A year has passed, and we are still learning lessons about the deposit runs that began in March 2023 at US regional banks sitting on large unrealized losses in bond portfolios funded by flighty and uninsured wholesale deposits.

Those runs led to the sudden collapses of Silicon Valley Bank, Signature Bank and First Republic Bank. A recent study, only released in May 2024 by the New York Federal Reserve and using high-frequency interbank payments data to trace deposit flows, now identifies another 22 larger regional banks that suffered a run, far more than realized at the time.

Shortlisted

- Bank of America

- JPMorgan

The only reason they didn’t collapse is because the Federal Reserve quickly set up the Bank Term Funding Programme to ensure banks could rapidly monetize assets to raise cash to meet withdrawals.

It had learned a key lesson from the global financial crisis (GFC) of 2008; in an emergency, be fast and decisive. Once depositors know they can get their money out of a bank, they soon stop asking for it.

But the panic spread to Europe, where it quickly focused on global banking’s weakest link, Credit Suisse. This was a global systemically important bank (G-Sib) whose problems were all-encompassing and glaring.

If there is a lesson still to be learned here, it is that Credit Suisse should already have been dealt with by the authorities. The Swiss financial market supervisory authority (Finma) could only write stern letters, which the bank chose to ignore. This was close to de facto regulatory forbearance. When Credit Suisse repeatedly had to raise outside capital that it could not generate a return on above the cost, and when even its best business turned loss making and clients fled, Finma could not force Credit Suisse to devise a recovery plan and stick to it.

After management upheaval, the disasters of Greensill and Archegos, endless restructurings and capital raising, wealthy customers began pulling their money out at an alarming rate in October 2022.

It was now clearly a problem that needed to be worked out – either pushed to an acquirer such as Deutsche Bank or UBS, or temporarily nationalized – and the sooner the better. Instead, Credit Suisse was allowed to limp on until March 2023.

Credit Suisse was not a gift that was given to us. It is a prize that still needs to be won

Sergio Ermotti, UBS

When the final crisis came that March and it turned to the country’s central bank for emergency liquidity, a short-selling attack on Deutsche saw its credit default swap spreads shoot up and its share price sink.

In the absence of earlier decisive action to deal with Credit Suisse, the cracks in the global banking system now began spreading.

The award for the world’s best bank this year goes to UBS, for three reasons. First it was strong, well-run and stable enough to play the JPMorgan role in Europe and prevent a systemic breakdown. Second, during a fraught weekend, it played its hand supremely well and developed a solution that calmed both the market panic and its own shareholders’ concerns. Third, in the months that followed, it quickly completed the initial repairs on its damaged rival, regained client trust, gave many Credit Suisse bankers still running the institution hope that there was a future, made important strategic decisions, ran down non-core assets and cut costs.

That weekend saw a circle being completed.

Doing a UBS

UBS, the saviour, was a bank that had to be rescued by the Swiss state in the GFC. It then brought in new management, ironically from Credit Suisse, to stabilize it and subsequently re-engineered its whole business model.

“Doing a UBS” became a byword for wholesale retreat from investment banking. Senior executives at other firms would reassure Euromoney, when they were trimming businesses, that they were not doing a UBS. When it became clear that chairman Axel Weber and chief executive Sergio P Ermotti had steered the bank on the right course, bankers began to tell us that they were, in fact, doing a UBS.

Ermotti, chief executive during that restructuring and now back in that role, thinks back to the aftermath of the GFC, in which UBS lost some $200 billion of client assets, and puts the logic simply – and in so doing explains how the remnants of Credit Suisse will now be run.

“There is nothing like a near-death experience to teach you vital lessons,” he recalls. “Our capital had been misallocated, with over half going to an investment bank that delivered fewer than 30% of our profits.

“I said: ‘We are recognized as a world leader in wealth management and the leading bank in Switzerland. Let’s put a clear emphasis on businesses where we are a leader. There are some areas in investment banking where we can compete and also serve our wealth clients, but we will devote a maximum of one-third of our capital to it, and investment banking must earn a return above the cost of that capital.’”

