|

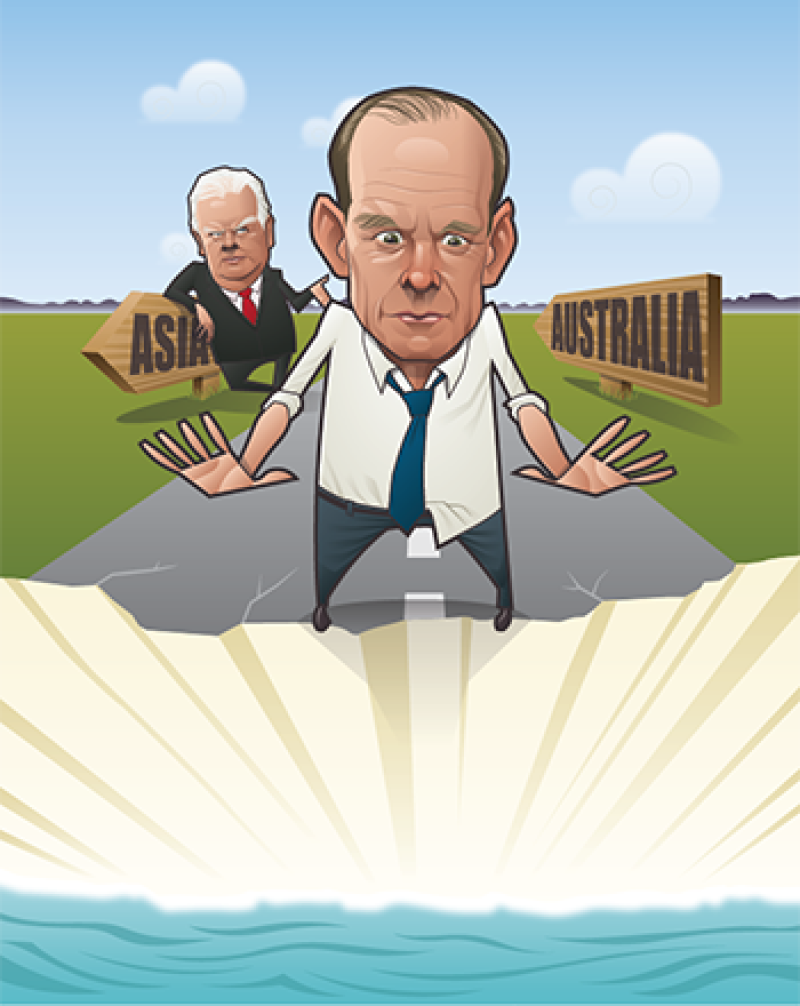

Illustration: Kevin February |

Much has changed since Euromoney’s last visit to the CEO’s office at ANZ. The cast of characters is different; the building itself is different, with ANZ now firmly entrenched in a funky urban campus in Melbourne’s Docklands; and the message about Asia is very different indeed.

Under previous CEO Mike Smith and his Asia-based lieutenant Alex Thursby, a conversation on Asia was an exercise in grand strategy and bombastic promise.

Over a period of years, the target for Asia’s contribution to group earnings, which stood at 7% when Smith joined, got steadily higher, first to 20% and then 30%. Smith spoke of a “super-regional bank”. He spent $550 million on acquiring RBS’s assets in six Asian markets and probably trebled the headcount within four years, peaking around the 10,000 mark by late 2011.

He was still passionately on-message as he handed over the reins to his CFO Shayne Elliott at the bank’s AGM in Adelaide on December 17, devoting at least a third of his address to his Asia vision.

But pretty much as soon as Elliott got started in January, it was clear he viewed things differently. In February he said he would abandon the earnings target for Asia and started talking about slimming the business down.

By the time of his first earnings call, for the first half to March 31, Asia had begun to sound like an embarrassing afterthought, only talked about in negative terms and only asked about by analysts in terms of how quickly he was going to bail out of it. Gone were the grand visions of Asian consumers and manufacturers, of expansion and earnings growth.

So what happened? “Lots of things have changed,” Elliott says.

“If you go back prior to the GFC (global financial crisis), if we sat in a room like this and were talking about a world view, we’d say there’s going to be ongoing globalization, regulatory harmonization, lower barriers to entry and technology will allow you to build scale across a regional platform.”

He talks very quickly, his native New Zealand accent undimmed by years in Victoria, and articulates his points with some energy: “Essentially, the industrial logic would have been: we’ll build a factory in one place, drive volume in these markets through that factory, we’ll get scale that way and the regulators will allow it.”

