve got to remember our regional head office of banking operations in Asia is based in Hong Kong,” says Quinn. “The four roles I relocated were global roles. So it’s right they are located in Hong Kong. They have a global brief, they’re not just Asia.”

But he says Murphy in Singapore “will have the mandate to go and drive opportunity across all of the rest of Asia, including India, to try to drive revenue synergies, drive collaboration and have a greater presence with clients. And I think that’s an important development.”

The job in question is Quinn’s old role, or half of it. He ran commercial banking in Asia from 2011 to 2016, looking after 22 markets and spending three weeks a month on the road visiting them in the time-honoured HSBC commercial banking style.

“If I want to be true to the growth ambition," Quinn says, "what I’ve done in the announcement yesterday is to bring focus so that we can grow not only in Greater China but the rest of Asia through focus, by having people on the ground.”

If it’s not yet the most senior people, there are other signs of grassroots expansion in south and southeast Asia. In Malaysia, for example, a new head office is due to open in March within the new TRX development in Kuala Lumpur, wholly owned by HSBC and at the cost of RM1 billion ($239.2 million). The bank has spent $58 million there building its digital capability since 2018.

In Thailand it launched private banking in February, and in Indonesia and Vietnam the bank has been involved in a string of deals and sustainable landmarks all year, from green deposits for corporate clients and an exchangeable sustainable bond for Vinpearl in Vietnam, to financings for geothermal energy, vaccine suppliers and a public-private partnership telecom satellite in Indonesia.

Green financing is increasingly a bridgehead for the bank, particularly in Australia, where deals for Worley and Woolworths have been landmarks. And the bank has taken in $400 million of green deposits in a year in India, while handling eight of the 10 green-bond issuances there in 2021 and completing blockchain-enabled trade finance transactions for ArcelorMittal Nippon Steel.

India

Which brings us to India.

Any bank seeking to grow in Asia beyond Greater China needs to make a call on India, which has been something of a graveyard for foreign banks, particularly on the investment banking side where fees are not so much tight as excruciating.

HSBC is bigger here than some realize, earning $3 billion of adjusted revenue in 2020 with 20% growth in the wholesale banking arm that year. The key here, Quinn says, is focus.

“Be realistic, we can’t compete as a domestic SME [small and medium-sized enterprise] bank or, in some cases, for pure domestic mid-market corporates in India,” he says.

When he ran Asia, he told his teams in India to “find our niche. And our niche, as a wholesale bank in India, is really to help our Indian clients access the rest of the world and our clients from the rest of the world access India.

“It’s very easy in India to get huge growth, make a few mistakes, have to retrench and then try to rebuild,” he says. “It’s peaks and troughs.”

He says he told his bankers: “I know you can do 30% and 40% per annum growth. But let’s do 10%, 15%, 20%. Let’s do that consistently every year and you’ll double your business every five years or so.”

What about wealth? Will HSBC’s ambition stretch to this highly competitive market? Quinn says it does and that he is looking at how to enhance that offering, although under the broader definition of wealth that includes insurance, investment products and asset management. He thinks premier banking is a differentiator in India. More broadly across Asia, he says onshore services will make sense in some disciplines.

That’s a message for me: if you stay focused on your customers and their needs, they still need international banking services

As we speak, Citi is in the process of exiting retail markets across Asia and the Middle East, seeking to dispense with relatively low-return business in order to deploy the capital in wealth and institutional. Citi, generally, is a much more diversified operation in Asia than HSBC and will remain so even after these sales; it has no dominant franchise.

Is there logic in Citi’s divestment strategy for HSBC?

“Well, we’ve already, over the past five to eight years, trimmed our retail operation substantially,” Quinn says. Stuart Gulliver and then John Flint exited about 100 businesses and geographies worldwide. Quinn is quitting two more – “two legacy markets that needed resolution” – retail in France and mass-market retail in the US.

“I think in Asia we’ve already got a very focused retail presence,” he says. It is clearly enormous in Hong Kong and then in China and Singapore tightly focused on international wealth customers. “So, I feel comfortable with our current footprint in retail banking. You always look at your portfolio. But materially, the heavy lifting has been done.”

