Credit Suisse is now two and a half years into a three-year restructuring instigated by chief executive Tidjane Thiam. The board appointed Thiam in March 2015 to succeed Brady Dougan, the veteran derivatives trader who had first joined Credit Suisse Financial Products 25 years earlier in 1990 and risen to head the group in 2007.

| In this story |

| • Surrounded by doubters: from Prudential to Credit Suisse |

| • Shock and awe: cutting trading, serving the private bank |

| • The richest of the rich: a new approach to UHNW clients |

| • The necessary outsider: what Thiam could see, and what scared him |

| • The IPO that wasn't: how to buy time and influence people |

| • 'Something went wrong': an early setback from trading losses |

| • Standing up to bankers: lessons from Côte d'Ivoire |

| • 'There is no plan B': Thiam and the DoJ RMBS settlement |

| • Pulling together: how structure has helped Thiam's vision |

| plus |

| • Running for the IPO that never came |

| • Lessons from a turnaround |

Taking over from a legendary figure at the firm at a troubled moment in its history, Thiam studied the earnings profile, growth potential, embedded risks and running costs of each of the bank’s core businesses, as well as the group capital position and reporting structure.

He decided radical change was essential in every single component.

Chief executives are normally at their most powerful during their first months in charge, especially when they are outsiders brought in by boards of directors to enact change. But Thiam was surrounded by doubters outside and inside the bank.

He was an experienced chief executive, arriving from the top position he had held at Prudential from 2009 to 2015, having previously been chief financial officer there and before that chief executive for Europe at Aviva. But the old snobbery of bankers towards insurance counted against him. Banking is a complicated business, not something that non-bankers should rush to try.

“I don’t want to underestimate the complexity of banking, but I’m hardly a stranger to financial services or to financial markets,” Thiam tells Euromoney. “We all deal with the same yield curve, the same equity markets, the same volatility. Yet people were acting as if I had landed at the bank from planet Mars. Saying that it was risky for Credit Suisse to appoint a non-banker felt to me like a cheap shot.”

It was in recognition of this passionate, intellectual and driven chief executive’s bold overhaul of Credit Suisse – the results of which are only now becoming evident – that Euromoney recognized Tidjane Thiam as our banker of the year for 2018.

This is not a man who ducks a fight.

At Prudential, he was criticized for pursuing the large acquisition of AIA very early in his tenure as chief executive when he sought to reposition the UK-headquartered insurer for Asian growth. Investors grumbled about what they saw as the high cost of that deal. It slipped away and with it their chance to enjoy the enormous value creation that duly followed when AIG instead floated the business.

Thiam had urged investors to support a bid of $35 billion for AIA but, new to the role, he couldn’t carry them. Three years after AIG floated it to its delighted new stockholders the target was worth $60 billion and is now valued at over $100 billion.

Thiam’s judgement had been right and, a sometimes prickly character, he takes occasion to remind people.

“I have always preferred to pursue organic growth over M&A. But that just tells you how big the opportunity was with AIA,” says Thiam. “However, there are certain historic capital allocation similarities between the businesses at Prudential and Credit Suisse. At Prudential, the UK business was 50% of the profits when I took over as chief executive and it expected to receive unlimited new capital, which it was investing for a 9% return.”

That doesn’t sound too bad, but Thiam explains: “It was starving Asia, where we could make 40%-plus returns. I realized that the home market can sometimes be a drag on capital allocation in an international group.”

No one enjoys being made to look a fool. Being right about AIA made him a number of enemies, gave a hint of controversy to his personal brand and left him with something to prove.

Shock and awe

His restructuring plan for Credit Suisse, mapped out before he took up the reins in July 2015, was revealed in October of that year and launched at the start of 2016. It began with shock and awe as Thiam recast a bank that had come to be dominated by its markets trading businesses into one that would be dominated by its private banking and wealth management operations instead.

Roles were reversed. The super smart traders would no longer be the masters of Credit Suisse. Rather, those that kept their jobs would now mainly serve the private bank that many traders had looked down on as the sleepier side of the business.

Thiam was lucky, of course, that Credit Suisse had such a strong private bank to fall back on. Without it, Credit Suisse could easily have suffered the same fate as Deutsche Bank, another firm run by former derivatives traders that had appeared to come through the crisis better than peers and without requiring a government bailout but had then foundered.

“This is a fabulous bank,” Thiam tells Euromoney. “Or let me be more precise: it has always had a fabulous bank within it. Our wealth management franchise and some of our top investment banking franchises were always there. It’s just that the bank had not been managed to leverage all our capabilities and maximize our potential, particularly in wealth management.”

Perhaps doubters were looking at the old vision of private banks that had assisted in tax avoidance and sold on secrecy rather than investment performance; or at some of the disreputable brokers in the US and UK that would sell anything for a commission and had damaged the value of their companies’ brands.

What Tidjane Thiam has brought is a very clear strategic focus. It’s very important for a bank to know what its true purpose is. But many banks don’t

Thiam had different ideas for what an up-to-date wealth manager could be.

Having the raw building blocks was, however, about as far as his luck went. Restructuring is painful. The bank reported a loss for 2015, Thiam’s first year as chief executive, when acceptable core operating results were overshadowed by big hits taken on toxic positions lurking in the Global Markets (GM) trading book and other non-strategic and problem assets now transferred into an internal bad bank, the strategic resolution unit (SRU).

The losses continued in 2016 when Credit Suisse settled with the US Department of Justice (DoJ) over residential mortgage-backed securities (RMBS) and the red ink continued to flow in the SRU.

For 2017, the bank did manage to report full-year pre-tax income of SFr1.8 billion ($1.81 billion), roughly what it made in the first quarter of 2015, Dougan’s last before Thiam took over. Sadly for Credit Suisse shareholders, however, US tax reform passed at the end of 2017 promptly translated this into an attributable net loss for the year of SFr983 million.

In the first quarter of 2018, progress was beginning to look a little clearer. The first three months of 2018 marked the highest group profit in 11 quarters and the sixth consecutive quarter of year-on-year profit growth. Pre-tax income came in at SFr1.2 billion, at least back within sight of, if still 25% below, the SFr1.6 billion reported on Thiam’s first earnings call as chief executive, the second of 2015.

