As well as a deadly illness, Covid has also unleashed inflation into a world that does not know how to cope with it.

Diseases, like wars, create a shortage of labour. After years of decline, wages are picking up once more. So are the prices of energy, durable goods, housing and food. The spectre of inflation is darkening the outlook for investors everywhere as they search for a place to put their money and generate a real return in 2022.

Jump to:

Markets were calm in 2021 until the panic over Omicron gave a brief taste of what may be to come. Spreading across the buyside and the sellside is the uneasy sense of a long cycle coming to an end, with the big sell-offs soon to start.

Higher rates to fight inflation will hit everywhere. Real estate is supposed to be the great hedge against it: in the long term maybe. In the short run, rising rates will drag property prices down and widen credit spreads as defaults rise.

Negative interest rates have made government bonds unattractive to any buyers other than central banks for years now. Investors have searched for yield in alternatives, in illiquid private credit, even in crypto. And they have driven stock markets higher. All of this is underpinned by artificially low rates.

But for how much longer?

“It is hard to position for inflation,” Ewout van Schaick, head of multi-asset at NN Investment Partners, the Dutch asset manager with $355 billion of assets under management, tells Euromoney. “Investors have not had a period this difficult to predict in two decades. And they have not questioned the credibility of central banks in that period.”

They are questioning them now.

Central banks play word games

Financial leaders hoped inflation would prove transitory. Central bankers’ contortions around the word have grown grotesque. At his November press conference, after the Fed announced tapering of monthly bond purchases, chair Jerome Powell complained that many people had misunderstood the word transitory and somehow imagined it implied that high inflation would be short-lived “with a real time component, measured in months, let’s say”.

They should have realised it means that it will be over eventually and not leave behind a permanent change. Powell downplayed the likelihood of the Fed raising rates or shrinking its balance sheet until it sees evidence of full employment. The Federal Open Market Committee altered its wording to say that elevated inflation reflects factors that “are expected to be transitory”, as if the passive mood somehow gets its members off the hook.

One source tells Euromoney: “People are so tired of that word. If they’re still saying ‘transitory’ come the Spring of 2022, central bankers will simply be scoffed at. They may be scoffed at even if they’re not saying it.”

One week after the Fed meeting, on November 10, the October reading for US consumer price inflation showed it rising at 6.2% year on year, the highest level in three decades.

That day, the concern threatened to flow over into stock markets, which sold off sharply, before recovering by the close.

There is still too much liquidity in the system

“Equities have withstood inflation up to current levels without disruption or much concern,” Suneel Hargunani, co-head of equity capital markets Emea, at Citi, told Euromoney that same afternoon, when the chatter on equities trading floors changed. “But when that October CPI print came in, there was slight concern on whether this might be a turning point.

“There is still too much liquidity in the system and a bid for equity and the market shrugged it off again. But investors need to think about how higher inflation and rates impact different sectors and styles.”

He points out that the biggest hit may be to the valuation of the very technology stocks that have led the climb: “Inflation and high rates hurt valuations of growth stocks in particular, and investors might switch into value and into strong brands that can pass on higher pricing.”

Powell, desperate to keep his options open, sounds torn.

“The level of inflation we have right now is not at all consistent with price stability – by the way we’re also not at maximum employment,” he said.

He sought to assure Americans that the Fed will “use our tools as appropriate to get inflation under control”, while admitting it will remain elevated into next year and then should start declining in the second and third quarters.

The central banks think logistics firms should get on top of delivery delays and then base effects should come into play and reduce next year’s headline consumer and producer price inflation numbers.

‘Should’ is the key word.

Powell said: “We have to be aware of the risks, particularly now the risk of persistently higher inflation. We have to be in a position to address that risk should it create a threat of more persistent longer-term inflation.”

If persistent is the new transitory, then a big shift is just getting underway.

Hedging against the inflation shock

On November 11, the day after the US October CPI print shocked markets, Bank of America’s investment strategists threw out a few numbers that capture what they call the inflation shock that follows $32 trillion of global monetary and fiscal stimulus in the preceding 18 months of the pandemic.

As of the end of October 2021, shipping rates were up 153% year on year; food prices up 31%; energy costs up 74%; house prices up 20%. They calculated US CPI running at 7.6% annualized, a 40-year high; China producer price inflation (PPI) running at 14%, a 25-year high and Japanese PPI at 8%, a 40-year high. Next, they say, will be the surge in wages as inflation becomes embedded.

Is it time to panic yet?

