No one emerges with much credit from the deal that so nearly precipitated a global crash – the deal that nearly turned the clock back to October 1987.

The collapse of the $7.2 billion United Airlines buyout loan is a story of error upon error, of proud reputations suddenly tarnished. The UAL managers who put the buyout together were too greedy. The buyout consortium's investment banks, Salomon and Lazard Frères, trying to simplify the numbers produced overly optimistic financial projections for the company. The loan arrangers, Citibank and Chase Manhattan, were over-aggressive taking on a loan no one else would touch. They failed to sense that the mood of the market was swinging against leveraged deals. And they then completely mispriced the transaction when a few basis points of generosity might have saved the day.

It is also a story every borrower who has ever bullied his bankers into a finely priced deal should mark carefully. UAL's chief financial officer, John Pope, is such a man. And at some banks, the decision not to enter the loan appears to have been based partly on a desire for revenge.

One banker who knows Pope of old, says: “He's a pain in the neck. He's one of these people that likes to get a bank down on the ground and then put his foot on its throat. When you see a loan from him, you kinda start off with a negative attitude."

As the deal collapsed around them, the syndicators refused to recognise defeat and instead clung to the final, vain hope that Japanese banks would bail them out. When the Japanese didn't come through and news of the failure of the deal emerged, bankers in Tokyo found themselves charged with pushing world stock markets to the edge of collapse. The near catastrophe on Friday, October 13 and the following Monday widely blamed on their reluctance to support financing for the leveraged buyout of United Airlines.

The Japanese are not guilty. In fact, almost the only banks – other than arrangers Citibank and Chase – prepared to lend a bean to the buyout consortium were Japanese. The two US banks, grasping for commitments of $4.2 billion, never got more than $1.4 billion. Of that, $1.1 billion came from Japan and only $300 million from US and other banks. Far from being shot down in flames over Tokyo, as is still generally believed, the deal never got off the runway in New York. According to many bankers, it should never have emerged from the hangar at UAL headquarters in Illinois.

The $300-per-share offer for UAL was put together by a consortium comprising UAL senior managers, principally chief executive Stephen Wolf and chief financial officer Pope; employees, mainly the pilots, and British Airways. It was a speedy response to Marvin Davis, a raider who had propelled the company into play with an unwelcome $240-per-share offer, in August, later raised to $275 per share. In early September, Airline Acquisition Corp, the consortium's vehicle company, asked six money-centre banks to bid for the mandate to arrange $7.2 billion in senior bank debt to support the bid. The six were Bankers Trust, Chase Manhattan, Chemical Bank, Citibank, Manufacturers Hanover and JPMorgan.

The request was presented in an arrogant manner. A senior figure at one of those banks explains: "It was a fill-in-the-blanks request. The borrower already had its structure and wanted us to reply with a bid on the pricing. We got straight back to the borrower and told them to forget about the pricing, we could not possibly work with that structure. They simply replied that if we couldn’t, other banks could."

Lack of a mezzanine layer in the financing was an immediate objection among the bankers. But what really caught their eyes were the wildly optimistic forecasts for UAL's profits, on which the deal was predicated. "If you apply the remotest common sense, you must realise that what goes up also comes down," says the same senior banker. "These projections started from one very good year and just went up."

No wonder the banks did not like the projections. In 1988, UAL's operational earnings were $665 million, compared to $247 million in 1987 and $90 million in 1986. Net earnings were $1.1 billion in 1988, against $335 million in 1987 and $11.6 million in 1986.

Net earnings per share in 1988 were $38, against $6 in 1987 and 25 cents in 1986. A series of one-off events partly explain those extraordinarily strong 1988 figures. Net earnings were boosted $223 million by the sale of UAL's 50% stake in the Covia partnership. And UAL purchased 35.5 million shares of its own common stock at $80 per share, under a recapitalisation programme. But even rejigging the numbers to exclude the Covia gain and to take account of the reduction in number of shares, pro forma earnings per share from continuing operations still would have been $16.26. In other words, UAL performed at historic highs in 1988.