The richest of the rich

Customers seem to like what the bank is becoming: a wealth manager with a particular focus on ultra-high net-worth (UHNW) clients, the very richest of the rich and often entrepreneurs and owners of private companies with substantial business banking needs of their own.

Credit Suisse covers these very wealthy individuals in much the same way that top investment banks have traditionally covered the CFOs and chief executives of multinational corporations. There are personal visits from top executives who will act on customers’ behalf and the provision of sophisticated investment banking, lending and structured investment services. It aims to be for them what Goldman Sachs once was for Ford in the glory years of Wall Street.

|

The bank pulled in SFr14.4 billion of net new assets in the first quarter of 2018, mostly from Asia and other emerging markets. That compares with SFr4.7 billion in the first quarter of 2015. Back then, Credit Suisse calculates that it saw a roughly 25% share of net new asset flows from UHNW clients. Fast forward three years and it reckons it now has a roughly 70% share of this key client segment.

“What Tidjane Thiam has brought is a very clear strategic focus,” says David Mathers, chief financial officer. “It’s very important for a bank to know what its true purpose is. But many banks don’t, other than that they have been around for 100 years. Beyond being part of the establishment, what do they want to do for clients? There’s a lot of fuzzy thinking around products and customers.

“Credit Suisse sees a phenomenal opportunity for a private bank particularly focused on UHNW clients, many still working with their shirtsleeves rolled up on their businesses, that want lending and liquidity as well as investment products. That client base has always been underserved.”

It may come as a surprise to some, but it turns out that Thiam, the former McKinsey consultant, the arch strategist, is a pretty good client guy. Euromoney meets him in London in December, where he has spent the previous day taking one of the bank’s UHNW clients from Asia around the offices in Canary Wharf meeting traders and bankers.

The client has apparently enjoyed the trip, the kind that investment bankers used to invite chief executives of large public companies on. He emails his thanks and drops, almost as an afterthought, that he will be sending Credit Suisse another SFr200 million to manage.

At a second meeting in Zurich this June, Thiam has come from dealing with a UHNW client alarmed to find a bidder preparing an unwelcome offer for one of his companies, apparently supported by financing commitments from Credit Suisse. Thiam has jumped in to sort this out. Another part of the bank reckoned the deal could earn Credit Suisse substantial fees. But it will not do this now.

“I explained to them,” says Thiam, choosing his words carefully, “that the client’s trust in us is worth more than the fees we may lose in the short term.” The client sends his thanks that the chief executive has seen to this personally and has decided to increase his assets at Credit Suisse, which already amounted to billions of dollars.

Shareholders are slowly coming around to the idea of a bank reducing its dependence on volatile trading businesses that may not be so profitable even in the good years in future. Trading businesses will be lucky to see 2% compound annual growth rates in volume and the rise of the algorithms will hammer margins. Wealth management is at least a growth business. The Credit Suisse share price hit its low in July 2016 at just under SFr10 and stood at SFr15 at the start of July this year.

The necessary outsider

Is this sufficient cause for celebration? And is it now clear that it needed an outsider to come in and save Credit Suisse?

“Well that’s clearly what the board thought,” says one departed senior executive who may once have harboured ambitions and still holds a grudge.

It is a telling comment, revealing the enmity that Thiam encountered from certain insiders and, perhaps more troubling, the extent of the delusion that they had been leading the bank along the right path.

Credit Suisse had come through the financial crisis better than most, running down risk-weighted assets earlier than its rivals. But it had then lost its way, perhaps believing too much in its own trading prowess and doubling down in markets businesses. These came to dominate group RWAs and earnings, outstripping the combined contribution of its Swiss universal bank, wealth management and asset management divisions and advisory and banking and capital markets businesses.

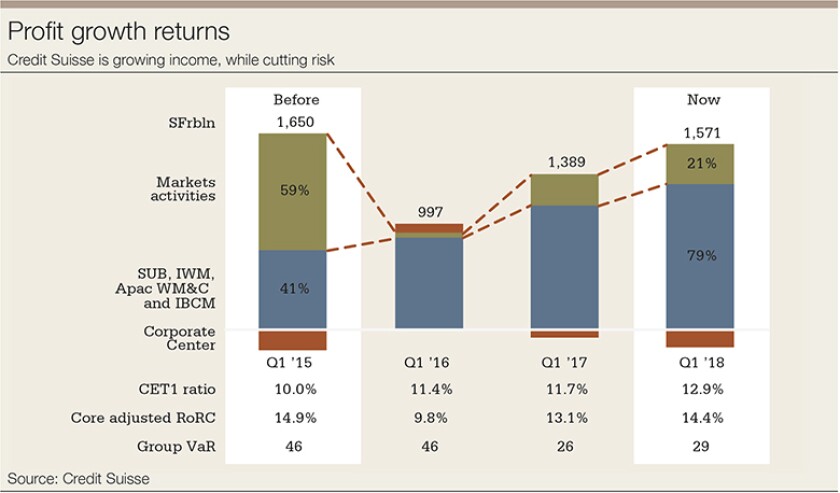

In the first quarter of 2015, global markets contributed 59% of core adjusted group profits at Credit Suisse.

Thiam saw what some insiders could not or did not want to. The bank had taken on too much risk. It had placed most of its chips on markets businesses that were subject both to low volume growth and margin compression and whose returns were volatile. Costs were far too high. Even more worryingly, the bank still needed to settle with regulators for the sins of the past.

David Mathers, Credit Suisse's chief financial officer

Its leaders had repeatedly told investors that Credit Suisse did not need more capital – another echo of Deutsche, whose executives used to bemoan investors and analysts who could not accept that the swollen balance sheet was mainly high-quality risk and well hedged.

In fact, raising capital was essential for Credit Suisse. So was reworking the business model. Thiam came in and announced that all this must change. It was a distinctly unpopular message to some.

What those inside the bank absorbing what it meant for them personally in 2015 may not have realized was how lucky Credit Suisse had been to land its revolutionary leader. It had taken a long time and a lot of effort to persuade Thiam to join.

“The chairman [Urs Rohner] tells me we had 19 meetings,” says Thiam. “I had told him I would consider the position only if he talked just to me about it, because I was taking a risk in talking to him at all. And then the more I looked at it, the more challenges appeared. It would be tough to address lack of growth, too much risk, costs being too high, lack of capital and very significant legacy issues each on their own. But to deal with all of them in parallel looked like too much. I actually said no twice.”

