It was all going so well. European banks entered 2022 in their best shape for years, having de-risked their business models and set themselves up to take advantage of the end of negative rates.

According to analysts at Bank of America, next year European banks could even meet their cost of equity, assumed at 10%, for the first time since the global financial crisis. A share buyback boom had underlined new hope that 15 years of regulatory tightening could soon be over, while optimists even thought that if rates weren’t zero or negative, banks’ core deposit gathering businesses could spring back to life.

Jump to:

Then came February 24 and Russian president Vladimir Putin’s long mooted but scarcely believable full-scale attack on Ukraine. European bank stocks fell 8% on the day it happened, much more than the wider Stoxx index, and have continued to fall.

Key European lenders such as Societe Generale, Raiffeisen and UniCredit have extensive operations in Russia. And the wider industry faces the prospect of the crisis pushing energy prices and therefore inflation to such a level that the resultant higher rates could end up hurting them even more than years of negative rates have done.

RELATED:

So, has the European bank recovery been extinguished before it has even really started?

To answer this question we must cast our minds back to September 2020, six months into the pandemic, which might have been the all-time nadir in European banking. On September 25 that year, the Stoxx Europe 600 Banks index slumped to its lowest level since 1987, even after the wider market had recouped most of its early Covid losses. With the promise of positive eurozone interest rates as distant as ever, the sector was trading at about half its tangible book value, with a 56% discount in the eurozone, according to Berenberg.

Things became even gloomier when the Bank of England started to consider negative rates as the end of the Brexit transition period loomed, despite the damage that policy had done to continental European banks over the previous five years.

Following the financial sanctions imposed on Russia in the aftermath of its attack on Ukraine, is the sector headed back to that point? Sharply higher rates, driven by inflation, look inevitable. Growth will likely slow as energy prices rise all the good work of the last few years will be undone?

Momentum

It is important to remember that the recovery of Covid-related losses in European bank shares in 2021 wasn’t only, or even mainly, about interest rates.

Government support measures saw banks come through the pandemic with minimal loan losses, including those in southern Europe, despite a rapid buildup of reserves in 2020. Largely as a consequence, banks’ results consistently beat market expectations last year, even when policy rates remained unchanged.

European banks began 2022 with an earnings momentum that had never looked so good, according to Citi analysts, based on the number of earnings upgrades over downgrades.

As long as banks trade below book, they’re very much incentivized to buy their own stock, and as long as they’re buying their own stock, they’re not going to do M&A

Meanwhile, bank capital ratios have risen to a record high, after a decade of regulatory tightening and as the feared Covid losses didn’t materialize. That has allowed the Bank of England and European Central Bank (ECB) to green light a price-boosting share buyback boom only a few months after they lifted the blanket ban on dividend distributions imposed early in the pandemic.

Interest rate expectations – which have been creeping up for over a year and accelerated in early 2022 – could bring about an even bigger turn. Far from implementing negative rates, the BofE raised rates for the second time in a row in early February, with further hikes expected. That ended up reinforcing bullish views on UK bank stocks.

And a more hawkish mood at the ECB could signal a potentially even greater shift, as there has long been more doubt about rate hikes in the eurozone than in the US and the UK.

Comments from ECB governor Christine Lagarde at its February 5 policy meeting sent macroeconomic analysts and then bank equity analysts rushing back to their desks to tweak their models upwards.

Rather than two hikes before the end of 2023, according to KBW, interest rate markets were suddenly factoring in four. The policy rate was now set to rise from -0.5% to 1% by end of next year, according to UBS.

“This a game changer in the industry, especially in Europe, where rates are negative,” Banco Santander chief executive José Antonio Álvarez says, discussing the impact of rates on banks in a recent interview with Euromoney that took place before the imposition of financial sanctions on Russia, as did several interviews included in this story.

Of course, higher expenses are a rising worry for struggling households and businesses, especially given the Ukraine situation. Adding higher borrowing costs is the last thing they need.

Many central bankers and influential economists disagree with the idea that negative rates – rather than low economic growth and deflationary risks – harm banks. However, even academics agree that an end to rates at or below zero because of higher inflation would help the banking industry.

“Moving away from the zero lower bound does help the banks,” says Thorsten Beck, professor of financial stability at the European University Institute. “Margins have been squeezed because they can’t reduce deposit rates much further, while lending rates have been depressed.”

Expectations

European bank shares closely follow inflation expectations, albeit with a lag, research from Deutsche Bank shows. And even a 50-basis point hike in policy rates leads to about a 10% increase in European banks’ bottom line, according to analysts at KBW and UBS.