There is the actual data and there is what the market is telling us

“You have to look at this in two ways: there is the actual data and there is what the market is telling us,” says Peter van Dooijeweert, managing director in multi-asset solutions at Man Group. “The actual data is saying: climb into a hole and buy canned goods. But markets are saying something different.”

The five-year breakeven in the US is at its highest ever. But van Dooijeweert prefers to look at the five-year/five-year forward breakeven, in other words, what the five-year breakeven looks like in five years’ time.

“That’s at 2.2% now, well below its long-term average,” he says. “Transitory might have been a stupid way to describe inflation, but a better way to think about this is: does the market think this is a permanent long-term problem or not? For now, 2.2% says it does not.”

However, he adds, “if that measure starts to balloon higher, markets will likely react more poorly to the data”.

This is consistent with behaviour in the long end of the bond market, says van Dooijeweert, where investors are looking through live issues such as spiking energy prices and supply chain bottlenecks.

Two-year notes might have moved a lot, with yields having more than doubled, albeit from a very low base, from a nominal 0.16% in June to 0.52% on November 19. That is bad for hedge fund carry trades. But there’s also an opportunity here for active rates managers.

“Our key inflation hedge has been to go short the front end of the US nominal curve where we believe the market will need to price more hikes if inflation remains persistent for longer,” Steve Ryder, senior portfolio manager of Aviva Investors Global Sovereign Bond Fund, tells Euromoney. “As central banks signal removal of emergency accommodation, you see a rolling pattern of flattening down the curves in expectation of a normal hiking cycle. The two-year is usually the last point to move. It will start to when the Fed begins hiking.”

One negative that may not immediately be obvious is that M&A will be more difficult

The fund’s other big hedge is to go long the US dollar.

“It stands out as an opportunity, given broad-based inflationary pressure in the US and potential for more hikes to be priced,” says Kurt Knowlson, senior portfolio manager at the same Aviva Investors fund. "Given further policy divergence, there is still greater scope for US dollar outperformance over the coming months."

Aren’t commodities the big beneficiaries of inflation?

“They could be a hedge,” says van Schaick. “Institutions had sizeable allocations to commodities maybe 15 years ago, but lost their appetite in recent times. Commodities can be very volatile.”

That’s the lesson investors learned in the US shale sector.

“You see high prices, capital floods in, then the price collapses,” he says. “Commodities could be a diversifier for portfolios, especially if there should be a longer period of higher energy prices. There has been a lack of capital investment in energy during the transition to sustainability, which has limited the supply response from investors.”

Michael Kelly, head of multi-asset at PineBridge Investments, is cautious, however: “Commodity price rises are a result of the early bottlenecks that we’re now seeing clear. I would stay away.”

Active managers don’t want central banks to repress rates volatility and remove risk premia from the markets. They’re going to have a field day in 2022, as responses differ across developed and emerging market central banks. But those opportunities come in an expensive asset class that is likely to cheapen.

The central banks of Canada and New Zealand have already moved. At the start of November 2021, the Reserve Bank of Australia abandoned without warning its yield-curve control policy of holding the three-year bond, specifically one maturing in April 2024, at 0.1%. Volatility in the Australian dollar government bond market spilled over into European money markets that have no real connection.

If you are a pension fund, then a move in two-years of a few basis points against you is no big deal. Big moves higher in longer-term bonds would worry investors much more.

Inflation isn’t just the big topic: it’s the only topic right now

Low rates dominate all investment themes. Modest moves up from record low levels may have big effects. After all, a rise from 1% to 2% is a doubling, while a move from 4% to 5% is less dramatic.

“Inflation isn’t just the big topic: it’s the only topic right now,” van Schaick says. “We’re now into Covid winter in Europe, and a fifth wave, with lockdowns that will delay normalization. Yes, there are now fewer ships waiting to unload in Los Angeles. And it’s even possible that a pick-up in inventories could raise a hint of deflation in produced goods. But pressure on costs further upstream will stay with us, no question. And there will be no clarity as to whether inflation is transitory or not until far into 2022, possibly the second half of 2022.”

Before then, he suggests, we’re likely to see a lot more volatility. For now, investors are still putting their faith in developed world central banks that were sounding dovish again in November.

“If the Fed, the ECB and the Bank of England were based in emerging markets, investors might have reacted very differently to the inflation data,” says van Schaick. “But faith in those institutions means they will look through it for now.”

That is particularly evident in stock markets, he says.

“In the current environment, fixed income is far from attractive, so there is no real alternative to equities and still a fear of missing out driving investors from retail to hedge funds to push stocks higher.”

The equities trade still had momentum going into the end of 2021, but van Schaick offers a qualifier: “It is typical late cycle.”