That was as nothing to how the company supposedly would perform over the next ten years. Net earnings were projected to be $1.3 billion in 1990, $1.5 billion in 1991, $2 billion in 1993, $3.15 billion in 1995 and $4 billion in 1999. The key assumptions underpinning these projections were that the load factor – the number of seats sold in each flight – should be stable at 66% to 67% and that the available seat miles, yield from ticket sales and passenger revenues should all steadily increase. Passenger revenues were slated at $9.7 billion in 1990, $11.4 billion in 1991, $15 billion in 1993, $17.7 billion in 1995 and $22.6 billion in 1999. Labour costs were calculated to decrease initially by $265 million and by increasing amounts thereafter, to reflect concessions from the pilots and certain other employees, which were part of the transaction. It was assumed that further aircraft purchases would be financed through leases. The consortium's fundamental economic projections were equally rosy and included a US inflation rate of 3.5% per year.

The forecasts were too optimistic for most banks: few bothered to devote time and money to crunch the numbers seriously. “The internal discussion at our bank was basically: 'What on earth are these guys trying to do?'" says one banker in New York. Airline industry analysts point out that the business they cover is a cyclical one and that airline stocks generally trade at lower-than-average price/earnings ratios to reflect that.

The company's shares closed at $164½ on August 4, 1989, the day before Marvin Davis announced his $240-per-share offer. The first quarter 1989 low was $106⅝. The company made a net loss of $48.7 million in 1985 on operating revenues of $5.3 billion.

Who put the projections together? Step forward Salomon Brothers and Lazard Frères. The two investment banks prepared the projections based upon information provided by UAL management and were retained by the purchaser to advise on the transaction and to assist in arranging the financing. In the frenzy that followed the collapse of the deal, their part appears to have been completely overlooked. So, too, was First Boston, which acted for the vendor and in a letter signed by managing director Robert Calhoun delivered its opinion to the UAL board that $300 per share was a fair offer.

"It's difficult to blame First Boston for recommending the highest available offer, but investment banks also ought to advise boards of directors as to whether transactions can be completed," says one LBO arranger at a rival Wall Street firm. "Since this deal came direct from fantasy island, whether it was 'fair' or not is a moot point." (No outsider knows what advice, if any, First Boston gave the vendors on whether the financing was practical, since the bank is declining to answer questions.)

The banks were right to be cautious. A source within one of the investment bank advisers reveals that, trying to simplify matters for the banks, analysts arrived at future revenue figures which were too optimistic. There was time pressure. The buyout consortium was feeling the heat from Marvin Davis, who, in early September was claiming that given access to non-public information, and if wage concessions could be negotiated with unions, he might be able to justify a bid higher than $300 per share. It was only on September 8 that Davis agreed to a standstill agreement. Even then he retained the right to bid for the company if it was to be sold at less than $300 per share or less than his own latest proposal.

The source agreed to tell his side of the story on condition that neither his own nor his company's name be mentioned.

"It was a tight schedule. The merger agreement was signed on September 14 and the tender offer was due to close on October 26," he says. "We based our projections in part on those First Boston [advisers to the vendor] had produced in conjunction with management. We didn't fully develop numbers on the operating efficiencies likely to accrue from United's new fleet." (United had commitments at the end of December 1988 to take delivery of 61 B737-300 aircraft, 15 B747-400) aircraft and 30 B757-200 aircraft in stages up to 1992.)

The source continues: "Instead we simplified things for the banks and had the yield figures [returns from ticket sales] growing perhaps more than we should have. Certainly some people doubted the predicted high levels.

"That over-optimism was balanced by caution on the operating efficiencies. The management honestly believes that the aggregate figures are sensible."

|

Armed with these figures, the buyout group approached potential lenders. The optimists at Airline Acquisition Corp were right about one thing: two banks did step up eagerly to the plate. On September 13, Citibank made an initial underwriting commitment of $2 billion and Chase came in for $1 billion. Jointly, the banks declared themselves highly confident that they could present the borrower with its full $7.2 billion within a month. The two banks did not construct the deal: Lazard, Salomon and the UAL management team can claim credit for that; Citibank and Chase simply chose to swallow their story.

Apparently oblivious to their peers' outright rejection of the deal, the arrangers rolled up their sleeves and prepared to syndicate it on overly aggressive terms. “They failed to pause for one moment and sniff the air," says one senior loan syndication specialist. “They did not realise that the climate was turning against leveraged deals."

