|

When the renminbi was admitted to the International Monetary Fund’s basket of special drawing rights currencies on the last day of November 2015, joining the euro, dollar, sterling and yen, few were surprised. Beijing had after all pushed to turn the quartet of currencies into a quintet for years, even arguing back in the dark days of 2009 for the renminbi to replace the dollar as the world’s dominant currency unit.

True, the IMF’s assertion that the renminbi had “met the existing criteria” to join the basket raised a few eyebrows. After all, can China’s currency, also called the yuan, really be considered a free and widely used currency beyond the mainland’s borders? Others, alarmed by the turbulence that shook Chinese stocks last summer, and by continued yuan volatility, wondered if the IMF might have jumped the gun. By and large, the long-awaited decision was greeted with calm acceptance.

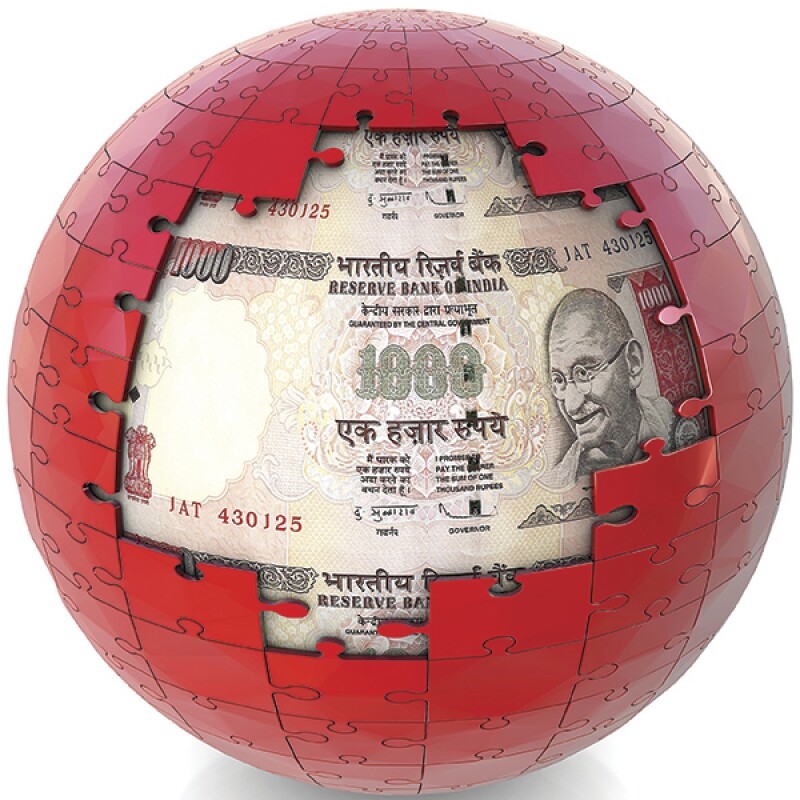

Except in one place. It was only when China began lobbying for the renminbi to join the SDR basket that the “issue of the rupee – what it is, what it stands for, what it wants to become – became a real one”, notes Manoj Rane, head of global markets and treasury India at BNP Paribas.