The insurance part of my brain was very used to thinking about contingent liabilities. I now realized that what we needed was a contingent asset

But the truth is Thiam likes a challenge. Of course, he knew he wouldn’t be welcomed with open arms.

“In business, you might be short-term popular or long-term popular but rarely both,” he says. “Bankers are paid for taking risk. If you cut their risk budgets, you cut their pay.”

But he kept talking and eventually, perhaps feeling an obligation to a persistent suitor, after almost a year, he decided.

“I had more detailed discussions over my concerns. I remember one call through most of a night with Dick [Richard] Thornburgh [a veteran former FIG banker, CFO and board member of Credit Suisse] and I eventually said: ‘I think I know how to do this, but I can only do it if I have the total support of the board.’”

And what, Euromoney wonders, was it then like when he joined the bank in 2015 and finally got to look under the hood as an insider?

“I couldn’t sleep,” Thiam says. “July 2015 may have been one of the worst months of my life.”

Thiam had been fully prepared for internal opposition to his plan to rein in the bank’s traders. However, this was not rocket science, rather an obvious and overdue strategic shift, driven by the higher RWA density of market risk businesses under post-crisis regulation. It was one that shareholders should welcome as a run-down of a high capital velocity and volatile business, combined with the build-up of slower but steadier ones with more growth potential.

But he also knew that to achieve it one of his first tasks would be to dilute shareholders.

“I am very shareholder focused,” Thiam says. “I understand the importance of capital in financial services. I believe that the best source of capital is organic generation from profitable growth and that going externally to raise it is only ever the result of failure and is no way to run a business. But to give the company a successful future, I first had to dilute its shareholders.”

|

For the second quarter of 2015, Credit Suisse had reported a 10.3% common equity tier-1 capital ratio, below that even of challenged peers such as Barclays and Deutsche and far below UBS. Perhaps worse, its CET1 leverage ratio stood at just 2.7%. The bank needed to act.

“I had said I would not take the job without support for the plan to raise capital,” Thiam says. “I had thought we might need to raise SFr4 billion to SFr6 billion but, subsequently, I became convinced that we would ultimately need to raise SFr10 billion, maybe more, to have the kind of balance sheet strength I deemed necessary to our success. That was a sobering realization.

“It wasn’t just the looming settlement with the DoJ on RMBS. There were numerous other lawsuits as well as balance sheet issues, including with some long-term derivatives positions.”

The IPO that wasn't

Plenty of battles still lay ahead for Thiam but in October 2015, as part of the restructuring plan, he pulled what may have been the most audacious head fake of a move, announcing the partial IPO of a substantial stake, perhaps 20% to 30%, of the Swiss universal bank to be completed in the second half 2017.

There was some talk of releasing value and a way to participate in domestic consolidation, but this always sounded like flimflam – the cover story for an almost desperate move, one that would sell down a stake in one of the more stable, large business units.

For the whole of 2015, with the bank now reporting in six new units, the Swiss universal bank, combining onshore wealth management, domestic retail and corporate and investment banking, brought in SFr1.6 billion of adjusted pre-tax income. That was more than the new Asia Pacific unit, which brought in SFr1.1 billion from a mix of wealth management and corporate and investment banking in Asia; global markets, which also made SFr1.1 billion of pre-tax profit; and international wealth management (IWM), which reported SFr1 billion, mainly from emerging markets.

Investment banking and capital markets (IBCM), now separate from global markets, brought in nothing from advisory and financing, while the corporate centre and the SRU lost money – and lots of it.

The return on regulated capital wasn’t great at the Swiss universal bank, coming in at just 13%, compared with 24% for the smaller IWM division and 16% for Apac. But the normal motive to partially IPO a division is to draw attention to the value of a high-growth part of the company in an effort to rerate the sum of the parts. Analysts were left scratching their heads that Thiam should have so quickly become so desperate for capital that he was going to sell down a stake in the core earnings.

If investors wanted a steady and stable return play on onshore private banking, Swiss retail and Swiss corporate and investment banking, then sure they might well invest in the new universal bank equity. But presumably many would ditch their Credit Suisse stock as a much more uncertain growth play on emerging market wealth, now with less ownership of more dependable earnings.

Yes, Credit Suisse was focusing on wealth management but at the same time trimming the portfolio in developed markets. It was getting out of wealth management in the US, for example, where it had a mere 275 advisers, compared with close to 10,000 at UBS. It had already cut private banking in Germany and was now retreating from the mass-affluent sector in Italy.

The growth engine would be entrepreneurs in Asia, eastern Europe, the Middle East, Latin America and Africa. But one thick strand of the anchor rope to the home market would be sliced.

I stood up at a town hall and said: ‘I’m a New York investment banker and I believe in this strategy. We have a mandate to grow IBCM’s headcount, revenue and market share'

As Thiam now explains his thinking at this phase of the restructuring of Credit Suisse, the IPO of the Swiss universal bank was an emergency option, one that he wanted to show as a possible move but that he never intended to pursue. Few people took much notice that it was always described as a potential IPO, seeing this as an acknowledgement of any new issue’s dependence on calm equity markets to proceed.

“The insurance part of my brain was very used to thinking about contingent liabilities,” Thiam tells Euromoney. “I now realized that what we needed was a contingent asset, something that had the potential for us to monetize on a sufficient scale and rapidly enough.

“The option to IPO part of the Swiss business may have been actually one of the best ideas I have ever had in my business career because it killed several birds with one stone. It allowed me to convince the market that I had a fall-back in case of a worse-than-expected outcome with the DoJ. It also gave me a rationale to drive through a number of absolutely necessary changes in our Swiss business, which now had to be made ready to be potentially IPOed.

“Finally, it avoided immediate further dilution of the shareholders after the fourth quarter of 2015 capital raise, giving us some time and air cover to start implementing our restructuring. Over time, our progress on execution and settling with the DoJ at the lower end of market expectations allowed us to evaluate again all of the capital-raising options available to us.”

If you come out and say: ‘This is only a back-up plan’, then it has absolutely no chance of being taken seriously, of course. But at this point, Euromoney no longer knows what to believe, having reported first on the announcement of the IPO plan, then met executives preparing for it and finally picked up early in 2017 that it was going to be ditched. Thiam is now telling us the secret plan all along was never to do it.