The financing comprised a $6.4 billion six-month tender facility paying 1½% over Citibank base rate, proceeds to be used to purchase the shares of UAL Corp. This was to be repaid through a $7.2 billion permanent financing, the heart of the package, comprising a $5.9 billion term loan and a $1.3 billion revolving credit which would provide additional working capital. Margins on both elements were set at either 1% over Citibank base rate or 2% over Libor through their eight-year life.

These terms quickly drew unfavourable comparisons with the permanent bank financing of the RJR Acquisition Corp deal. That package, completed in February, included a six-year $5.25 billion term loan paying 1.5% over US prime or 2.5% over Libor. The upfront fees were also much richer on the RJR Nabisco buyout financing. While bankers could expect 1¼% for participating in the UAL deal at the $1 billion level, banks committing $1 billion on RJR took 3¼%. Providers of $500 million took 2½% in RJR, against only ¾% on UAL. In addition there were small incentive fees for banks making early commitments to the RJR deal.

The UAL arrangers' syndication strategy was not designed to win back friends who had been offended by the assumptions of the deal and its pricing. In many multi-billion dollar takeover financings, the mandated arrangers will first invite a small group of leading banks to underwrite the entire transaction. Then the loan will be offered to the whole market in a much wider syndication. The core underwriters' big-ticket commitments are eventually scaled back, according to the amount of debt sold down in that second phase of syndication.

Some banks tentatively considering commitments to the UAL financing claim that, when they contacted smaller banks to test the appetite for sub-participations, Citibank had been there first trying to offload its own $2 billion chunk. It became apparent that banks would be left to sell down their participations on their own.

Banks might have swallowed that problem had there not been so much else wrong with the deal. The lack of a mezzanine layer to protect banks, the fact that UAL's machinists, the workers who maintain aircraft, were hostile to the deal, the thin pricing, the absence of a sponsor of the buyout as KKR sponsored the RJR deal – all these factors counted against Citi and Chase. "We are a big UAL bank and we want to be loyal to the company," says one senior lending officer who refused to take up the invitation to participate. "But all the little marginal efforts – the little bit of give you need before you lend – just weren't there."

The reputation of UAL's John Pope as a hard bargainer didn’t help either, says this source. No one doubts Pope's brains, but he's regarded as an aggressive seeker of fine terms. "I've never met him," says the source, "but I know he's pushed the financial community around. Pope out-toughed himself on this one." This source takes a further pride in having rejected the deal, as if his action somehow recompensed for the gradual tightening of spreads on syndicated loans over the past decade. "Everybody finally stood up to be counted on this one," he says.

Not even UAL's closest banks supported the deal. Bank of America didn't sign up – and Richard Cooley, CEO of Bank America-owned Seattle First National Bank, is a director of UAL. Manufacturers Hanover turned the deal down flat, even though its chief executive, John McGillicuddy, sits on the UAL board. First Chicago, which has close ties with UAL, did not participate either.

The importance of Japanese banks to US highly leveraged transactions in general has been overstated since the collapse of the UAL deal. They rarely contribute more than 35% of the senior debt for such transactions. But they have some intriguing things to say on the UAL deal, to which they became more and more important as the syndication effort floundered in the United States.

The Japanese banks deny that they were leant on by the Ministry of Finance to boycott the deal or pull out of LBO lending, although they had been quietly reminded to keep a close eye on the percentage of their US exposure that is in LBOs. Of greater concern to them was a conflict between the UAL management and the machinists' union. The Japanese also were worried that the US authorities might unravel the transaction because of a proposed stake by British Airways.

Most pertinently, it seems that the Japanese found it difficult to get any explanations out of Citibank and Chase that would have eased their uncertainties. "Dealing with two US banks, they found it hard to get straight answers in Tokyo," says one source. One Wall Street LBO arranger thinks he has an explanation for this: "There was never a clear sponsor in this transaction, like KKR in RJR Nabisco. Clearly the management were calling a lot of the shots and the banks were playing a more pro-active role than usual in such deals. But it was never certain who was playing the leading role.”

Some Japanese bankers were concerned about the role of the pilots' union, presuming that to allow a union a say in management would lead to higher salaries and bad practices. That was a misunderstanding (the pilots agreed to wage cuts). Yet seemingly no one cleared up the misunderstanding.