It sounds so obvious now, but at the time this felt like radical thinking. Watching from Wall Street, Colm Kelleher, then running investment banking at Morgan Stanley, was surprised.

“It was very bold. I remember thinking: ‘Why has UBS gone so far?’” he recalls. “It still looked like investment banking would regain the multiples it once enjoyed. But it never has. So this was prescient.”

In the transformation that followed this decision, without raising a single cent of outside capital, UBS more than doubled its common equity tier-1 ratio from around 6% in 2011 to 13% in 2020, paid out over $20 billion to shareholders and another $14 billion to settle litigation.

From 2015, Credit Suisse had looked like it might be an attractive partner for another bank. But it was a deteriorating franchise. And then in October 2022, it was obvious that the proverbial had hit the fan

Colm Kelleher, UBS

Looking at the period from 2012 until the end of 2022, it generated $50 billion of organic capital. It was able to do all that just by concentrating on its strengths.

Then, at the critical moment in March last year, UBS emerged robust in terms of capital and liquidity, sustainable through its dependable profitability, well-managed and credible. UBS was able to rescue another G-Sib bank – the first and, so far, only time one has been taken over – and so contain the panic and stop it from spreading through the global financial system.

It was like saving a sinking ship. UBS lashed Credit Suisse to its side, rescued the passengers and some of the crew and now, in mid 2024, with the legal entity mergers proceeding that will allow systems integration and client transfers, it is cutting the ropes and allowing what’s left of the wreck to sink.

We will never know what might have happened to the Swiss, European and global banking systems if UBS had not been there.

“It was not quite as horrible as 2008, but it had the makings of a full-blown crisis,” Kelleher, now chairman of UBS, tells Euromoney. “When I got the call on March 15, 2023, Silicon Valley Bank had gone. Signature bank had gone. Banks with between $50 billion and $250 billion balance sheets were getting whacked. First Republic was teetering. And Deutsche Bank came under pressure as well.”

Hitting the fan

Kelleher had been hit hard by the GFC when he was chief financial officer as well as co-head of corporate strategy at Morgan Stanley. The Wall Street firm only just survived the funding runs that accelerated after the collapse of Lehman Brothers in September 2008. Mitsubishi UFJ agreed to invest $9 billion for a 9.9% equity stake. That came just in time. Another day or two and Morgan Stanley would probably have ended up as part of JPMorgan.

Kelleher now had a minute’s shock at the memory of that trauma. He realized full well how serious this was.

“The contagion,” he says, “had begun.”

Shocked he may have been, but Kelleher was not surprised.

He had succeeded Weber in the spring of 2022. The chairman of a Swiss bank is responsible for strategy and, although the Swiss do not use the title, the role would be described in the Anglo-Saxon world as executive chairman.

He worked on his relationship with Ralph Hamers, the still newish chief executive who had replaced Ermotti after he had rebuilt UBS. Hamers was renowned more for his prowess in digital banking than for successfully running a global wealth manager or an investment bank, and Kelleher quickly brought in outside counsel.

Ermotti had left UBS in good shape, but the chairman needed advice on how to respond to the unfolding calamity at Credit Suisse.

“From 2015, Credit Suisse had looked like it might be an attractive partner for another bank,” says Kelleher. “But it was a deteriorating franchise. And then in October 2022, it was obvious that the proverbial had hit the fan.”

Credit Suisse had had a good financial crisis. Perhaps because it had survived, it failed to learn key lessons and fell under the sway of its traders once again.

In 2015, Tidjane Thiam took over as chief executive and sought to raise capital, reset strategy, curb the traders’ influence over the whole group, deal with legacy legal liabilities and re-energize the Swiss domestic business. This he did with some success, as Euromoney recognized in a detailed examination in 2018.

Across the banking industry many sources identified one key mistake. He regionalized the organization to put powerful local executives closer to ultra-high net-worth clients. Thiam would say that this made perfect sense to him even if no one else in the industry agreed. But you cannot regionalize risk management. And while the culture of being a bank for entrepreneurs may have initially been healthy, it went astray.