Is this apparent market stability a mirage that will last only while central banks are still buying vast amounts of paper? They have so far only slowed the pace at which they are expanding their balance sheets and not even talked about shrinking them.

What worries van Dooijeweert’s clients is if inflation runs out of control.

“In January and February [2021], the feeling was this could be transitory,” he says. “By May, people were saying: we think it is transitory.

“Now they are saying: we hope it is transitory.”

A question of credibility

“I have been in team transitory,” Jeremy Barnum, chief financial officer of JPMorgan, tells Euromoney. “Though, when you follow the debates between leading economists, team transitory is starting to capitulate and inflation is clearly going to run for a while. We see on the cost side here at the bank that wage inflation for certain skill sets is real. But I do not see this turning into a classic wage-price spiral, with heightened inflation expectations feeding back on themselves.”

How concerned investors should be about rising prices and rising interest rates largely depends on why they are going up.

Jim Esposito, global co-head of the investment banking division at Goldman Sachs, tells Euromoney: “Both with corporate executives and institutional investors there seems to be growing acceptance that inflation is proving more than just transitory in nature. That said, markets are oddly well behaved. If rate markets thought we are going to experience runaway inflation, I doubt we would be staring at a 10-year note yielding 1.58%.”

A world with moderately higher inflation because of higher growth is fine.

“We would have killed for that in 2015 and 2016,” says Barnum.

EM central banks are ahead of the curve. It’s developed world central banks that have their heads in the sand

However, this feels different to many. And the pandemic makes it difficult to draw lessons from previous inflationary episodes.

Paco Ybarra, chief executive of the Institutional Clients Group at Citi, puts himself close to team transitory but not a full member.

“I’m in the camp that believes it takes a lot to change the dynamics of the world," he says. "For years, the conversation has been around deflation. There may be rate hikes and volatility in yield curves, but a lot of the drivers of inflation, such as supply-chain disruptions, may be temporary.

“However, inflation is a phenomenon that is not well understood. And there is not a lot of relevant history to work from. Inflation is almost psychological. It resides in people’s brains. When enough people are convinced that inflation will happen, then it happens. But what lodges that expectation is not clear.”

Of one thing he is certain: “There are reasons to be worried about it.”

What follows in 2022 will be a battle not so much between central banks and inflation as between central banks and inflation expectations.

Spot inflation may be the biggest driver of those expectations, and base effects may come to the rescue of central banks. But winning that battle comes down to their own credibility. That is increasingly in question, even though central banks have dominated markets – almost replaced them – in the years since the financial crisis, and before that the dot-com stock crash in 2000.

“It’s very difficult to accurately forecast inflation in any environment let alone in this unprecedented environment, and this is true for global central banks as well,” says Ryder at Aviva. Their economists don’t know more than anybody else’s economists.

What central banks cannot do is remain firmly dovish at any level of inflation. They’re trying to articulate the risk it becomes persistent to show they are not so far behind the curve and have flexibility to respond if it does. But no one is remotely impressed by a good communicator like Powell playing games with what ‘transitory’ means.

Even investors who feared that the Bank of England might have been making a mistake if it had raised rates in November, shook their heads when governor Andrew Bailey first indicated that it would and then didn’t deliver.

“Other central banks turning their narratives dovish gave the Bank of England cover for that retracement,” says one US source. “But they can’t carry on like this.”

Knowlson says: “There are many global factors driving inflation higher, however the UK is also managing a more structural inflation problem with changes in the labour market meaning the central bank may have to move sooner.”

If the Fed were to panic at the first sign of rising prices, that just takes the economy back to stall speed

Emerging markets, normally hit hard by US rate rises, are another asset class to watch. In Brazil, the official rate rose from 2% to 8% in 2021. In Mexico, rates are also going up. Rates have gone up in Chile. In Poland, they increased twice in the last quarter of 2021 and will most likely continue to increase. The Czech central bank has produced two big rate rises that surprised the markets, hiking by 125 basis points on November 4, it’s largest rise since 1997.

“Emerging market central banks are ahead of the curve on inflation,” Kelly tells Euromoney. “It’s developed world central banks that have their heads in the sand.”

He suggests that before long they will have to pull forward rate rises.

“There will be a moment, maybe in the spring of 2022, when emerging currencies go from lagging to leading, and everyone starts praising the emerging market central banks that got ahead of inflation,” Kelly says. That moment will, he suggests, “be interesting”.

Active managers always second guess central banks, pricing in more or less than they are signalling.

But along with questions over their credibility, central banks face doubts that they can do much about inflation anyway.

