In BNP Paribas’s elegant Paris offices in Rue d’Antin, Euromoney suggests to the bank’s chief executive a view frequently expressed, particularly in English-speaking countries, that BNPP is Europe’s answer to JPMorgan.

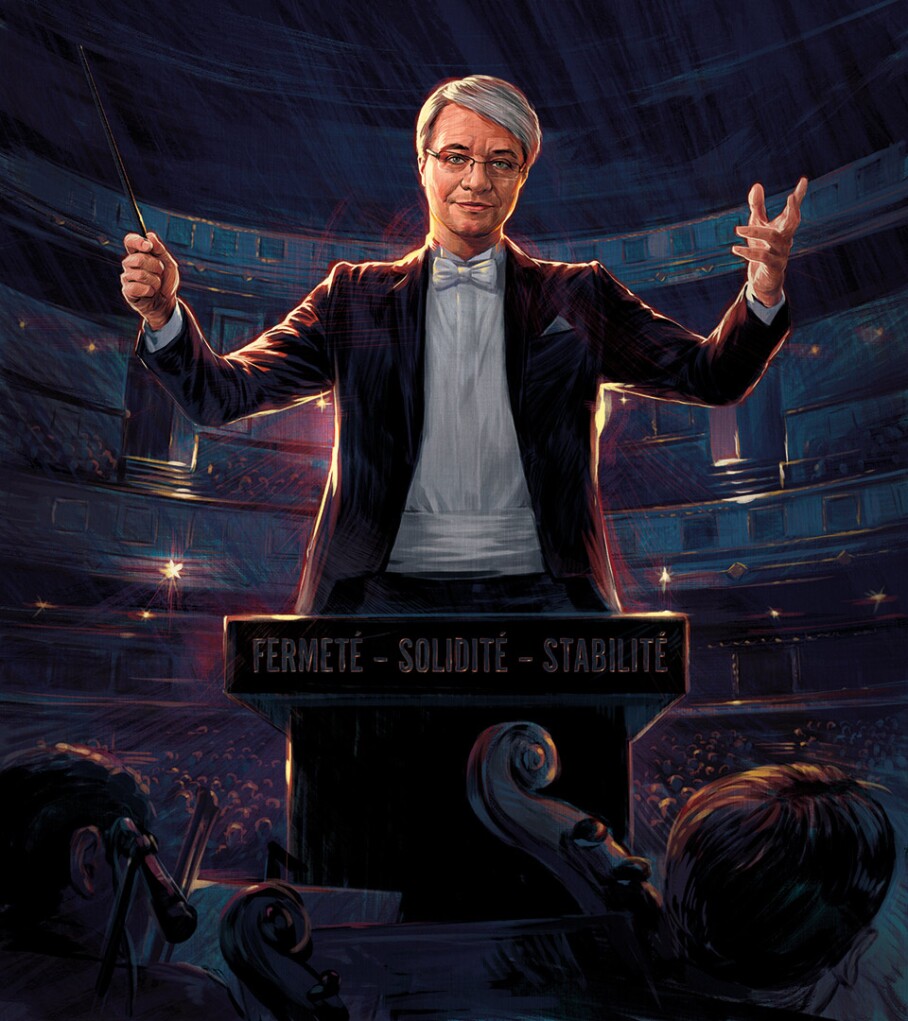

Jean-Laurent Bonnafé’s voice is measured and quiet, but there is no mistaking the flash of frustration. Like others at the bank, he argues that simplistic comparisons to US banks under appreciate the very different context in which European banks operate. This is not JPMorgan.

“We are BNP Paribas,” Bonnafé says deliberately. “These are different operations, different regions and different underlying economies. We have some similar businesses and others that are very different. We have a different approach.”

Shortlisted

The comparison is understandable, of course. BNPP is continental Europe’s biggest bank by assets, with a balance sheet of €2.7 trillion. Clients and investors typically think of it as the highest quality of the large eurozone lenders, much as they do JPMorgan in the US. Both banks benefited from a flight to quality of customer funds after the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank in the US and the rescue merger of Credit Suisse with UBS.

But resistance to the JPMorgan comparison by Bonnafé and his colleagues is equally understandable. Europe, for better or for worse, is thoroughly different to the US. And BNPP is a thoroughly European bank.

In fact, it is all the more European now after completing the sale of San Francisco-based Bank of the West in February 2023, a deal that saw it exit what was by far its biggest retail banking business outside Europe.

Despite BNPP’s well-earned reputation for conservative steadiness, the Bank of the West sale has proved it is capable of decisive action when the time is right. And if the deal had anything, it had good timing – so much so that it will reinforce the reputation of Bonnafé as a dealmaker, particularly as the bank enters exclusive negotiations with French telecoms firm Orange over the future of its two million retail customers in Europe.

There had been questions about Bank of the West’s place in BNPP ever since Bonnafé became chief executive in 2011 at the height of the eurozone crisis and when banks were facing a mountain of new capital requirements. Bonnafé spent much of his early years as CEO deleveraging the bank and getting out of businesses deemed peripheral.

A sale of Bank of the West and BNPP’s other US retail bank, First Hawaiian Bank, might have garnered about $7 billion in total in the mid 2010s, yet Bonnafé and his colleagues thought this was not enough, so they waited. Thankfully, it had more time than many other European banks, which were forced to sell businesses quickly to plug capital gaps.

