The UK’s Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) first announced plans for a safe space in which financial products could be tested outside of regulatory constraints at the launch of Project Innovate in 2014. The aim was to promote innovation and help emerging fintech companies aiming to disrupt the discredited incumbent banks to navigate the strict regulatory landscape.

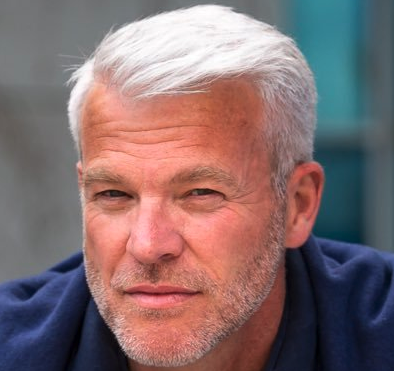

Jerry Norton, vice-president, financial services, at banking services provider CGI, says: “The sandbox concept arose from the

|

|

|

Jerry Norton, CGI |

confluence of the post-crash clamour for more regulation with the initiative in the UK for more fintech.”

The first group of participants, known as cohort one, comprised 24 institutions, drawn from 69 applications. The FCA is now holding applications for the second cohort open until January 2017.

Overall, the industry is highly supportive of the regulator for taking the initiative to support fintech development. “The sandbox gives the regulators forward visibility on what is developing, and gives them influence on the creation of the product while it is still being produced. It is exactly what a proactive regulator should be doing,” says Norton.

EY’s UK Fintech: On the Cutting Edge report notes that the creation of the sandbox is particularly innovative and progressive for a national financial regulator, creating a template that other countries have been quick to replicate.

Norton says: “The decision of the FCA to establish the sandbox is a huge benefit to the UK financial services market – providers and technology companies alike. Other bodies that have been suggested cannot be as effective as they are not in control of financial conduct. It has to be the regulator or the central bank that runs the sandbox or it will not benefit all.”

Independent industry consultant Tim Lund says: “The FCA is leading the way, and we are seeing Australia, German, France, Hong Kong and Singapore now all following.”

In other regions there are different approaches to what is required from the sandboxes depending on their individual market focus.

|

|

Imran Gulamhuseinwala, |

Imran Gulamhuseinwala, partner, global fintech leader, EY, says: “The Singapore and Hong Kong sandboxes have different approaches. The Hong Kong sandbox is looking to serve its home market of China, whereas Singapore is facing outwards to southeast Asia. Both sandboxes will follow their own regulations but clearly cannot speak for the regulators in other markets.”

The FCA’s structure further pushes the aim of turning the UK into a hub for fintech innovation. Gulamhuseinwala says: “The UK has an open sandbox, making it available to not just fintechs and large banks but also non-financial services players. The ambition is for the UK to become a domicile for innovative financial services players to validate their business models.”

Lund adds: “It is encouraging innovation. It is making London a competitive place to operate and potentially attracting jobs and commerce to the market.”

The FCA clearly outlines the requirements for companies to enter the sandbox, calling for products that are tackling a previously unaddressed issue, and have specific benefits to the UK market.

Its stance pushes the concept that innovation is approved of, and gives financial services the option of testing out innovations that have so far been regarded with caution, such as blockchain and the cloud. Norton says: “The FCA is leading by example. If it is seen to be doing things outside of the box, that encourages the rest of the sector to follow suit. It is critical the regulators are seen in a different light, as progressive.”

Although such a proactive stance has drawn praise, there needs to be caution that the products developed within the sandbox are not given an unfair advantage in an industry carefully navigating through regulation.

“What can’t happen here is the creation of an unfair playing field for those who don’t have the oversight of a banking franchise,” says Lund. “It is not the regulator’s role to determine the winners and losers; the process has to be transparent. The regulators have to be very careful of avoiding anything that looks like an endorsement.”

Lund emphasizes that the process is supposed to be a place for development, and should not be allowed to become a kite mark of regulatory approval. “Being through the FCA sandbox cannot be allowed to become a marketing line,” he says. “It is starting with that, and there have been some instances of successful participation within the sandbox being mentioned. The technology developed should be the differentiator, not the status with the regulator.”

Further, it needs to be recognized that if any product has not been accepted it might be because it has not reached a level of maturity, rather than because the concept is a regulatory non-starter. CGI’s Norton says: “If a company’s product is not accepted it will likely indicate it is not at the point of testing, or it is not radically different enough to be accepted. It is not intended, but there is the possibility of a stigma being attached to not getting into the sandbox.”

With the sandbox, the FCA has taken an important step towards making the development of regulation more of a two-way process. But there are other areas that might benefit from this greater level of open dialogue. Lund suggests it is time to look at what other areas are causing concern within the industry and work directly with participants towards a solution, especially when there is room for confusion.

“The regulators need to be looking into how they can add value,” says Lund. “They can close the gap between intention and interpretation. They can reduce legal uncertainty and protect investors at the same time. They can also address the issues created by innovation, like cyber security, fraud, and data privacy concerns. You can foster innovation and still manage risk. It doesn’t mean you waive the need for a banking licence or the compliance principles a bank must follow, especially if you are effecting transfer of value or capital formation.”