“Central banks can choke off excess demand by raising rates, thereby increasing the cost of borrowing and diverting cash into interest payments,” Chris Tuffey, head of IG capital markets Emea at Credit Suisse, tells Euromoney. “But these aren’t necessarily the most effective tools to combat inflation caused by higher input prices for raw materials and labour costs in a tight market.”

Bank of America’s investor survey in early November found two fears dominating that were largely absent from their concerns at the start of 2021. The biggest, cited by 31% of respondents, is a central bank policy mistake triggered by inflation. Those investors are scared of central banks raising rates. The second, cited by 24%, is of inflation itself. This group is scared of central banks not raising rates.

The end of a super-cycle

It is the pandemic’s restrictions on supplies of goods and of labour, together with the boost to demand from the response to it in massive government borrowing and spending and central bank money-printing, that has sprung inflation on the world, after decades with little sign of it in developed markets.

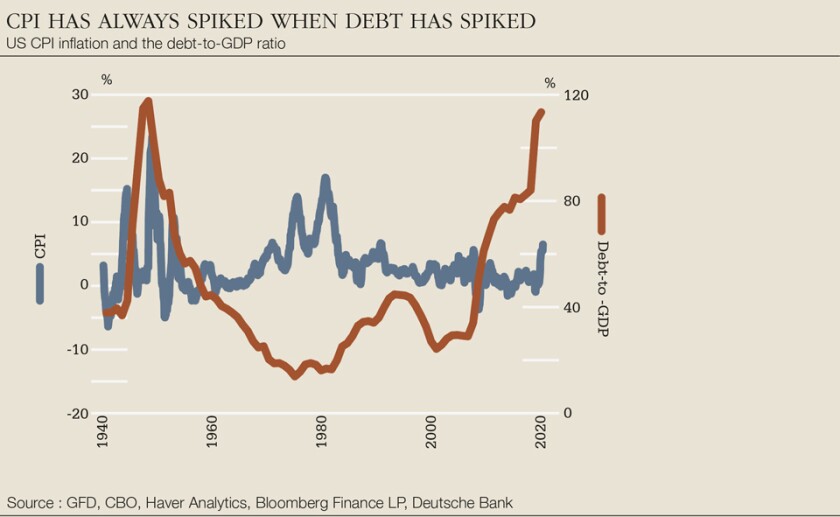

In the years after the great financial crisis, loose central bank policy was the counterpoint to fiscal austerity. But conservative governments have given way to populists. The IMF points out that in the first year of the pandemic, global government, corporate and household debt rose by $27 trillion to $226 trillion.

In a speech in Frankfurt on November 15, Christian Sewing, chief executive of Deutsche Bank, pointed out: “For all the success of the emergency measures against the coronavirus crisis, this debt burden is simply unsustainable in the long term and a constant potential trouble spot for the global financial markets.”

Is this how the decades-long debt supercycle ends: in uncontrolled inflation, aided and abetted by governments that have grown addicted to spending wanting to get out from under their own excesses? That’s the beauty of monetizing government profligacy. When it all goes wrong, politicians can blame the central banks.

In Germany, inflation hit 4.5% for October and 5.2% in November. The ECB is even more reluctant to raise rates than other leading developed world central banks. In October, Jens Weidmann, hawkish president of the Bundesbank and the longest-serving member of the ECB’s governing council, stepped down years ahead of his term ending.

Weidmann referred in a statement to the Bundesbank having contributed with its analytical competence as well as its core convictions to the recently concluded review of ECB monetary policy.

"A symmetrical, clearer inflation target has been agreed. Side effects and in particular financial stability risks are to be given greater attention,” Weidmann said, before getting to the point. “A targeted overshooting of the inflation rate was rejected."

Inflation will be more persistent than central banks have assumed

Looking ahead, he pointed out that all now depends on how this strategy is "lived" through concrete monetary policy decisions.

"In this context, it will be crucial," says Weidmann, "not to look one-sidedly at deflationary risks, but not to lose sight of prospective inflationary dangers either."

The head of Germany’s largest bank has grown sceptical on monetary stability. Sewing hears in conversations with Deutsche clients that they are all preparing for inflation to stay higher for longer.

He states: “I think that monetary policy must counteract this – and sooner rather than later. The supposed cure-all of the past years – low interest rates with seemingly stable prices – has lost its effect, now we are struggling with the side effects.

“In short: the consequences of this ultra-loose monetary policy will become increasingly difficult to fix the longer central banks fail to take countermeasures.”

Euromoney asks James von Moltke, chief financial officer of Deutsche, how this will play out. He says: “My personal view is that inflation will be more persistent than central banks have assumed, and markets are trying to understand how this likely translates into the rates world and what higher rates mean for households, corporations and sovereigns.”