But it did not work out that way. “What happened in the aftermath of the GFC was that most of those assumptions were wrong,” he says. Barriers went up, not down, increasing compliance costs as they did so. And Asia has underperformed the developed world and most certainly Australia, ever since.

“It doesn’t kill the idea,” he says, “because the idea is a good one, and I can’t really conceive of ANZ not being in Asia because it is core to what we do. But the way we approach it has to change, to move with the times.”

We probably should have invested more in technology, been a bit more thoughtful about some of the target markets we went after. We took on a whole bunch of customers that frankly don’t value what we do for them - Shayne Elliott, ANZ

ANZ has long been a fixture in Asia, with a particular kudos in the more frontier parts of the region. In Vientiane, Laos, it is common to navigate around town with reference to the ANZ building, which, at seven floors, is a relative skyscraper. Its Hanoi branch has been open for 23 years and its bankers have always been among the first journalists call when trying to understand what is going on in Vietnam. Its Cambodia joint venture, ANZ Royal, turned 10 last year. It came as no surprise when ANZ was one of the first western banks to open in Myanmar post-sanctions.

“We have one of the largest footprints in Asia,” says Farhan Faruqui, ANZ’s head of international. “We are present across all of the Greater Mekong, which nobody else is.” And throughout the bank’s long history it has been a successful trade bank, connecting Australia with the region. “Transaction banking is a core part of our DNA.”

|

Smith’s vision was to build on this solid but unspectacular base, peppered with minority stakes in local banks from China to Indonesia, and turn it in to something like Standard Chartered (Thursby’s old shop) or HSBC (Smith’s; Elliott and Faruqui are ex-Citi). It would be a top three bank across the region in a wide range of businesses. It would anchor the bank’s fortunes to the region’s economic growth rates and the banking needs of its young companies and growing middle class. It was a differentiated strategy – no other Australian bank thinks this way, nor ever has – and to implement it, it is thought that Smith became Australia’s highest-paid bank CEO ever, earning A$88 million ($67 million) in eight years.

There is a strong backlash in Australia now against Smith’s track record.

“The only thing Smith excelled at,” says one unimpressed banking analyst, “was getting paid a shit-load of money.”

ANZ’s market value fell 6% under his tenure, it is pointed out, and almost always delivered the weakest return to shareholders of all the big four banks in Australia. And so Elliott is back-tracking on his predecessor’s strategy – one which, as CFO, he was instrumental in developing.

Elliott recalls an internal review at ANZ two years ago when he was CFO and head of strategy in which he was asked: if you could go back in time, would you still do the super-regional strategy? He answered yes, but that he would have done it in a different way, “and I don’t think there’s anything wrong in admitting that”.

How? “Probably a less intense on-the-ground presence; less bricks and mortar, fewer people. We probably should have invested more in technology, been a bit more thoughtful about some of the target markets we went after. We took on a whole bunch of customers that frankly don’t value what we do for them.”

And this is instrumental to what Elliott wants to do about it: “We need to trim back some of those customers.”

Core strengths

Elliott sees ANZ as having two core strengths. One is the retail and commercial bank largely focused on Australia and New Zealand. ANZ is good at this and, better still, has room to grow: its 15% market share of retail/commercial banking in Australia is not much more than half of Commonwealth Bank of Australia’s, and Elliott believes the bank’s technological initiatives will help it get some of that back.

Euromoney’s visit to Melbourne coincides with the first day of Maile Carnegie, hired from Google to be head of digital.

“In five years time, ANZ will be the best bank in Australia and New Zealand for people who want to buy and own a home or to start a new business, and that will be about digital,” says Elliott.

The other side is the institutional bank and it is in this area that Elliott wants to more narrowly focus Asia resources.

“Our institutional bank is all about intermediating trade and capital flow and that’s where the opportunity in Asia is,” he says. “That’s what’s really exciting. That’s what we’ve been doing for 180 years, helping customers move goods and money around the region and the world, and more and more of it is being moved around Asia Pacific.”

|

To handle that business, he says, one needs to be good at trade, debt capital markets, corporate foreign exchange and cash management.

“We are really good at those things. We need to build out that capability across Asia, and it’s time to focus it on those customers that are really willing to pay for it.”

Elliott says that ANZ went from 22nd to fourth in the Greenwich surveys in terms of corporate banking in Asia and that this climb inevitably brought in some of the wrong customers along the way. “What’s a regional bank? It says that I’ve got a capability that is special, that you can’t replicate by cobbling together services from a bunch of domestic banks in the region.”

