The kaleidoscope effect: Global risk is constantly shifting

In Q3, risk scores for more countries improved (63) than worsened (53), but the downgrades were quantitatively larger and concentrated among emerging markets (EMs), highlighting the risk aversion that prompted capital outflows and currencies to buckle earlier in the year.

Broad-brush comparisons reveal unweighted average risk scores for Brics and Mints declined in Q3 (indicating higher risk).

Geographically, there were falls for Latin America, the Middle East and Africa, but not sufficiently to wipe out year-to-date gains, with Europe improving thanks to positive economic trends:

Euromoney’s risk survey is conducted quarterly among more than 400 economists and other experts – both financial and non-financial sector based – with the results compiled and aggregated along with other relevant investor risk data. They include sovereign debt statistics and judgements on accessibility to bank finance, and international bond and syndicated loan markets.

These various quantitative data and qualitative assessments are compiled and weighted according to relevance to provide total risk scores and rankings for 186 countries worldwide.

Several countries with declining score trends were marked down further during the quarter.

They include perennial concerns South Africa and Turkey, as well as Gulf states slowly recovering from the oil crisis but affected by low growth, fiscal challenges and fallout from the diplomatic and political boycott of Qatar.

And risk scores for a number of higher-risk opportunities, including Iran, Pakistan, Sri Lanka and Yemen, were similarly lowered.

Dominant themes

The big thematic shifts in the global risk environment are happening in three areas, says ECR survey expert Constantin Gurdgiev, professor at the Middlebury Institute of International Studies (MIIS).

“[They are] the ongoing macroeconomic crisis in emerging markets, the divergence in growth dynamics between the US, euro area and the rest of the world, and mounting geopolitical and trade tensions between the US and China,” he says.

EMs are a considerable focus, but the EM asset class is a disparate one based on key risk fundamentals and there are competing views as to whether the situation is likely to worsen or improve.

Noting the fact capital inflows revived in September, the Institute of International Finance (IIF) has, in its own words, “turned more constructive on emerging markets”, given that the sell-off eliminated some of the biggest FX overvaluations.

Moreover, the IIF does not believe US monetary policy is a negative EM catalyst.

“Markets are pricing close to what the Fed says it will do through end-2019,” the IIF says in a recent report, “[and secondly,] there is little sign the Fed is behind the curve on its macro forecasts, so a hawkish shift based on labour market and inflation dynamics is unlikely.”

Euromoney’s risk survey, to a large extent, reflects this. Some EMs are of concern, but others are showing resilience; there is not, at least not yet, a general decline in confidence.

ECR survey participant M Nicolas Firzli, director-general and head of research for the World Pensions Forum (WPF), notes that key jurisdictions – including Russia and Saudi Arabia – “were, to varying degrees, victims of unfair, excessive capital flight earlier in the year”.

He believes the commodities’ comeback will make a big difference.

Drilling down into the survey data highlights some notable contrasting trends.

Countries in Asia, which had been improving owing to their strong economies, have become the centre of attention as discussions surround the possibility of another 2013-style ‘taper tantrum’ or repeat of the late 1990s Asian financial crisis.

Risk scores for India and Japan have fallen, as they have for Hong Kong and Singapore, but in the main Asia is demonstrating resilience to what many would describe as routine strains, notably with China (the strongest Bric) holding up as stimulus policies mitigate the risks of trade-related setbacks:

Malaysia, Thailand, the Philippines and even Indonesia – buoyed by an appropriate policy response to currency depreciation – alongside Cambodia, Myanmar and Vietnam have steadied since their scores were downgraded earlier in the year.

Across Latin America, Argentina’s rise has been checked after a return to recession and spike in political risk causing a crisis of confidence and intense currency pressure.

There are also downgrades to Bolivia, Ecuador, Mexico and Uruguay, with Brazil flat-lining, and there is no end in sight to the economic crisis in Venezuela, lying 170th in the global rankings, as unorthodox policies, hyperinflation and mass migration make it one of the highest risks worldwide.

“Emerging markets, especially some key Latin American economies, have experienced a significant rise of uncertainty relating to their capital flows and economic growth in Q3 2018,” says MIIS’s Gurdgiev.

The risk outlook for EMs is dominated by uncertainty surrounding these capital flows, as well as adverse trade dynamics stemming from the US-China trade wars and the US-Iran embargo.

According to Gurdgiev, this is creating, if not among all countries, “significant deterioration in the risk environment across a range of large and globally systemic EMs”.

Room for optimism

The top of Euromoney’s risk rankings has a familiar feel, with Singapore, Norway and Switzerland still rated the safest investor domains worldwide.

Risk perceptions for North America were unchanged in Q3, and generally speaking large parts of Europe continued to show modest improvement – with some exceptions – driven by economic growth linked to external trade and supportive, ultra-loose monetary policies.

Risk scores deteriorated – a little – for Poland and Romania, principally due to their respective domestic political problems.

However, the picture for much of central and eastern Europe brightened further thanks to stellar economic growth, tight labour markets and improving fiscal metrics outweighing institutional risks, or concerns about policymaking or government stability.

In western Europe, a mixed picture is developing as analysts weigh up the global trade environment, inflation and the impact of Brexit, among the various salient risk factors.