“Sometimes leaders must be willing to live for a significant period of time with letting other people think they are not so smart,” he says. “In this case, I had to live for a long time with a lot of people thinking that I did not understand a concept as simple as dilution – ie that an IPO of the Swiss business was dilutive.

“I did want to run the Swiss universal bank much more efficiently. Preparing for an IPO was a very effective incentive for people to get on with that.”

As he speaks, Euromoney thinks back to his attitude to the UK business of Prudential – the head office expecting priority over new growth engines and starving them of resources.

If Thiam was also reminded of this, he played the new executive team at the Swiss universal bank under chief executive Thomas Gottstein, a former ECM banker put in to run a business preparing for flotation, beautifully.

Thomas Gottstein, CEO of the Swiss universal bank at Credit Suisse

“Come the start of 2017 when we could see progress all around the group and having resolved our DoJ issue in December 2016 – which to be honest was our largest liability – I went back to them and said: ‘Look you’ve done such a good job preparing this business for an IPO that we would be crazy actually to sell it now,’” he recalls.

Credit Suisse went with a second rights issue instead, raising SFr4.1 billion in June last year.

“An IPO of the Swiss universal bank would have been more dilutive to earnings than a straight capital raise, so when investors saw another rights issue rather than the IPO I think they were relieved,” says Thiam.

'Something went wrong'

It is quite a story and a reminder to some of the options traders forced out of the bank in 2015 and 2016 that they might just have been playing poker against a master bluffer. It also casts an intriguing light on the discussions between Credit Suisse and the US Department of Justice in 2016.

But before he could move on to those life-or-death discussions over a final settlement – the DoJ had talked about a penalty of $7 billion, plus some form of consumer relief – Thiam had other internal battles to win.

Needled at his very first press conference in March 2015 by a question asking if Credit Suisse had designated an incoming chief executive who didn’t really understand investment banking, Thiam had bristled.

He went over his education.

“I’ve studied physics and maths. And frankly the maths behind derivatives are a relatively primitive version of that.”

He pointed to his consulting career, when he had reorganized many investment banks. And he reminded his questioner that Prudential had been running one of the biggest hedge books in North America at $120 billion.

“I am very confident that I can understand everything the investment bank does.”

Somehow the subsequent reporting of his answer slightly rephrased it, so that he was quoted saying there was nothing in investment banking he didn’t understand.

It is perhaps revealing that his own response to the charge of lack of investment banking experience immediately focused on derivatives valuations. He was not due to take over until the end of the second quarter, but it was already obvious where his concerns lay.

Credit Suisse made false and irresponsible representations about residential mortgage-backed securities, which resulted in the loss of billions of dollars of wealth and took a painful toll on the lives of ordinary Americans

Thiam unveiled his strategic overhaul in October 2015 with a reduction in RWAs consumed by global markets. The group then completed a SFr6 billion capital raising in December 2015, comprising a SFr4.7 billion rights issue and a private placement. At this point the IPO of the Swiss business was still scheduled for the second half of 2017.

Thiam had been determined to run down legacy positions, but in February 2016 the bank announced trading losses of $633 million from the fourth quarter of 2015, stemming mainly from distressed credit and structured credit. This looked like a bad stumble.

Thiam had to admit at the time: “In fixed income, GM has a legacy of material positions in segments of the market where spreads increased significantly in the fourth quarter of 2015 and where liquidity diminished. These positions have been reduced aggressively since we announced the new strategy. Nevertheless, some positions were still significant at the end of the fourth quarter resulting in inventory mark-downs.”

He promised that: “Our focus will be on continuing to make the fixed income business model significantly less volatile and inventory dependent along the lines of our successfully transformed equities business.”

Then in March 2016 came an unscheduled announcement of further trading losses during the first quarter; what looked like an accusation that these stemmed from positions that had not been properly disclosed; promise of an accelerated run-down of legacy exposures; and even deeper cuts in GM RWAs, as well as in bonuses and in jobs.

“Clearly something went wrong. We’ve since then been looking at that very closely,” Thiam told analysts on a call.

“Internally, the scale of those positions was not widely known,” he added, saying that there had already been “consequences” for some people when they came to light.

The year-old, slightly misreported claim that there was nothing in investment banking he did not know about came back to haunt him. It seemed that while Thiam might well understand the concepts of investment banking, there were, after all, still things going on in the investment bank he presided over that he did not realise.

Jim Amine, chief executive of IBCM, and the only surviving business head still on the bank’s executive management committee from the days of Dougan – when he was one of three co-heads of an investment banking division that also included markets trading, along with fixed income chief Gael de Boissard and equities head Timothy O’Hara – offers a partial explanation in the form of a contrast between Thiam and his predecessor.

“Brady Dougan knew all the numbers,” says Amine. “He was so into the details. Sometimes businesses struggle to summarize data for senior executives, but Brady would say: ‘Don’t give me the summary, just give me all the data.’ He would then work through it all himself.

Tidjane Thiam with Brady Dougan

“Tidjane Thiam is very focused on strategy, with identifying opportunities, deciding the path forward and appointing people to execute, both empowering them and holding them accountable. He’ll push you on strategy and how you’re positioning the business. He has a relentless focus on execution, as evidenced by the results.”

Sources who worked for him at Prudential recall quite a formal chief executive who believes in the chain of command and not one likely to call down to reports three or four levels below the business division heads behind their backs.

If the trading losses and the lack of clarity on the underlying positions really had come as a shock, Thiam now sounds almost pleased that it happened.

In Euromoney’s experience, traders can be very convincing at explaining how complex positions were put on for all the right reasons and that senior management should not listen to the siren voices urging they be cut, just because markets have temporarily turned against them. This will mean crystallizing a reported loss at the worst moment and looking like fools instead of waiting for the markets to come to their senses and naturally carry positions back into the money.

Amine thinks back to the start of the financial crisis. Dougan’s instinct was not to fall for any of that.

“At the start of the financial crisis, we cut our risk exposure early and often, when only one other bank was doing the same thing,” he says.

He doesn’t name them, but it was Goldman Sachs.

“We were selling large amounts of risk in late 2007 and through 2008. Brady Dougan and the board were courageous to allow us to do it. Everyone was telling us: ‘You’re making a terrible mistake, markets will snap back.’ As a result, we were better positioned than our competitors coming out of the financial crisis.”

