He looks older than his 53 years; his full beard is not naturally black, it is dyed. He is thickset, though not fat. He wears the ghotra, the headcloth, without the agal, the black band that many Saudis wear. He is intensely religious. His secretiveness and discretion are legendary. His name is Sulaiman Abdel-Aziz al-Rajhi, and, although some members of the Saudi and Kuwaiti royal families probably have greater personal fortunes, he is the richest self-made man in the world.

He is richer even than Daniel Ludwig, listed in the Guinness Book of Records as the world's richest man, and by Forbes magazine as the richest man in America. But Ludwig, according to most estimates, is worth only $2 billion since he is reported to have lost $1 billion on his Amazon Basin project. Sulaiman al-Rajhi, on the other hand, is worth $3 billion. That implies that he could buy and sell Nelson Bunker Hunt, and barely notice that he had done so.

You would never know it, of course. His dress is that of a conservative, religious Saudi. The headquarters of his company in the old business area of Riyadh are those of a struggling merchant; carpets are threadbare, offices are divided by inexpensive, functional aluminium and glass partitions, and dotted with plastic-topped tables. His own office is large, but unsophisticated, apart from a screen beaming in the latest money rates from world financial centres.

Sulaiman al-Rajhi is a money changer, the head of the partnership that owns the Al Rajhi Company for Currency Exchange and Commerce.

The personal assets of himself and his three brothers, the four partners — assets available to back the business — are estimated at 24 billion Saudi riyals, or $7 billion. Sulaiman owns 42% of the partnership, worth nearly $3 billion.

Of course, Saudis who accumulate wealth have a major advantage over most other nationalities. Saudi Arabia and other Gulf states do not have personal or corporate taxes. They have virtually no indirect taxes. Instead, they have a 2% zakat, a semi-optional religious tax paid by companies and individuals on the annual increases in their assets. In Saudi Arabia, the zakat is collected by the Ministry of Finance, and spent on the poor. Sulaiman al-Rajhi is the biggest payer of zakat in the kingdom.

He had never spoken at length to a western journalist before his interview with Euromoney. He speaks no English. There are no photographs of him outside his family: partly through shyness, partly for security reasons, he refuses to be photographed. He relishes his anonymity.

Sulaiman Abdel-Aziz al-Rajhi was born about 1930 in the small town of Bukariyah, near Buraidah in the Qassim region of Nejd, in central Arabia. He was among the eldest of a family which has continued to grow and now contains 22 brothers and sisters. His father, Abdel-Aziz, who was a farmer and minor trader when Sulaiman was young is still alive. He is now about 78; his eldest son is 60 and his youngest is two.

The young Saudi learned reading, writing and the Quran. As a small boy he was taken to join the elder members of his family in Riyadh, and a few years later, when he was just in his teens, he began to work for his eldest brother Salih, for a tiny salary — less than $10 a month. This was the beginning of the world's most successful business career.

"I had a special jacket which took 15 kilos of gold on each side."

Salih had begun a little money changing business. At first this involved the extremely simple matter of giving people change for riyals: a man would give Salih a riyal and he would break it down into gursh and halalahs for a commission of 5%.

Soon, Salih began to deal in the numerous different currencies that were in circulation in Saudi Arabia. To people who were given gold by the government, he would sell riyals; to traders who were going to Kuwait to buy merchandise, he would sell gold. In Kuwait the traders would exchange the gold for Indian rupees; with the rupees they would buy goods in the souk. The use of this variety of currencies and the more complicated trade in pilgrim currencies on the other side of Arabia made money exchanging an active and sophisticated business in a very simple economy.

In the later 1940s Salih sent Sulaiman to Mecca. He liked the Hijaz, which, until the 1970s, was a far more prosperous area than the Nejd, and in 1954 he asked Salih if he could open his own business in Mecca and Jeddah. For the next 25 years, Salih and Sulaiman were to run operations almost as if they were branches of the same business. They dealt with each other, used each others’ signatures, and did business on each others’ behalf.