There is no room to be in businesses where you lack critical mass or profitability

A decade on, BNPP can boast of receiving three times that $7 billion through the 2016 IPO and gradual market sell-down of First Hawaiian, generating $5.5 billion, and then a restructuring of Bank of the West that culminated in a cash sale to Canada’s Bank of Montreal for $16.3 billion.

“The past cycle has been much more about organic growth than the previous one,” Bonnafé says. “You tend to focus on your best businesses because the cost of banking goes up every day, whether it’s from technology or regulation. There is no room to be in businesses where you lack critical mass or profitability. All European banks came to that conclusion in their own way.

“The point is that we have time. We are looking ahead – this is a long-term venture.”

As it turns out, waiting any more time would have been an equally big mistake. The US stock market boomed between mid 2020 and late 2021. Canadian banks were sitting on lots of surplus capital, in part due to Covid-era regulatory restrictions on capital distributions.

Bonnafé and his team agreed the sale of Bank of the West at the peak of the market, getting a valuation of 1.75 times book value when BNPP’s own shares were trading at a discount to book value of about a third. Just a few weeks later, the US Federal Reserve started to hike rates, putting a dampener on regional bank shares and eventually triggering a precipitous crash.

The Bank of the West sale closed barely a month before Silicon Valley Bank failed. Had it been trying to sell the bank now, BNPP might only have got book value if it had been able to close the deal at all.

Instrumental

Bonnafé also pushes back against the idea that the aftermath of the banking crisis would have been the perfect time to pick up troubled regional banks on the cheap, gaining BNPP more of the scale that it previously lacked in the US.

One reason is that BNPP does not have the US political and due-diligence resources of JPMorgan, which is now taking over the remains of another San Francisco-based lender, First Republic Bank.

In Europe, however, BNPP is an increasingly indispensable economic actor – possibly to a greater extent than JPMorgan is in its home market. BNPP has a corporate banking market penetration rate of 64% in Europe, compared with only 49% at its nearest rival, HSBC, according to market research firm Coalition Greenwich.

In North America, Bank of America, JPMorgan and Wells Fargo all have similar levels of market penetration, according to the same research.

When you have a high quality of balance sheet, people trust you

Its importance was especially evident when Covid struck. Amid signs that US banks were pulling back to their home market at a time of stress, BNPP stepped up to help clients ensure they had the liquidity they needed – and not just in France but also in Germany and the UK.

The bank was instrumental in reopening the bond market for corporates and its market share in syndicated loans in Europe rose to roughly double its nearest rival during the first two months of lockdowns in 2020, according to Dealogic.

For many at the bank, this period underscored the problem of relying too much on investment banks from the US – not just from the perspective of businesses seeking to diversify their banking relationships but also in terms of European sovereignty and government policy.

According to Yann Gérardin, responsible for the corporate and institutional banking division and one of the bank’s two chief operating officers, BNPP could only provide this support and remain prudent while doing so because of its development of relationships with institutional investors.

In other words, it was less about risk appetite than a belief in its increased distribution capacity.

“We could never have done the same thing 10 years ago,” says Gérardin. “Thanks to everything we did between 2014 and 2020, we had a different level of expertise and a different level of intimacy with corporate clients and institutional investors.”

Greatest strength

According to Bonnafé, that early Covid period was a test of the bank’s relevance not just in corporate and institutional banking but also in retail, as it had boosted investment in remote banking services over the previous three years.

“It was a testimony of the strength of our business model, of our ability and willingness to serve our clients,” he says.

Now, as new risks have emerged from inflation and the war in Ukraine, stability remains BNPP’s greatest strength. It is why the bank has been better able to provide support to clients than its competitors at times like the start of the pandemic, Bonnafé argues.

We are the bank of the big cities because that’s where affluent clients tend to be located

In a sense, the bank was founded in a crisis. Bonnafé, an avid reader of French history, notes how it grew out of an institution set up in the aftermath of the 1848 French revolution, when the provisional government of the new Second Republic created a Comptoir national d’escompte (CNEP) to provide short-term credit in the ashes of the paralyzed old banking system.

Since then, technology, politics, regulation and competition have all changed. Today, around a third of the bank’s staff work in digital and technology functions; and its inorganic strategy has increasingly focused on technology and new business models in retail – as an Orange Bank deal might show.

But Bonnafé insists this doesn’t fundamentally change the way the bank is run, including the basic determination to serve the economy whatever the economic conditions.

“The characteristic of the past 10 years is that every year or two we face external shocks – the euro crisis, the pandemic, the war and related embargoes, interest rates changing at an unprecedented speed, as well as artificial intelligence or crypto assets," he says. "For us, it’s normal. We go forward through those events.”

Today, BNPP retains a reputation in the European financial industry as having a fundamentally more conservative culture than peers such as Deutsche Bank, Societe Generale and Credit Suisse – firms whose more aggressive investment banking models meant that they have had to retrench or leave the market entirely.

It is obviously a reputation BNPP is keen to encourage.

One of the bank's favourite slides for investors shows how it has increased its tangible book value on a per share basis almost every year since 2008. That is largely because it has avoided asset quality blow-ups and dilutive capital raisings better than other large regional lenders such as Deutsche, UniCredit and Banco Santander, even if it is normally less profitable than the latter.

“This is super-important because investors are prepared to pay a premium for companies that demonstrate predictable shareholder value creation,” says a bank investor at a large US asset manager.

Greater predictability is particularly important at times of uncertainty – like now. Asset quality trends have been remarkably benign for European banks over the past three years thanks to government support measures during Covid and because of the extent to which banks have pushed risk in sectors such as real estate onto asset managers.