If central banks are already behind the curve on inflation, will they have to raise rates sharply and keep them high to contain it?

“It is the question of the decade,” says von Moltke. “Inflation will likely come off the recent levels of 5% to 6%. If it settles around 2%, then great.”

If that happens, central banks will call themselves heroes, even if no one else does.

“But in my view, there is a risk in continuing with quantative easing given such loose financial conditions,” von Moltke adds. “If inflation settles at 3% to 3.5%, we are in a different world.”

Of course, banks are not disinterested spectators in all this. They want rates to go up.

Von Moltke says: “We felt the downside from negative rates in the private bank and the corporate bank and stand to see the upside if rates rise and, ideally, the rate curve steepens.”

From a stylized 100bp parallel shift in the rates curve, Deutsche would gain €700 million of revenue in the first year and €1.2 billion in the second, mostly in the retail bank.

“That’s a big benefit,” von Moltke says, “which mostly falls to the bottom line.”

One of the few good places to put money if rates do rise sharply might be bank stocks, though even that depends on how soon and how far default rates climb.

The virus and inflation

Most bankers Euromoney speaks to argue that Covid ceased to be a prominent economic factor at the start of 2021. Let’s see what they say if new variants, such as Omicron now spreading in southern Africa and beyond, lead to further lockdowns and even worse labour shortages, as fear of catching it and the need to look after sick family members further restricts participation in the labour force.

The inflation furore is all about Covid. Big shifts in base effects make the macro data, including alarming-looking inflation numbers, hard to interpret.

The world is awash with liquidity [but] the velocity of that money has fallen off a cliff

Did the virus arrive at what was already a tipping point between the old era of low inflation and a new one? The magic of QE has long since worn off.

Esposito says: “If you look at the amount of money in the global system, the world is awash with liquidity. What is less well understood is that the velocity of that money – how quickly and how often it changes hands – has really fallen off a cliff since the global financial crisis.”

Why is that?

“It might be because of growing wealth concentration partly driven by all the fiscal and monetary stimulus you have seen around the world — the wealthy do not spend in the way that others would," Esposito says. "It might also be because of increases in productivity driven by technology.”

Technology has been a driver of productivity chiefly at technology companies, but also of deflation, though it is not the only one.

Ybarra says: “There is a long-term story that the deflationary impulse of the last 30 years was driven by the growth of the global manufacturing workforce, led by China but right across emerging markets. That may be close to played out as China moves up to a consumer society. And companies are rethinking supply chains, moving production closer to home where labour markets may be more stretched.”

He says: “Higher labour costs are what bring inflation back.”

Ybarra admits that inflation need not be a bad thing. It’s the speed at which it picks up and the level it gets to that then raises the question of whether central banks have the tools to deal with it.

“For monetary policy to be effective against inflation, it needs to be on time,” he says. “That’s going to be a tall order for central banks in a world that needs growth as it comes out of the pandemic.”

Barnum agrees but takes a different angle: “Yes, people may find it odd that with a CPI print of 6.2%, the Fed continues to buy bonds with rates at the zero bound. But if the Fed were to panic at the first sign of rising prices, that just takes the economy back to stall speed.”

Euromoney presses: Aren’t the chances clearly rising that, having held off on raising rates, the Fed may find itself having to hike them more rapidly and much higher?

“Two months ago, I would have said the chances were very low. Today, it may be higher, but it would still be relatively low,” Barnum says. “I still find it a remote possibility.”

Tearing up capital markets calendars

Bankers don’t know what will happen to their own businesses if inflation outstays its welcome and high long-term inflation becomes endemic.

Euromoney asks Sharon Yeshaya, chief financial officer of Morgan Stanley, what impact persistently higher than expected inflation might have on debt and equity underwriting businesses that bring in billions of dollars a year of revenue for the firm.

Inflation is a very bad thing for fixed income owners

The conversation has raced across the potential benefits to secondary trading businesses. Yeshaya tells Euromoney: “One positive may be that volatility in markets will lead to higher volumes of customer activity at wider bid-offer spreads, though the impact on inventory may be a downside. Another is that high rates generally benefit financial firms.”

But now comes a pause.

“I am not sure what will happen with underwriting calendars,” Yeshaya says

Here’s one theory. Inflation and rising rates could tear them up.

The disruption will be particularly intense in fixed income and debt capital markets, where even for weaker credits high inflation turns positive nominal coupons into negative real ones and makes them a charge to investors for the privilege of lending to risky borrowers. Spreads compress as rates fall. They may be insulated from moderately higher inflation driven by strong growth through normalization. But they widen when rates rise fast.