In practice, he says, that means a business that suits multinationals with needs across multiple jurisdictions.

“The problem is, along the way we acquired a bunch of customers that didn’t want that, who just wanted a domestic banking relationship in Indonesia or Taiwan,” he says.

“And guess what? In the new world, particularly with new capital rules, those customers generally don’t cut the mustard because they want too much of our balance sheet and there’s not enough juice in it for us to generate a decent return to shareholders. So we’ve got to trim them back. We’re going through that at the moment.”

Not only are many customers on the block, it is likely that entire businesses will be too.

|

CEO Shayne Elliott |

Elliott’s more streamlined strategy suggests several units that are unlikely to survive in Asia beyond this slimming of the loan book. One that is widely asked about by analysts is what ANZ calls emerging corporates. This was a strategy about banking the smaller companies that constitute the supply chain for multinationals in Asia.

“The theory was that it was all part of the same value chain,” Elliott says. “The problem with that is that it is a hell of a lot harder to bank those people. It is very difficult to compete with local banks. What’s your edge?”

It also brought credit quality issues.

“We bank that sector in Australia and New Zealand, that’s our bread and butter, it’s what we do all day,” he says. “But we live here, we know them; in Indonesia, we are smaller so it’s harder. It’s a tougher business to get scale in and to understand the risks, so we are scaling it back.” In March the bank said it had closed business lending to SMEs in five Asian countries, cutting about 100 jobs.

One might also expect the private wealth businesses that came from RBS to be sold, particularly given the acquisitive nature of Singaporean private banking arms such as DBS and OCBC’s Bank of Singapore, both of whom look like natural buyers. But that is not quite so straightforward. Those wealth businesses date from ABN Amro’s Van Gogh programme, which was more of a mass-affluent approach than private banking.

“It’s what you might call red-carpet retail, like an HSBC Premier or a Citi Gold,” says Elliott, saying it operates through perhaps a dozen branches in Taiwan, a similar number in Indonesia and a few in Hong Kong and Singapore.

Big enough to sell? He sees it as part of the broader retail operations in Asia Pacific, which are clearly no longer core. “It makes about $700 million to $800 million of revenue, it’s not insignificant. It’s an attractive little business, but not our best, and it’s hard to see what our competitive advantage would be with that.”

A strategic review is underway on it; don’t be surprised if it is sold and if it is, regional headcount will drop considerably.

Asked about the progress of this review in September, Faruqui says: “I don’t want to prejudge the outcome, but doing business in retail outside of your home market, whoever you are, is a tough gig. I know that at Citi, we had a tough time making a profitable retail business in a lot of markets in Asia, and you have seen them shut down in many local markets.”

But Citi does have large-scale and profitable domestic franchises – including retail – in important countries such as Hong Kong, Taiwan and Singapore, something ANZ has never been able to claim.

Retail, Faruqui argues, is “the single most affected business in terms of changes around capital requirements. It is much harder to run in a profitable way today compared with 10 years ago.”

It sounds very much like retail is up for sale, if anyone will buy it. Whoever does will acquire some staff who have gone from ABN Amro to RBS to ANZ to the new buyer in the space of a decade without ever changing desks.

One area that is unarguably up for grabs is ANZ’s scattered collection of minority stakes in Asian banks. There are several: a 38.9% stake in PaninBank in Indonesia; 24% of AmBank in Malaysia; 20% of Shanghai Rural Commercial Bank; and about 12% of Bank of Tianjin. Some of them date back to the 1990s; all of them are surplus to requirements.

“The logic at the time was: here was a relatively low-cost, low-risk way of having exposure to Asia,” Elliott says. “It was a way to learn about those markets, to give shareholders some exposure, and they each had a path to control at some point in the future, should you choose to go down that path.”

This, too, has changed.

“The GFC flipped that up,” he says. “I don’t know that there is a path to control on any of them now.”

And so holding them no longer makes much sense. “My logic is simple. I say: none of our shareholders buy stock in ANZ to get exposure to them and none of our customers give us business because of any benefit they get from the relationship. They don’t have a strategic value. They have a financial value – they have actually generated really good returns for shareholders – but they are chewing up about $5 billion of our capital, and that’s not insignificant.”

Eight years ago there were 10 people in the dealing room in Singapore. Now it’s our biggest single dealing room anywhere. Our institutional markets franchise is truly global and truly competitive - Farhan Faruqui, ANZ

In fact it is about 10% of group capital, which makes even less sense since capital rules in Australia have changed, doubling the effective cost of holding these stakes.