Citibank and Chase Manhattan, ironically joint arrangers of the successful RJR deal, along with Bankers Trust and Manufacturers Hanover, must soon have realised that they had a pariah of a financing on their hands. They did not even bother to approach major money-centre banks which had declined to bid for mandate. An executive at one of those banks says: "They did not invite us in at first but towards the end, if they could have got a secretary here to admit she was interested in the transaction, they probably would have swarmed all over us."

Amazingly the arrangers never let on that the deal was struggling. One source involved inside the buyout consortium says: "In retrospect there were signs that enthusiasm for highly leveraged transactions was waning after the problems at Campeau Corp and turbulence in the junk bond market. But Citibank and Chase Manhattan maintained that they were highly confident. The UAL managers have been badly serviced by their bankers; they told them that the deal was as good as oversubscribed.”

It was only on the evening of Thursday, October 12, the closing date for the loan, that it began to dawn on the UAL management team that it was not going to get the financing. It seems that the arrangers had clung to the hope that the Japanese banks would passively swallow a loan their US counterparts had spat out.

Investors in UAL stock were massacred when the loan collapsed and the share price headed south. Ten days after the loan flopped, UAL hit $170. One of the unfortunates was Saul Steinberg, who retained a substantial stake in UAL through his insurance company, Reliance. One source close to Steinberg says: "Saul is as amazed as everyone else. He is one of the people to whom Citi said: ‘This is a done deal.' He is not a happy camper."

Why did Chase and Citibank take on a loan that no one else would touch? In their defence it should be noted that there was, at first, strong momentum behind the deal. Northwest Airlines (NWA) had recently completed a successful buyout, with its financing oversubscribed. UAL had the strong cachet of its link-up with British Airways and it had the support of the pilots' union. "Don’t forget that UAL is a terrific airline," says one banker in New York, "and that the market has swallowed other deals with poor structures in the past. It seems unduly harsh to say that the deal never stood a chance. Still, when you miss by the amount they missed by…”

In the days immediately following the collapse of the loan, the arrangers did little to redeem their reputations. On Monday, October 16, Citibank suggested that the financing still might be completed and even be oversubscribed and that a joint announcement with Chase was imminent. Bankers awaited the news that the deal had been rescued; it never came. Instead, Citibank's PR machine issued a vague statement to the effect that the arrangers were still talking to the borrower and potential lenders, although they had no agreement with either. It added that the arrangers had received expressions of interest from some potential lenders.

Expressions of interest? These banks had issued a "highly confident" letter to the buyout consortium. Calls to the arrangers were dumped unceremoniously to corporate communications departments which set new standards for non-communication. “Can you tell us what is happening with the UAL deal?” Euromoney asked Chase on Wednesday, October 18, as rumours flew that a revised financing was being touted. Chase's reply: "We have nothing to add to what we said yesterday. Negotiations are continuing.”

“We have received expressions of interest," contributed a spokeswoman at Citibank, "and there is no point talking to other banks. They are all bound by confidentiality agreements." The communications staff at UAL were equally unhelpful: "We are declining comment on any aspect of the financing."

Calls to Rodney Ballek, the Citibank division executive in charge of the deal, were not returned. But after maintaining a stony silence for 10 days, a source at one of the arranging banks defended the deal in a non-attributable interview. His argument was that the deal fell apart, not because of fundamental flaws in structure or pricing, but because of a litany of adverse events affecting the market's attitude to leveraged deals in general and airline financings in particular.

On September 15, two days after the banks were committed to the loan, Campeau's problems became public. “It has been overlooked," says the source, “that Sumitomo was a co-lead with Citibank on loans to Campeau. Japanese banks had a lot of exposure – problems with US LBOs weren’t just something they were reading about in the papers."

On September 25, the Department of Transport asked for a reduction in the stake held in NWA by the Dutch airline KLM, a move which raised doubts about British Airways' role in the UAL buyout. The next day, the department requested a great deal of information from UAL, “most of it pertaining to British Airways' stake in the proposed buyout” says the arranging-bank source. Concern and confusion over the US government's hostility to foreign ownership of US airlines dogged the deal, even though BA never intended to take more than a 15% stake in UAL. “Mr Skinner [Samuel Skinner, US Secretary for Transport] has not been helpful," says a senior figure at British Airways.