Italian banks, domestically focused Spanish banks and German banks could be among the biggest beneficiaries, partly because of a greater prevalence of floating-rate loans in southern Europe.

Shares of CaixaBank and Commerzbank were both up about 15% in the first half of February, compared with a 2.5% sector-wide rise.

Higher Federal Reserve rate expectations have also bolstered bank share prices in the US. But interest margins have fallen more in Europe, especially in continental Europe, because neither the Fed nor the BofE have pushed their rates below zero.

That’s why, after years of underperformance, European bank shares have recently seen more of a boost than the US banks from rising inflation and interest-rate expectations.

Bankers at firms based in the eurozone, Switzerland and Scandinavia all say they have found negative policy rates exceptionally difficult to manage because it is so hard to pass them on to depositors.

Persistently negative rates, they say, end up undermining their core maturity transformation business as branch-based deposit gatherers.

After 15 years of pain, could this new rise in inflation – combined with the better outlook on capital – bring about a new supercycle in banking in Europe?

Even before Russia invaded Ukraine, investors and most bankers weren’t quite ready to promote that idea yet. Despite the ECB’s apparently more hawkish tone – and before Putin’s move – banks were still trading at a 15% discount to tangible book value in Europe, with a 20% discount in the eurozone, according to Berenberg.

There was the worst alignment of stars you could have seen in the banking sector in the past three or four years

The market may be right to be cautious. Most recently, in 2017, interest-rate expectations sent European banks out of the emergency ward only to send them right back in shortly afterwards.

But perhaps after a decade or more of low inflation and even deflation – resulting in razor-thin interest margins – it is time to take stock of how different the sector will be in the coming decade.

The fiscal response to Covid, coupled with the backlash against globalization in mainstream politics and most recently the war in Ukraine, may have made inflation structurally higher. Central bank reluctance to act could merely exacerbate this, forcing them to act more aggressively later.

One bank specialist at a top-tier US asset manager describes the case for a structural bull market in banks like this: banks caused the last crisis, so they remained stuck in a post-2008 market trough for a decade and a half. They had to increase their capital buffers by about three times, deleverage, ramp up compliance spending and rein in activities such as prop trading and parts of consumer finance. Now that’s done and there’s the prospect of a normalization of interest rates.

“You can argue that most of the stars are aligned,” he says.

Jean Pierre Mustier, who stood down as chief executive of UniCredit last year, has a different perspective.

“There was the worst alignment of stars you could have seen in the banking sector in the past three or four years,” he says. “There was low growth, negative rates and then the Covid crisis, which created additional provisions but also a slowdown of the economy. Banks could not have been in a more difficult situation in 2020.

"Today, there’s a normalization of bank profitability, with the Covid crisis behind us. There have been writebacks of provisions and a normalization of the payout policy, with a windfall of accumulated dividends. And there’s been an accumulation of capital beyond the provision write-backs due to regulatory changes which created extra capital buffers.”

European banks, in other words, may no longer be heading towards disaster because of rates – but that doesn’t mean they’re in a good place.

Targets

Bank stocks have burned investors so badly that it is still hard to believe that most European banks could ever meet their cost of equity, never mind comfortably surpass it.

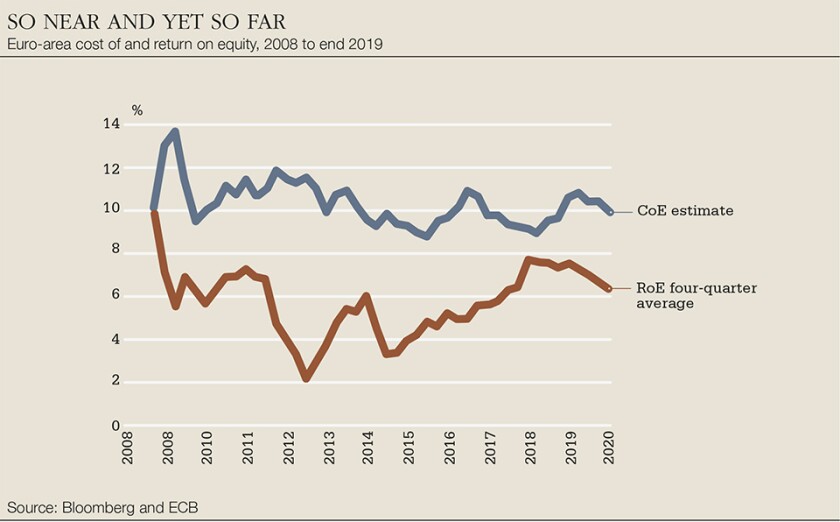

Over the past decade, there has often been a sense that some banks in Europe targeted a 10% return on equity or close to it not because they had much chance of achieving that, but because 10% is the generally accepted cost of equity – how much banks need to reward investors, at a minimum, for the risk versus 10-year government bonds.

