Do we now also have to worry about French debt sustainability?

There seems to be a pattern emerging here. Back in March, the head of the independent Congressional Budget Office was warning of a potential Liz Truss/Kwasi Kwarteng-style crisis in the treasury bond market if the US does not get its annual budget deficit and total debt burden under control.

Perhaps Phillip Swagel had one eye on what’s looming there in November.

In May, prime minister Rishi Sunak announced a much earlier than expected general election in the UK, which, on July 4, looks likely to bring in a new Labour government.

Of course, the UK has already given the world the painful lesson of what happens when governments ignore the investors that lend them the money and announce tax giveaways to bolster their own popularity: government bond selling in a doom loop; soaring mortgage rates; and emergency measures from the central bank.

No one wants that. A Labour government is unlikely to risk a repeat. Its manifesto promises spending equivalent to a mere 0.1% of GDP to fix the country’s broken National Health Service. If it wins, Labour will stick to the fiscal rules laid down by the independent Office of Budget Responsibility. We can worry another time over how utterly ineffectual those rules are.

Now it is France’s turn.

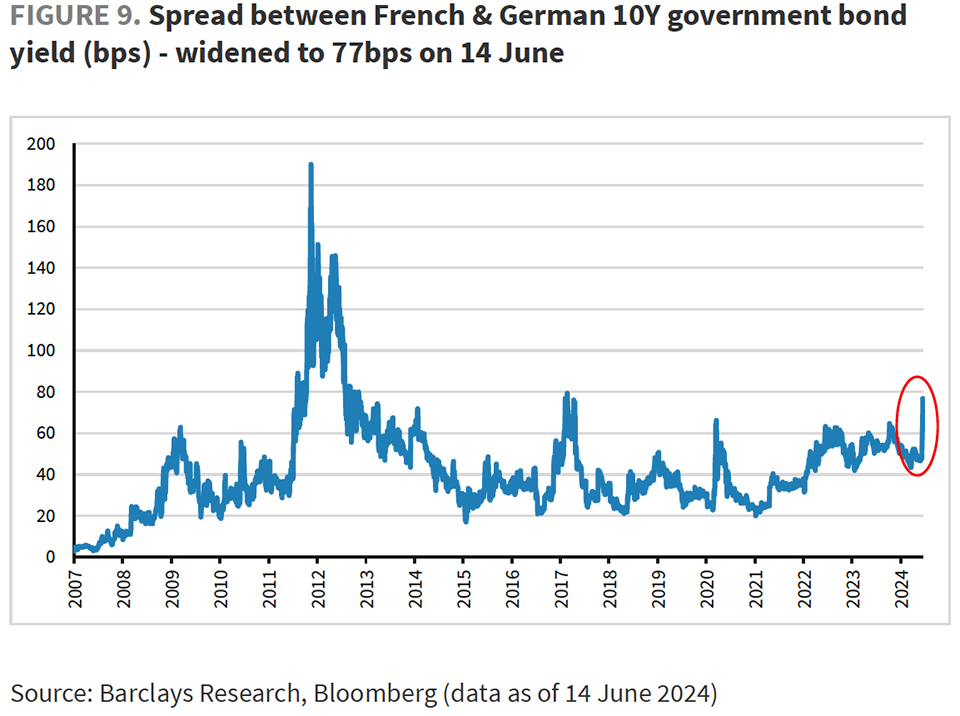

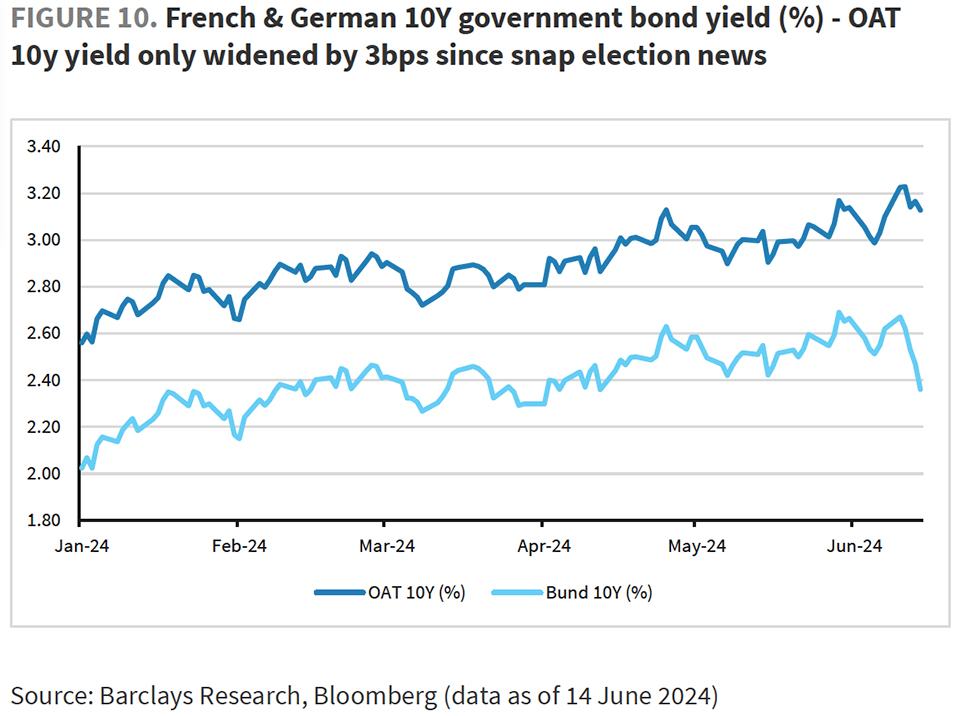

Contrary to what you may have heard, French government bonds did not sell off much in the week after president Emmanuel Macron announced snap legislative elections for June 30 and July 7. Ten days later the 10-year OAT was yielding only 4.5 basis points more than before the news. But German government bonds rallied in that time and so the yield gap between 10-year French and German government bonds widened from 48bp to 79bp.

Sell-side analysts spent last week telling us that relative value buyers would likely come in at much above 60bp.

They didn’t.

There’s an obvious potential problem brewing here. On June 19, as expected, the European Commission announced that it proposes to open an excessive deficit procedure in July against France along with six other member states: Belgium, Italy, Hungary, Malta, Poland and Slovakia.

It’s not a great group to land among, especially when Spain escaped a ticking off. However, this was widely expected and is not immediately threatening. The European Council will no doubt recommend fiscal consolidation to France. It recommended the same to Romania in 2020. Romania hasn’t done much about it since.

The uncertainty arises from the prospect of rumbling conflict between the European Commission and any new government in France that is led by the far-right or the far-left parties. Both are intent on populist policies rather than increasing taxes or cutting spending. There may be a chance of some repeat of the Truss/Kwarteng disaster in Paris. Certainly, Macron’s allies will spread concern about such a prospect.

But at least this time Marine le Pen and the Rassemblement National are not campaigning on an anti-EU ticket or talking about abandoning the euro. And the OAT-Bund spread does not indicate fear of a breakup, as it did back in 2011 and 2012 when it touched 174bp.

It is a worrying sign of vulnerability in the debt capital markets that European bank issuance has suddenly ground to a halt