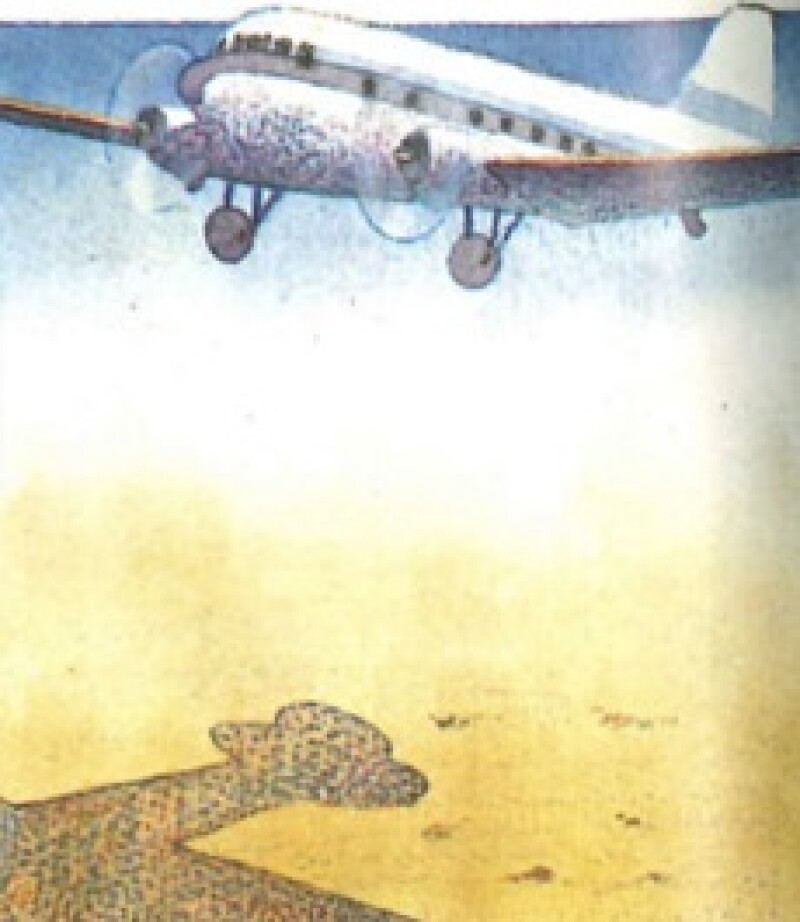

At that time, there were only two flights a week between Riyadh and Jeddah. Each brother met each flight. On almost every flight one brother sent the other a letter, payment instructions, or information on the market.

According to the levels of government and pilgrim business, the prices of gold and silver would vary substantially between Jeddah and Riyadh. In effect the brothers ran an arbitrage business in bullion.

But it was the method the brothers used to send gold and documents to each other that beggars belief today. They simply handed them to a passenger with the request that he should pass them on to a man named al-Rajhi at the other end.

Explained Sulaiman in his interview with Euromoney: “I had a special jacket which took 15 kilos of gold on each side. I would walk to the airport in the evening, dig a hole in the ground, put the gold in it and go to sleep on it. It was as simple as that. In the morning I would get up, pray and go to the aircraft, where I would give it to a passenger. I never asked for a receipt, and we never lost any gold.”

Salih had a longer walk to the airport in Riyadh. Neither of the brothers owned a car in the early 1950s. Both believed they were too expensive to hire. There were no airport hotels then. “And even if there had been one,” said Sulaiman, “I would not have paid what they would have charged.”

That extreme sense of caution over spending on what he regards as needless extravagances continues to this day. When he visited London recently for discussions with a travellers' cheque company, his hosts sent a limousine to greet him at the airport. Sulaiman spurned it, took a taxi, and complained to the British company about its extravagance. Said one of the directors later: “I wish I'd sent a bloody bicycle."