Also on September 26, Seaman Furniture, subject to a KKR-led buyout, requested concessions from bondholders. “Japanese investors had to make some write-offs," the source at the arranging bank says.

On September 29, the chairman and four other senior NWA executives resigned unexpectedly. The same day, Braniff filed for bankruptcy. On October 4, it was announced that the KLM stake in NWA would be reduced to 25%. On October 7, the machinists' union came out strongly against the UAL buyout and machinists at Boeing went on strike. On October 11, US Air reported lower-than-expected earnings. Finally: "We understand, and I accept that it is hard to confirm, that the Ministry of Finance, through one-on-one interviews with senior Japanese bankers, advised them to cool it on lending to US LBOs," says the source.

On the same day, Ramada announced that it was unable to raise financing for its LBO.

What the source omits to mention in his diary of woe is that several major financings were completed within 72 hours of the collapse of the UAL deal. These included the $11 billion Time-Warner deal, completed on unchanged pricing, as well as major financings for Container Corp and Beatrice Corp. These last two did require fine tuning on the terms and conditions.

"The facts are that the UAL deal was fairly conservative in its terms and collateral, compared to the successful NWA deal," the source insists. He points out that the NWA loan offered only ¼% over Libor more on its permanent financing and “because a large part of the UAL financing was a loan to an ESOP (employee share ownership plan) that would have been compensated for in tax advantages."

He points out that in other respects, participation and commitment fees mirrored the NWA deal, and adds: "Though the fleet value of NWA was higher, UAL had more in total assets. The pilots' concessions were a major linchpin. They were worth $50 a share. And there was an agreement to maintain UAL's competitive advantage, so that even if American Air [UAL's major rival] pilots took wage cuts, UAL pilots would still be paid 10% less."

The source insists that in the early days of the deal, syndicators at Chase and Citibank felt an oversubscription was on the cards.

"Some banks were falling over themselves to get into the deal. First Chicago were pushing hard for an agency role, but they didn't get it. I could read you 30 commitment letters, but that would give away who talked to you."

The source rang off, however, before he could answer another criticism. Why did the buyout consortium push through a deal with no mezzanine layer to provide comfort to senior lenders? "Having some form of mezzanine or stub paper would have helped," says one LBO arranger at a major New York boutique. "Certainly, from a bank's point of view, the deal would have done better to have some subordinated debt," says a loan syndication officer at one major bank which turned down the deal.

Wall Street LBO arrangers detect an element of commercial banking arrogance in this aspect of the UAL deal. They say that commercial bankers had been rubbing their hands in glee as the junk bond market lurched from one crisis to another this summer and were boasting that they would take over the financing of LBOs. An executive at Drexel Burnham Lambert says: "We are confident that we could have done a portion of this deal on a mezzanine basis. There is a perception that you cannot get junk deals done anymore: that perception is wrong."

|

UAL and Drexel had contact at various levels throughout the summer. Drexel's highly-rated airline analysts are known to be close to UAL, and Fred Joseph, CEO at Drexel, is known to have spoken to UAL chief executive Wolf during the buyout attempt, but nothing transpired. Instead the lead banks touted the absence of junk, with its high service costs, as a plus point for the loan. If they had succeeded, the rewards for the leading players in the deal would have been substantial. The managing agents, Chase and Citibank, shared a fee of $8 million for their initial commitment letter on top of the ½% commitment fee payable to all banks joining the loan. They also stood to share a $105 million fee for closing the loan. In its role as administrative agent, Citibank was to pick up some more loose change: $1 million on closing and $500,000 a year after that. And there would have been some rich men at UAL.