But as interest rates continue to rise, reaching levels few believed were possible, more borrowers will surely begin to buckle. Does that create danger for BNPP?

“On average, cost of risk will go up, but we believe that for us it’s going to be relatively minor,” Bonnafé responds, pointing to a level of less than 40 basis points each year to 2025. “It’s not going to be the same for all banks. It will depend on the quality of the franchise and the way you originate financing.”

By way of example, he contrasts his bank’s typical borrower with those in countries such as Spain and Italy, where most mortgage borrowers are on floating-rate deals. A middle-class family there, having taken out a €200,000 mortgage two years ago at a rate of 2% or less, might soon be paying 4% or 5%. That will cause a hit to their post-tax income of as much as €5,000 a year, equivalent to about two months’ take-home pay.

“You can easily understand that in European countries with floating-rate mortgages, borrowers are more exposed when rates climb,” Bonnafé warns.

Affluent clients

BNPP owns Italy’s fifth-largest bank, Banca Nazionale del Lavoro (BNL), so it is exposed to southern Europe. Before BNPP bought BNL in 2006, most of its lending was floating rate, as it is at most Italian banks. But it has shifted BNL to a fixed-rate model as part of its restructuring of the lender over the past decade to ensure the safety of its business.

“The result is that today we do not benefit as much in our top line, but at least we are not putting our clients at risk,” says Bonnafé.

As a group, BNPP is much less weighted to southern Europe than to northwest Europe, especially France and Belgium, where fixed-rate borrowing is the norm. It is also generally skewed to wealthier borrowers.

We don’t own BNP Paribas stock because of the insurance business. We own it because it’s diversified

In France, for example, its market share in what its bankers consider the mass-affluent segment is two or three times larger than its overall market share in retail, which is only in single digits. Its mortgage customers should consequently have more scope to manage the cost-of-living crisis than the wider market.

“Even if the economy is in a slowdown, we have very few issues for these affluent counterparts,” says Thierry Laborde, the bank’s other chief operating officer, in charge of commercial and personal banking. “In pure retail banking, we have limited ambitions in the mass market, but we have a clear vision and development in the mass-affluent segment. Why? Because it’s coherent with our position in corporate and private banking.”

That marks it out from mutual groups like Crédit Agricole, which have much bigger market shares in French retail banking. But for Laborde the calculation is a simple one.

“We are the bank of the big cities because that’s where affluent clients tend to be located,” he says.

Even in its home market, Laborde notes that corporate and private banking accounts for most of its revenues. And Bonnafé says the bank is also extremely selective in corporate banking across Europe.

In Italy, where corporate banking risk costs have previously been so debilitating for the industry, its cost of risk in the first quarter of this year was its lowest since it bought BNL – something Bonnafé argues is due to shifting the business towards larger corporate clients and the better-performing north of Italy.

“BNL used to approach the corporate sector in a way that’s very different to the BNP Paribas model,” says Bonnafé.

The de-risking in Italy fits with a wider strategy of reinforcing the bank’s low-risk profile, a shift that seems particularly fortunate now.

As Bonnafé points out, consumer finance is where lenders often see a higher cost of risk when the economic cycle turns.

BNPP’s consumer finance business, which it calls personal finance, is one of biggest in Europe. This division is moving away from unsecured lending, such as credit cards, to areas such as auto finance, both because the through-the-cycle cost of risk is lower and because it is easier to fund secured portfolios in the capital markets, further reducing the capital cost.

“We’ve tried to push down through-the-cycle cost of risk in personal finance by transforming the platform,” says Bonnafé.

The result is that cost of risk in personal finance fell below 150bp last year, and the bank’s latest three-year plan – called Growth, Technology, Sustainability – envisages this figure will fall to 120bp by 2025. Ten years ago, the bank’s cost of risk in personal finance was around 200bp.

Risk versus revenue

How tech determines BNP Paribas’s M&A strategy

The difficulty of integrating IT systems is one of the main reasons why BNP Paribas is cautious about buying retail banks, especially in cross-border deals. While technological agility has become more important in recent years, integrating legacy systems requires a big effort, even at a domestic level, says Thierry Laborde, BNPP’s chief operating officer in charge of commercial and personal banking.

He points to BNPP’s work in modernizing the IT systems of its bank in Poland after acquiring the Polish operations of Dutch lender Rabobank and Austria’s Raiffeisen Bank International early in the last decade.

“IT is key in our businesses,” he says. “The openness of the IT system is key; the ‘API-ization’ of the IT system is key. If you buy a bank and you have a merger to do, you are too slow.”

The even greater difficulty of integrating retail banking systems across borders is largely why BNPP chief executive Jean-Laurent Bonnafé is sceptical about high-profile international retail bank acquisitions. He thinks the back-office savings mostly won’t materialize.

In previous big cross-border mergers BNPP has stepped back from the wholesale integration of IT systems, including those in France and Belgium following its 2009 acquisition of Fortis, despite the geographic proximity. There is little sign the bank will change this approach.

ING’s attempt to merge its Dutch and Belgian systems when Ralph Hamers was chief executive turned out to be something of a distraction as it had to row back on much of the project.

However, BNPP does have some group-wide IT infrastructure. This includes a long-term agreement with IBM to manage data centres using IBM Public Cloud, helping it speed up its roll-out of new digital services and applications for its retail banks in France, Belgium and elsewhere.

