The country has been eroded from within by corruption, threatened from outside by sporadic invasions from foreign-backed rebels and impoverished by the world slump in the copper price. But President Mobutu has used a vital card to trump any Western attempts to persuade him to put his house in order: Western fears of a communist take-over in a country strategically crucial in Africa and home of vital mineral deposits. There has been plenty of talking about the Zaire problem, and plenty of promises from Mobutu, but little progress. Arrears are some $900 million on total external debt of $3 billion.

The long-standing Citibank plan for a new international bank loan in return for payment of some arrears on commercial debt seems to have collapsed, and the task of ramming some economic sense into the Mobutu regime has fallen to a retired German banker, Erwin Blumenthal. As the IMF man in Zaire's central bank, he is attempting to staunch the outflow of valuable foreign exchange from Zaire at source, restore some order to the country's battered finances and so help the commercial banks to retrieve the money they couldn't retrieve themselves. Charles Meynell reports from Kinshasa; Simon Proctor from Europe; and David Lascelles of the Financial Times from New York.

IN ADDITION |

|

Erwin Blumenthal makes an unlikely candidate for the role of hero. He is a bespectacled 67-year-old German, who has spent most of his life in the Bundesbank, where he rose to be head of the foreign department. On his retirement he became consultant to the European-American Bank in New York, and then to the International Monetary Fund.

Now he may well become a hero of the international financial community. He is the man who has taken on one of Africa's most ruthless dictators, President Mobutu of Zaire, and one of the most intractable of all the less developed countries' debt problems. On Blumenthal's shoulders rests the burden of injecting some order into the financial chaos that has reigned for the past three years in a country riddled with corruption. Blumenthal is the last hope of the western governments and banks which have been paid hardly any of the principal due on their loans to Zaire since 1975. As the IMF man in Zaire, Blumenthal is now effectively running the central bank of that vast, uncoordinated central African nation. Until he arrived in Kinshasa on August 14, 1978, attempts to persuade the Mobutu regime to meet its international obligations had proved a dismal failure. The Citibank-inspired initiative to prevent commercial banks calling a default a default, and to induce them to talk about rescheduling without calling it rescheduling, had got nowhere.

Until the IMF, at the end of 1977, cajoled Mobutu into accepting IMF direction of the economy, attention had been focused on the rescue plan, masterminded by the senior vice-president of Citibank, Irving Friedman. The crucial element of the plan was the special account with the Bank for International Settlements in Basle, into which Zaire was to pay arrears on its repayments of principal on its commercial debt. When it had accumulated $130 million, Citibank would arrange a new $250 million Eurocredit on a best efforts basis.

Astonishingly, far from reaching the BIS account target, Zaire in August began dipping into the account in Basle with a withdrawal of $18 million. Consternation among the international banks quickly turned to despair, as at the end of 1978 the Banque du Zaire's Bofossa told Citibank that further talks on restructuring the country's commercial loans were impossible before the spring.

Blumenthal is having to grapple with powerful vested interests. Against him are ranged not only Mobutu, but a large number of his relatives and a host of influential businessmen, all of whom have so much to lose by the reintroduction of order into Zaire's finances that they might threaten Mobutu himself if the pace of reform promoted by Blumenthal is too rapid.

The IMF man is aware of these dangers. He sits behind a pile of folders puffing on a cigar in his office in the Banque du Zaire, where he is principal director. There is a sign on the wall behind him proclaiming - pointedly, in the Zairean context – “Serve others, not yourself”. He acknowledged: "There are special connections between groups with political muscle. They present a major obstacle to achieving economic revival, but we are working to abolish the influence of these groups, which only think of their own pockets."

Typical of the expenditure that Zaire can ill afford was the purchase by Citoyen Lito, Mobutu's uncle-in-law, of a Hercules C-130 aircraft. In September 1978, $13 million of the country's scanty foreign exchange was spent on a commercial version of this military aircraft. Visitors to Kinshasa airport at the beginning of December saw it sitting on the tarmac, gleaming white and brand new from the Lockheed works. Europeans living in Kinshasa were in no doubt that Lito would soon recoup the outlay on the plane from his diverse and highly lucrative exporting activities.