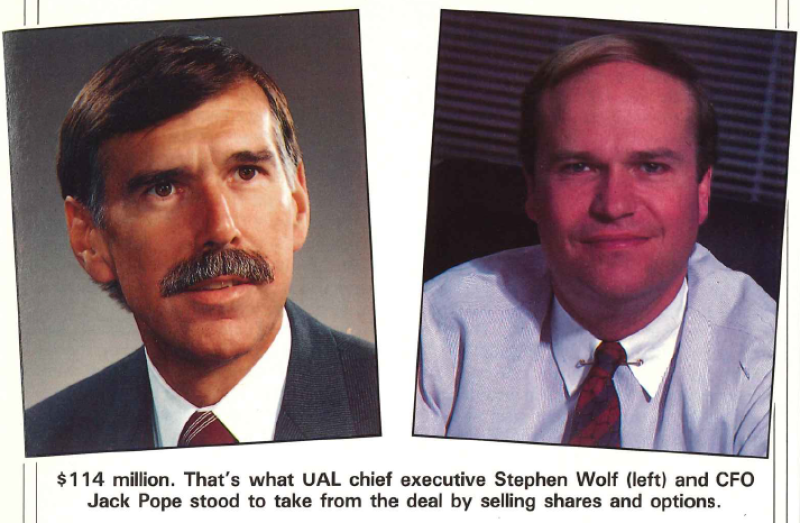

On September 8, 1989, Stephen Wolf beneficially owned 75,000 UAL shares and options to purchase 250,000 shares at an average exercise price of $83 per share. Pope held 10,000 shares and warrants to buy 150,000 more at $69 a share. If the $300-a-share offer had been completed, Wolf would have taken $22.5 million for his shares and $54.2 million for his options. Pope would have received $3 million for his shares and $34.6 million for his options.

The share structure of UAL after the buyout would have had senior management controlling 10% of the company. It was proposed that management investors initially purchase 1% of the new company for $15 million and that they be granted options to buy an additional 9% at $15 million per 1%. The machinists' union was enraged that Wolf and Pope should contemplate taking $114 million out of the deal for an initial investment of $15 million, while basing their projections on wage cuts.

Apparently the machinists were so angered that their president, John Peterpaul, got on the line to potential lenders in Tokyo to spell out the blue-collar union's discontent at the buyout. "If Wolf and Pope had been prepared to reinvest some more of their gains, that would have defused a lot of tension," says one Wall Street observer.

Salomon Brothers and Lazard Frères also stood to make a lot of money from the UAL deal. They were to be paid a ½% fee on the $6.8 billion purchase price of UAL. They would have shared $34 million, plus expenses. Alternatively, the purchaser further agreed to pay investment banking and legal fees of $26.7 million even if the buyout failed. Salomon Brothers Holding Co was paid $6 million for providing a commitment letter for $200 million in bridge financing.

Finally, First Boston was to take its cut from the vendor – ⅜% of the proceeds of the sale of the company. The fee to Morgan Stanley, British Airways' adviser, is not known.

The commercial banks fought hard to resurrect the financing for the deal because they had something more valuable than a few hundred million dollars in fees to salvage: their reputations.

Ten days after the collapse of the UAL financing, banks in Japan were receiving invitations to a re-worked loan on improved terms – from Citibank Chicago, not New York. Some were even considering acceptance.

Citibank has been the recognised leader of the syndicated loan market for as long as anyone can remember. Although nudged into second place in Euromoney’s loan arranger rankings for the first half of this year, the bank still heads all the polls of banks and borrowers as top house in loans. It regularly wins mandates for major LBO financings and was invited to arrange or co-arrange several multi-billion dollar deals this year. These included the $13.75 billion loan for RJR Acquisition Corp, the £2.35 billion financing for Newgateway and the $14 billion loan for Paramount Communications.

In reality, the arranging banks spent the week after the collapse of the UAL loan trying to twist people's arms to support a phantom loan. "Chase and Citibank no longer have authority to do anything on behalf of the buyout consortium," said a senior source at one member of that consortium on Wednesday, October 18. "What’s going on is a massive damage-limitation exercise," said a banker in New York. “They want to be able to say: 'Even if the deal is off, we still managed to get the financing.'" British Airways executives, who had proclaimed participation in the buyout as "an important strategic step", could not be seen for the dust as they fled from the transaction. “Off the record, the deal is dead," one senior figure at BA said, just two days after the collapse of the loan.

Aside from the issue of whether or not senior lenders will continue to bankroll leveraged deals, the collapse of the UAL deal raises many prickly questions for those who make their living out of LBOs. It bristles, for example, with conflicts of interest. Walsh and Pope stood to make millions by negotiating a price for an airline that they were trying to buy as well as sell. And Citibank was agent both for Marvin Davis, who put the airline into play, and for the beleagured management who tried to beat off his unwelcome offer with the buyout.

