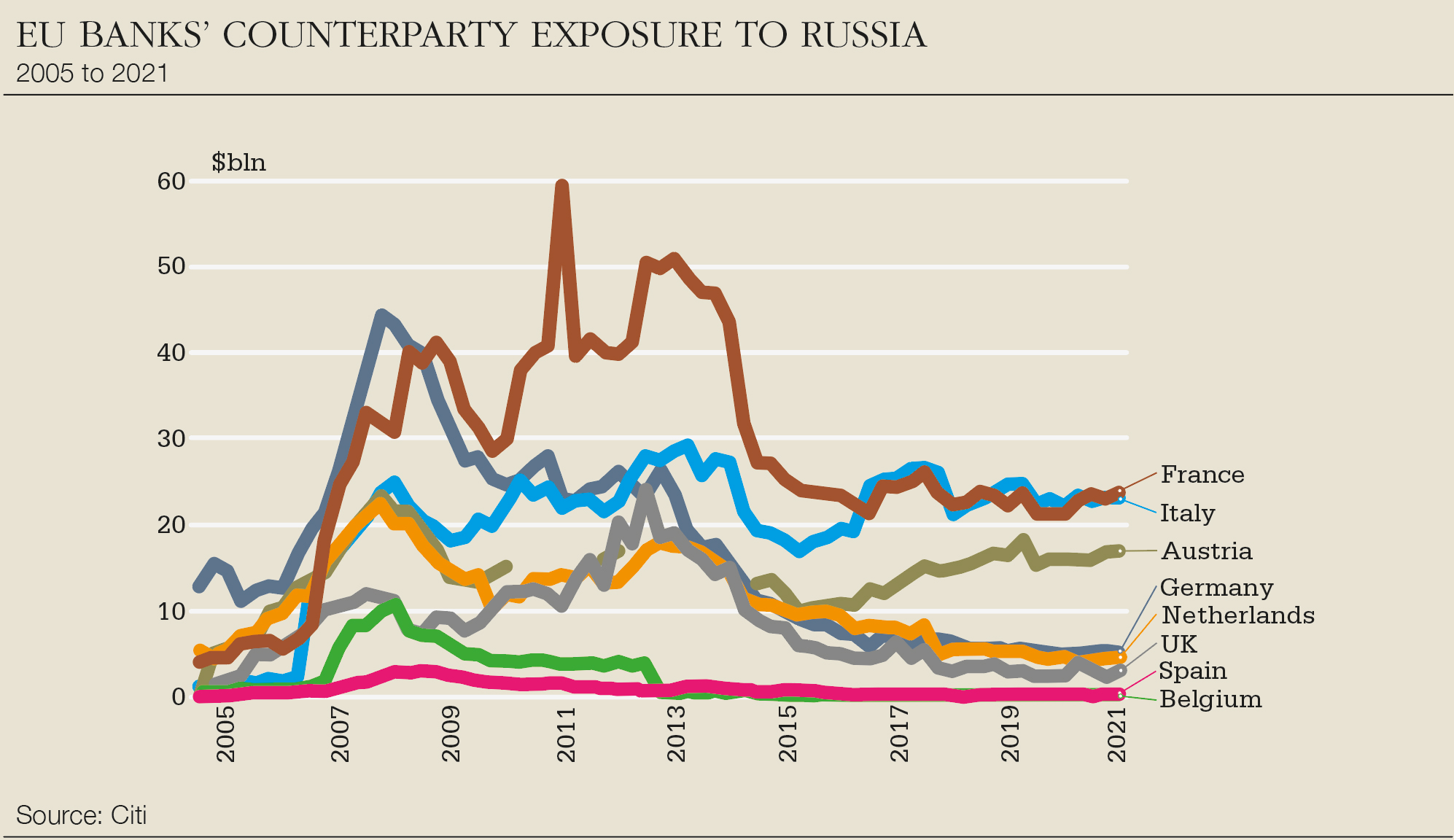

European banks went into the Ukraine crisis with almost $100 billion of claims in Russia, according to the latest Bank for International Settlements statistics. That’s far more than claims from any other region, and it’s almost all in the hands of eurozone banks, led in Russia by France’s Societe Generale, Italy’s UniCredit and Austria’s Raiffeisen Bank International.

These three banks, which control Russia’s biggest foreign-owned banks, could be faced with a grim choice between doubling down and recapitalizing their Russian subsidiary lenders, or abandoning them, much as BP has done with its Rosneft stake.

Neither of these are good options.

Ultimately, the regional economic impact of the war in Ukraine could far outweigh the damage sustained by Western European banks from their exposures inside Russia and Ukraine if it means much higher loan losses in their home countries and a prolongation of negative eurozone interest rates.

Nevertheless, direct exposures to Russia are important, which is why – coupled with uncertainty over the wider economic impact – questions are already being asked about whether or not the European Central Bank could restrict some shareholder pay-outs, as it did in early 2020.

Note that UniCredit’s investor story is predicated more than most on a large buyback programme.

Those banks with big operations inside Russia will now be hoping that the country’s economy and banking system, or at least their bank, can weather the imposition of the strictest sanctions ever imposed on a G20 nation and the hit on the local currency for long enough for the war in Ukraine to reach a diplomatic conclusion.