But trading came to dominate, perhaps emboldened by this initial success and falling for the myth of its own infallibility, with an excess of long-dated derivatives put on with hedge funds and institutional investors. The echoes of Deutsche really are everywhere.

Thiam also thinks differently to the traders and actually more like Dougan.

“What I learned at Prudential was that when you have an asset you don’t want, just get rid of it,” Thiam tells Euromoney. “Traders will always say their books are going to recover and don’t close them at the worst point. But the world is random. So don’t waste time trying to predict it and pick the bottom or the top of the market for that matter. What happened at the end of 2015 was that the very toxic stuff they wouldn’t sell because it was producing earnings for them blew up. Of course, the losses went to shareholders.”

It was symptomatic of a long-standing problem with how the company had been managed.

“Historically, a lot of trading businesses have produced better outcomes for executives than for shareholders,” says Thiam. “If you run a model where a lot of the upside goes to the managers and most of the downside to shareholders, it’s a bit like giving a free option to the managers. Why should shareholders bear the cost of buying options for management?”

There are now only four layers between senior management and the client. It is important that our clients feel the personal touch, that we are close to them

What looked like a serious setback for Thiam to the outside world destroyed the credibility and influence of any remaining internal opposition.

“From that moment on, I was even more determined to execute against our new strategic objectives,” he says.

There were, of course, the inevitable rows about pay. The other favourite game investment bankers and traders traditionally play – alongside ‘my positions were sensible’ – is to let it be known that they will all leave if senior management doesn’t pay them in line with rivals, and good luck by the way managing down all the toxic stuff we’ve left behind if everyone does walk out.

“One of the key moments was at the end of 2015 and start of 2016 when there was a lot of discussions around compensation,” says Mathers. “Previous management always used to blink. But this time Tidjane just didn’t. And it’s good that he didn’t, because this was an important message for the whole bank about cost discipline. For businesses that had missed their targets, there need to be consequences.”

It went down about as well as could be expected. Not only did some bankers have their pay cut, but much of it comes in deferred equity – which mentally bankers price at par when their packages are first struck.

In March 2015, when Thiam’s appointment was first announced, Credit Suisse shares traded around SFr25, rallying strongly on that day in recognition of his achievements at Prudential. But by the end of 2015 the price was down to around SFr20 and in the first months of 2016, as markets absorbed the losses and fretted that the restructuring was not working, the shares collapsed to under SFr13 in February and just under SFr10 in July.

So as well as seeing their nominal pay cut, the value of the deferred equity had halved. A lot of traders in New York complained loudly, including to their institutional clients, some of whom were also shareholders of the bank.

“There was clearly an adverse reaction to this change,” Mathers admits, “but it’s established a much more disciplined culture.”

Amine recalls it well too. His former co-head Gail de Boissard had already left. Now alarm spread.

“We did see a significant pick-up in attrition in 2016 as a result of the reduced compensation in IBCM for 2015” admits Amine. “In addition, the value of the employees’ deferred compensation materially decreased. Those were dark days in early 2016. Some people who had been here for many years were asking: ‘Is this still a place I want to be?’”

Jim Amine, chief executive of IBCM, Credit Suisse

O’Hara, head of global markets, was next to go. Brian Chin, then a 13-year veteran of the firm and a former head of securitized products and co-head of fixed income, was promoted in his place in 2016 to run what would be an even smaller division.

The speculation now was that Thiam might have, in investment banking speak, lost the building, rather like a football manager who has lost the dressing room and whose ouster is merely a question of when, not if.

In fact, converts were rallying to his vision.

“I felt when Tidjane became CEO that this might be a natural point for me to leave the firm,” says Amine. “However, we spent a lot of time talking about his vision for the investment bank, and although many observers speculated that we would have very different views, we were actually completely in sync.

“Global investment banking revenue has been more or less flat since 2008. He didn’t see it growing very much and wanted to know if I saw things differently. I did not. We both agreed that the best strategy for Credit Suisse was to grow its wealth management business, particularly Asia and emerging markets, which were the fastest growing markets. For global markets, there were parts of the sales and trading business in secular decline that were capital intensive and required a lot of technology investment that we decided should be reduced.”

But this was not an outright withdrawal.

“Although we cut back in a number of markets businesses, there were areas relating to IBCM corporate, financial institution and financial sponsor clients that had low complexity and good returns that we should be investing in,” Amine points out.

It was a distinction not immediately evident inside or outside the bank.

“So, when we scaled back global markets, our competitors were telling clients that Credit Suisse was getting out of investment banking and people here were getting concerned about our commitment to the business,” Amine says. “I stood up at a town hall and said: ‘I’m a New York investment banker and I believe in this strategy. We have a mandate to grow IBCM’s headcount, revenue and market share.’

“And we’ve done that over the past two and a half years. My core management team has stayed. We’re hitting our numbers. Compensation has been fair. And we’ve been able to hire significant numbers of managing directors from other US firms because they see we are performing.”

There has been considerable turnover on the executive management committee, but the executives now heading the business units – Amine at IBCM, Gottstein at the SUB, Chin at global markets, Helman Sitohang running Apac and Iqbal Khan, head of IWM – were all previously at the firm.

Thiam brought in just one old colleague from his days at Prudential and Aviva, Pierre-Olivier Bouée as chief operating officer. He has promoted a new, younger cadre.

Standing up to bankers

It seems important to Thiam to have won the trust of long-standing insiders.

“There are two types of CEOs,” he tells Euromoney, “the type that wants to carry on doing what an organization has always done and the type that wants to improve things materially.”

Thiam is the second type. “When that second type comes in, the insiders will watch to see if you really mean business,” he says. “And those who resist change will try and oust you.”

But Thiam has inner reserves to draw on. He tells a story from his time in government in Côte d’Ivoire in 1994. He had come back from France, where he had graduated from École Nationale Supérieure des Mines and gone on to be a consultant at McKinsey, to join the cabinet of president Henri Konan Bédié. While nominally running the National Bureau for Technical Studies and Development, Thiam was negotiating with the IMF and World Bank, working on privatization and overhauling power generation.

Our cost-income ratio is now down to 58% and we’ve gone from being one of the less efficient banks in Switzerland by that measure to one of the best

“We had done a 50% devaluation of the currency in early 1994,” Thiam recalls. “That’s hard. The only way to control inflation is then to be tough on salaries. I was asked to explain this to a meeting of student leaders. Students were paid a state salary. It was like a meeting with a union of state employees. They were angry and some of the students were capable of violence.