The next five months are important for the integration. And we need to look beyond the integration at what comes next as UBS once again resumes its growth story

Sergio Ermotti

Leaks of previous discussions about a rescue merger deal, following the ouster of Thiam at the start of 2020, had alarmed some UBS shareholders. They worried that their bank might be poisoned if it swallowed hidden litigation risk or other toxic exposures along with whatever good could still be saved from its great Swiss rival.

A number had written to the new chairman warning him not to do a deal with Credit Suisse or he would suffer the consequences.

In any case, the Swiss authorities had long favoured maintaining two large banks, so it seemed likely that Credit Suisse would fall to another partner, even a non-Swiss bank, that would maintain it as a standalone Swiss entity. The rumours suggested Deutsche, even though the German national champion was grappling with its own problems.

UBS had to consider how it might respond to any such sale of Credit Suisse to another competitor.

Come that fateful weekend, the options for the Swiss government, the Swiss National Bank and Finma had narrowed: take Credit Suisse into temporary state ownership, put it into resolution or do a deal with UBS on its terms.

“Resolution would have been possible,” says Kelleher. “This was also confirmed by various authorities. Credit Suisse certainly had enough loss-absorbing capital. But there would have been very considerable contagion and second-order effects.”

We will never know what might have happened. But one thing was clear: if there was no credible solution before markets opened on Monday, March 20, there would be carnage.

Deal of the century

The story of that weekend does not need retelling. But one aspect stands out. The delusion that Credit Suisse could survive on its own continued to the final minute of the 11th hour. Its senior executives were in no rush to open their books to UBS even though Credit Suisse was being propped up by emergency liquidity from the Swiss National Bank.

They tried instead to put a deal together with BlackRock. But it did not want to buy the whole bank, only pieces of it.

One of several outside advisers Euromoney has talked to who worked that weekend says: “Their attitude was: ‘Oh, this is a juicy looking corpse. Perhaps we could have the liver.’”

Credit Suisse also hoped to structure something with the Saudi investors who had supported its capital raise at the end of 2022, even though it was a comment from Saudi National Bank that regulation forbade it from taking a further stake that had prompted the final deposit flight that brought Credit Suisse to the point of non-viability.

Reassured that auditors had been over the numbers prior to that December 2022 rights issue from Credit Suisse; confident that they understood the toxicity of its investment bank and the problem lending it had done in wealth management; and believing that the Swiss domestic bank at least was solid, UBS was now able to set terms that none of its own shareholders could object to.

It wanted access to central bank liquidity, to a loss-sharing agreement with the Swiss government – because UBS only had three days to mark toxic assets to market and read files on litigation risks that had not been publicly provisioned for. And it required a free pass on any competition issues.

Oh, and there was that whole weird thing with the additional tier-1 bonds.

It got everything it wanted. There could be no waiting for niceties such as requesting votes from either side’s shareholders. The Swiss government passed an emergency ordinance. And that was that.

It has been called the deal of the century.

Ermotti, who returned soon after to see through the very deal he had previously explored during his first stint as chief executive, corrects Euromoney. It may yet prove to be the opportunity of the century. But that remains to be seen.

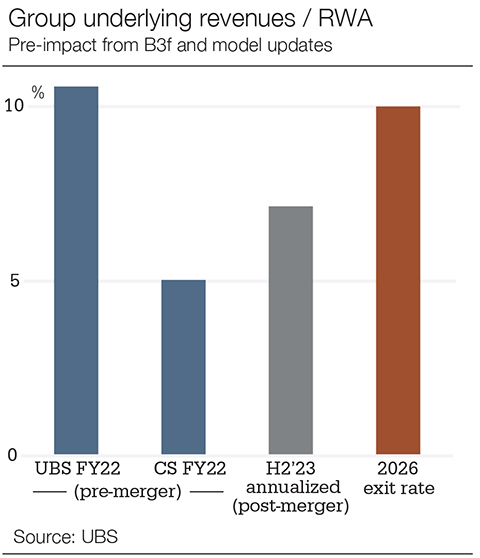

“This was not a gift that was given to us,” he says. “It is a prize that still needs to be won. We had to absorb losses, and now need to recapitalize and restructure parts of Credit Suisse. As a next step we must create the necessary synergies that will make us as profitable as we were before the acquisition, only by 2026 and 2027.”