The greater scope to deploy state-of-the-art technology across borders beyond traditional retail banking is largely why BNPP is seeking international synergies across Europe in higher-growth businesses such as auto finance, and in areas of payments like buy-now-pay-later and cash management.

“The key for managing these flows is a very modern and efficient tool for all of Europe,” says Laborde.

Have these moves away from riskier personal finance business come at the cost of profitability? Even if it has meant lower revenues, bank insiders say, that is not necessarily the case because of the higher capital cost of riskier business.

Across the bank, there is evidence of a similar refusal to chase higher returns by taking bigger risks – most obviously, in the greater focus this last decade on Europe and in particular northwestern European countries like Germany.

Contrast Bonnafé’s 40bp with a cost-of-risk target of between 100bp and 110bp at Santander – the eurozone’s second-biggest bank by market capitalization after BNPP. That is mainly due to Santander’s higher risk markets in the Americas, especially Brazil.

BNPP chairman Jean Lemierre says this low-risk culture is also a feature of BNPP’s grounding in Europe because of the region’s greater reliance on bank lending rather than capital markets compared with the US.

“One of BNP Paribas’s strong points, which we pay a lot of attention to, is the high quality of the balance sheet,” says Lemierre. “When you have a high quality of balance sheet, people trust you. You are more fit for the European lending-based model in the corporate sector. You can also grow a strong markets-based business again because clients trust you.”

Lemierre’s argument about lending will perhaps spark memories of how a backlog of non-performing loans in Italy and elsewhere hampered Europe’s economic recovery in the previous decade. But it also points to the risks run up by large European banks that embarked on overly ambitious investment banking strategies, including in the US, only to see the US banks promptly take market share in Europe.

“There’s been massive concentration of market share in global markets,” Lemierre notes. “Many other European banks have reduced their activities in global markets, and part of that is to do with the quality of the balance sheet.”

Diversification

BNPP’s cautious approach is not just about a prudent attitude to specific risks, it is also about diversification, whether that is between corporate and investment banking, retail and other financial businesses or between European geographies.

Corporate and investment banking, quite deliberately, accounts for a much lower proportion of its risk-weighted assets (RWAs), at 33%, than it does, for example, at Barclays with 64%.

“BNP Paribas would be horrified at holding the sort of proportion of risk in the investment bank as Barclays has, as they’ve always thought that diversification brought resilience,” says Alastair Ryan, a banks research analyst at Bank of America.

In corporate and investment banking, RWAs at BNPP are also relatively balanced and more skewed towards global banking (20% of group) than global markets and securities services (13%). Even within global markets, it suffered less than other French banks when corporate dividend cuts in early 2020 caused write-downs for European equity derivatives players – partly because of the offset of a proportionally bigger fixed income business.

France accounted for less than half of BNPP’s retail and commercial banking RWAs last year. France also accounted for a similar proportion of retail and banking revenues (40%) in the first quarter of 2023, thanks to the contribution of retail banks in Belgium, Italy and elsewhere. Across the group, French retail and commercial banking accounted for only 13% of group RWAs and revenues.

Contrast this diversification of risk and revenues to the Dutch banks’ reliance on one small country and one product, mortgages. That focus on domestic home loans became a big problem for Dutch banks when interest rates were stuck in negative territory.

Due to a relatively strong performance in 2008 and after the eurozone crisis, BNPP has been able to keep product factories for things like insurance, asset management and payments, while other European banks – including the Dutch – have had to sell.

That said, insurance and asset management is a less noticeable feature of BNPP than at banks such as KBC or Intesa Sanpaolo – in large part because BNPP is a bigger group, especially in corporate and investment banking. Nevertheless, these businesses have boosted BNPP’s income diversification, especially fees, and their standalone viability arguably matters less than their function inside the group.

Sebastiano Pirro is chief investment officer at European financials-focused asset management company Algebris, which counts BNPP as the top holding in its long-only equity strategy. He compares BNPP’s offerings in areas such as insurance and asset management to Apple Music and Apple TV: they allow the wider conglomerate to increase its per-customer revenues, even if they’re smaller in terms of users and content than standalone competitors like Spotify or Netflix.

BNPP’s asset management, insurance and payments businesses may sometimes be more functional than exceptional, but they are still an important part of the overall equity story.

“It’s a good mix of businesses under the same umbrella,” says Pirro. “We don’t own BNP Paribas stock because of the insurance business. We own it because it’s diversified.”

Economies of scale

All the same, diversification should not be confused with lack of focus, something that has become particularly important as investors have increasingly favoured banks with more geographically specific business models, which are deemed more efficient and easier to understand.

After the sale of Bank of the West, it is harder to level accusations of empire building at BNPP. Bonnafé fully acknowledges how what he calls the 'rising cost of banking' means economies of scale have become even more important, including in US retail banking. At the same time, European banks have not been able to afford to act as consolidators in the US due to their relative valuations.

“By 2020, Bank of the West was profitable,” explains Bonnafé. “At that moment, we started to see a wave of consolidation in the US. Why? Because the cost of running a bank had become high due to IT investment and digitalization. Either you consolidate or you exit; buying a similar bank would have cost a lot.

“At the end of the day, you need to do a capital increase. This was not possible, so we decided to consider an exit.”

This geographic refocusing has not just happened in the US. BNPP has recently moved to sell its remaining banks in sub-Saharan Africa due to similar concerns about efficiency, including the rising cost of overseeing small and idiosyncratic markets from Paris. It has also streamlined in asset management and insurance over the past three years by exiting countries, terminating partnerships and closing specialty subsidiaries.