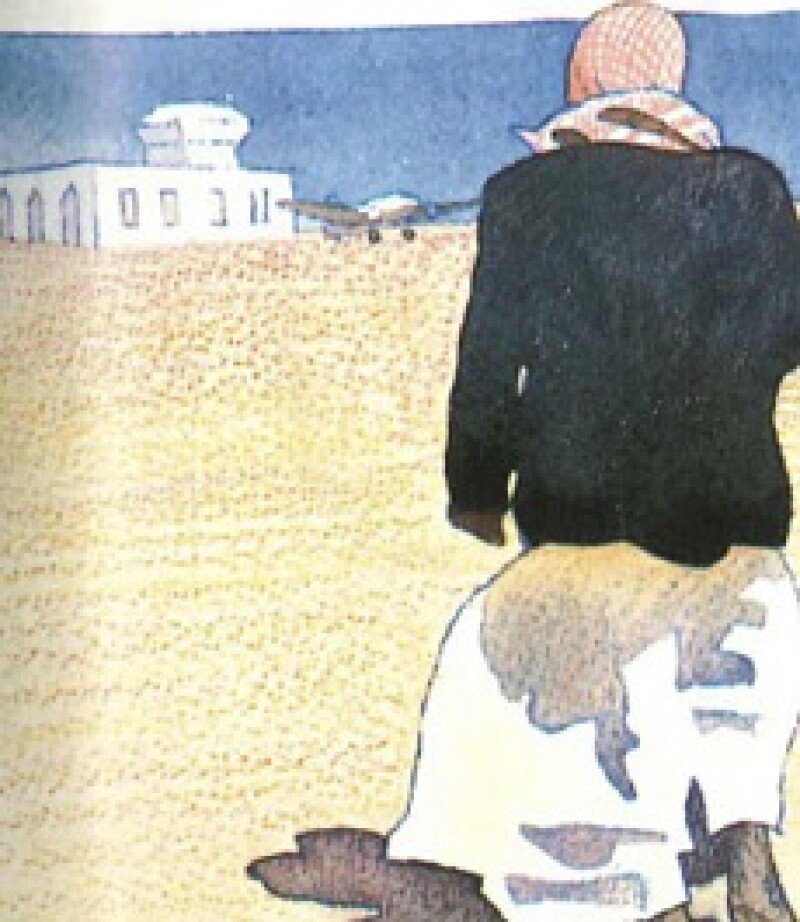

Sulaiman used to walk to the airport...

bury his gold shipment in the ground...

and sleep on it until the morning.

Gradually the al-Rajhis’ businesses became more sophisticated and more international. Salih periodically flew to Beirut and established a working relationship with banks there. He produced his own system of drafts. This involved his giving a letter in his own handwriting to the customer and instructing the customer to present it to his agent in the Lebanese capital. Within a short time a connection had been established through a bank in Beirut with the United States. During the 1960s the Rajhis opened accounts with banks in most of the major centres of Europe and Asia.

As younger members of the family grew older and began to work for their brothers, Salih and Sulaiman exercised a strong influence on their lives. One Of their brothers, Abdel-Rahman bin Abdel-Aziz, who now has a large exchanging company of his own, recalls at an early stage being told by Salih that earning trust — “the love of the people” as he put it in a common Arabian phrase — was more important than mere money. This was for both moral and business reasons.

Sulaiman, for whom Abdel-Rahman began work as a tea boy and apprentice book keeper at the age of 12, insisted that his younger brother should rise and go to the mosque for the first prayers of the day at 4 a.m. He would first knock on the youth’s door; and then, if there was no response, Abdel-Rahman recalled, Sulaiman would enter, and hit him. When Abdel-Rahman left school in the late 1960s, Sulaiman arranged a marriage for him at a week’s notice. By this time the young employee had been entrusted with more sophisticated book-keeping work and was being paid in shares in the Saudi cement and electricity companies, of which Sulaiman was a founder.

At the beginning of the 1970s Abdel-Rahman was sent to manage Sulaiman's branch in Medina, and was then given the job of setting up new branches for the company in the south west of the kingdom. He became a partner with Sulaiman in real estate ventures in Jeddah. Already, the family was being spoken of as one of the richest in the kingdom after the Al Saud.

It was a considerable blow to Salih and Sulaiman when in 1973 and 1974 members of the family began to break away from their businesses. The first to go were two of Salih's 40-odd children, Abdel-Rahman bin Salih and Abdullah bin Salih, who founded the Al Rajhi Trading Establishment and the Abdullah Salih Al Rajhi Establishment.

"I never asked for a receipt, and we never lost any gold."