If it succeeds, by the end of 2027, it will be producing the same levels of profitability but at a much bigger bank.

Call of duty

Getting Ermotti back was crucial, and Kelleher knows it.

The former chief executive felt a call of duty and of work left unfinished. He had come close to doing a deal in 2020.

“We did deep dives on Credit Suisse every six months from 2016 onwards,” Ermotti recalls. “We knew that if they ran into trouble, it would affect us too, either through tougher regulation or through a bigger, stronger competitor taking them over. By 2020, it was clear to us that they did not have a viable strategy. Unfortunately, clear signs were ignored by the board and senior management of Credit Suisse as well as many other stakeholders.”

Some at Credit Suisse saw the wisdom of negotiating a deal with UBS when Thiam left. But Thomas Gottstein had done a good job running the Swiss bank and when he got off to a good start during Covid of channelling state support to Swiss small businesses, his backers made the case that he deserved a chance.

During the pandemic, the underlying structural weaknesses were set aside. The notion persisted that Credit Suisse could muddle through on its own or at least get its stock price back up to the point where it might extract better terms. Here, after all, was one of the largest wealth-management franchises outside the US, now trading at a substantial discount to book.

Then came Greensill and Archegos. Failure to strike a deal earlier allowed UBS to dictate terms in March 2023.

There is a nuance on having sufficient capital for resolution mechanisms to work. Credit Suisse had enough capital but not in the right places. Because of regulatory forbearance, Credit Suisse had been getting away with it

Colm Kelleher

The returning Ermotti was able to draw on his experience from re-engineering UBS in 2012 and after. He was not unduly worried by the ruinous investment bank. And neither was he surprised that a tweet about Saudi National Bank not being in position to inject more capital triggered the final implosion.

“When you are very sick, it can be a minor cold that finally carries you off,” says Ermotti.

In the first minutes after the financial markets opened on March 20, 2023, UBS’s stock sold off sharply until a big investor, believed to be a sovereign wealth fund, bought in. Then the stock rallied hard for most of 2023.

Investors and regulators outside Switzerland embraced the deal. The country’s position as a global centre of wealth-management expertise had come under threat. To many in the industry insulated from direct exposure, Credit Suisse had become a laughingstock.

Now, thanks to determined and brutal decision-making in the midst of the crisis, Switzerland’s position as a financial centre was validated. And UBS had the perfect chief executive to do the initial job of stabilizing the wreck before dealing with the nitty gritty of a three- to four-year integration.

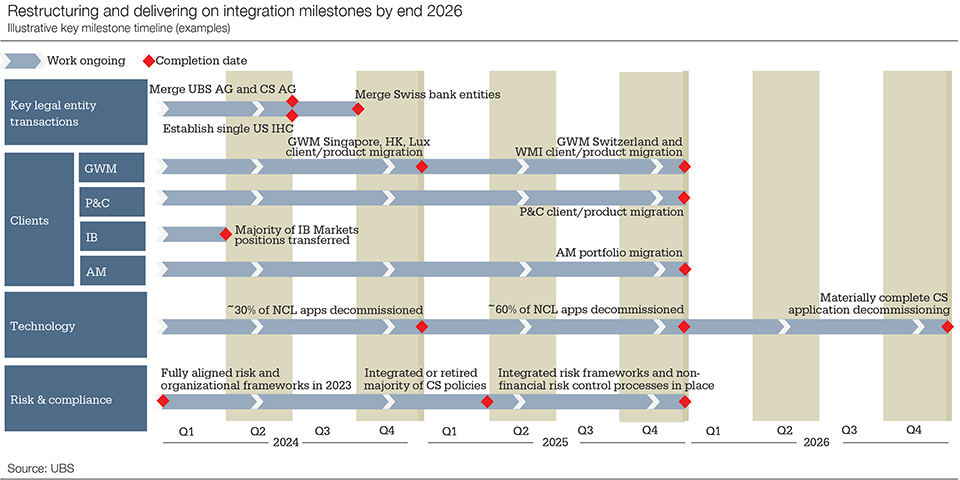

By the time Euromoney sits down with Ermotti, on a hot early summer morning in Zurich, UBS is well into the most difficult part of the process, completing the legal entity mergers and preparing to bring Credit Suisse clients across onto its own systems.