Even worse, inflation severely erodes the value of principal when it is eventually paid back after five or 10 years, even by high-quality issuers such as governments.

“Away from Tips [Treasury Inflation Protected Securities], linkers and other inflation-linked debt, which is immunized against it, inflation is a very bad thing for fixed income owners,” says Tuffey. “Invest $1 million in a 10-year bond, and if inflation runs higher than expected, when you get your money back it’s not worth what it was in real terms when you invested.”

For retail buyers, the sum you invested in government bonds that would have bought you a car, might get you a bike when it is repaid. So why invest in financial assets? Why not invest in real ones, even if they do depreciate? Just buy the car before prices shoot up.

It is the asymmetry in different countries’ emergence from the first two years of the pandemic that has unshackled inflation, for some a fearful memory from the 1970s but an episode from economic history books for most working in financial markets today.

High demand for goods and services in economies that have reopened strongly – notably the US – has met supply bottlenecks in producing countries, particularly in Asia, still disrupted by lockdowns.

Our corporate clients are looking to change their supply chains

Goods that were once immediately available on demand, no longer are. The obvious example is the shortage of semiconductor chips used in auto manufacturing that has closed factories and led to rising prices for second-hand cars. Freight costs have shot up. There’s even a shortage of containers. Team transitory still expects this to pass in the middle of 2022 and soaring energy costs also to decline, especially if Opec boosts oil production.

But rising prices are spreading to more and more items in inflation baskets, notably shelter.

Companies did not appreciate until the pandemic that the complex yet highly efficient supply chains they had built during 30 years of globalization were also extremely vulnerable.

Now they see it but are struggling to cope. Companies will need to build higher buffers of key inputs, such as raw materials, components and maybe money too.

“Our corporate clients are looking to change their supply chains,” says Henrik Johnsson, global co-head of capital markets at Deutsche Bank, “and that creates a massive need for working capital across their subsidiaries in various countries.”

As 2021 drew to a close, equity investors seemed bullish after strong third-quarter earnings, with markets close to all-time highs. But nerves are jangling.

For monetary policy to be effective against inflation, it needs to be on-time. That’s going to be a tall order

“It seems to me that the equity markets need a breather,” says Hargunani. “But in recent years investors have learned not to fight the central banks which drive all financial markets.”

M&A enjoyed a record year in 2021, driven up by rising stock markets and driving them higher still in turn, in a classic positive feedback loop.

Investment bankers hope that this will continue if inflation rises because companies that don’t have the pricing power to pass on higher input costs to customers will seek the scale and dominant market position to do so. Competition authorities may have their own take on that.

However, Yeshaya at Morgan Stanley, a top M&A advisory firm, harbours doubts about the oft-repeated line that the prospect of higher inflation will drive continued strategic corporate deal-making.

“One negative that may not immediately be obvious is that M&A will be more difficult,” Yeshaya says. “Boards and executives need to be confident that they can execute their business plans and defend their budgets before they launch transactions. If they are not confident, they may be less keen to integrate the external uncertainties of M&A.”

Winners and losers

Everyone in the capital markets will be watching fund flows like a hawk in 2022. Might money flow out of fixed income and into equity? And if so, into what sectors and stocks?

Banks have convinced investors that they are the defensive sector that will be a big beneficiary of rising rates. That ignores the risk of rising rates driving defaults. And what will happen to bank deposits – in bounteous supply and an unwelcome burden in the era of negative rates – if it becomes even more obvious that high inflation is taxing them punitively.

Borrowers will have to prepare for greater volatility in supply of money

Watch for outflows of bank deposits as a big signal of potential market distress.

Retail investors, including furloughed workers stuck at home, poured money into equities in 2020 and 2021 driving the meme stock craze. Does that continue as stock picking for companies with genuine pricing power that can cope amid inflation gets harder?

Above all, what can fixed income investors do? The inflation-linked markets are comparatively small. The structured-note market, that used to include inflation features, has shrunk as that arbitrage disappeared in the era of QE – and bankers see no sign of a revival yet.

Swapping bond portfolio holdings line-by-line from fixed to floating is expensive and bothersome and adds both liquidity and counterparty risks. Fixed income holders could put on macro hedges against rising rates, but it gets hard to price volatile markets and it needs counterparties to take the other side of the trade.

The big action will remain in curve flatteners or steepeners, with investors taking views on whether short- and long-term rates have moved too far out of step. These trades are cheap to implement. But they’re a relative value play. They don’t offer much protection against a sharp rise in all rates.

