The announcement by Silicon Valley Bank that it had taken a $1.8 billion loss on the sale of a $21 billion portfolio of securities triggered sharp volatility in bank stocks at the end of this week, with more than $50 billion being wiped off the share price of the four biggest US banks by assets: Bank of America, Citi, JPMorgan and Wells Fargo.

Shares of SVB were halted early on Friday after falling 68% in pre-market trading. Having failed to raise a further $2.25 billion of capital, the bank is now understood to be looking for a buyer.

Contagion is spreading to banks throughout North America and even into Europe and Asia as investors finally acknowledge the negative impact for banks of rising interest rates: deposit flight and large losses accruing in their accumulated other comprehensive income (AOCI) portfolios.

As I wrote for Euromoney in January this year, during the zero-interest rate policy (Zirp) period, some banks managed surging levels of liquidity and anaemic loan demand by building up big portfolios of bond investments, typically long-dated securities such as Treasuries.

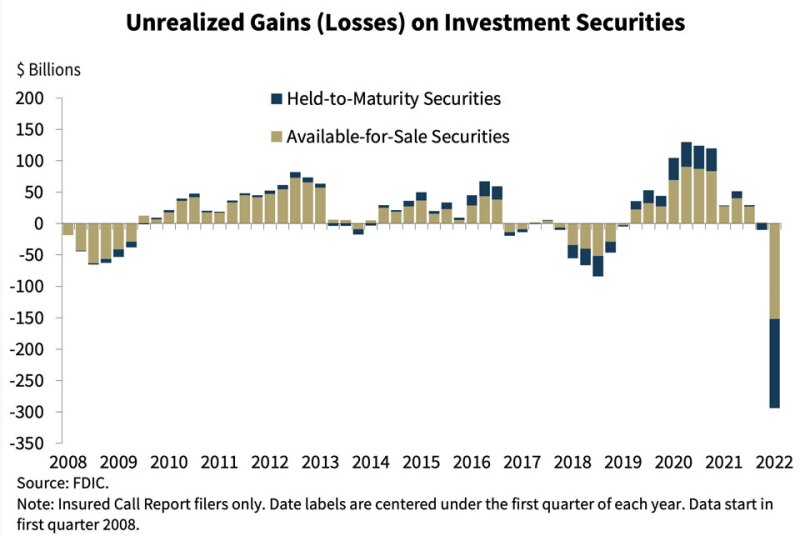

Once the US Federal Reserve started hiking rates, however, the value of these portfolios sunk rapidly under water as they now carry below-market rates.

Unrealised losses on these investments accelerated in the third quarter of 2022, bringing the total to $771.4 billion, according to S&P Global Market Intelligence.

And with the Fed in hawkish mode in the face of stubborn inflation and a persistently strong labour market, it is likely that banks will suffer much more deterioration in the values of these portfolios.

For example, in Bank of America’s third-quarter results, CFO Alastair Borthwick revealed that the bank’s balance sheet had declined by $38 billion, driven by a $46 billion fall in deposits and a $53 billion slump in the value of securities –with quarterly AOCI losses of $4.4 billion.

Precarious situation

The problem for US bank CFOs – as the SVB crisis visibly demonstrates – is that it is a precarious situation to manage. Realising losses by selling AOCI securities and taking the accounting loss has great appeal: take the hit and move forward without the performance drag.

But that now seems impossible, given the precipitous hit to SVB’s share price after it did just that.

Many observers correctly point out the idiosyncratic nature of SVB’s business and to the much safer banking fundamentals of today than was the case before 2008. Banks are far better capitalized and less leveraged than before, and SVB is just a one-off, they say.

But investors have just given bank management a ring-side seat into the risks of trying to tackle these losses.

After all, SVB’s solid tier-1 equity of 15%, its deposit-book loan-to-value ratio of 40% and a 100% coverage ratio offered little in the way of comfort for investors fleeing the scene of the relatively modest loss incurred on the sale of this portfolio.

Any bank planning to raise equity to cushion its balance sheet from AOCI losses will be watching closely.

Shifting losses

The heightened market sensitivity to – and focus on – losses in banks’ securities portfolios will probably mean that the biggest negative outcome of the SVB situation will be an increase in US banks shifting their securities losses from their available for sale (AFS) portfolio and into the held to maturity (HTM) book. European banks are not allowed to do this.

AFS losses get marked-to-market quarterly, whereas there is no requirement for banks to recognise accounting losses on bonds that they have designated they will hold until expiration.

Citi’s CFO Mark Mason has already confirmed that his bank has been pursuing this tactic.

In its first-quarter 2022 results conference call, he told analysts: “If you look at how the balance sheet has evolved, we’ve been moving out of AFS and into HTM over the past couple of years, reducing that as a negative to AOCI.”

Wells Fargo’s CFO Mike Santomassimo has adopted a similar approach, even while AOCI losses still had a negative common equity tier-1 impact at the bank.

Analysts and investors will want to know how large the AOCI losses are; moving these securities into HTM portfolios will simply disguise the scale of the problem

Will more banks follow suit? Analysts and investors will, rightly, want to know how large the AOCI losses are; moving these securities into HTM portfolios will simply disguise the scale of the problem.

This avoids the kind of crisis that has hit the headlines at SVB, but banks will be forced to hold lower-yielding bonds for longer – and below-market returns will constrain margins.

As Euromoney wrote in January, this mix was always going to be problematic for the US banks.

The situation at SVB has just made it far more so.