What value now the highly confident letter, the advent of which contributed as much to the restructuring bonanza in corporate America in the 1980s as did the invention of junk bonds? "Highly confident" used to mean: "You’ve got your money on the table." Only one of dozens of LBO bankers contacted by Euromoney seemed to have mulled over this aspect of Citi and Chase's failure. "It has enormous implications for the highly confident letter," he says. "Boards of directors must ask: 'What does this really mean? What does it provide me?'" The glib answer is that vendors must be more critical of who issues such a letter. But as the same banker says: "If you cannot rely on Citibank, just who in the US can you rely on?"

What validity can stockholders set by financial intermediaries' evaluation of a company? One day UAL was worth $164 a share, then $300 a share, then – according to unconfirmed details of Citibank's hastily reworked syndication – $250 a share. It is easy enough to say that a company is worth what the market is willing to pay for it but in this case Chase, Citibank, Lazard and Salomon, some of the biggest names in the business, couldn’t seem to guess within a mile.

Finally, how could the collapse of one syndicated loan almost drag down the world's stock markets – just because Japanese banks supposedly did not support it, when, in truth, they were the only banks that did?

Meanwhile, for those managers contemplating the launching of leveraged buyout financings, there are some clear lessons:

• Take time to set out correct and credible projections for the company. The botched figures on the UAL deal gave the whole transaction a taint it never could lose.

• Don't overload the financing with senior debt. With a mezzanine strip, the deal might have been viable.

• Be generous, or, at least be flexible. Many bankers believe that if the borrower had given away another 1% up front, the deal might have succeeded. Citibank tried to rejig the fees and the margins only after the deal was already dead. If it had quietly reworked the terms after the wave of rejections, there might have been a different story.

• Make sure the market knows who is running the show. None of the investment banks or commercial banks were to take a long-term investment in the buyout and BA seemed to take a seat at the rear of the deal.

The players

|

Stephen M. Wolf, chief executive of United Airlines. Ex-chief executive of Tiger International. Before that CEO of Republic Airlines. A past master of turning around ailing airlines. When he became CEO of Republic Airlines in 1984 it had a negative net worth of $28 million. Two years later NWA paid $884 million for it. At Tiger he turned a net loss of $55 million in the first nine months of 1986 into a net profit of $45 million for the similar period of 1987.Ironically he came out against LBOs in May last year, when he told analysts: "I think an entity could take on debt and pay it off over time. But I think it would cripple the airline. Every dollar to pay off debt is another dollar that could be used to buy an airplane."

John C. Pope, chief financial officer at UAL, ex-CFO at American Airlines. Characterised as a tough customer by the banks. "Jack is a very impressive individual," says one of United's bankers, "and very charismatic. When he comes into a room he very much takes control." Pope has a reputation as the best financial innovator in the aircraft leasing business although some bankers say that this reputation is undeserved. But one commented: “The best brains in air finance have beaten a path to his door with their best ideas." And Pope is renowned for his aggressive negotiating style. "He's notorious for getting the finest terms he can," says a New York-based air finance specialist. He and Wolf stood to take out over $100 million on the sale of UAL shares and options. "If they had been prepared to re-invest more of that money, it would have defused a lot of tension surrounding the buyout," says one Wall Street LBO expert.

Gordon Burns, MD in charge of the deal at Salomon Brothers, adviser to the buyout consortium and Eugene Keilin, top man on airline deals at Lazard Frères. Keilin has been quoted as saying that he was confident the banks could raise the loan and was impressed by the enthusiasm evidenced by their unusually large commitments ($2 billion from Citibank and $1 billion from Chase).

The structure

The ownership of United Airlines after the buyout was to be allocated 10% to senior management investors, 15% to British Airways and 75% to employees, via one or more employee share ownership plans (ESOPs). The vehicle company for the deal was Airline Acquisition Corp. Stephen Wolf, John Pope and other senior managers were to invest $15 million in return for 1% of the purchasing company's voting common stock and options to buy 9% more at $15 million per 1%. BA was to spend $750 million on preferred stock of the purchaser.

Of this, $250 million was to be in convertible preferred, which would have given BA control over of the purchaser's common stock. A further $200 million was to have been paid by BA for preferred stock paying 13% dividends, and $300 million for preferred stock paying 18% a year. Salomon Brothers Holding Co also committed to make a $200 million bridge investment in preferred stock of the purchaser plus warrants for 4% of common shares. This was to be an interim financing to be taken out eventually by the airline pilots' pension fund.