Although Bonnafé considers the bank a global leader in creditor protection, it has exited its shareholding in SBI Life in India, sold out of a joint venture in Vietnam and negotiated an insurance sale in South Korea. On the other hand, its asset management division has recently acquired Dutch mortgage lender Dynamic Credit Group and Danish natural capital player International Woodland Company.

It is a similar story in consumer finance. The bank sold its business in Bulgaria to a local subsidiary of Greek lender Eurobank late last year. It is also close to a deal to sell its consumer finance business in Hungary. It is looking to sell its consumer finance businesses in Romania, Czech Republic and South Africa; and there is a sense that other consumer finance sales could follow elsewhere, as the bank refocuses on western Europe – including investing in its auto-finance platform.

“There’s a tendency to concentrate on markets that are more relevant in terms of their size and to which we can add value through integrated platforms,” says Bonnafé.

Nonetheless, BNPP’s diversification in terms of the spread of its services – and geography within its home region – can be seen as a feature of it being such a European animal.

US model

Bonnafé and his colleagues evidently have a lot of admiration for US financial institutions, such as JPMorgan and BlackRock. That admiration is often mutual, like when its post-Covid financing of large clients wowed some peers across the Atlantic.

But there is no question of BNPP building a European version of JPMorgan. Though Bonnafé, Lemierre and the other senior management may bristle at this suggestion, and often seem uncomfortable with the comparison, there are straightforward reasons for it.

A pan-European retail bank would necessarily be more of a patchwork operation than Chase, JPMorgan’s US consumer and commercial franchise.

“In banking, the main driver is the underlying market franchise, and Europe is not a totally integrated market,” Bonnafé points out.

As a result, BNPP’s approach largely consists of targeting regional synergies beyond retail banking, often in activities in which large US banks are not active in their home market, like insurance and car fleet leasing. This is because BNPP finds these types of business easier to run across borders than pure retail products such as mortgages.

Working as one: Bonnafé bangs heads together

As with any conglomerate, one of the biggest determinants of BNP Paribas’s success is its ability to ensure its spread of businesses offers not just diversification but also synergies. Progress on this front is one of the most important ways in which BNPP has changed over the past 10 years, according to its chairman, Jean Lemierre.

“I think this is one of the major achievements of Jean-Laurent Bonnafé,” Lemierre says of the bank’s chief executive. “There’s been a deep change of mindset and in how people work.”

Cross-selling insurance and asset-management products to mortgage and current account customers is, of course, an essential part of BNPP’s retail business, as it is at other European banks. Despite the recurring debate about the demise of bancassurance, growing fees from these businesses remains a focus.

But the greater readiness of investment bankers to work with the private bank, for example, or for bankers in Germany to work with their colleagues in New York, is also vital.

Lately, interdisciplinary work between divisions and geographies has driven the launch of new group-wide initiatives relating to mobility – to do with electrification and the rise of consumer car leasing at Arval – and investment in private assets.

New unit

The group set up a new private assets business unit in December, headed by former head of group strategy David Bouchoucha. Although formally in the asset management division, Bouchoucha aims to bring together expertise in private debt and equity in wealth management and insurance, as well as real estate.

The new unit also aims to work closely with the corporate and institutional bank, and with BNPP’s domestic universal banking networks in countries such as France and Belgium.

Investment bankers’ relationships with the likes of Blackstone are obviously essential for the new private assets push. But the bank’s personal insurance division, Cardif, has also stepped up its investment in private assets. And last year, BNPP Asset Management acquired a majority stake in Dutch mortgage lender Dynamic Credit Group.

Meanwhile, the bank embarked late last year on a 2025 target to generate an additional €1 billion in revenue across the group from mobility. As with the private assets strategy, the mobility target involves ensuring that insurance, leasing and personal finance benefit from corporate and investment banking coverage of car manufacturers and dealers, and vice versa.

Joint venture

Earlier this year, for example, the bank announced a joint venture with Jaguar Land Rover covering continental Europe, spanning consumer finance and areas such as leasing and insurance. The corporate and institutional bank’s longstanding relationship with JLR’s owner, the Tata group, was the origin of the venture.

Yann Gérardin, BNPP’s chief operating officer and head of corporate and institutional banking, points to a similarly wide-ranging relationship with Geely Auto. The Chinese car manufacturer formed a consumer loans joint venture with BNP Paribas Personal Finance in 2015, and in late 2022 mandated the bank for a $400 million sustainable club loan.

“We bring all of the group’s businesses to the corporate client – not just investment banking but securities services, cash management, real estate services, or Cardif, Arval and personal finance,” says Gérardin. “Each one is at the service of the group and its clients.”

In wealth management, there is a similar focus on exploiting the bank’s various divisions, especially in regions where it does not own retail banks, such as Asia.

“Wealth management is at the heart of group synergies,” says Renaud Dumora, deputy chief operating officer, in charge of the bank’s investment and protection services division, and chairman of BNP Paribas Cardif.

“We’re growing quickly in wealth management in terms of our net new cash and client acquisitions, both in our domestic markets and elsewhere, thanks to an integrated model,” he says. "We are benefitting from our domestic bank networks and from the international network of the corporate and institutional bank."

“You have a tendency instead to look for platforms that can be stretched throughout the European area: specialized finance, investment banking, trade finance, cash management, factoring, car finance, consumer lending, securities services, wealth management, asset management, insurance,” says Bonnafé. “All those can be run as global platforms.”