Targeting a much lower return on equity is tantamount to saying there was no long-term case for owning the bank.

The 2020 resignations of Commerzbank chairman Stefan Schmittmann and chief executive Martin Zielke highlighted the danger to bank leaders of this perception. Concern about profitability only grew after Zielke reduced the medium-term return-on-equity target to just 4%.

More ambitious targets, on the other hand, have ended up damaging market credibility.

Today, bankers are more optimistic than before about achieving their cost of equity based on the expectation of a more propitious environment in regulation and rates, as well as cost cuts.

Sell-side analyst consensus in February, for example, suggested Commerzbank would reach chief executive Manfred Knof’s 7% target for return on tangible equity by 2024.

The eurozone’s largest bank, BNP Paribas, was among the banks targeting a 10% return on tangible equity in its last three-year plan in 2017.

BNPP eventually achieved that level a year late, partly thanks to the post-Covid capital markets boom. In February, it unveiled a 2025 target of 12%, even though it was still trading at a 27% discount to tangible book, according to Berenberg.

For much of the past decade bankers have clearly been too optimistic about rising interest rates. Could the opposite be the case now?

Divergent growth

Nuno Ferreira, a consultant at McKinsey, says that a new era is dawning across Europe’s banking sector. The next 10 years will be about “divergent growth”, with different firms making different choices for the future.

This follows the “convergent resilience” of the previous 10 years, when banks focused more on meeting new regulatory demands, building capital and efficiency.

“The question now is what a bank can do to grow the top line,” says Ferreira.

“That doesn’t just mean financial intermediation and increasing the balance sheet,” he says, pointing to the scope to add services such as utility bills and property searches to the traditional mortgage product.

With listed fintech stocks starkly underperforming incumbent banks over the last six months, buying fintech companies is indeed one increasingly feasible choice for banks. BBVA and BNP Paribas are both newly flush with capital after selling retail banks in the US for more than $10 billion each. Now BBVA is ramping up M&A in fintech. In February, it led a £75 million capital raising for UK digital lender Atom Bank, of which it owns 39%. The same week, it announced a $300 million investment in Brazilian neobank Neon, bringing its stake to 29.7%.

BNPP has similarly flagged technology and innovation, and the potential for bolt-on acquisitions linked to its business model, for the proceeds of its US sale.

“We aim to really pivot from an environment of constraints into growth – driven by technology and sustainability,” BNPP chief financial officer Lars Machenil tells Euromoney, describing the new strategy.

Chris Flowers, chief executive of financials private equity firm JC Flowers, has long argued that the natural reaction to negative rates, especially for mid-tier and private equity-owned banks, is to shrink, return capital or merge – the latter being another means of reducing capacity.

Hamburg Commercial Bank, which Flowers jointly controls with private equity peer Cerberus, shrunk its balance sheet by a third in 2020.

Serious disincentive

Recently, that theory has started to apply to larger lenders too as the vogue for share buybacks has spread. Tough capital requirements, on top of ultra-low rates in developed Europe, are a serious disincentive for banks to lend, UniCredit chief executive Andrea Orcel told Euromoney in mid-January.

His plan consequently envisages a reduction in risk-weighted assets from €340 billion to €325 billion by 2024. The plan also includes a commitment to return €16 billion to shareholders over the next year, mostly by buying back shares.

Flowers isn’t convinced this dynamic will change much.

“Higher interest rates, should they occur, will improve the profitability of European banks,” he says. “Maybe it will improve their share prices – and you would think that would result in banks being willing to grow their balance sheets or at least shrink less.” The difficulty, according to Flowers, is M&A.

“The need for consolidation and the impediments to consolidation have not changed,” he says.

Others agree. Mergers among larger mid-tier banks in Europe have slowed since a surge in 2020. Branch and workforce cuts are more difficult in Europe than in the US. Such reductions, however, are even more important in mergers, as branches have become less important. Integrating back-office systems is increasingly complex and risky too.

Banking union in the EU remains incomplete. The French presidency of the Council of the European Union is unlikely to prioritize the European Deposit Insurance Scheme project, which seems to have stalled, according to research from Mediobanca.