“The prime minister told me that various government colleagues who were also meant to attend had cancelled and asked me to accompany him that Saturday morning. We had security guards. I looked at them and could see that even they were worried. I walked into the meeting with the prime minister to explain the situation. The student leaders were saying: ‘The government is against the students.’ And I had to say: ‘Well the students are against the population who don’t get a subsidy. We want to put electricity in every village because when we do that, school results go through the roof and it improves everyone’s life. We will also be able to build more primary schools to increase the school enrolment rate.’”

He was 32 years old. Now in his early 50s, derivatives traders complaining about disappointing bonuses were never going to get much more than a raised eyebrow and a sceptical stare.

But there were others Thiam wanted to win over.

“When I arrived, I decided to develop the strategy with the existing management team and do my people evaluations by working with them on it for the first three months,” he says.

“That was quite deliberate. The answer is always inside a company. As a leader, the challenge is to find those people who have the answers and to listen to them. There are always people inside the company who know exactly what needs to be done.”

'There is no plan B'

It was at times difficult and painful to win round other veteran insiders and shareholders, who had been used to hearing from senior executives that the bank did not need to tap them for capital. But even as the restructuring began to make progress in 2016, a far tougher audience lay in wait.

On a one-to-10 scale of intimidation ranging from violent student leaders at 10 and overpaid traders who have been rinsing the company for years complaining about poor bonuses at a two, dealing with the US Department of Justice over RMBS settlements appears to rank about 8.5.

Under-reserving for this was one of the reasons why Credit Suisse now needed a capital cushion that it had not been able to generate from retained earnings.

Before meeting attorney general Loretta Lynch to discuss a potential settlement in September 2016, Thiam recalls sitting down with the bank’s legal advisers. “I asked the lawyers: ‘What’s our plan B?’ I never like to do anything unless there’s a plan B. And they told me: ‘You’ve just got to go and explain our situation to her. There is no plan B. Sorry. You must succeed in convincing her, period.’”

Loretta Lynch

As a new chief executive and a non-banker with prior experience in public service, Thiam at least could be very honest about what the bank had done wrong. He could also point to its history, its importance especially to Switzerland and the number of livelihoods that depended on its continued existence.

“I talked to [assistant attorney general] Bill Baer,” Thiam recalls. Baer was a scourge of the banks through the RMBS working group, describing their misrepresentations, lies and disregard of the law as a stunning breakdown in ethics.

“It turned out that we had both been around the World Bank at the same time, and though our paths had not crossed we knew some of the same people in Washington and at the World Bank,” Thiam says. “I talked about what I had tried to do in government in Africa. I think he respected that.”

In 2016, Lynch and Baer held the fate of Credit Suisse in their hands.

Maybe what Thiam managed to convey was a sense of the bank’s vulnerability and weakness. This after all was something of a fallen giant, the Swiss owner of the once renowned First Boston, now so desperate for capital that it was having to press ahead with this crazy plan to IPO its own Swiss business.

Regulators and prosecutors had waited years for banks to recover and start earning again after the sub-prime collapse of 2008 before hitting them up for big settlements. But they didn’t want to force big banks out of business and set off a new systemic crisis.

Lynch was scathing.

“Credit Suisse made false and irresponsible representations about residential mortgage-backed securities, which resulted in the loss of billions of dollars of wealth and took a painful toll on the lives of ordinary Americans,” she thundered.

The fear had been of a penalty of $7 billion or more. In the end, the DoJ announced a $5.8 billion settlement, crucially with just $2.48 billion in civil penalties and another $2.8 billion in relief including loan forgiveness and other remedies to be paid out over five years. This consumer relief had minimal immediate impact on profits and the capital position.

Big losses to pay for the $2.48 billion penalty would follow the previous losses on toxic balance sheet positions, but the bank would survive and Thiam and his team would have the chance to proceed into the second year of their restructuring and show what Credit Suisse could do.

Thiam had placed his faith in Mathers, putting the CFO in charge of the run-down of the strategic resolution unit. It sounds like a bit of a hospital pass, but, looked at in pure RWA terms, this was one of the bank’s two biggest businesses. At the start of 2015, it accounted for SFr56 billion of RWAs, excluding operational risk, and SFr219 billion of leverage exposure.

“The SRU has been absolutely key to the whole restructuring,” says Thiam. “I was going to take it on myself. But then I thought: ‘No, I’ll give it to David’. No one better knows the level-three assets and other stuff in there. And since I took that decision, he has done a phenomenal job working it down.”

Thiam adds: “You might say we have been lucky that markets have let us sell down at modest losses of maybe 1%. But the key point is that pushing it out quickly is the right decision. You make your own luck. If you get out at a 1% loss, that’s great. It would still have been the right decision even if it had cost us 5% – which was the top of the 3% to 5% range we guided to – rather than the 1% we achieved.”

For his part, Mathers also weighs option values.

“The different business units of this bank now have a laser-like focus on cost and efficiency improvements,” he says. “The biggest part of the overall cost reduction has come from the SRU programme where we exited from marginal businesses and positions. This includes shutting down redundant IT systems as we exit. I wanted to have people with me who will kill applications and permanently cut the expensive luxury of unnecessary optionality that so many banks like to retain.”

When Euromoney went to press on the eve of the second-quarter results, the SRU accounted for just SFr12 billion of RWAs, excluding operational risk, and SFr45 billion of leverage exposure.

It has shrunk by 80% in three years and the costs of running it have fallen at a similar rate.

While group profits are only now returning to the level they stood at three years ago, Credit Suisse is today wringing these from much lower risk.

In the first quarter of 2015, Credit Suisse had a common equity tier-1 ratio of just 10% and daily value at risk was SFr46 million. Fast forward to April this year and CET1 was up to 12.9% while daily VaR had come down to SFr29 million. Having built up high-quality liquid assets in 2016 in preparation to withstand any short-term loss of creditor confidence from a harsher settlement with the DoJ, Credit Suisse has since maintained a group liquidity coverage ratio of over 200%.

Pulling together

Credit Suisse's people now share a clear sense of the bank’s identity and its mission.