Then in 1975 Abdel-Rahman bin Abdel- Aziz left Sulaiman to set up his own company in Khamis Mushait in the south west. This was the Al Rajhi Commercial Establishment for Exchange, which has since moved its headquarters to Jeddah. Abdel-Rahman told Sulaiman he had started on his own because Sulaiman's own sons were growing up and would be bound eventually to inherit their father’s company. He explained that he had a family of his own and that he wanted to have a business which could leave them in due course.

The separation of the three younger al-Rajhis from their elders was not happy. All three broke away mainly because they could see enormous business opportunities for themselves through their being able to us the name Rajhi. They had also, apparently, wanted to be partners and not just managers in the existing operations, and to run them on more modern lines.

Salih's and Sulaiman's initial response to the idea of the young establishing separate companies was to warn them that managing a successful money exchange business was not easy — a thought which at least one of the young apparently dismissed.

Abdel-Rahman bin Abdel-Aziz says that in his case Sulaiman was “surprised” and not too pleased when he decided definitely to establish his own operation. “He liked it to continue as it was,” Abdel-Rahman recalled.

When kind words of advice failed, the elder Rajhis tried to persuade the Ministry of Commerce, which until recently had the job of supervising Saudi money exchangers, not to grant the younger members of the family licences which would incorporate the name Al Rajhi. Despite the family's prestige and good connections, Salih and Sulaiman failed. The Ministry has always supported competition, and government policy in the mid-1970s, and since, was strongly in favour of encouraging entrepreneurs.

At dawn he would pray...

hand the gold on trust to a passenger...

and it always got to his brother in Riyadh.

After the end of a very embarrassing episode Abdel-Rahman bin Abdel-Aziz and Abdel-Rahman bin Salih began to rebuild reasonably good relations with the senior members of the family. Abdel-Rahman bin Abdel-Aziz says that he is still very grateful for the upbringing Sulaiman gave him. The other Abdel-Rahman (Salih’s son) gradually won the respect of his elders through running a thoroughly professional, conservative operation, in the footsteps of the original Rajhi companies.

Abdullah bin Salih, however, was not reconciled with his elders. From the beginning, he showed himself to be an impulsive trader who jumped into transactions. In 1978 the senior al-Rajhis told members of the royal family that they were sure there were problems in the youth’s business. They also advised the British travellers' cheque company, Thomas Cook, not to deal with the establishment. Two years later, in the summer of 1980, Salih and Sulaiman felt forced to put advertisements in several Saudi newspapers to declare that the Al Rajhi Company for Currency Exchange and Commerce — the main al-Rajhi concern — had no connection or relationship whatever with any other entity carrying the Al Rajhi name.

By the time these advertisements appeared the older al-Rajhis' businesses has been consolidated by a grand merger. In 1978, on Sulaiman's initiative, he and Salih had at last formally amalgamated their businesses and had persuaded two of their brothers, Abdullah and Mohammad, to join the. Both men had worked for Salih in the 1940s and 1950s, but both had later broken away, quite amicable, to establish businesses of their own in Riyadh — Mohammad in exchange, Abdullah in building materials. Copying the example set by Salih and Sulaiman, the four brothers had always worked closely together.

In the wake of the separations of the mid-1970s it seemed to the elder al-Rajhis that there would be much to be said for their consolidating what al-Rajhi businesses they could, simply because it would reduce the confusion in the minds of the public and give the main Salih/Sulaiman operation a stronger identity. They even made a final offer of reconciliation to the younger members of the family. But it was spurned.

The firm that came out of the 1978 merger was the Al Rajhi Company for Currency Exchange and Commerce, a general partnership which for practical purposes is directed by Sulaiman. The company is based in Riyadh, where Sulaiman has lived since it was founded.

The merger was completed when the traditional Saudi exchanging system was about to undergo its biggest upheaval yet, an upheaval that was to present Sulaiman with some of his most difficult decisions.

The sudden upward push in the general level of wealth in Saudi Arabia created by the 1970s oil boom put traditional Saudi values under pressure. Saudis — particularly those who, like the al-Rajhis, came from the Nejd — lived in an environment practically free of crime, based on mutual trust and respect.