Because of similar headaches, would-be deals have either collapsed or never got off the ground – including recently mooted mergers between BBVA and Banco Sabadell, UniCredit and Banca Monte dei Paschi di Siena, Virgin Money and TSB, and between Commerzbank and Deutsche Bank.

Despite rising inflation, BNPP’s new plan doesn’t factor in rising margins due to an end to negative rates.

Similarly, UniCredit chief executive Andrea Orcel’s new strategic plan announced in early December 2021 targets a 10% return on tangible equity, up from the 8% Mustier targeted in 2019. But Orcel’s plan also assumes rates will remain negative, which is a long way from the level implied in the forward rates market, even if analysts think other elements of the plan are more optimistic

According to analysts at BofA, next year European banks will meet their cost of equity for the first time since the global financial crisis.

“The market got used to a different world in banking after 2008,” says BofA European banks analyst Alastair Ryan. “It takes a period for the market to reassess the industry. We’re still in the middle of that; plus inflation is going up in a way we haven’t seen for decades.”

Since 2008, regulators have forced banks to set aside capital, deleverage and de-risk their loan and treasury portfolios. Now they’re less pressured on the capital front and better positioned to meet higher demand for loans in areas such as mortgages, according to Ryan.

The benefits of rising rates could be even greater if banks saw steeper yield curves as an opportunity to take longer-term exposures in their treasury books.

This return to a more profitable deposit business due to higher rates would come at a time when banks are exceptionally rich in deposits.

“It is almost an ideal setup for banks’ profitability to rise,” Ryan concludes.

One caveat to this bullish view is the danger that rising rates and the tougher-than-expected international sanctions response to Russia’s attack on Ukraine will eventually trigger a recession, cut loan demand and hike defaults.

For the last six months, however, the rise in inflation expectations has merely triggered a market rotation away from growth to value stocks.

Banks and energy companies outperformed technology companies by 35% between September and late February. According to research by JPMorgan, as the Ukraine invasion became more likely, that movement to value stocks – and towards European rather than US equities – had further to go, assuming bond yields continued to move higher, as geopolitical concerns would blow over after a few weeks.

Growth stocks were still trading at multi-year highs, the analysts reasoned. That position looks pretty optimistic now.

European banks entered 2022 in their best shape in decades, according to Sam Theodore, a former ratings analyst now working as a consultant to the Scope Group. He notes that banks have spent years de-risking business models and balance sheets and have come out of the Covid crisis with their reputations far less bruised than after 2008.

However, even if fears about Russia eventually dissipate, it is hard to see European banks getting back to the valuations of two times book or more that they enjoyed for most of the 2000s. European banks will only earn a return on tangible equity of around 8.4% next year, according to Berenberg.

Even the relatively bullish researchers at BofA expect only a small majority of European banks next year will meet their cost of equity, assumed at 10%. That means that most banks in the eurozone will still earn below that cost of equity.

This is partly to do with capital, which increases the return-on-equity denominator. The Covid crash didn’t tip over the banks, but it proved why they need to be so well capitalized.

The other factor is competition, which nowadays includes financial technology companies, as well as the mutual and public-sector banks that remain dominant in retail banking across much of Europe.

“We’ll have plenty of competitors in the deposit market: old banks, plus others, using digital channels,” says Santander’s Álvarez. “Those channels will be much cheaper, and competition can increase there. Are we going to have the same deposit elasticity to interest rates as before? Probably not. That elasticity will be higher.”

Despite fintech’s largely unproven profitability in Europe, investors have fallen over themselves to fund neobanks in the last decade.

“Fintech is more competitive against banks than before because it’s been fuelled by a tidal wave of capital,” says Diego de Giorgi, BofA’s former global head of investment banking.

He’s now working alongside Mustier at Pegasus Europe, a financial services-focused special purpose acquisition vehicle.

For his part, Mustier adds that the unlikelihood of European banks trading at two times book – or even close to it, like US banks – is also to do with the likelihood that economic growth will remain low in Europe.

“Even if rates would normalize, which would have a positive effect on net interest income,” says Mustier, "European banks’ profitability will remain around 10%, with a cost of capital which might be around 10%, so they could at best aspire to get to book value, with a few exceptions."

On the other hand, as he acknowledges, European banks will be doing a lot better than before even if they trade near or above book value. After all, in the two years before Covid, eurozone bank stocks were typically trading at about a 30% discount to book, reflecting a return on equity of around 6% or 7%, according to the ECB.