The financial structure of the new company would have been as follows:

Senior debt: $7.2 billion

BA preferred stock: $750 million

Bridge financing of pilots' preferred: $200 million

Management investors: $15 million

Excess cash: $1.27 billion

Uses of funds would be:

Acquisition of UAL shares and cancellation of options: $6,785 billion

Existing debt repayment: $950 million

Transaction costs and prepaid interest: $400 million

Working capital: $1.3 billion

Convenient but innocent whipping boys

Japanese bankers are claiming that they have been the innocent but convenient whipping boys for the collapse of the United Airlines deal. "Another case of Japan-bashing," they say of the world-wide condemnation in the wake of the October 13 crash on Wall Street that the UAL fiasco triggered. They maintain the Western financial community and news media were wrong when stating that the Ministry of Finance indirectly pulled the plug on UAL by telling banks to steer clear of the transaction and future LBO deals.

"We were not told anything by the Ministry of Finance or the Bank of Japan nor did we get any on-going guidance from them," says Makata Ota, assistant general manager at the international credit division of Sanwa Bank (which refused to commit to the deal). "It's natural for the banking authorities to point out, as they have, that LBO transactions are very speculative and risky and that they require specialist know-how to analyse the risks. But our decision not to participate in the UAL deal was based purely on commercial factors: we have an internal review body for LBO deals that considers them on a case-by-case basis and UAL did not fulfil the qualifications this body requires to take the risks."

|

The reasons he gives for non-participation are shared almost unanimously by the other Japanese banks that stayed away and those that pulled out following an initial commitment. Four Japanese banks – Mitsubishi Trust and Banking, IBJ, Dai-Ichi Kangyo Bank and Fuji Bank – committed around $1.1 billion to the loan, far more than the US banks. “The reluctance of US banks close to UAL – including Manufacturers Hanover, Bank of America, Morgan Guaranty and First Chicago – to participate emphasises the poor quality of the deal," says Ota.

Opposition to the deal on the part of the machinists' union was a major factor behind Sanwa's decision to stay away. “There was severe internal division caused by the union," says Ota, “and this concerned us greatly.” He adds: “Airlines are not suitable for LBOs. Not only is there fierce competition between them in the US but it is still a tightly regulated industry. These regulations can change from time to time causing great volatility. We were particularly concerned by the possibility of new regulatory controls against foreign investment which threatened British Airways' participation.”

A spokesman for Sumitomo Bank says: "We were put off by the amount of borrowing that UAL was scheduled to do in the future. We heard it intended to raise $20 billion in the next seven years and we thought this to be excessive. Also, the only assets UAL has to sell off to repay its debt are aircraft and the aircraft market is highly volatile."

There is one lone dissenting voice. Mitsubishi Trust, which remained committed to the loan after other banks pulled out, refuses to condemn the deal. But that seems to have more to do with the bank's links to British Airways than anything else. "We have had good and close relations with British Airways for a long time [the bank is stock transfer agent for BA in Tokyo] and were confident the deal would be a success, when they expressed very keen wishes to invest in UAL," says a Mitsubishi spokesman. "Also UAL's major assets, being its fleet of aircraft and the goodwill it has in the form of the air routes it has access to, were strong." He also plays down the problems with the machinists' union.

However, BA's exit from the deal changed Mitsubishi Trust's tune completely. “We think BA has no intention of trying again," says the spokesman. "And we would not participate in any new deal unless the US government were to give strong indications that it would not seek to restrict foreign ownership of US airlines. And, of course, the labour relations at UAL would have to improve."

The Japanese banks are loath to blame Citicorp for the deal's collapse. "The structure of the deal was not unacceptable," says Ota of Sanwa. "There was no mezzanine layer between the senior debt and equity in the Northwest deal and we participated in that successfully. It would not be unimaginable for us to participate in a similar structure again." Rumours that Citi and Chase were trying to sell-on their commitment to regional banks in their own backyard prior to general syndication were also discounted: "It was possible that they were trying to sell-on to the smaller regional banks," says the Mitsubishi spokesman. 'But that sort of strategy is very ordinary behaviour and not surprising in this sort of deal."

Tony Shale