How about investment banking? There is a familiar pattern here: utterly dominant in Hong Kong debt, strong in China and weaker further afield. Quinn says debt is clearly “a core strength”, as is foreign exchange, but he also makes a case for the bank’s advisory and equity capital markets capability in Asia, “particularly mid-market clients.”

According to data from Dealogic, in the year to November 17, HSBC was the number-one house for ex-Japan Asia G3 debt capital markets. It is the undisputed leader for sustainable bonds in the region – Jonathan Drew and his team have won Euromoney’s sustainable finance award in Asia four years in a row – and ranks fourth in loans. But it ranked 14th in ECM and 13th in M&A.

Quinn says the bank is “investing in the global banking and markets business, building out sector expertise and product capability and enhancing the proposition. We have a hugely attractive client base upon which to offer those services.”

Impossible positions

In the background to Quinn’s mission to diversify, one can’t ignore the fact that Hong Kong is a very different proposition to what it once was, and that HSBC in particular has suffered from this.

The bank is caught in an awkward position, even an impossible one. It must stand with its customers in Hong Kong while not antagonizing China or indeed Hong Kong’s own government. It must meet the expectations of Western investors on governance, while dealing with a highly divisive National Security Law in Hong Kong.

Things are not quite as difficult as during the Huawei furore or when HSBC was still under a US Department of Justice (DoJ) deferred prosecution agreement (that expired in January 2021), which led the place to be filled with DoJ appointees; but Hong Kong is still a very hard place to try to keep every stakeholder happy.

When Euromoney asks if this creates an imperative to diversify away from Hong Kong, Quinn stands up for the place.

“No. It’s an imperative, first and foremost, to help our colleagues and our customers in Hong Kong,” he says. “Hong Kong has been extremely good to HSBC for 156 years.

“Times are tougher today with Covid, with the social unrest before Covid and with the geopolitics, so my primary focus is helping Hong Kong navigate that difficulty, helping our colleagues and customers through what is a very difficult economic downturn.”

I’m pleased with the position we have on commercial real estate in China. We’re feeling we’re in a good position

He reiterates that his strategy is not at the expense of Hong Kong but additional to it.

“I want that exact same story in Singapore, in India, across southeast Asia. So, one could argue we’re fighting and seeking opportunity on four fronts: continued growth in Hong Kong, continued growth in China and accelerated growth in Singapore as a primary base for Asean, and in India.”

A great deal of the geopolitical and social situation around Hong Kong and China is beyond HSBC’s control. It simply cannot be fixed and it is not going away. HSBC can’t stop bilateral trade wars, a pandemic or a riot. But it has to deal with all of them. How does it manage in such an environment?

“You stay focused on what you can control. And what you can control is your business and how you’re serving your clients. Then the other thing you can do is share your story with key stakeholders. That is what we’re doing.”

It is impossible to ignore the politics, but Quinn is realistic: “I’m not here to make political judgments or political statements. That’s not my role.

“We’re an international bank and have been for 156 years. The world has gone through phases of difficult geopolitics in 156 years, one could argue much more difficult phases than the one we currently face. We’ve navigated them in the past.”

Besides, he says, the numbers can be surprising. 2020 was dismal for international banks with the combination of Covid and geopolitics. Yet Quinn says that the volume of commercial banking clients asking HSBC to help them bank in other countries beyond their home has gone up 15% in 2021.

“Now, you would never expect that statistic in a world that was slowing down dramatically, with geopolitical challenges,” he says. “But our customers are saying: ‘We still need help internationally, please help me navigate the change to my supply chain, help me navigate the uncertainty of the world.’

“That’s a message for me: if you stay focused on your customers and their needs, they still need international banking services.”

Exposure

It is encouraging that HSBC has come through Covid with asset quality in very good shape. This is true of all international banks to a surprising degree, but nevertheless there are a number of potential mis-steps that HSBC seems to have avoided.

This was most obviously the case with Evergrande and its knock-on effect on Chinese real estate. With its third-quarter numbers, HSBC published a breakdown of its China exposures showing that it had total drawn risk exposure of $194 billion in mainland China at the end of June, $183 billion of it wholesale and $19.6 billion of it to Chinese real estate if $4.9 billion of exposure through Hong Kong-incorporated property companies is included.