Selling out of them is an easy decision – even gung-ho Smith sold out of two similar minority stakes in Vietnam – but may be easier said than done. It is true that the Bank of Tianjin stake has fallen from 20% to about 12%, but that did not involve a sale, or any income to ANZ; it just means ANZ did not participate in a couple of Bank of Tianjin capital raisings and so got diluted.

Nevertheless, Elliott insists there is interest in all of them, whether from domestic institutions, international funds or private equity. He will not make a prediction on timing – “I’m sick of that” – but does say there are challenges involved in completing a sale.

“One, they’re quite big: they are not things you could sell on-market. And each is complex in its own way. Some are partnerships, so any agreement has to be with the partner’s approval, which makes it a three-way conversation,” further complicated when a key family member at Panin died, for example. “And clearly there are lots of political or regulatory sensitivities around who owns the stakes.”

On top of that, buying minority stakes is not particularly fashionable these days. Asked about potential buyers for the ANZ stakes, one leading M&A banker in the region comes up with just three potential groups – Japanese banks, Taiwanese banks and international private equity.

There are other reasons it would be useful for ANZ to divest these stakes. AmBank is involved in the 1MDB scandal, since it is the bank where the disputed accounts belonging to Malaysia’s prime minister Najib Razak are held and through which hundreds of millions of dollars of trades took place that are now under investigation by the US Department of Justice, among others.

ANZ holds board seats at AmBank, one of them occupied by Graham Hodges, the ANZ executive tasked with the minority sales; several of ANZ’s staff have been seconded into AmBank over the years. Surely it is a reputational risk?

“Well, that doesn’t help,” Elliott says. “But putting AmBank aside specifically, it is true that you may own 10%, 20%, 30% of an economic interest in something but you’re on the hook for 100% of the reputational risk. Nobody remembers if you own 5% or 50% if your name’s there.” ANZ has already written down the value of its holding in AmBank.

Pinning down Elliott or Faruqui to any kind of target for Asia, whether in terms of earnings, headcount or position, is problematic since the business is no longer structured in a way that separates Asia from anywhere else. We can see that Asia Retail & Pacific accounted for just 2% of group profit in the first half and that international overall accounted for 9% (that is, barely one third as much as New Zealand), but we cannot break down Asia’s contribution to the institutional division.

“We get asked a lot about our business in Asia,” says Elliott. “I say: we don’t have a business in Asia, we have a business across the whole region including Australia. We have people and customers there, but I don’t think about how many there are just like I don’t think about how many people we have in Queensland.

“If we sat down and allocated our profits so that I could figure out exactly what’s in Asia, I don’t really care if that’s 25% or 35% or 12%, to be honest. That’s not the right way to think about it.” The reporting structures at ANZ now tend to be less geographical than split between retail/commercial and institutional, regardless of location.

Widespread worry

While Elliott can make a good case for a slimmer Asian business to an Australian investor and analyst base, the view on the ground in Asia is rather different. Insiders contacted by Euromoney speak of an atmosphere of uncertainty and lack of direction, with widespread worry about which businesses will be retained, which cut back and which sold.

The departure of Andrew Géczy, head of international and institutional lending, at the end of January was seen as portentous. The departure of Debra Tay and a number of her wealth management colleagues in February this year, who joined Credit Suisse’s better offering for private banking clients, alarmed the rest of the office. The departure of Joseph Abraham, head of the Indonesia office, combined with the planned sale of the Panin stake, suggests a lack of commitment to one of the few Asian markets that appears to be delivering right now.

Perhaps the most important departure was Carole Berndt, the head of global transaction banking based in Hong Kong, a veteran of RBS, Bank of America Merrill Lynch, Citi and American Express, among others. As such, she was front and centre of the rationale of ANZ’s international business – in Elliott’s own words: “Helping customers move goods and money around the region.” Her departure in June was unexpected – the more so since, Euromoney understands, she did not resign but was removed.

One former ANZ executive tells Euromoney: “I do believe that what they attempted to do, and what Shayne is now trying to refine, is a good strategy.”

But it wasn’t easy. “When you get under the covers, some of the complexity of being an international bank really starts to emerge – and that applies to most banks,” the former executive says. “Taking your existing processes, systems and culture and putting them into different geographies and expecting them to be a meaningful and sustainable in a short period of time – everybody thinks they can do it, but it’s not that easy. All the pieces of the jigsaw were there, but putting the picture together has proved challenging.”