However, even if is not panicking, the European Commission is worried about French debt sustainability. It points out that while the French government deficit has come down from 6.6% of GDP in 2021, it was still at 5.5% in 2023 and will likely come in at 5.3% this year and 5.0% in 2025. Total general government debt will likely be 113.8% of GDP by the end of this year. The Commission’s baseline projection is for it to hit 139% by 2034.

The European Central Bank may not be preparing just yet to unsheathe the transmission protection instrument it announced when it began hiking rates back in July 2022. That was designed to justify emergency buying of Italian government bonds in the event of whatever the ECB decides qualifies as “unwarranted” disorderly market dynamics.

At some stage, however, even France will reach a tipping point where investors lose faith, that is unless inflation does the job of devaluing its debts.

In the short term, the more troubling aspect of this somewhat contained panic in French government bonds is how quickly and how far it has spread risk aversion through other financial markets. It has even hit the new issue business.

The share prices of French banks had (finally) run up strongly this year. So it is tempting to see the 10% declines some have suffered since the election call as profit taking rather than a fundamental reassessment of the credit risk in government bonds held on their books.

But while their share prices sank, credit default swaps spreads on French banks also shot up. And the sell-off spread to stocks in some German and Italian banks, even though these too were still trading on low multiples of earnings and tangible book value.

High rates have been kind to holders of European bank stocks and returns on equity have at last climbed above 10%. But analysts calculate that the sell-off in the last two weeks has brought their cost of equity back above 14%.

It is a worrying sign of vulnerability in the debt capital markets that European bank issuance has suddenly ground to a halt. DCM bankers say we should take comfort that many issuers jumped in early in the year and borrowed heavily and so are not desperate to reprice their curves in a risk-off market. But it’s odd to hear bankers saying in mid-June that we might have to wait until after the summer break in September for a robust primary market.

IPO postponement

And then there is the IPO market. It had revived across Europe this year, giving hope to private equity sponsors that they could sell assets, return money to limited partners and go after new investments.

But then on June 18, one day before Golden Goose, an Italian maker of designer trainers seeking to position itself as a luxury brand, was due to list on the Milan stock exchange, it postponed its offering.

This was set to be a roughly €550 million sale of mostly secondary shares but also €100 million worth of primary shares that would partially deleverage the company.

Bank of America, JPMorgan, Mediobanca and UBS were joint global coordinators. The deal was supposedly covered within the first hour of bookbuilding, in part thanks to Invesco coming in as a cornerstone investor for €100 million. Even though the company says the deal was oversubscribed, it blamed deteriorating market conditions since the European parliamentary elections this month and the calling of an election in France for pulling the deal.

It must have felt like a kick in the teeth for the company’s owner, Permira.

You can blame Emmanuel Macron for killing the golden goose. But when profit taking on French bank stocks spills over into Italian luxury goods and the IPO market, the only conclusion is that financial markets have been much more fragile than we realized.