That’s eye watering, given what’s happened to the sector, but HSBC says that none of the exposure was to developers in the red category under China’s three red lines as of the end of September.

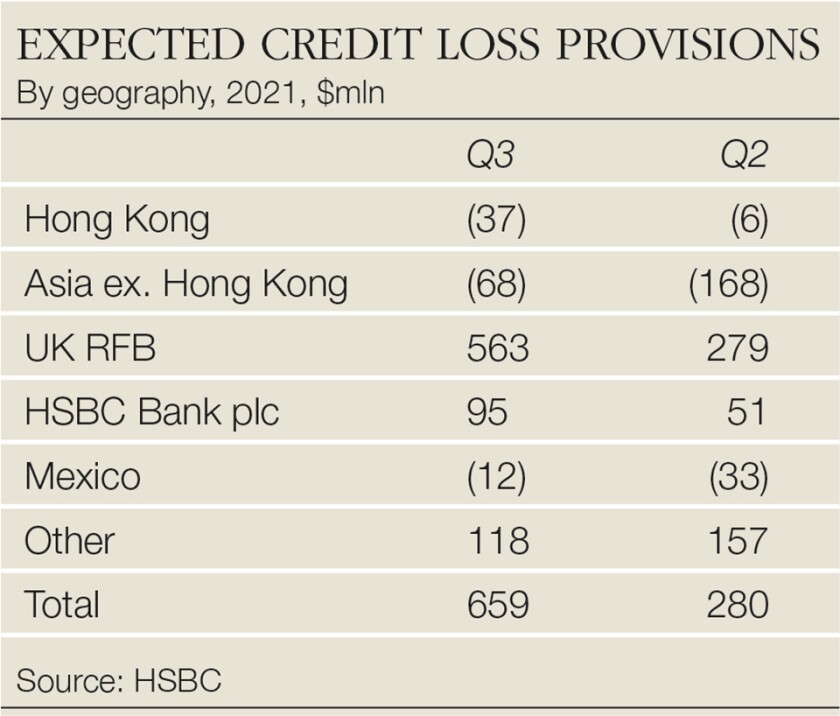

In fact, expected credit losses (ECLs) from China are still low. HSBC did announce some ECLs in Hong Kong ($37 million) and the rest of Asia ($68 million) in the third quarter, but they were inconsequential when at a group level HSBC released a net $659 million of charges, mainly from the UK ring-fenced bank.

Asked about risk management and credit quality, Quinn taps the table – touching wood – before attributing the performance to people: “I think it helps greatly to have people on the ground permanently, understanding the development of local markets and local economies.”

By way of illustration, he says that HSBC is in 60 cities in China, not just Beijing, Shanghai and Shenzhen. “That helps you stay close to the local corporates. That’s an important part of any due diligence.”

Overall, on Evergrande, he says: “I’m pleased with the position we have on commercial real estate in China. We’re feeling we’re in a good position.”

But he’s right to tap that table. Chinese credit quality is not a completed story and HSBC’s risk management skills will likely be tested in the months ahead.

Quinn is a calm, unflappable figure, speaking slowly and precisely in a light Birmingham accent. Unusually, he is widely liked, even by competitors; the phrase ‘down to earth’ is never far from any account of him.

The only time in our interview when he looks nonplussed is when we ask if HSBC’s brand and heritage, which he has mentioned at least half a dozen times by this point in the conversation, still matters to customers in Asia today.

At this he looks briefly perplexed at the very idea.

“It’s huge,” he says. “There is a strong affinity to the brand,” which he has seen all over Asia during his time based here.

“But you should never take it for granted. The most important thing in relationship banking is to be there in the not-so-good times, as well as the good times.”

He uses the example of the liquidity of the bank. He says that, relative to the start of Covid, the bank’s deposit base has gone up by over $200 billion.

“That in times of trouble, customers who have already deposited over $1.6 trillion with you deposit another $200 billion,” he says. “That’s a measure of the strength of the brand.”