In the market, there is confusion. Competitors see a bank that waded in, spent big, committed a lot of capital, then apparently gave up as soon as the going got tough and with a huge amount already invested in the infrastructure.

Few in debt capital markets see ANZ as relevant.

“They lent loads to potential capital markets clients when they made the push, didn’t convert them to capital market deals as they don’t have a distribution network and have basically given up now,” is a typical response from one of the big investment bank competitors. A leading headhunter adds: “They built up too many expenses and too much risk, and then Asia stalled.”

Is this fair?

|

Farhan Faruqui, ANZ’s head of international |

Faruqui insists that the markets business, which has been built from scratch over seven or eight mostly Thursby-less years, is thriving, and accounts for a third of Asian revenue. He claims that in both loan syndication and DCM the bank is ranked third in the region ex-Japan – although, crucially, he includes Australia in that picture (since the link between Australia and Asia is instrumental to ANZ’s strategy).

“Eight years ago there were 10 people in the dealing room in Singapore,” he says. “Now it’s our biggest single dealing room anywhere,” with over 100 staff covering commodities, FX and rates among other things, and taking advantage of a comprehensive range of local currency licences. “Our institutional markets franchise is truly global and truly competitive,” he says.

In the transaction banking business, alongside the long-standing excellence in trade finance, cash management has been a priority.

“That is going to be a big source of our growth,” says Faruqui. “It is a great business to be in, a huge boon to the overall ability to grow with a client. It’s the most accretive business from a return-on-equity perspective.”

He insists that “the balance sheet remains substantial and we will make sure we leverage it,” although everything Elliott has told analysts suggests that the commitment of capital in the region will be reined in.

The problem is that independent numbers contradict Faruqui’s claims.

In Asia, DCM volumes ex-Australia and ex-Japan, year-to-date numbers provided by Dealogic show ANZ as not top three, or top 10, but 57th. On DCM revenue, it ranks 58th. ANZ, in turn, says it was on every DCM deal from China Banking Regulatory Commission-regulated financial leasing companies this year.

The bank also points to standout deals including a $2 billion RegS from Huawei, the largest-ever unrated dollar RegS bond globally; a $1.75 billion dual-tranche deal from Kexim, which was in November so does not appear in our ranking; and a tier-2 $700 million bond from UOB.

|

Then there is transaction services. In Euromoney’s annual cash management survey, published this month, based on 15,000 votes from clients in Asia, ANZ declines in almost every segment; falling from 23rd to 35th among non-financial institutions globally year on year; and from 12th to 24th in Asia.

The picture at a country level is more disappointing still, even in the more frontier markets where ANZ has traditionally excelled. In Hong Kong, the bank slips from 10th to 27th for corporates; in Indonesia from fourth to 18th; in Taiwan from fifth to 12th; and in Vietnam, from second to 10th place.

|

The annual industry benchmark Euromoney foreign exchange survey for 2016 (published in June) tells a similar story. In all products for Asia ANZ has dropped from 16th to 27th between 2014 and 2016, and from 20th to 30th globally. Among banking clients in Asia, it has gone from 12th to 30th and among non-financial corporations in Asia, from 12th to 21st.

And if Asian cash management is to be a mainstay of the ANZ business, why is Berndt’s replacement, Mark Evans, based in Sydney?

ANZ group executive for institutional, Mark Whelan, recently spoke of rationalizing the client base back to the 6,000 clients it thinks it has a viable business with. The problem is, those are the same 6,000 clients every other bank wants.

“Given that we are in an age of disruption and uncertainty, if you’re a corporate, is this when you’re going to make a material shift in strategy around your banking partner?” asks the former executive. “Or are you going to the safety of Citi and HSBC? Nobody gets sacked for banking with them. You can say to a corporate: you need to make my capital pay, and I want your DCM and FX, but that’s not enough of a reason for them to want to make that shift.”

These are, of course, industry trends rather than specific to ANZ, and some think the bank will achieve the right outcome.

“I wouldn’t limit it to ANZ, many organizations are trying to streamline strategy in Asia,” says a leading regional headhunter. He adds that he is not seeing many people coming on to the market from ANZ and that when he approaches people at the bank to move – typically in sophisticated financing – they are still reluctant to leave. “Longevity of franchise is the name of the game in Asia these days, rather than being everything to everyone.

“‘Retreat’ is just a headline; the story in Asia is realignment,” he says. “ANZ’s policy looks very logical to me.”

But that only works if ANZ starts moving forwards, not backwards, in the businesses it now says are priorities.