That ability to deploy businesses such as investment banking and leasing in Belgium is, according to Bonnafé, a large part of why its acquisition of Fortis was successful, despite Fortis’s post-2008 weaknesses and even though BNPP has, with characteristic caution, still made no attempt to integrate its core Belgian retail banking platform onto its home-market IT platform.

“Ultimately, we delivered a lot of synergies because we had regional business models that we could leverage on,” he says of the Fortis merger.

The relative difficulty of building continental-scale retail banks is not the only way in which BNPP and other European banks face very different challenges and opportunities to their US peers.

In environmental, social and governance (ESG) matters, governments and businesses in Europe have demonstrated a more urgent desire to move away from fossil fuels than in the US, not least because Europe – unlike the US – lacks large oil and gas resources of its own.

The push for renewables also plays into European bank strengths in project finance. In sustainable finance globally, European banks consequently punch well above their weight. It is one of the clearest areas in which BNPP excels in Asia, for example.

On the other hand, Europe’s capital markets and institutional investor base are far smaller than those in the US. The proportion of US shareholders in European banks like BNPP is therefore far larger than the proportion of European shareholders in US banks, meaning European firms suffer from greater home-country bias, including currency-risk concerns.

From the US, for example, Paris seems uncomfortably close to Kiev.

This partly explains why, as Bonnafé points out, the valuations of multinationals in Europe lag similarly successful peers in the US in banking and other sectors.

But BNPP’s clients – which, unlike its shareholders, are predominantly European – seem to have a different point of view, judging by the bank’s inflows of deposits and assets under management at the peak of the banking crisis this March. The bank’s liquidity coverage ratio increased by 10 percentage points to 139% in the first quarter of this year.

As one European bank investor says, BNPP still suffers from the dearth of investors willing to take long positions in European banks. Despite the bank’s widely acknowledged safety – and a recent increase in its 2025 return on tangible equity target to 12% – the bank was still trading at about a 40% discount to its tangible book value at the time of writing.

Contrast that with the US, where regional banks have suffered widespread treasury losses, face the prospects of higher capital requirements and have asset-quality problems, especially in commercial real estate, and yet are still trading at around book value.

Perhaps US investors judge BNPP guilty by association with those European banks that have frequently posted losses over the past decade – such as Deutsche. But BNPP’s long-term shareholder return has also been far better than the other biggest listed eurozone banks by assets, according to BofA’s Ryan.

Starting on the eve of the 2008 global financial crisis, he calculates a 64% total shareholder return including dividends at BNPP, compared with -12% at Santander and -59% at Societe Generale.

A reliance on US investors also ties in with how Europe’s lack of development in capital markets makes for more ponderous bank balance sheets and a weaker regional base for fee-rich investment banking.

“We are not in the same situation,” says Lemierre, referring to Europe’s greater economic reliance on bank lending. “You cannot compare a European or American bank. You have different systems, different economies and different mindsets.”

BNPP is nonetheless determined to play its part in the continent’s move to a funding model less reliant on bank funding – and therefore one that will be more resilient and agile.

Is the accompanying investment in its markets business out of some sense of inferiority to the US banks?

Gérardin scoffs at that idea. His division would benefit if Europe’s investment banking revenue pool were closer in size to that of the US, but BNPP is today a rare example of a European firm that is holding out against the US banks in European investment banking.

War chest

Bonnafé has learnt a new piece of English vocabulary since the Bank of the West sale: war chest. Proceeds from the sale will allow BNPP to deploy more capital in expanding high-returning businesses, including global markets, taking further advantage of rivals’ retreats.

After an extraordinary share buyback programme designed to neutralize the earnings dilution from Bank of the West, there remains €7.6 billion, or 110bp in capital, from the sale. The bank has slated 20bp of this for organic growth each year between 2022 and 2025 – with only 20bp allocated for bolt-on deals and 10bp to develop what Bonnafé calls “new business models”.

Strategically, however, this is not a big departure.

BNPP has steered well clear of bank M&A deals over the past 10 years. Instead, it has spent much smaller amounts of capital on high-growth new businesses, such as the French low-cost account service Compte Nickel and buy-now-pay-later company Floa – both firms it considers to be new business models in retail, allowing a relatively cheap pan-European expansion from a French base. On the markets side, last year it bought Kantox, a UK-based foreign-exchange hedging fintech.

The bank’s entry into exclusive negotiations in late June with Orange over its European banking business would be its first inorganic move since the Bank of the West deal completed. But it will probably be light on capital and technical complexity because, at least in France, it would be achieved through a referral agreement with its digital offering, Hello bank – an arrangement similar to its referral agreement for Credit Suisse’s prime brokerage clients in late 2021.

The point – and this is very much related to our very long-term outlook – is not to buy a bank, even at a good price

Away from the bank, there are many who think that BNPP has the scope to play a bigger role. It is still “on everyone’s list” of potential consolidators in European banking, according to a senior financial institutions banker in London.

But at the same time, the banker attributes BNPP’s outperformance primarily to its greater capital discipline and stability. And similarly favourable views of BNPP among investors and analysts suggest it is precisely this reticence to do anything other than bolt-on acquisitions that has meant it has avoided the distractions that have hampered the growth in book value at other banks.

Santander’s 2017 rescue of Banco Popular is a case in point. Although initially well received as the nominal price was only €1, it triggered a €7 billion rights issue and involved the complex integration of a previously decentralized franchise that was not an obvious cultural fit with Santander.