“Later this year, we will start to migrate Credit Suisse clients, first in Luxembourg, Hong Kong and Singapore, onto the UBS platform,” says Ermotti. “So the next five months are important for the integration. And we need to look beyond the integration at what comes next as UBS once again resumes its growth story.”

Large parts of Credit Suisse’s investment bank have already been de-commissioned. UBS has kept its industry groups and the fee-based businesses such as equity underwriting and M&A, but not much else from sales and trading or leveraged finance at the risker end where Credit Suisse had been a leader. When Ermotti wound down UBS’s trading books and heavy capital consuming businesses in 2012, the analogy was of decommissioning a nuclear reactor.

But Ermotti now knew exactly how to do it and got on with it fast, helped by strong markets. He has said that the priority is to get costs down, more so than risk. He had also understood the damage to credibility from asking investors to provide more capital to have yet another go at businesses that did not earn the cost of that capital.

Credit Suisse had done this repeatedly. It was almost addicted to the process.

“You have to analyze and evaluate each business and understand their standalone economics,” Ermotti tells Euromoney. “But you also have to understand that you cannot completely optimize everything because each product is part of a holistic offering to clients.”

What analysts believe is that Credit Suisse had been lending to some entrepreneurs that may not have brought much other business to the bank beyond parking the cash it created by lending to them. UBS does not chase customer relationships based on a single product. Mis-price credit and you can harm clients, leading them to take low-return risks in turn.

“If you have a wealth-management business producing a 15% return, that’s not great,” Ermotti says. “It should be 25%. Unfortunately, in the last couple of years, Credit Suisse had a wealth-management business that was actually losing money.”

Finma must be able to intervene before the instability phase

Stefan Walter, Finma

On the investment bank, with the enthusiasm of the convert, Kelleher has gone even further than Ermotti did back in 2012 and restricted it to no more than 25% of group capital, down from the previous cap of 33%.

“Credit Suisse’s culture in parts of the investment bank was problematic,” says Kelleher. “But there are also parts of Credit Suisse that had a strong culture. CS Switzerland, for example, was very similar to UBS Switzerland. In general, we have taken a lot of measures to implement and enforce our standards throughout the bank. Most of the employees who would have had difficulties with this were already no longer with the bank. And I have been pleased that the people we have got from Credit Suisse are pretty good.”

There was a little shadow play here, in the weeks after the takeover, that UBS might separate the old Swiss universal bank of Credit Suisse into a standalone competitor.

In the heat of battle, it is sensible to retain options. But when the dust settled, UBS soon made it clear that integrating the Swiss bank of Credit Suisse into UBS would be a key part of the deal and an important source of synergies.

UBS has also stopped some forms of Lombard lending in Asia-Pacific wealth management. But the deal may save it seven years on achieving through organic growth its 10-year ambition to become a dominant wealth manager in Asia, a leader in the Middle East and almost as big in Latin America as when it owned Pactual.

There is a lot still to do on the integration across thousands of work streams. But the first year showed plenty of encouraging signs.

Fit and proper

UBS quickly stabilized Credit Suisse’s sinking ship and won back clients that had abandoned it. For 2023, it reported net new assets of $77 billion in global wealth management as well as $77 billion of net new deposits across global wealth management and personal and corporate banking.

The return of the native

UBS was fortunate in 2023. If Swiss regulators had intervened earlier and forced Credit Suisse to do a deal with its rival when it was still a going concern, it might have negotiated better terms for its shareholders than a token consideration. But UBS chairman Colm Kelleher had another reason to celebrate.

“The best thing that happened was getting Sergio [Ermotti] back,” he says. “He has all the experience needed to successfully lead the integration. And Sergio is also well embedded in the Swiss business community.”