Sulaiman believes strongly that those values should be retained. And he devotes a major part of his life to bringing up his 26 children strictly, modestly and in the fear of God. He makes a point of knowing where all his 100-odd sons, daughters, nephews and nieces are at any time. He records his advice on cassette and sends it to them wherever they are. They must remember to pray, not to drink, or consort with loose women, or overindulge themselves; they must work hard and behave in a quiet, dignified manner.

Without fail, Sulaiman himself prays five times a day, and ensures that those who are with him pray too. When he is in his office, he acts as Imam: he leads his staff in prayer. When he is in an aircraft he turns towards Mecca and prays during the flight.

The Quran sys that a man need not pray while he is travelling — he can make up his prayers in more leisurely circumstances — but the strictest Muslims do not take advantage of this dispensation.

He records his advice on a cassette and sends it to his sons, daughters, nephews and neices, wherever they are.

Sulaiman has all the outward signs of piety. His beard is full and his moustache is clipped, and he wears his thobe, the long white shirt, an inch or more shorter than most other Saudis: a further sign of piety.

Sulaiman al-Rajhi is distinguished from the most austere and puritan people of the Nejd mainly by the fact that he smiles. He has a twinkle in his eye and he is said by those who know him well to be a humorous and engaging conversationalist.

Like other very rich Arabians of the conservative school Sulaiman lives modestly. He has a comfortable, but not opulent, house. He refuses to buy a company aircraft: “Why should I have to fly always on one aeroplane,” he asked, “when I can fly anywhere I like by buying only a ticket, and have a choice of airlines?”

When Sulaiman established a chicken farm project in 1981 he explained his decision by saying “I am sick of seeing ‘Killed in the Halal way’ on fish.” In their rush to sell goods to the kingdom, food companies were claiming that they had slaughtered their animals in the religiously approved fashion. It is not necessary to kill fish in any special way, and companies which proclaimed their ignorance on this point left their customers wondering how much they knew about the Halal rules for chicken, beef or mutton.

What emerged from Sulaiman’s religious indignation was a company called al-Rajhi Sudais, which operates in the province of Qassim, north of Riyadh, and has a stock of a million chickens. It is the biggest chicken farm between central Europe and east Asia — perhaps in the world.

He believes in traditional values: thrift, honesty, the cohesion of the family and the good standing of its name. On an occasion when a major New York bank made a mistake, in failing to honour an al-Rajhi draft, Sulaiman felt that the reputation of his company had been questioned. He took the draft, boarded an aircraft immediately, flew to New York, went to the bank, forced it to admit its mistake, closed his account, and opened another at Chemical.

Sulaiman's nephew, who is learning English in Cambridge, was refused a credit card by a British bank. Sulaiman made this bank too aware of his displeasure at the slight to the family name.

The brothers give immense amounts to charities; how much is not known even by their most trusted employees. But when Salih was in a car accident last year, and was wrongly reported dead, impromptu memorial services for him were held in seven cities and towns across the kingdom.

Sulaiman has a fundamental belief in dealing directly with people. When he urgently needed to talk to one of his employees who was on business in Bahrain, Sulaiman told his aide: “There are 80 banks in Bahrain. He must be visiting one of them. Call eight banks; ask each of them to telephone 10 others. We will find him that way.” They did.

The breakaway by the younger members of the family was more than a personal blow to Sulaiman; it affected his ability to manoeuvre in the shake-up of the Saudi financial system which followed, and which is now at a crucial stage.

The brothers give immense amounts to charities; how much is not known even by their most trusted employees.

From the days when Sulaiman was shipping gold to Riyadh, courtesy of helpful airline passengers, the al-Rajhis have always held peoples' bank accounts.

They began to do this as a simple personal service to their clients. They would be asked to keep a bag of riyal notes or a suitcase of silver coins and they would do so. In the 1960s and 1970s the number of account holders steadily increased. As the habit of banking and the numbers of branch banks began to spread in Saudi Arabia, the ordinary, devout people of the Nejd decided that they would prefer to open an account with the Rajhis or some other exchanger rather than with the National Commercial or Riyad banks. They were aware that the payment and receipt of interest was condemned in the Quran as usury, and they knew that banks dealt in interest — even if they referred to it as “commission” or “fees of commitment”. They considered that, although they might refuse to take interest themselves, they would be morally at fault if their money helped the banks to earn interest.