But these economic and geopolitical outcomes look optimistic. They would be faced with few options if their banks experience liquidity shortages.

Should they throw good money after bad by propping up the bank in the hope of illusive better times? Or do they walk away, as Crédit Agricole did from its bank in Argentina in 2002?

Based on losses in the 1998 Russian financial crisis, Autonomous Research models a 60% loss on European banks retail and corporate loans in Russia and on domestic interbank exposures, with a 15% loss under a less severe scenario.

The 60% scenario would see Raiffeisen take a 13.7% hit to its common equity tier-1 ratio, while Hungary’s OTP would suffer a 5.3% hit. SocGen and UniCredit would take 2.2% and 2.1% hits, respectively.

The numbers are obviously something of a stab in the dark at this stage. It could be 15% and it could be more than 60%. The true levels of exposure, for example in the private-banking and derivatives market, are in any case hard to determine.

Controls

Even if the war in Ukraine doesn’t escalate, there’s little chance of a quick rapprochement between Russia and the European Union. International sanctions are preventing almost all the big Russian banks from transacting internationally, while Russia’s central bank has also had its assets frozen.

Note that the London-listed shares of majority Russian state-owned Sber, previously Europe’s biggest bank by market capitalization after HSBC, fell 74% on the first day of trading after the news that it and almost all large Russian banks would be cut off from the Swift payments system.

At the same time, under new capital controls decreed by president Vladimir Putin on Monday, Russians are now banned from using hard currency to repay foreign lenders. Even after the Russian central bank said this would only apply to new loans, doubt remain about what is allowed – in addition to the wider uncertainty of the impact of the sanctions both Russia and the west have imposed.

Compliance officers will have a hard time greenlighting anything to do with Russia while they work out how to manage the complex implications of all the sanctions. That dynamic could exacerbate the impact on the Russian economy and by extension on its borrowers, especially those with foreign currency debt, which has rocketed in price due to the decline in the rouble. Collateral values have also collapsed.

No one in Europe and the US wants to be seen to assist Putin’s regime in any way.

All this means that the ECB may at some point prefer the walk-away option. Bear in mind the supervisor’s job is to maintain financial stability in its own currency zone, not other people’s.

Exposures

According to Autonomous, for the three banks with the biggest exposures in Russia, walking away would be much cheaper – even if, as the research assumes, they must still take 60% losses on internationally funded exposures.

SocGen would reduce the impact on its CET1 ratio to 0.7%, for example. That is less than the 0.9% hits that Intesa Sanpaolo and ING would take from doing the same thing. It is only slightly more than the 0.6% hit Crédit Agricole SA would suffer.

As Intesa, ING and Crédit Agricole are mainly internationally funded in Russia, walking away wouldn’t make much if any difference to their losses. Raiffeisen, by contrast, would reduce its CET1 hit to 2.2%. For UniCredit, the hit would halve to 1%.

Fitch reckons that even a full write-off of the two banks’ investments in their Russian subsidiaries in an extreme scenario would have a fairly moderate impact on capital at a group level. It estimates that Societe Generale’s consolidated common equity Tier 1 ratio would fall by about 40bp and UniCredit’s would fall by about 15bp.

The problem, though, is that it is much harder to abandon a bank than an investment in the energy industry, such as BP’s Rosneft stake.

Beyond the transfer of know-how and international connectivity, foreign banks in emerging markets seek to benefit from the trust that comes with having a parent in a richer country. If they cut their Russian banks adrift, what are the clients of banks they own elsewhere to conclude about their commitment?

Perhaps clients of other eurozone banks in, for example, Turkey could ask similar questions, given that Turkey’s economic and political situation was until recently far worse than Russia’s.

Whether or not the ECB will care, though, is another matter. For the ECB, indeed, this could be just another reason to rue the driving factor that sent eurozone banks to markets such as Russia in the first place: low profitability, partly because of excessive costs, in their home countries.

Opportunities

Despite the increasingly obvious signs over the past two decades that Putin’s Russia was on a collision course with the West, banks in Europe have continued to tout the country as an opportunity for growth and higher returns.

Raiffeisen is the most extreme example. Russia and Ukraine account for 54% of its earnings. The bank has now put out a statement saying it is seeing deposit inflows in Russia and has said it is not going to walk away. But it is still the only European bank whose reduction in market cap since the invasion hasn’t yet exceeded its potential losses in Russia in Autonomous’ extreme example.

Raiffeisen isn’t alone. As late as last autumn, UniCredit chief executive Andrea Orcel was considering doing a deal as part of the central bank’s sale of top-tier Russian lender Otkritie. Even in mid December, UniCredit’s new strategic plan held up central and eastern Europe as its biggest source of growth.

SocGen’s strategic plans have tended to treat eastern Europe in a similarly upbeat manner, despite the growing risks. It is perhaps no coincidence that SocGen and UniCredit are also among the big European banks with the most questions about the viability of their core-market businesses.

Let’s hope the biggest problem for these banks now is that the absence of Russia revenues will make them look even less profitable in the short term. But there’s no longer any question about whether or not the slightly better return on equity that they had in Russia was in any way worth the risk.

No matter the price, they should have sold out when they had the chance.