One might also compare BNPP’s attitude to its Bank of the West windfall to that of BBVA, which delighted investors when it sold its US retail bank during the post-Covid US stock market boom. PNC completed the purchase of BBVA USA in late 2021, giving the Spanish group $11.5 billion in cash.

A few weeks later, however, BBVA announced it was launching a voluntary takeover bid for the 50.12% stake it did not already own in BBVA Garanti, Turkey’s biggest bank by market capitalization, at a likely cost to its capital of €1.4 billion. As Turkey has since suffered from hyperinflation, it would be hard to say that investment has been a success so far.

BNPP co-owns a Turkish bank, TEB, alongside the local Colakoglu Group. But it has been far less ready to deploy more capital in Turkey than BBVA, which has a higher group-wide cost of risk than BNPP. The group’s exposure to Turkish counterparties represents only 1.1% of its total on- and off-balance sheet commitments, while TEB has a loan-to-deposit ratio of 72%.

“Together with our partner, we have deleveraged TEB over the past two years,” says Laborde.

Despite its ownership of BNL, BNPP has stepped back from opportunities to buy mid-tier banks in Italy on the cheap as part of consolidation in that market over the past five years – unlike Crédit Agricole. It has also avoided acquisitions of northwest European banks that investment bankers identify as candidates for cross-border mergers, notably ABN Amro and Commerzbank.

Has an excess of caution meant that BNPP has missed valuable opportunities to swoop on troubled rivals? Lemierre and Bonnafé think not. Lemierre dodges the question of Commerzbank’s relevance to BNPP’s strategy of growing in northwest Europe. Its acquisition of the prime brokerage divisions of Credit Suisse and Deutsche has, after all, seen it benefit from those banks’ restructurings in a relatively risk-free manner.

Euromoney meets too many M&A bankers, Lemierre jokes.

A lot has changed in banking since 2008, above all in terms of regulation. The Financial Stability Board’s 2011 introduction of capital add-ons for banks deemed more important to the global financial system would make it especially hard for BNPP to justify buying anything more than a mid-tier lender, as it is already in one of the top groups of global systemically important banks.

“The cost of banking today is such is that if you want to enter a new business or a new geography through a large acquisition, you must deliver extremely high synergies and dedicated resources and time, leaving behind your own strategy and business model,” Bonnafé says.

Such high synergies, he adds, are very hard to realize in retail banking across European borders, especially in IT. Because of the difficulty of integrating back-office operations across Europe, Bonnafé reckons a bank in France buying a German bank might get as little as a third of the cost synergies that a Californian bank would achieve when buying a bank in Texas.

Meanwhile, buying a troubled bank on the cheap might involve even more distraction.

“The point – and this is very much related to our very long-term outlook – is not to buy a bank, even at a good price,” he says.

Investment banking: Rankings are a consequence, not a target

Yann Gérardin, one of BNP Paribas’s two chief operating officers and the man responsible for the bank’s corporate and institutional bank (CIB), presides over a division that is now more globally coordinated than ever before.

When Gérardin took over the CIB in 2014, it was essentially organized by region. There were two global business lines in fixed income and equities, which he subsequently merged into one, but the global banking business – where cash management, capital markets, advisory and lending sit – was essentially organized by region.

He tweaked that over time to introduce a global governance structure, but reaching consensus was still laborious. However, with the businesses themselves performing better, the benefit of closer links globally became more obvious.

And so, in 2022 he made each business explicitly global. Doing so not only brought the regions closer together but also made it simpler for each global business to interact with another.

“The global structure I put in place last year was to allow us to connect better, to better leverage the regions and work on the corridors between cities,” says Gérardin. “We have this spider’s web vision of the business.”

BNPP’s management makes much of its European roots and resists trite comparisons with leading US banks, arguing that the main markets that they operate in are so radically different as to make such comparisons pointless.

But while the bank is proudly European, that sentiment should not be mistaken for a lack of global ambition. Much of what Gérardin has been doing for the past 10 years has been working up to a point where that global ambition can find full expression in the corporate and institutional banking division.

“More global banking was a mandatory step in the vision that I had years ago, so it was always more a question of when not why,” he says.

The US is a good example. Since BNPP sold Bank of the West to Bank of Montreal in early 2023, its US operations are now effectively the corporate and institutional banking division. Reflecting that change, Americas CIB head José Placido was made chief executive of BNP Paribas USA in April, with former chief executive Jean-Yves Fillion moving into a vice-chair role handling the firm’s most strategic clients in the region.

Gérardin is gradually adding to the CIB in the US, but he is not deviating from the franchise’s essential purpose, which is to accompany the bank’s European clients who have interests in the US and vice versa. He is not about to try to compete with the US banks for purely domestic activities on their own turf.

However, what he does want to do, is get more recognition – and more fees – for the role that the bank plays. One example is his recent move to appoint a head of equity capital markets in the US. Evan Riley is joining from UBS, reporting to Christopher Blum, who heads corporate finance for the Americas.

“As far as I am concerned, we were not getting our fair share of fees for our role of distributing stock to Europe and the rest of the world,” says Gérardin. “Additionally, with a bigger ECM setup in the US, we can show that we have the capacity for a European corporate that wants to list not in London or in Europe but in the US.”

This move – which is in part a response to the trend for European companies to choose precisely that listing route – is effectively designed to capture a better share of a pure US deal and of a European deal taking place in the US.