The money exchangers, on the other hand, were known not to pay interest, and, apart from one or two possible minor cases, they did not take it. Even in their dealings with the commercial banks today, they do not accept or pay interest. They allow the banks to hold their balances interest free. In turn, the banks notify them if they become overdrawn. They then transfer sufficient funds into their account to cover the deficit, but they do not expect to be charged interest on the debit balance.

On the same principle, they periodically allow their own current account customers to overdraw, on the reasoning that the credit and debit balances will even out — or, more likely, show a substantial net credit in their favour.

One banker who has handled the money exchangers' accounts at one of the major Saudi banks for years points out that for the exchangers to deviate from these practices, and to be found out, would be utterly disastrous for their reputations. He had not come across a single case of an exchanger putting money with him and asking for interest — though he said that he had heard people mention cases of small dealers taking interest in London.

One of the major money exchangers recalls that he came into contact with interest only when he was asked by customers to arrange the placing of interest-bearing deposits in New York or London. When he did this he would charge a small commission or placement fee for the work.

Instead of earning interest with their customers’ funds, the conventional exchanges trade with the money. At all times they stay extremely liquid, but part is invested in real estate, shares, commodities and foreign exchange. It is foreign exchange dealing, on a vast and highly sophisticated scale, that has made the money exchangers rich. The profits from dealing in customers’ funds have been far bigger than the bread and butter income that the exchangers earn from selling drafts to the members of the foreign workforce in the kingdom, or to Saudis travelling abroad. The exchangers say that most of their foreign currency buying is done to cover the drafts that they issue, but they deal in sums much bigger than would be needed for this purpose.

As a result of their great popularity with ordinary Saudis and the profits they make on large quantities of interest-free funds, the money exchangers have become a major force in the Saudi banking system. The Al Rajhi Company for Currency Exchange and Commerce has one and a half times as many branches and as big a volume of deposits as the National Commercial Bank, the biggest conventional bank in the kingdom.

The unattractive feature of the money exchangers, from the point of view of the Finance Ministry, was that their activities were completely uncontrolled.

The money exchangers have the largest part of the small shopkeepers’ business, mainly because they stay open much later than the banks; shopkeepers deal with them at the end of the working day. Opening an account with a money exchanger is much easier and less bureaucratic than opening an account with a bank. The exchangers issue cheque books, in exactly the same way that the banks do, though the Saudi government does not recognize their cheques and government agencies will not accept them in payment.

The unattractive feature of the money exchangers, from the point of view of the Finance Ministry and the Saudi Arabian Monetary Agency at the beginning of the 1980s, was that their activities were completely uncontrolled. Members of the public dealing with or through money exchangers were, legally speaking, unprotected.

The exchangers could invest in whatever they liked. They were not required to maintain liquidity ratios or keep funds on deposit with SAMA, as the banks were obliged to do. When cheques drawn on accounts held with them were dishonoured, payees had no redress — because officially the government did not accept the documents as being cheques. When a cheque drawn on a proper bank account bounced, the law in Saudi Arabia was that the drawer automatically went to jail for three months, unless he could make arrangements with the payee for honouring the cheque.

A further objection — in official eyes — to the operations of the money exchangers as they stood was that they could affect the money supply, again without SAMA being able to do anything about it. In theory they had the potential to increase the money supply by making loans to customers within the kingdom, though in practice the size of their loans was small.

More significantly they could, and did, decrease it on a large scale by holding funds on the foreign exchange markets of Bahrain and London.

In early 1981 the Saudi government decided that the Ministry of Finance and National Economy should issue a set of comprehensive rules for the control of the money exchangers. These were published in December 1981. They referred back to a Council of Ministers resolution of 1974, which had never been given the force of law, and to the banking control law of 1966, which had categorically prohibited non-bankers from carrying out activities.

The new regulations were aimed at curbing the exchangers' activities. They stated that no further money exchanging licences would be issued, and stipulated that the existing exchangers should maintain certain levels of capital and liquidity.