Even many of the people at Credit Suisse felt that Ermotti was someone they could work with.

The calibre of the chairman and chief executive of UBS are a contrast with their opposite numbers at Credit Suisse, and the two men dominate the enlarged institution. It is clear that Kelleher didn’t just pick up the phone to Ermotti at Swiss Re on the Monday morning after the takeover of Credit Suisse. He had spent some time on this, knowing how important it was to secure Ermotti’s return and that a sense of duty as well as of business left unfinished would be strong incentives.

Ermotti will be 64 this year; Kelleher 67. So, almost immediately, succession becomes an issue.

Chairmen of Swiss companies are appointed for a 10-year term. Kelleher has already completed two years, and it remains to be seen if he will see out another eight. Even if he serves eight years in total and is still chair in 2030, he may outlast the chief executive he brought back.

“When we hired Sergio, we agreed on three parameters,” Kelleher says. “First, that he commits for three to five years, because that’s how long I thought the integration might take, given my own experience with Smith Barney and that this is far more complex. Second, that he ensures we have solid candidates for his succession. Third, that we improve our wealth-management business in the US.”

Shareholders need to see that future leaders are being prepared. Iqbal Khan, who used to be sole head of the bank’s biggest business, global wealth management, is one obvious candidate to be the next chief executive. The other is Rob Karofsky, who used to run the smaller investment bank.

At the end of May, UBS juggled their responsibilities, making both men co-presidents of global wealth management and giving each responsibility for heading one of the bank’s growth regions.

Khan will move to Asia as president of UBS Asia-Pacific. Karofsky will become president of UBS Americas. That gives the two of them equal status, while ensuring some continuity at global wealth management. Simply swapping jobs would have been riskier and would have looked like demotion for Khan.

George Athanasopoulos and Marco Valla will join the group executive board as co-presidents of the investment bank. Athanasopoulos joined UBS in 2010 and has held various senior roles across the investment bank, including head of global markets from 2020. In addition, he has been head of global family and institutional wealth since 2022. Valla joined the firm in 2023 as co-head of global banking from Barclays.

The board will also have a duty to consider external candidates. As well as the mix of management experience of the prospects to be the next chief executive, another aspect to keep an eye on is the mix of nationalities between future chairman and chief executive. UBS prospered under the chairmanship of the German Axel Weber and Swiss Ermotti – who now works with a chairman who was born in County Cork and spent his career in the US.

If Ermotti does leaves first, it would seem likely that his replacement will be Swiss. It is hard to imagine UBS having another experiment with a non-Swiss chairman and a non-Swiss chief executive. But having both a Swiss chairman and a Swiss chief executive also looks less than ideal for a global bank.

It swiftly returned all that government support, repaying Credit Suisse’s emergency liquidity and voluntarily ending the loss-sharing agreement at the end of August. It made good progress on running down non-core assets and delivered 40% of the promised cost cuts of $10 billion before upping this target to $13 billion by the end of the integration.

“This shows that the authorities made a wise decision in March 2023,” says Ermotti. “The alternative of resolution would have been possible as various authorities, including Finma, have confirmed in their analysis. But it would have destroyed more jobs, eroded confidence in the Swiss financial centre, cost more in goodwill and lost knowledge, and it would also have introduced unnecessary risks to the system.”

Kelleher has his own take on this.

“There is a nuance on having sufficient capital for resolution mechanisms to work,” he says. “Credit Suisse had enough capital but not in the right places. Because of regulatory forbearance, Credit Suisse had been getting away with it. And Finma did not have the necessary powers that some other regulators have, for example in their senior manager regimes. A senior manager regime is about much more than clawing back bonuses. It’s about fit and proper persons.”

At the bank’s annual general meeting in April 2024, Kelleher shared with investors his concern that the wrong lessons are being learned from the extraordinary events of March 2023.

The new head of Finma now wants to look tough by forcing UBS to hold more capital. It is already running a 15% common equity tier-1 ratio underpinning SFr200 billion ($221 billion) of total loss-absorbing capital.