But the purchase of the Hercules may prove to be Lito's last extravagance. On November 29, about the same time that the plane was delivered, Erwin Blumenthal dropped a bombshell which reverberated throughout the ruling clique. He issued a directive forbidding all commercial banks in Zaire from doing further business with around 50 companies, including those belonging to Lito, to two members of parliament, and to other political figures. All the subsidiaries of the companies were included in the directive which also disallowed any further foreign exchange allocation by the Banque du Zaire to those companies. The ban on banking business is to be lifted only when the companies have repaid outstanding overdrafts, and even then it is not certain.

Whether Blumenthal will be allowed to continue to wage his one-man war on corruption in Zaire depends on Mobutu and his entourage. In the first battle with Lito, Mobutu apparently sided with Blumenthal. Shortly after Blumenthal arrived in Zaire, it is said he refused Lito foreign exchange for foodstuffs he wanted to import for his large wholesale and distribution company, the Société Générale Alimentaire. Lito's position in the republic had been almost untouchable till then, and he angrily complained to Mobutu. The president telephoned Blumenthal to say that Lito should be given the foreign exchange. Blumenthal is reported to have said that he would comply, but that he would be on the next flight out of the country. Mobutu apparently caved in. (Blumenthal refused to comment on this story.)

These are only the opening skirmishes in a war which will be long and bitter. Blumenthal will have to be firm but diplomatic. The very fact that he is there, and that another foreigner is taking charge of the budget and public spending in the finance ministry, is an implicit admission by the Mobutu regime that Zaireans are incapable of running their own economy. The whole situation could be interpreted in Zaire and Africa at large as an overt form of neo-colonialism and sensitivities must have been jarred by it in Zaire.

It takes a brave European to cross swords with the Zairean elite on their own ground. What happened to a Dutchman called De Wit who was working on a World Bank mission at the Banque du Zaire last year cannot be far from Blumenthal's thoughts. De Wit had apparently upset someone of influence through his work at the bank. One evening a 40-strong gang of soldiers burst into his home, raped his two little girls and made off with some of his possessions.

Blumenthal has considerably more scope for squeezing powerful Zairoise than De Wit had. Blumenthal is responsible for all monetary and foreign exchange policy, and for bank inspection. He has authority to take decisions independently of the Banque de Zaire governor, Bofossa. In his affable way, he takes a very firm line. "We have to force the commercial banks to follow the rules now. We have got to establish law and order in the whole system."

Perhaps Blumenthal's most significant monetary measure was introduced two weeks after his arrival in Zaire. This was circulaire 156 of September 1, which is designed to channel all available foreign exchange to the Banque du Zaire and to prevent further leakage of foreign exchange abroad. Banks cannot now open a letter of credit unless they have the foreign exchange in their own hands. They cannot add to existing debt, and 30% of export receipts must be automatically sent to the Banque du Zaire. The remaining 70% has to be split according to a strict set of guidelines: 35% to raw materials, spare parts, etc, 33% to food and pharmaceuticals, 25% to invisibles, 2% to energy and 5% to others.

Blumenthal's objective "is to make sure that the Banque du Zaire gets the foreign exchange in." He added: "On the import side, we are also pressing the banks to watch very carefully that they do not favour big business." Blumenthal's progress so far is still tiny, beside the scale of the problems to be tackled. But it is progress, in a tale of almost unremitting retrogression going back at least to 1975.