If more European banks are meeting their cost of equity, are more capital-rich and trading above book value, could that then open more strategic options such as M&A?

Even before Covid there was a sense of a turn away from the post-2008 decade of reducing risk and shoring up balance sheets. Mustier’s exit from UniCredit in some ways encapsulated that trend.

On his first results call last spring Orcel proclaimed he would “move UniCredit decisively away from a phase of significant restructuring and retrenchment.”

Orcel made no attempt to emulate Mustier’s aversion to M&A in a recent interview with Euromoney.

Problems

That is good, as consolidation – or lack of it – is still one of Europe’s biggest problems.

“The fundamental problem is the lack of growth and competition from too many banks,” says a financial institutions banker. “The pricing power of banks isn’t that high. That will hold back the rally. Banks will probably still trade slightly below book value.”

Bank leaders, however, tend to argue that their stock is trading below book not because of a lack of M&A but because they are undervalued. Their position, after all, is predicated on being able to argue that their firm is on its way to meeting its cost of equity if it isn’t already there.

Policy choices affect how good the recovery will be, which in turn affects how many firms will be over-levered or need restructuring

This could lead banks to a situation in which they engage in share buybacks rather than M&A because they’re trading below book. But it may be that they trade below book because there’s no M&A.

“As long as banks trade below book, they’re very much incentivized to buy their own stock, and as long as they’re buying their own stock, they’re not going to do M&A,” the banker points out.

Meanwhile, if inflation turns out to be stagflation and more of a cost than a benefit for banks, they’re even less likely to trade above book value.

Governments and many small and medium-sized businesses are much more leveraged post-Covid, especially in southern Europe where the cost of credit always tends to be higher in a downturn.

While large scale losses from Covid haven’t happened yet, it may still be too early to celebrate, says Beck at the European University Institute.

“Policy choices affect how good the recovery will be, which in turn affects how many firms will be over-levered or need restructuring,” he warns.

The claim that higher rates are unequivocally good for banks certainly becomes less credible if you imagine interest rates above 1% or 2%. The widening of Italian and Spanish sovereign spreads against German government debt over the past six months, and particularly since January, already runs somewhat counter to the idea that southern European banks will benefit most from higher rates, especially given how much local government debt banks hold.

Javier Pano, CaixaBank’s chief financial officer, says what he calls “the goldilocks scenario” involves removing negative rates but not raising rates so much that it results in higher credit losses.

“Personally, I think we will have a rebasing effect in terms of inflation because of the extraordinary fiscal and monetary actions taken during the pandemic, but in due time this very high inflation will gradually normalize close to central bank targets,” says Pano.

“Yield curves are discounting rates at 2% or slightly above in the US and close to 1% in Europe. Even at those moderate levels, banks will do very well because it is moving from negative rates to slightly positive. This makes a huge difference for us.”

Perhaps the sector is right to assume the ECB and others will only go a little above zero, precisely because they’re so aware of these risks.

“When you have too much debt, one of the ways to manage the debt is through negative real interest rates,” argues Álvarez, looking at the next five to 10 years.

“Today, roughly speaking, official real interest rates are about minus 5% in Europe and the US. Let’s assume inflation goes to 2% or 2.5% or 3% once we normalize the supply-chain bottlenecks and energy prices. I’m not betting we’ll have positive real rates, meaning 3% or 4%. I’m betting more that interest rates will be 1% or 1.5%, so still negative in real terms but less so than today.”

Regulatory de-escalation

Things are also looking up on the regulatory front, as bankers hope the long post-2008 ramp up in capital requirements might finally be over.

Europe’s imminent implementation of the final version of Basel III looks set to inflate risk weightings in mid to high single-digit percentage terms, according to Mediobanca, compared with expectations of as much as 20% a few years ago.

The Basel III project consumed an average of €72 billion in capital a year between 2009 and 2019, according to BofA research, but if that’s over, higher shareholder payouts could become the norm. The accompanying fall in regulatory risk could then even help keep a lid on banks’ cost of capital.

In terms of balance-sheet risk, the advent of the Single Supervisory Mechanism in 2014 – moving prudential powers to the ECB and away from national central banks – gave way to a rapid reduction in non-performing loans (NPLs) in southern Europe.

According to Intesa Sanpaolo chief executive Carlo Messina, the recently developed NPL secondary market could now remove fee-rich Intesa’s only source of weakness against European peers. The bank’s strategy in early February consequently included a plan to become what Messina called a “zero NPL bank”, thanks to “massive upfront de-risking”.