We are in a period where investors are pausing and waiting for a clear direction

What happens to the credit markets if risk-free rates climb and real rates turn positive? The unwind of the decades-long low-rate trade could drain the money that has flooded into credit in search of yield.

“If I could earn 5% a year from government bonds, I wouldn’t even bother with credit,” says one banker who earns his living from the credit markets.

Owners of so-called risk-free bonds will suffer the biggest pain as rates rise. But after that, government debt could even look attractive for the first time in many years.

Investors were focusing on the string of central bank meetings in the third week of December 2021 and wondering whether or not the widely expected volatility of 2022 might start early. Markets remain utterly in thrall to the central banks, even while starting to doubt them.

“So many people in the markets have never seen inflation and don’t know how it will work out,” says Jeff Tannenbaum, head of Emea capital markets at Bank of America. “They are doing nothing until they see the central banks move. We are in a period where investors are pausing and waiting for a clear direction.”

For now, we are in limbo. Whatever else 2022 brings, that won’t last.

How do you position for the inflation pivot?

All across the buyside and the sellside you hear the same concern: very few people working in developed world financial markets today have experienced high inflation. Even team persistent don’t know what to do about it. They’re stuck, waiting to see if it will run them over.

Michael Kelly, global head of multi-asset at PineBridge Investments, a private global asset manager with $140 billion under management focused on high-conviction investing, does recall inflation. And he’s not waiting around to be hit.

Kelly got his first start in finance in 1980 at Townsend Greenspan, home to Alan Greenspan before he moved on to chair the Federal Reserve. Inflation hit 13.5% in 1980 and, as president Ronald Reagan took office, Fed chair Paul Volcker raised the Federal funds rate to 20% in an effort to combat the price rises that had prevailed since the mid 1970s. In 1982 inflation came down to 6.2%, then 3.2% in 1983.

Kelly recalls a debate in 1980 between two famous economists: Henry Kaufman arguing for persistent high rates to contain inflation and Greenspan contending that the US was entering a new era.

“I was an impressionable young kid, but I saw a big pivot after 1980,” Kelly tells Euromoney. “And what we are living through right now is another big pivot.”

Kelly is in team persistent but concedes that investors should be careful not to get too far ahead of the change about to unfold.

“It’s easier to figure out where not to lose money than it is where to make money,” Kelly says.

But he has a few ideas. First, one that has already played out.

“At the start of 2021, we were buying short-dated Tips [Treasury Inflation Protected Securities] in the high twos and exited those in the low fours. That was clear cut. Right now, nothing is clear cut. So, you have to be creative.”

One place to turn is floating-rate instruments. PineBridge sees value in collateralized loan obligations.

Kelly says: “The equity and subordinate tranches offer a lot of protection to AA-rated CLOs, where you can get from 160 basis points to 180bp and which, being floating rate, we think will benefit when policy rates move up.”

Go long EM debt

But perhaps his most intriguing suggestion is to prepare to go long emerging-markets debt. That is traditionally not a good place to be when US rates rise.

However, Kelly suggests: “Investors need to be looking at emerging markets now and sharpening their pencils. Local-currency emerging-market debt will be a double-digit mover in 2022.”

One seemingly counterintuitive move is to go long China.

“Too much of the country’s mass of savings has gone into property, which has driven inequality," says Kelly. "But the Chinese government is now moving to ensure bank liquidity for those developers that did not cross its three red lines. There will be survivors among those, notably the state-owned enterprise (SOE) property developers, now offering notably wide money-good spreads.”

But winning property developers are just a taster for the main event.

“I would be looking to position in the world’s second-largest government bond market, which is so heavily owned by China’s own banks and insurance companies,” says Kelly. “That may be the only government bond market in the world where rates will be lower a year from now than they are today. And I don’t think the renminbi will be allowed to fall pari-passu.”

US financials

In equities, all investors are looking for companies with pricing power. Kelly makes a more conventional call: US financials.

“Having come through a decade when there wasn’t much demand for credit, most of these companies are in very good shape and paying out 100% of earnings. When the credit pulse comes back, they can really grow.”

He sees big asset owners increasingly allocating to multi-strategy hedge funds promising low volatility, of around 4%, but also low beta with limited correlation to the main market indices.

He suggests: “A fund that goes short BBB CLOs and long the double As, levered just two or three times, might generate mid-single digits with zero outright market exposure and maybe 4% volatility.”

But pension funds won’t be allocating to such strategies in large size because they raise their overall expense ratios and eat up their liquidity budgets.

This is all going to get very tricky for fixed income investors. The argument between team transitory and team persistent may be much shorter than their struggles to cope with inflation.

