For so long have senior bankers been telling investors, creditors, rating agencies, customers and anyone else who will listen that they just need interest rates to rise and banks will be much better off, that many of them may even be starting to believe it.

They should be careful what they wish for.

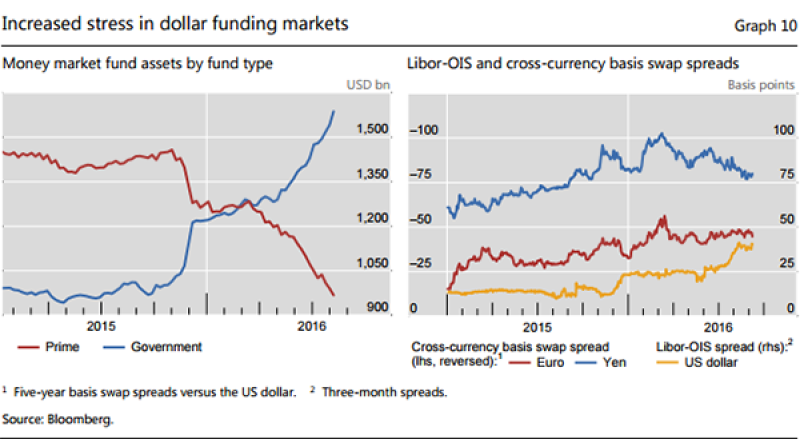

In September, the Bank for International Settlement raised a warning flag for banks over rising Libor rates and the widening spread between Libor and short-term risk-free government bond rates. Libor, for all the scandals around its fixing and despite abundant central bank liquidity injections, still remains a key benchmark of bank short-term funding costs. The Libor-OIS (overnight indexed swap) spread is a closely watched indicator of changing investor perceptions of counterparty credit risk among banks.

Banks want yield curves to steepen and investor perceptions of banks’ riskiness to remain subdued, so that banks can roll over cheap short-term funding and take margin from higher yielding longer-term loans. Central bank intervention and repression of rates across the curve has increased the value of bank assets – a good thing given concerns about NPLs – but has flattened the yield curve and made it much tougher to boost net interest margin.

If the wrong rates now rise and for the wrong reasons, banks may gain no benefit at all, and worse, they might suffer new threats. BBVA research analysts report that the three-month dollar Libor rate increased by 23 basis points between June 27 and September 14 this year. The rise between early July and the start of September of the three-month Libor-OIS spread from 25bp to 40bp looks dramatic, being reminiscent of the global financial crisis.

Consequence

The BIS, and analysts at the more sophisticated institutional investors, all believe that the rise of Libor and the widening of the Libor-OIS spread is the consequence of new rules on US prime money market funds coming into effect in mid-October. Money market funds must now produce floating net asset values based on changes on mark-to-market valuations of their underlying assets, instead of publishing fixed valuations. If truly liquid assets fall below a certain percentage of funds’ overall holdings, then managers must stand ready to charge investors in the funds for withdrawing their cash or even suspend redemptions for up to 10 days.

That’s simply an unacceptable risk for many investors, such as corporations and local governments, that may park short-term balances in money market funds that they need complete freedom and certainty to draw on to make payroll or pay suppliers. As a result, these investors have become much more discerning about which money market funds they place cash in, shifting massively towards those lower yielding funds investing exclusively in high-quality government paper and away from so-called prime money market funds that also invest in banks’ short-term liabilities.

|

Prime funds have been a big source of funding for banks. One year ago they contained about $1.4 trillion. That is down now to around $1 trillion in a shift that has been gathering pace in the run-up to the new regulations coming into force. The BIS says that since June this year some $250 billion has flown out of prime money market funds, much of it switching into government-focused funds. The BIS suggests that this is especially troubling for non-US banks – it points in particular to Japanese banks – funding in dollars and that it has created “incipient funding tensions”.

In BIS speak, that is alarming.

After the US Federal Reserve once again flinched away from raising rates in September, pushing back the prospect of so-called normalization, the last thing that embattled banks need is a curtailment of funding sources and a rise in their own short-term borrowing costs. But that’s what they’ve got. Jeffrey Rosenberg, chief investment strategist for fixed income at BlackRock, suggests that while prime funds may eventually attract funds back with higher yields from buying longer-dated corporate paper, in the next few months assets in prime funds are likely to carry on falling even after the new rules come into effect.

That might push up Libor by another 15bp or more, even if underlying risk free rates don’t move. As the BBVA analysts point out, this is a structural change that affects one of the major sources of short-term funding for the banking system and, far from helping with bank profitability, is yet another threat to it.