Other bank chief executives are often decent judges. One tells Euromoney: “Credit Suisse has done a good job of turning itself around and looks set to come through better than most people think. I love its private bank. I only wonder whether Thiam has rather imposed himself on Credit Suisse and not yet carried its people with him.”

To the outsider, the six-business-unit structure looks complicated, compared with the days when Credit Suisse reported as private banking and wealth management on the one hand and investment banking on the other. Today, geography seems to have taken the lead over products, so that, for example, both the SUB and Apac each combine elements both of wealth management and investment banking that together probably rival or exceed what reports as wealth management in IWM and investment banking in IBCM.

Thiam, needless to say, disagrees: “The old investment banking division had three co-heads and private banking and wealth management had three heads. Now I have six divisions each with their own CEO who is responsible for everything, including IT and operations. How is that more complicated than what came before?

“I believe that greater accountability comes when there are leaders accountable for specific clients, and each client I know is based somewhere, in a specific geography,” Thiam explains. “That is why I want each of my CEOs to be accountable for and be empowered in a specific geography. If I hear of a problem, I can call them up and deal with it more easily than going to a global product head. If there is a problem with a client in Switzerland, I know exactly whom to call and that is Thomas Gottstein, CEO of Switzerland. If there is a problem in Asia, I know whom to call and it is only one person – Helman Sitohang, CEO of Asia Pacific. And the same principle goes for the whole bank: accountabilities are very clear internally and externally, which can only be a good thing.”

Thiam is not the first chief executive to realize that the difficulty with running global businesses is that key clients want to deal with local executives that have the authority and financial capacity to serve them. Perhaps more important is that, in restructuring the business, he has promoted an emerging generation of leaders that appears to be thriving in Credit Suisse’s new flat structure.

Iqbal Khan, chief executive of IWM at Credit Suisse

“There are now only four layers between senior management and the client,” Khan, chief executive of IWM, tells Euromoney. “It is important that our clients feel the personal touch, that we are close to them. This proximity improves time to market when delivering sophisticated solutions. Also, it provides support when communicating decisions.”

He offers an example: “We had a client coming to us with a specific opportunity. We looked into it and had to say actually we needed to pass this, along with an appropriate explanation. The client came back and said: ‘Thank you for giving me a clear answer within 12 hours. I’m being passed from pillar to post at some other banks who still haven’t been able to give me a proper answer after two weeks.’”

Khan draws an important lesson from this: “Sometimes when you tell clients what you can’t do for them, that actually enhances your credibility.

“Our house view and investment calls outperformed competitors and are the anchor point to engage with clients,” he says. “However, every Credit Suisse client presentation includes what investment calls we got just wrong as prominently as investment calls we got right.”

There are other examples of how this new coverage model works to the bank’s benefit.

“A major proportion of net new assets comes from existing clients,” says Khan. “For example, we were in a meeting with a client and explored his needs as an entrepreneur. We can offer sophisticated one-stop-shop solutions for business needs and private wealth. Our unique international trading solutions offering often serves these needs. This client turned out to own multiple companies with their own cash flows. He knew I had been a CFO and we started talking about asset and liability matching. After multiple subsequent meetings, we ended up working through a $1 billion ALM strategy for his portfolio of companies.”

Khan says: “I see two clients every day and I love doing it. I have no managers that do not enjoy client meetings. We are very hands-on.”

IWM was a SFr1.1 billion pre-tax income business in 2015. It hit SFr1.5 billion in 2017 and the target is SFr1.8 billion this year. It could close to double in three years. It still does plenty with high net-worth clients. They gave the business its scale. Picking up an extra SFr100 million or SFr1 billion here or there from an UHNW client that has met a member of the executive board is the juicy growth on top.

Is the battle to build a new model of wealth management won?

“We cannot and shall not become complacent,” says Khan. “In any case, the numbers are not the goal: they are the by-product of doing business the right way. We significantly upgraded our client coverage teams in the past three years, while also focusing on risk-reduction and tax regularization. I would have expected to lose productivity during such a time. In fact, we are growing assets faster than ever.”

Pulling together

There is a feeling that Credit Suisse is pulling together more now than ever before. Its global markets business still has plenty of smart traders. While they were focusing on hedge funds and institutional asset managers in the past, they didn’t seem to do so much for the private wealth management side of the business.

Now, through a new joint venture called ‘international trading solutions’ (ITS), the markets side of Credit Suisse is constructing new investments for the high net-worth and UHNW clients the bank already had a leading franchise to serve. ITS has offered structured investments – a carry note on hedge fund indices or a note linked to the return of a credit portfolio – sometimes attracting billions of dollars’ worth of subscriptions in short marketing periods and subsequently adding more bespoke structured variations for particular clients.

There has been an internal debate as to whether Credit Suisse might have ended up subscale in global markets and could now do worse than give it another $10 billion of RWAs or another $1 billion of capital.

In the first quarter of 2015, GM had accounted for close to $130 billion of RWAs, just over half the group total. By the end of the first quarter of 2018, it was down to just under one third of the group total at $61 billion. Is it time to ease back a little?

“We prioritized capital allocation to our wealth management businesses, higher returning advisory and capital markets operations, and, within trading, businesses closely aligned to our clients and strategy,” says Mathers.

All good CFOs like to run businesses so they are always hungry for capital. It seems obvious that within GM, it is ITS that is likely to get more.

In IBCM, meanwhile, Credit Suisse is a long-time leader in leveraged finance, competing with the biggest global banks to provide funding to large private equity sponsors on the look-out for attractive assets.

A private bank dealing with entrepreneurs can put itself right at the centre of some interesting flows. Credit Suisse’s UHNW clients are often the owners of companies the sponsors want to buy. They have long invested in the sponsors’ private equity funds, providing a big chunk of the funds leveraged up to buy each other’s companies.

There is a sense of much more to be done here: not just in managing and diversifying the wealth of entrepreneurs who realize it when they sell their businesses to financial sponsors, but also bringing UHNW clients investment opportunities in private debt as well as private equity.

Once more, Euromoney asks if only an outsider could have got the bank working together like this.

This time the answer is different.

“Absolutely,” says Khan. “Tidjane Thiam has transformed this bank.”

Running for the IPO that never came

Thomas Gottstein had worked his way up at Credit Suisse, having joined from UBS in 1999, first as an investment banker. He was then appointed head of equity capital markets in Zurich and later London-based co-head of ECM for EMEA, before being appointed to run the Swiss universal bank in 2015 and told to prepare it for an IPO.