Economic activity has continued, but at a slower pace compared with last year, and the European Commission’s economic sentiment indicator for the EU dipped in September to its lowest level so far this year, due to falling confidence among consumers and manufacturers.

The survey shows lower risk scores for the Netherlands (trade-related), the UK (Brexit) and Sweden, where inconclusive elections and the strength of support for the far-right party Sweden Democrats has once again highlighted the rise of populism precipitating political fragmentation.

Elephant in the room

Italy’s score has rebounded since it, too, held elections, as the risks of imminent distress have calmed with a new government formed.

Yet Italy remains by far the riskiest G10 country, lying 41st in the global rankings, well behind Japan in 26th place.

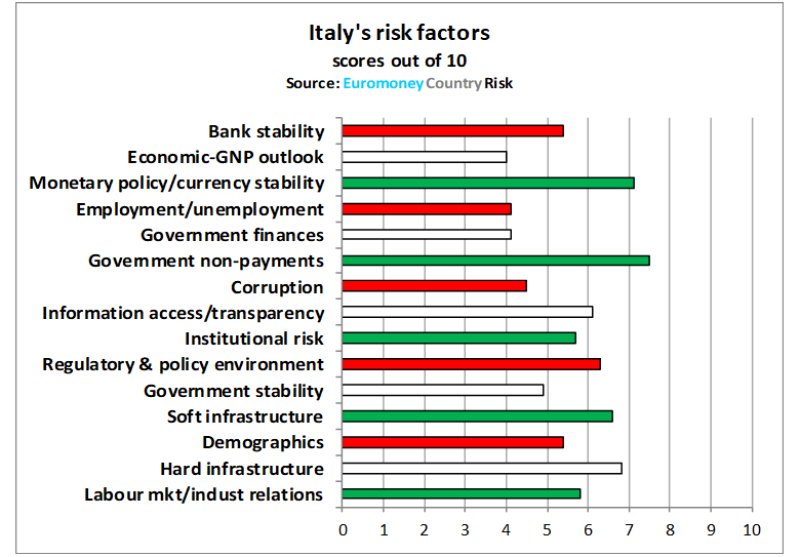

Experts have upgraded the economic and political outlook, but these risk-indicator scores are generally all lower than at the beginning of the year, with structural risk indicators downgraded:

Firzli at the WPF reflects general anxiety among risk experts on Italy, noting how the recent elections have brought to power “unorthodox policymakers whose socio-economic projects diverge visibly from the neoliberal ‘open borders and open societies’ agenda of the past 40 years, and is happening at the worst possible time for the EU bureaucracy”.

Independent economist, risk expert and regular survey contributor Norbert Gaillard’s concern has been heightened since finance minister Giovanni Tria set the fiscal deficit for 2019 at 2.4% of GDP.

“When we keep in mind that GDP forecasts for 2019 are uncertain – because the oil price is going up, Brexit discussions are blocked and international trade flows are slowing, we can doubt the deficit will be lower than 3%,” he says.

For Italy, it is a sizeable structural problem, but the new leaders, Five Star Movement’s Luigi Di Maio and Lega’s Matteo Salvini, “have opted for a morally hazardous policy”, he says, knowing that Italy is too big to fail and expecting the European Commission to be lenient and accept fiscal loosening.

Firzli refers to a “venomous vision of Italy openly mocking the European Commission’s sacrosanct budgetary cohesion, and in the process threatening to compromise the fledgling economic recovery in France, Spain, Portugal and Greece”.

Gaillard states Italy could end up in a “lose-lose game” if international investors are reluctant to purchase its sovereign debt.

And that’s not all.

The global economy is likely to witness a number of potential risk flashpoints through the remainder of the year, warns Gurdgiev.

“These will be concentrated primarily in the EMs and euro area, with key Brics economies flashing red on the risk monitoring board,” he says.

Gaillard also reminds us of the consequences of a hard Brexit, and of the financial and economic turbulence it will deliver during the next few years.

In the meantime, US policies towards China, Russia and Iran are having real effects in terms of undermining economic global growth, despite resilience, and these trends could develop and magnify if trade frictions worsen or are prolonged.

Opportunities further afield

This puts the emphasis on other regions, such as sub-Saharan Africa, which is holding up rather well. As the problems in South Africa continue, elsewhere diminishing political upheaval, recovering commodity prices and creditor engagement are shining the spotlight on the continent again.

Several countries, including Ghana, Nigeria and Zimbabwe, have seen their scores improve in Q3, and only a quarter of the region has been downgraded so far this year.

This matches LatAm, and compares more favourably than Asia – a third downgraded – as well as both the Middle East and Caribbean, where almost half the countries are deteriorating.

The former Commonwealth of Independent States has similarly become safer, despite Kazakhstan remaining out of favour among risk experts. This is mostly due to economic concerns (weak industrial production), as well as uncertainty over the succession plan for when president Nursultan Nazarbayev relinquishes power.

Countries that were upgraded in Q3 include Armenia, Azerbaijan and Moldova, as well as Georgia and Ukraine.

To access the survey and view the latest results: www.euromoneycountryrisk.com