Kelleher goes back to the GFC and a transaction he knows well as an example of the kind of early intervention that might have prevented a crisis.

“After 2008, Citi was not put into resolution. Instead, the US Treasury required it to sell Smith Barney. Recent events have much more to do with resolution mechanisms than capital. Banks now have much more capital and of much higher quality.

“But we should be thinking of a two-step process. Resolution is only the end game. Before that, regulators need the power to intervene early. They don’t need to opine on business models. But they should be able to require credible recovery plans for a bank that cannot earn a return above its cost of capital and that is losing its reputation, long before it reaches the point of non-viability.”

And this is certainly the biggest lesson that Stefan Walter, the new head of Finma, seems to have taken. In his first public appearance at a bank symposium in May, Walter echoed Kelleher’s points, arguing for greater regulatory powers including a new senior-managers regime.

“Finma must be able to intervene before the instability phase,” Walter said then. “Other large bank supervisors such as the Federal Reserve, European Central Bank and Bank of England – but also smaller ones such as in Singapore – already have the powers to implement all of their supervisory measures early, i.e. during going-concern operations. Finma lacks many of these opportunities to act at an early stage.”

Unfortunately for Ermotti and Kelleher he appears also to have learned another lesson. Walter pointed out in May that there will be no other Swiss bank to rescue UBS if it ever gets into trouble – and that takes him back to capital.

“In the case of UBS, we support full capitalization of the parent bank’s subsidiaries,” said Walter, who added that Finma will review the business model and structure of the merged bank with regard to its resolvability from the outset. “In this context, we must have powers to prevent business activities, practices or interdependencies that could hinder an effective resolution of the institution.”

This, of course, is what Finma should have been doing with Credit Suisse. And while it smacks of locking the stable door after the horse has bolted, Walter also emphasized the link between resolvability and capital buffers at the group level.

“The more difficult it is to resolve a bank, the higher the precautionary capital buffers need to be,” he said. “We will keep a very close eye on this.”

Inside UBS, this sounds like an unfair echo of Swiss politicians complaining in parliament after the rescue last year that UBS was now a “monster bank”.

National hero

In 2023, the first ever failure and rescue of a G-Sib bank was the story of the year in European and global banking. It is now becoming more of a Swiss story. The country’s political leaders may reason that the cantonal banks have sufficient capacity to lend to Swiss companies, even if new and excessive capital requirements dampen lending from UBS.

Swiss taxpayers may not realize it, but they indirectly support a large share of the domestic banking industry. Perhaps policymakers should not take too much comfort from this.

“Financing costs in Switzerland for large corporates, small and medium-sized enterprises and households are lower than in many other countries because of average credit spreads that are well below international peers,” says Ermotti. “This is mainly driven by Switzerland’s role as the leading centre for international wealth management.

“The assets from foreign clients booked in Switzerland exceed $2.4 trillion. UBS brings a lot of assets into this country that we can redeploy to support the domestic economy. Half the money that left Credit Suisse went to non-Swiss banks. It is not a theory that this money could leave Switzerland rapidly. It is a fact.”

In a crisis, true power reveals itself. The rescue of Credit Suisse was essential. It was managed in four days by authorities that had previously failed to intervene and prevent it. It was not a democratic process. There were no shareholder or parliamentary votes, which might partly explain some politicians’ hostility and the temptation to blame UBS for a problem it did not create.

The country is proud of national icons like Nestlé and Novartis. A global leader in wealth management that was able to save the country’s reputation and rescue a rival G-Sib looks like one too. UBS still has much to do to make a success of the integration. It is well on track. But if regulators now alter the terms of trade too far, that could be damaging.

UBS was not the villain of the banking crisis of 2023. It was the hero.

The need to fix US wealth management

As it continues with the integration of Credit Suisse, UBS faces another challenge that pre-dates that deal and may continue after it is completed: how to fix its US wealth-management business.