“At the time, we needed a solid plan for raising another SFr5 billion ($5.04 billion) of capital during the time period 2016/17,” says Gottstein. “As we hadn’t settled the RMBS issue then, the Swiss IPO was the only alternative where we were in full control.

“Our cost-income ratio in Switzerland in the years 2012 to 2015 was between 68% and 70%, which Tidjane and I considered substantially too high and which we wanted to improve to under 60%. The IPO preparations helped me put a lot of focus on my management team to cut costs and improve profitability.”

Gottstein and his team had a year to create the new Swiss legal entity. But then plan A was revealed really to have been plan B all along. And now plan B was cancelled.

Euromoney hears that Gottstein had to tour each Swiss region to explain to executives – who sometimes felt domestic profits were being diverted to pay fines for others’ misdeeds and to subsidize bonuses elsewhere and had been looking forward to a little independence – why this was no longer coming.

Does he harbour any regrets?

“No,” he says. “It was the right decision as it is a core business of the group and the complexity would have been quite material.”

The story had been put about that the Swiss business was raising capital to mint a currency for domestic consolidation. But with only 30% floated and the chief executive and chair of Credit Suisse likely to be powerful voices on the board of a partially floated SUB, it was never going to be able to plough its own furrow.

“The way to win internal and external stakeholders over is to point them to improving performance,” says Gottstein.

In the first quarter of 2015, the SUB made SFr431 million of profit and a 14% return on regulatory capital. In the first quarter of 2018 that had risen by 29% to SFr554 million of profit and an 18% return.

Can this continue?

“A lot of the improvement in profitability has come from the cost side,” Gottstein says. “Our efficiency measures were broad based and included automatization, de-layering, flatter structures and fewer branches. Our cost-income ratio is now down to 58% and we’ve gone from being one of the less efficient banks in Switzerland by that measure to one of the best. But we also want to grow the top line by further investing in people, digitalization and automatization.”

If Credit Suisse can turn the steady and stable anchor division of the group into a growth story, that will be some achievement. It remains to be seen but plans are in progress, not least in doing more with Swiss small and medium-sized enterprises. And for the first time in years, bolt-on acquisitions may be back on the agenda.

“Whilst further growth is a challenge in a mature market with negative interest rates,” says Gottstein, “we see potential for more client activity through better service excellence and to further participate in the consolidation through organic or, potentially, inorganic growth moves.”

Lessons from a turnaround

It must have been quite a class. Tidjane Thiam graduated from École Polytechnique in Paris along with three other men who went on to be chief executives of large European banks: Jean-Laurent Bonnafé, head of BNP Paribas; Jean Pierre Mustier, head of UniCredit; and Frédéric Oudéa, head of Société Générale. One wonders what they must have been like to teach. Competitive, do you think?

After Polytechnique, Mustier and Thiam – who had both also attended École Sainte-Geneviève in Versailles, France’s leading Jesuit preparatory school – both went to the École Nationale Supérieure des Mines in Paris.

Thiam doesn’t mention it, but Euromoney checks and finds that he graduated top of his class before going on via Insead and a one-year stint at the World Bank in Washington to another great training school for bank chief executives – McKinsey.

There, Thiam worked on bank restructurings, learning from his time in the trading business at JPMorgan and consulting on the merger of Chemical Bank and Manufacturers Hanover in 1992, which later rolled up the better-known Chase Manhattan and eventually took over JPMorgan itself.

He rubbed shoulders with other rising McKinsey stars who have gone on to be chief executives, such as James Gorman, chief executive of Morgan Stanley.

Perhaps that is why he told reporters at the press conference in March 2015 to announce that he had been designated to take over as chief executive of Credit Suisse in the second half of the year that this move from the Prudential would allow him to complete something: his destiny perhaps?

He had taken an unusual diversion, leaving Paris in 1994 for five years in economic and planning roles in the cabinet of Henri Konan Bédié, president of Côte d’Ivoire. Thiam had come from a political family and stayed on until a coup overthrew the Bédié government in 1999, returning to McKinsey now as a full partner and one of the leading members of its practice covering banks and financial services firms.

After joining Aviva in 2002 and rising to chief executive for Europe, he left after five years and became first CFO of Prudential and then soon after chief executive, when Mark Tucker stepped down from that role. Tucker, of course, went on to head AIA, which Thiam tried to buy from AIG before the rescued American insurance giant floated the business instead to pay back its US government bailout.

Thiam has walked in this exalted business company all his working life and is offended that questions were raised about his capacity to run Credit Suisse.

Thiam passed his 56th birthday at the end of July. It is impossible to know how long he will stay at Credit Suisse. He is capable of the elliptical sound bite.

“In business in general, I think you can only build long-term, sustainable success if you are riding some kind of secular wave or trend that has to do with the real economy,” he says. “And then you also have to execute well. Your business model can’t just be to be smarter than the next guy.”

Wherever his career takes him, people will ask about the lessons of the three-year restructuring now heading towards completion.

“I don’t know of any CEO who has said: ‘I wish I hadn’t tried to do so much in the first months,’” he tells Euromoney. “If you need to do a restructuring, it certainly cannot take more than three years.

“And you cannot do this kind of restructuring incrementally, otherwise you will fail. We set out to do 50% of the costs cuts and other changes in year one, 30% in year two and 20% in year three. The first year was very tough, but that makes it already irreversible. And then you can tell your people the pain will be 40% less in the second year. After year two: ‘We are 80% done already.’ And after that: ‘Come on guys, we only have one last push to go for the last 20%. Let’s not become distracted and blow it now.’”

Thiam says that some voices advised him to go in softly, to take time to fully understand every aspect of the business.

“That’s the kiss of death,” he says. “You’ll have no chance. If you try and do one third of what needs to be done in each of three years, by year two you will have lost everybody and not achieved enough. People see no improvement, no momentum from one year to another. The amount of pain is the same every year and they get discouraged.”

He doesn’t sound like he is planning to slow down or go to the next big challenge soon. Maybe he fancies a stint at being that first type of chief executive, that just nurses along a business franchise that is well set. “It’s taken three years, the beginning of which was a nightmare, to help this fantastic bank emerge,” Thiam tells Euromoney. “I now want to have some fun continuing doing this.”