And at the same time, both in ECM and DCM, the more that BNPP can help US clients tap European markets, the more likely it is that those same clients will reward the bank with more business in the US.

Dramatic rise

In 2016, BNPP struggled to make the top 10 in the European investment banking fee rankings. In some products, like ECM, it sometimes ranked even lower and for many years was not even the leader in its home market.

That situation has changed dramatically now, with the bank now a top-three investment banking firm in Europe. It has long been a leader in bonds and syndicated loans in euros, but it is now also the leading European house in ECM, including equity-linked, behind only Goldman Sachs.

What has changed?

“Everything,” says Gérardin. “It has to be a machine where everybody works together to push in the same direction in the service of the bank. This happens when you have strong country heads and strong coverage teams in each of the countries – and when Exane is more integrated into BNP Paribas.”

That last point is critical. BNPP had for many years operated a joint venture with Exane on equity sales, trading and research. But the market often struggled to make the connection with BNPP. There were occasions when clients commented to bankers that they could not mandate the firm because of its lack of research, not understanding the resources that BNPP had access to in Exane.

In March 2021, the bank announced it was buying out the joint venture and integrating Exane wholly.

In advisory, the journey is at an earlier stage. According to the Dealogic rankings of all completed M&A deals involving either a buyer or seller from western Europe, BNPP ranked eighth in 2022, its highest-ever position.

Gérardin is fairly relaxed on the ambition here: top five within a few years would be good, but “we are not going to rush.”

And there are other things more important than rankings.

“The ambition is to be relevant, to be in a position to help our clients all the way from cash management to M&A,” he adds.

Do league tables really matter at all? Gérardin flips it around.

“For me, a ranking is not a target, it’s a consequence. We stay focused on business, which is reflected in the moving up of various rankings year after year.”

In other words, he is not getting up in the morning obsessed about being number three instead of number four and is not going to sacrifice business logic to achieve it.

Looking at it this way is a natural evolution of the overall approach, which is to ensure businesses are aligned to be able to work closely together. And Gérardin is at pains to remind Euromoney that at BNPP his corporate and institutional banking remit goes well beyond advisory, capital markets and sales and trading.

The bank is a European leader in cash management and securities services – and the latter business in particular has done remarkably well under the leadership of Patrick Colle. It was a €1 billion unit at the time of the global financial crisis; it clocked up €2.5 billion of revenues in 2022.

“We will pitch with equal passion for a cash management RFP [request for proposal] or a custody mandate in securities services, because this will lead to the FX deal or M&A of tomorrow,” he says.

Meanwhile, BNPP's global markets business has soared since a post-crisis low in 2018 – revenues were nearly €9 billion in 2022, up 83% from that low and second only to the bumper year of 2009. The recent performance has at times attracted the assumption that the business must be taking more risk as a result. Gérardin is frustrated by that kind of talk.

“This is not the reality,” he says. “Our risk is lower today because the business model has shifted from a highly structured static balance sheet to a very fluid short-term flow business, in addition to a very strong and diversified client franchise.”

In 2016, when global markets revenues were €5.6 billion, the bank’s average quarterly value-at-risk was €34 million. In 2022, with revenues of €8.7 billion, it was €33.5 million.

And Gérardin notes for good measure that the first thing he did on becoming head of corporate and institutional banking in 2014 was to cut the balance sheet by €200 billion.

Economic evolution

Much of the way that Gérardin thinks about what kind of corporate and institutional bank BNPP needs is governed by how he sees the job of financing the European economy will evolve in the coming years.

In this respect, he unsurprisingly echoes the thoughts of the bank’s chief executive Jean-Laurent Bonnafé and chairman Jean Lemierre. But he also reflects the views of continental peers like Christian Sewing, the chief executive of Deutsche Bank.

What they all agree on is that if it is to continue to support the region’s companies and institutions – particularly as they try to adapt to the challenge of a changing climate – the European economy must begin to look more like the US economy. That is, it must be increasingly financed by the capital markets not by banks.

The reason is simple: banks will not be able to provide the necessary level of finance, particularly considering that their regulatory burdens are unlikely to decrease in the future.

While the continent waits for capital markets union to make progress, the region’s corporates are staring at a future whose financing needs are set to get ever more burdensome, particularly given the need for energy transition. Private markets might be expected to play an ever-bigger role, and banks must respond to that.

“Banks will have to participate in the financing of trillions of dollars to support the transition, but obviously the balance sheet of the industry cannot fulfil the magnitude of that request, so there will be a need for private debt,” says Gérardin.

“What we have created within BNP Paribas is the framework for that, the connections between our corporate clients’ financing needs and our institutional clients’ investment needs.”

It is a similar story with private equity investments, where BNPP is working harder to introduce its ultra-high net-worth clients to private equity companies. At the same time, it is getting unlisted companies in front of the bank’s family office division.

This is part and parcel of the same overall philosophy: that the bank must on the one hand increasingly focus on bringing the clients from one business line into contact with those from others, and on the other hand must also adapt its business to better meet the challenges that its clients will face over time.

The future financing requirements of European corporates – and the difficulty that the banking sector will have in meeting those needs while dealing with regulatory requirements – mean there is no alternative to doing this.

“Ten years ago, all these midcap companies across Europe relied on balance-sheet financing only, and in 10 years’ time it will be high-yield bonds,” says Gérardin. “This is the mechanical logic of how we think about developing our business – it is to be able to help our clients finance themselves in the future.”