Higher inflation could translate into higher pay for bankers too, of course. Banks are competing with other industries for the best tech staff and they’re also in a war for talent in wealth management and many other businesses.

Disappointing cost figures put a damper on BNPP's fourth-quarter results, exacerbating those concerns. Still, BNPP chief financial officer Lars Machenil says it is wrong to assume that the benefits of higher interest rates and therefore interest margins wouldn’t amply outweigh the downside of higher inflation in terms of expenses.

“As we foresee that our revenue growth will be higher than our costs growth, one can expect the bottom-line impact [of higher rates] to be positive,” he says.

It is not the time to be planting flags in new countries and expanding in new areas of business, and costs are only going one way

So perhaps getting to book value – allowing more growth and M&A – is achievable. Banks in Europe, after all, have spent the last decade trying to boost the bottom line, aggressively cutting staff and especially bank branches.

Previously, cost cuts have often fallen most heavily on corporate and investment banking, especially at firms like SocGen. Recent business plans, including that of BNPP, are still largely about efficiency.

However, some worry that higher rates will remove urgency from the most difficult part of the switch from branches to digital channels, while also making investment banking seem more affordable.

European banks won’t say they’re going all out in investment banking just because they’re less pressured on bottom line and capital. Yet the last two years of buoyant trading and investment-banking business have boosted banks such as Barclays, which have held onto bigger ambitions in these areas.

Rising inflation in investment banker pay reinforces the logic of investing in simpler balance-sheet businesses as a means of gaining exposure to a European banking rates fillip, according to Jerry del Missier, founding partner of financials-focused Copper Street Capital and former co-head of corporate and investment banking at Barclays.

Rate tightening cycles typically come before a switch in the business cycle, he notes.

“It is not the time to be planting flags in new countries and expanding in new areas of business, and costs are only going one way," he says. "Growing market share in a good business environment for investment banks is very difficult as you can only undercut on price.”

But in retail banking, as in wholesale banking, higher interest margins could make high costs less obvious. Commerz, for example, is especially well-placed to benefit from higher rates because its profit margin is so thin.

Rising net interest income will make more of a difference to banks with similarly high cost-to-income ratios.

“There’s a risk that European banks will slow down their transformation, which will not be good for the medium term,” Mustier warns. “It is much more difficult for a bank to transform, to restructure and take harsh action, when the environment is good. Team members don’t understand and the unions don’t understand, and the shareholders might not understand either because when you restructure, you need to take provisions and take the pain upfront.”

Mustier sees banks becoming like big car companies, sourcing products from an ecosystem of smaller third-party producers, including fintechs.

“Consolidation per se isn’t a panacea,” he adds. “On the merger side, I have not changed my mind. If you have enough critical size in a given country, you should transform and push to grow organically rather than to do in-country consolidation.”

Andrea Enria has voiced similar concerns about profitability since becoming chair of the ECB’s supervisory board in 2019. In a speech last September, he said banks “need to ensure their business-model performance is sustainable throughout the cycle” – including an environment like the one of the last few years.

“For quite some time, many banks maintained wait-and-see approaches, pinning their hopes on a rapid normalization of the interest-rate environment,” Enria noted.

Such worries harks back to the idea that the industry, including supervisors, hasn’t adjusted to a world in which rates are higher. But interest-rate rises will still boost net interest income if banks push harder on fees.

BNPP's and UniCredit’s new strategic plans certainly give no impression they intend to push less hard on fees because of expectations of higher rates.

Higher rates and a more comfortable capital position could now be an opportunity to forge a better future at a time when fintech stocks are on the back foot. Alternatively, the industry could see it as a chance to take a breather and relax a little.

The question is still open, says Matt Austen, head of Oliver Wyman’s financial services practice in Europe.

“Investment capacity has not been the binding constraint in incumbent banks’ digital transformations,” he says. “Legacy technology remains a hindrance, as does a traditional mindset, which emphasizes banks and financial institutions as balance-sheet rather than customer businesses, hence the excitement around the impact of interest rate rates and macro on earnings.”

Making the right calls on rates and credit, and using dividends and capital to drive stock valuations, all feels a bit like financial engineering.

Banks are still insufficiently focused on being useful in Austen’s view.

“That’s not going to be put upon them by a respite from rates or loan provisions,” he says. “If banks want to capitalize on the opportunity, they will need to organize and manage their business in a way that is much more focused on delivering convenience and value to their customers in the same way that tech companies and new entrants have done.”