In practice, SAMA has insisted that most of them hold in cash with banks specified by the central authority a sum equivalent to a fifth of their capital. As part of the new arrangements, the exchangers were placed under the authority of SAMA, rather than the Ministry of Commerce. The exchangers were instructed to provide SAMA with copies of their annual balance sheets, and SAMA was authorized to request monthly statements from the exchangers, together with any other information it needed.

The most important of all the new rules was one which stated that the exchangers should liquidate their current account and deposit-taking operations within three years, in accordance with timetables to be agreed with SAMA.

The money exchangers reacted to the new rules with as strong a protest as it is decent to make in Saudi Arabia.

Their instinctive reaction was summed up by Mohammad Mukairin, the son of Abdel-Aziz Sulaiman Mukairin and the manager of his family’s money exchanging office in Riyadh. “The purpose of the rules is not to control the money exchangers, it’s to drive them out of business,” he said some months after SAMA had begun to implement its controls. “There are other ways of controlling them if that is what the government wants.”

In due course, the money changers as a group produced a whole series of moral and practical arguments against the new regulations. They pointed out that theirs were the only totally Saudi financial institutions in the kingdom, apart from the National Commercial Bank; they excluded the other commercial banks from their category on the grounds that they were partly foreign owned, except for the Riyad Bank.

While they were making their complaints, the money exchangers were becoming horribly aware that one of their number was undermining their cause.

It was suggested that the money exchangers had emerged from Saudi society in response to a particular series of demands, that they fulfilled a need and that therefore they were a valuable natural development in a society where so many other forms of development were imported and imposed on society.

To support their protests some of the exchangers petitioned the King. Others went to members of the Ulema, the Saudi religious and legal establishment, and asked for their support — reminding them that exchangers ran their operations in accordance with Shariah law but that banks did not. What representations or informal comments the Ulema may have made on the exchangers’ behalf in meetings with the King or senior members of the royal family is not known; in fact the exchangers are reluctant to admit that they complained to the Ulema at all. Certainly none of the Ulema wrote articles in the press or delivered fatwas (legal opinions) on the subject.

While they were making their complaints and arguing for less draconian measures in the first six months of 1982, the money exchangers were becoming horribly aware that one of their number was undermining their cause. This was Abdullah Salih Rajhi, Sulaiman’s nephew, and the impulsive son of Salih al-Rajhi, who had broken away from his family’s main business in 1973 and had established his own money exchanging firm in Dammam. Over nine years he had opened more than 30 branches, most of them in the Eastern Province.

Abdullah Salih had invested heavily in silver and other commodities. When the price of silver collapsed he did not cut his losses but continued to chase them. And in 1982 he began to run out of funds to honour the drafts he had been selling to foreign workers in the kingdom.

On July 17, 1982 the Saudi authorities closed Abdullah’s establishment, froze his assets and put him under house arrest — where he has remained since. Immediately after the closure a committee was formed under SAMA to liquidate the business. It appointed accountants, Whinney Murray, to compute Abdullah's debts and assets.

That was expected by this summer. So far the people who have been hurt most acutely by the Abdullah Salih débâcle have been the immigrant workers who bought his drafts. Early in 1982 a Pakistani newspaper reported that drafts sold to workers in Saudi Arabia were not being paid when they were presented in Pakistan. The same happened in Thailand.

Within Saudi Arabia, the banks and the other exchange dealers seem to have escaped from the episode without loss. A senior manager in National Commercial said at the end of last year that his bank had known since the beginning of 1981 or earlier that Abdullah Salih had been in trouble.

The older al-Rajhis, the owners of the Al Rajhi Company for Currency Exchange and Commerce, had published their advertisement disclaiming all connection with Abdullah in the summer of 1980.

Several foreign institutions also discovered in time that Abdullah was in difficulties. Bank of America stopped the travellers’ cheque business it had with the exchanger six months before the closure, and American Express ceased dealing with Abdullah in November 1981 because it said he had “no business controls”.

A much larger number of foreign banks was caught with debts owing to them; some firms had already written off money owed by Abdullah in their accounts for 1981.