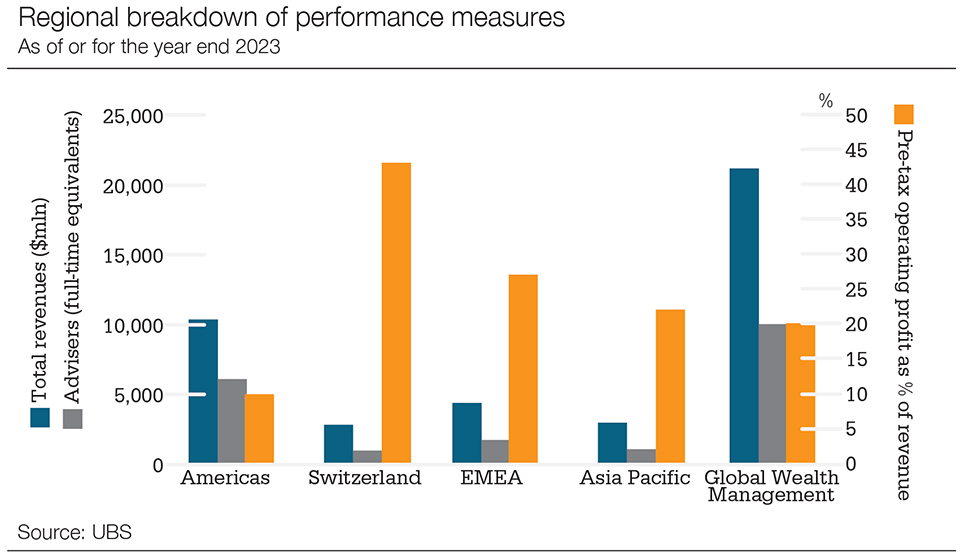

At the end of 2023, UBS employed just over 10,000 financial advisers in its global wealth management division, with 6,100 of those in the Americas. The Americas business shows a higher cost-to-income ratio and lower profit margins than the rest of global wealth management. Operating profit is just 10% of revenues, compared with 22% in Asia Pacific and 27% in Europe, Middle East and Africa.

Getting US margins up to the same level is unrealistic. The US wealth-management business is still different from the rest of the world. It is based on the old commission grid system, which rewards financial advisers for the revenues they bring in and often makes them more like self-employed entrepreneurs working under a bigger brand than bank employees.

And because wealthy clients’ primary relationship is with the adviser rather than the firm, banks must be wary about cutting commissions in case financial advisers are tempted away to other institutions and take a large percentage of the client book with them.

But other firms have moved on and UBS knows full well that it needs to institutionalize those client relationships by making sure clients do more business with the bank rather than just with the financial adviser.

“What makes some US firms successful in wealth management is the liability side of the client balance sheet, not just with Lombard lending but mortgages as well,” says UBS chairman Colm Kelleher. “That leads to more tax advice and inheritance planning. And when a client does a lot more business with the bank, that makes it harder for their financial adviser to take their whole book of business elsewhere.”

Fixing that is obvious but not easy.

“We need a national bank charter in the US,” says Kelleher. “It is amazing that we do not have one.”

UBS chief executive Sergio P Ermotti seeks to manage expectations. It is a reasonable ambition to boost that US wealth-management operating margin to 15% but not the 25% that the US leaders enjoy.

“Most likely we will never entirely close the gap, as we are not a large commercial bank in the US with all of the ancillary products and capabilities that come with that,” says Ermotti. “But we can certainly improve our returns. That is a realistic goal. What I will say is that we are confident that we will maintain our leadership, also in terms of profitability, internationally.”

UBS may enjoy some marginal benefit in the US wealth-management business from retaining the industry specialist investment bankers of Credit Suisse. It was renowned as an adviser to technology companies and so might bring some entrepreneur and growth-company clients selling their companies and looking for a wealth manager. But the bigger potential for growth will come only after UBS fixes margins in US wealth management and builds up on the lending side.

“Scale is important,” says Kelleher. “We first need to grow organically to then be big enough to seize opportunities to further expand through takeovers, if they’re a good fit.”

Outside the US, it was the obvious – and indeed only – choice to rescue Credit Suisse. The ambition is to arrive at a point when the next time a First Republic Bank is teetering in the US, it might fall into UBS’s hands rather than JPMorgan’s.