Kelly says: “Over 20 years, the global savings rate has gone high and stayed high. And on top of that savings glut, we have also had massive central bank balance sheet expansion in excess of GDP growth by many multiples.

“Central banks realise that they have pushed markets too far up and that they need to find a path back home. It’s not going to be easy and it’s not going to be quick, because it’s taken 20 years to get here. But eventually you hit a tipping point.

“And Covid was the tipping point.”

…

Capital markets: The end of easy money is now in sight

Capital markets may be about to endure their own version of supply-chain disruption. Armin Peter, global head of debt syndicate and head of sustainable banking Emea at UBS, tells Euromoney: “Over the last two decades, since the dot com crash and then the great financial crisis, even though there have been bouts of volatility, the markets have moved in one direction, towards an ever-declining cost of capital, lower rates, and cheap funding always available on demand.”

Ever cheaper debt fuelled growth.

“Having money almost didn’t mean anything,” says Peter. “Companies didn’t work with financial buffers. It was all about balance-sheet efficiency. If you needed more funding, you just went and got it.”

That may not be so easy in future. Business models that have been built along just-in-time supply chains using extremely cheap funding will be in trouble. The defaults banks reserved for in the first half of 2020 didn’t appear and lenders have written back reserves through their profit and loss accounts.

But defaults may only have been delayed. It’s been a long time since high interest charges on their debts were a worry for borrowers and a possible cause of default. And it won’t become an issue if the underlying 10-year reference rate rises from 1.6% to 2.6% and credit spreads remain around 100 basis points or widen slightly.

But volatile rates can drive volatility in credit spreads and for that matter in equities. What happens if underlying rates go to 4% and spreads to 200bp?

Paco Ybarra, chief executive of the Institutional Clients Group at Citi, says: “When you think about the potential impact of rising rates, think about a reversal of what has happened because of lower rates and the desperate search for yield. Private equity may see less of the yield seeking money and business models that are highly leveraged may suffer.”

He adds: “Sovereigns have issued vast amounts of debt at zero spreads, and there may be questions over the sustainability of that.”

Price value of a basis point

In 2022, we are all going to be hearing much more about the price value of a basis point: that is how much the price of so-called risk-free government bonds might fall for each one basis point rise in rates. A 1bp rise might cut 12.5bp off the value of a 30-year Treasury bond, but just 4bp off a five-year. So that 100bp parallel shift in the yield curve could inflict serious damage on holders – including bank treasuries – of longer-dated government debt that is supposed to be easily converted into cash at par. Therefore, investors will look to shorten duration.

The real yield on 30-year US Treasuries is now roughly negative 50bp. Inflation is now running at 40-year highs. Look back to the early 1980s and the real yield on 30-year Treasury bonds was around 9% in 1983. A 700bp rise in 30-year yields, from a nominal 1.975% in late November 2021, would bring carnage. Nobody can even think of it.

Investors want higher rates on the bonds that they buy in future of course. The problem is what happens to the vast quantities of bonds they already own as we get there.

Issuers want to extend duration right now and lock in low rates while they can. Investors want to do the opposite. This hasn’t hit the new-issue markets yet because of technical factors: the central bank bid and perhaps the biggest single contributor to bond investor performance in 2021 which was the new-issue premiums available especially on corporate debt.

Come January 1, 2022, and bond investors start from scratch once more staring into a wall of worry.

“Borrowers will have to prepare for greater volatility in supply of money,” says Peter. “Funding and capital will likely have a higher price. For borrowers that have reengineered their business models and decided how much they need to raise, even if that can be done, it may not be available immediately. It might take three weeks. It could take three months.”

Do deals now

The classic advice from capital markets bankers to issuers ahead of any period of expected volatility is always to do their deals now, while they still can. For now, technical factors, dominated by continued central bank buying of bonds, are keeping rates low, even while the expectation grows that they will soon pop up and may even shoot up.

Jeff Tannenbaum, head of Emea capital markets at Bank of America, confirms that borrowers are seeking to take advantage of benign conditions while they still last.

He says: “Issuance has been down in 2021 compared to 2020, but in the fourth quarter a lot of borrowers that had not been planning to issue began pre-funding 2022 because they think inflation will drive coupons higher.”

And this is not just a feature of the debt markets.

“In equity markets there has been a high level of public capital raising such as through IPOs,” he adds. "If an owner is looking to monetize a business, current high valuations, discounted against record low rates, make it attractive to do so now."

That is especially so for any company founder or private equity owner looking to sell a business that might be sensitive to inflation and not able to pass on higher input costs to customers.