It is believed that some of the foreign banks confused the Abdullah Salih Al Rajhi Establishment with the Al Rajhi Company for Currency Exchange and Commerce. This may be untrue, but at the very least it seems that they believed that Abdullah had some working relationship with his father’s and uncles’ company. They did not realize how fundamental had been the split in the family or how early it had occurred.

The news was a terrible blow to the al-Rajhis. “To hear the older Rajhis talking of Abdullah Salih,” said a Saudi friend of the family, “you'd think that he wasn't related to them at all. You'd think he was a person far away from them who had done terrible things to them.”

The money exchangers had good cause to be upset. They lost a significant amount of business after the collapse of Abdullah Salih. In the austerely devout town of Buraidah in February this year a manager of a local bank noted that “the banks have been taking business back from Rajhi and the others — the bankruptcy of Abdullah Salih has been very influential in making people feel that the banks are more secure”. In the immediate aftermath of the collapse it is believed that Sulaiman, conservative that he is, kept SR2 billion in its offices in cash in case of a run.

Equally serious for the exchangers was that the Abdullah Salih affair weakened their position in their dialogue with SAMA over the central bank’s new regulations.

Officially SAMA maintains that the new regulations will be applied to all exchangers, but in a reply to written questions recently it added that “the question of whether new banking licences should be issued is a matter of broad policy for the Kingdom as a whole". This could betaken to imply the logically obvious point that if some of exchangers become banks they will outside regulations.

It is possible that a few of the very biggest exchangers may be allowed to become Islamic banks. Abdel-Rahman bin Abdel-Aziz Rajhi, the owner of the Al Rajhi Commercial Establishment for Exchange, says that he wrote to King Khaled in the late 1970s asking if he could be given a licence to turn his business into an Islamic bank. He envisaged a capital 0f SR200 million. The King referred the matter to SAMA, which is now talking to Abdel-Rahman about it.

As yet, the direction of Sulaiman's business is not known, even among some of his most trusted employees. But he has already provided some pointers.

In 1980 he established the Al Rajhi Company for Islamic Investments in London. This is a consultancy company which advises its parent in Riyadh on how it can deploy its foreign assets in a theologically acceptable fashion. “It leads Riyadh by the hand into situations,” its managing director, the highly able Elie El Hadj said, “but then it’s for them to decide whether to do the business, not us.” If the directors in Riyadh do decide to do business the transaction goes into the books of the Al Rajhi Company for Currency Exchange and Commerce.

Sulaiman, with Elie El Hadj’s advice, shunned leasing or real estate as his foreign investments, even though they are accepted as compatible with Islamic theology: for a trader, they were too long-term and would involve legal and tax complications. Instead, he opted to specialize in buying commodities for manufacturers — say ore on behalf of a steel mill — and accepting deferred payment at a fixed level of profit.

By the beginning of 1983 the Al Rajhi Company for Currency Exchange and Commerce was doing this type of business on a regular basis with 25 manufacturers that are household names in the industrialized world. They included four of world’s top 10 chemical companies, and several state owned corporations in OECD countries. In all, the company now has around $600 million of Islamic business outstanding, and it is building these very short-term assets quickly.

It had its problems at first. Said El Hadj: "It takes guts to call on the treasurer of a big company with an unheard of new idea — it’s much more difficult than just placing deposits with banks.”

So far no hint has been given of whether SAMA — and the King — will agree to Al Rajhi Company for Currency Exchange and Commerce becoming an Islamic bank. If they do, they will probably insist that the bank becomes a public company. Whether any of the other money exchangers will be allowed to become Islamic banks, or whether a new type of quasi-bank licence will be introduced, are even more open questions.

What is known, unofficially, is that the Al Rajhi Company for Currency Exchange and Commerce is temporarily exempted from having to dismantle its current account and deposit taking business by the end of 1984. The most plausible explanation for this seems to be that SAMA feels that there is no point in forcing the Rajhi brothers and their customers to change the way they do business until the Al Rajhi Company’s future has been decided.

Those close to Sulaiman believe he will turn his business into a bank, probably an Islamic one.

For a man who has turned very little into one of the world’s largest private fortunes, that would spell the end of the old, simple era, and the beginning of a new complicated age.