For years, banks have boasted of their superior “flow internalisation rates” in the battle to be the number-one provider in FX.

Flow internalisation refers to the practice of dealers matching trades through their own internal books, rather than trading on the open market.

|

More transparency is coming. It’s far better to be on the front foot Paul Blank, |

For example, say a bank has Client A who wants to buy $100 million and Client B who wants to sell $100 million – matching them off against each other will save on brokerage costs. If these savings are passed on to the clients, even better.

The key to being the best at internalisation comes down to having enough flow to successfully match off clients, and possessing the best technology.

Naturally, this means the biggest banks that handle the most currency trades – flow monsters – are the best at internalisation, but even second- and third-tier banks like to boast of their capabilities.

Flow monsters have honed their internalisation engines on their trading platforms and aggressively hired the right people. In 2010, UBS wooed Chris Purves away from Barclays Capital – where he built its electronic FX (eFX) platform – to revamp its eFX algorithmic pricing engine.

His efforts resulted in UBS tripling its FX volumes and boosting its market position with those all-important high-volume clients. Purves has been rewarded for his efforts – he is now the global head of macro flow trading within UBS’s FX, rates and credit business.

What’s the catch?

So far, so good. However, times have moved on, and now regulators are probing all corners of FX in the wake of market rigging. The publication of the fair and effective markets review’s (FEMR) final report by the Bank of England last week confirmed what regulators have been grumbling about for some time – internalisation lacks transparency.

The report reads: “The lack of transparency associated with internalisation could limit the ability of clients to assess the quality of execution they receive. Further transparency measures would help to evidence the fairness of the order execution process and the efficiency of the client’s resulting execution.”

Internalisation is starting to lose its shine in some quarters. The FX benchmark scandal has changed the way banks deal with their requests from clients to deal at the fix.

Where you get the problem is when a corporate James Lockyer, ACT |

A senior figure at a multi-dealer platform told Euromoney that not only are banks separating their fix flows from the rest of their flows, some now choose to transact them all externally on multi-dealer platforms. This is more costly, but demonstrates dealers’ attempt to show transparency to their clients.

Internalisation has its shortfalls. According to the FEMR, it can be difficult for clients to assess: how their orders have been handled once received; whether matching methodologies favour particular styles of trading; whether algorithms delivered their promised outcomes; or whether venue rulebooks are faithfully enforced.

Corporates can be vulnerable to opaque pricing, says James Lockyer, development director at the Association of Corporate Treasurers (ACT).

“I think where you get the problem is when a corporate only ever deals with one bank, for whatever reason – it does start to get horribly untransparent how that bank transacts,” he says.

|

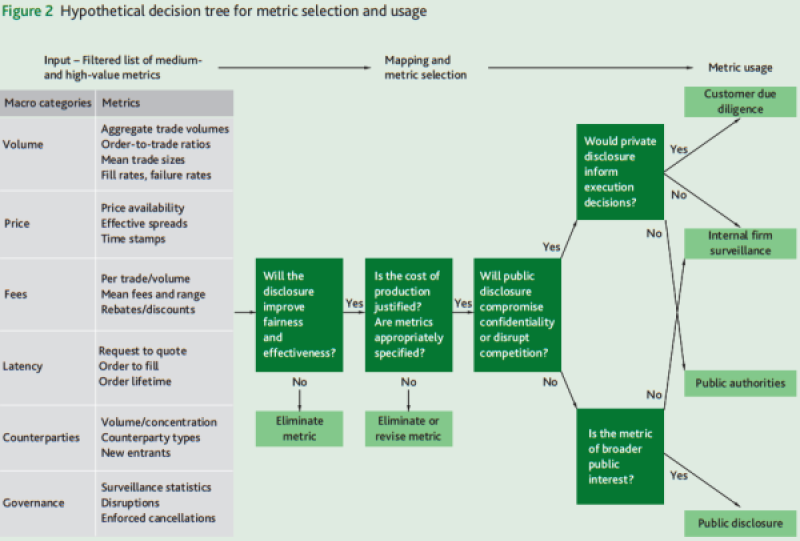

Source: Bank of England |

What’s the solution?

The road to transparency starts with time stamps. Banks could easily provide these to clients, as well as more granular details on how their trades were priced, says Paul Blank, director of e-trading solutions and partner programme manager at Caplin Systems.

This would help clients compare the price they received to the price elsewhere.

“More transparency is coming,” says Blank. “It’s far better to be on the front foot and to pro-actively provide [information] than be dragged kicking and screaming, and be mandated.”

FEMR calls for a market-led initiative to improve transparency in internalisation, by providing “a combination of public and bilateral disclosures”, but acknowledges these will only be effective if adopted across the market, given the global nature of spot FX.

Nevertheless, internalisation is too important to the smooth functioning of FX markets to be readily dismissed. The Bank for International Settlements’ figures from its most recent triennial survey revealed internalisation is “crucial” for large dealers in major pairs, where internal netting was found to be as high as 75% to 85%.

Some banks hit even higher internalisation rates. FX is frequently touted as being the world’s largest, most liquid market – internalisation plays its part in that story.