And even if one accepts the view that a more streamlined business in Asia might be a better way to go, the question remains: why build it, at such expense, at all? As Jonathan Mott, banking analyst at UBS in Sydney, asks: “Why was such low-returning Asian institutional business written in the first place?”

The whole RBS acquisition looks like a mistake now. And Elliott, now presented as a new broom, was part of the expansion.

Some have a problem with the idea of someone who was involved in the build-up being the one entrusted to shrink it.

“The problem is, he is an insider, he was complicit in the build-up of it,” another analyst says. “I like Shayne, he’s a nice enough guy, but is he genuinely the best you could get? ANZ shareholders have had the shit kicked out of them for eight years. They deserve the best, and that’s not someone who was involved in making the mess in the first place.”

Home-grown

Still, whatever Asia looks like, it is clear that the Australian analyst community – and by extension, investors – wants it to be smaller. This is nothing new. With the possible exception of the insurance group QBE, it is hard to think of an Australian financial services business that has ventured overseas without instantly triggering a revolt by shareholders.

NAB’s adventures in the UK have been largely disastrous, hence the renewed popularity of CEO Andrew Thorburn for shedding assets like Clydesdale. Investors generally like their Australian banks to be as simple and home-grown as possible.

In May UBS’s Mott, one of the most closely followed names in the industry, said he expected ANZ to run off a net A$30 billion of low-yielding risk-weighted assets by fiscal 2018, particularly from Asia and as much as A$60 billion if product spreads in Asia do not improve. “The returns ANZ has generated from the Asian region have been poor,” he says now, and they would be improved by exiting.

Mott says Elliott “is making the right strategic decisions” but should, if anything, hurry up, even if it means swallowing some grim prices for its minority positions.

“ANZ may need to be less price-sensitive with the disposals of its Asian partnerships,” he says. “The market already ascribes limited value to these positions, and any capital release on disposal is likely to be well received.”

Elsewhere, JPMorgan analyst Steve Manning upgraded ANZ to a buy based partly on Elliott’s “decisive action” on redeploying capital away from Asia.

In Australia, Elliott is applauded for a retreat that baffles some in Asia and is criticized for not doing it faster.

“In the last half, he made a $717 million write-off,” says Brian Johnson, analyst at CLSA, another of the industry’s most influential voices. “If I was in his shoes, I would have gone a lot, lot bigger. Without particularly trying I can find about $2.7 billion in write-offs.” Asked to break that down, he mentions the capitalized value of software, the value of the Asia partnerships, corporate lending and stranded costs as the business shrinks down.

|

The stay-close-to-home mentality used to drive Smith to distraction and he would frequently complain that the market was failing to understand his vision. Even at his AGM farewell speech, he spoke about having to “swim against the current” with his super-regional strategy. Elliott argues that the stay-home view is not universal: “There’s some that think like that, not all. But there is a view out there among some fund managers and analysts that they would prefer the banks were purely domestically focused.”

He continues: “The logic is not unsound. Assuming history is a good guide – which we all know it isn’t – the best place you could have put a dollar into any financial services business in the world over the last 20 years is Australian, and perhaps Canadian, domestic banking. High return, growing markets, relatively low risk, low volatility; all the things that shareholders love.

"So when you come along and say: ‘Hang on, we want to do something different’, of course they raise lots of questions.”

Chief among them being: how are you going to create any value? Not an unreasonable view when you are used to Australian returns. ROE in Australian retail has consistently hovered around 17% to 18%. The country has not had a recession for 24 years. It has been extremely fortunate.

“So there is a view that if Asian banking is 7% or 8% ROE, why on earth would you take money from Australia and put it in Asia? Well, they’re quite right, that would be foolish, but we’re not doing that,” says Elliott.

Instead, he argues, ANZ is putting as much money as it usefully can into Australia and New Zealand – and in fact has grown market share in Australia for six consecutive years – but has a chunk of organic capital left over that it can either give back as dividends or invest elsewhere. Moreover, he says, if the right businesses are chosen in Asia, around intermediating capital flows, those returns get up towards 13%.

Elliott will get a honeymoon period as CEO and can weather the negative press if he delivers better shareholder returns. And, he insists, Asia has a big role to play in that.

“The institutional bank – around Asia in particular – is going to be a far more focused, streamlined business around trade and capital flow,” he says. “We want to be the best bank in the world for customers who move goods and money around Asia.”

This story was corrected on October 31 to accurately reflect the terms of Debra Tay’s departure from ANZ. We apologise for the original error.