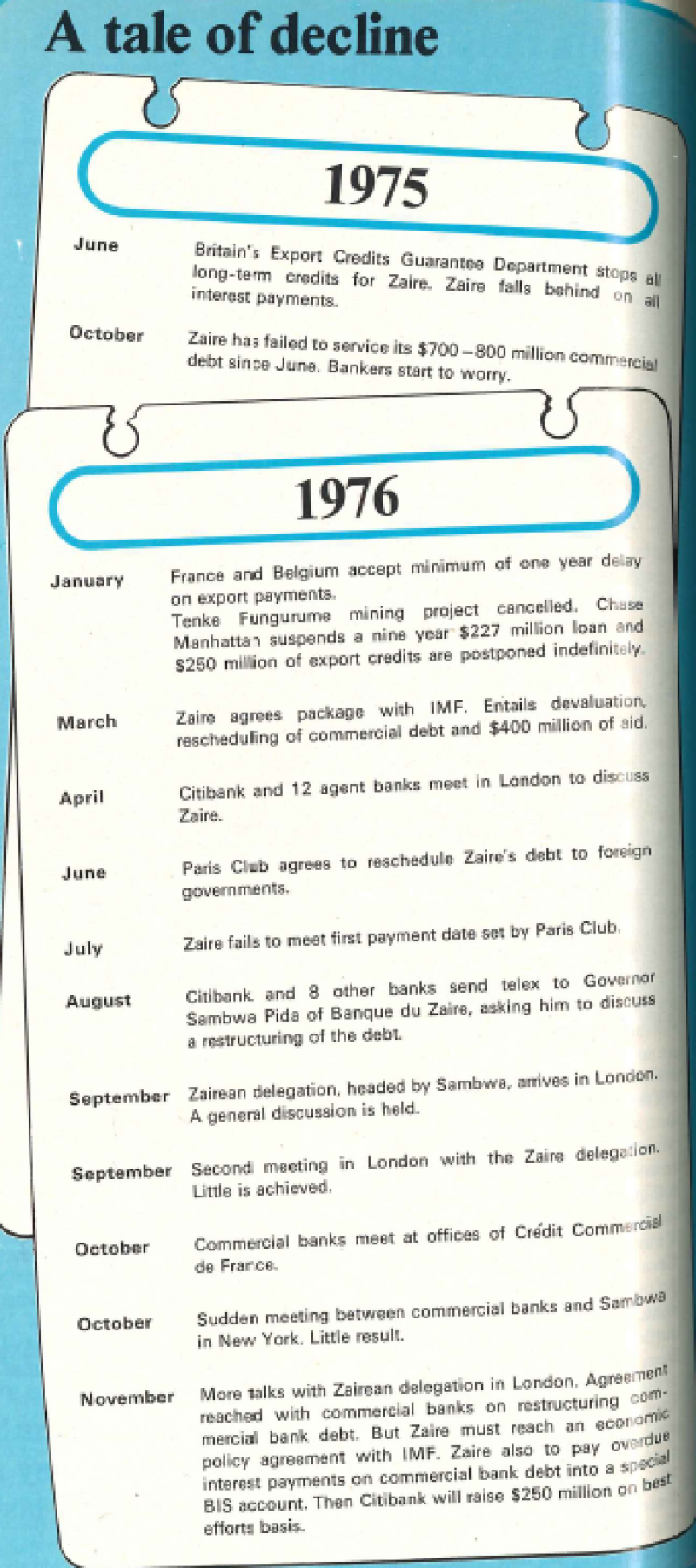

That was when Zaire first began to slip behind on payments to international banks. At the time there was general turmoil in the relations between the industrial countries and the less developed countries, and some LDCs began to talk seriously of a moratorium on their debts after the 1976 Unctad meeting in Nairobi. The banks were worried, though the amounts tied up in Zaire were not large. The direct bank exposure of about $400 million was divided between 120 banks, and Citibank, with the largest single exposure, had only $40 million at stake. Citibank's chairman, Walt Wriston, told Euromoney in July last year: "If we (Citibank) lost our total unguaranteed portion in Zaire, that would be a third of what we wrote off on the Penn Central. That's not a very exciting number, but people seem to get excited about it."

The excitement was about the effect of a precedent. If the banks failed to persuade Zaire against declaring a moratorium, there was the frightening prospect that Peru, Turkey, Pakistan and Sudan could do the same.

Citibank decided on an all-out effort to avert a moratorium. Its top management was called in to head the Zaire working party. It included Al Constanzo the vice-chairman, and Irving Friedman, the senior vice-president and ex-IMF/World Bank man.

The Citibank plan was developed around the principle of "restructuring" the debt, so that rescheduling could be avoided.

But, after three years of tortuous negotiations, Citibank has achieved almost nothing. Its much vaunted operation to safeguard the interests of the commercial banks has got nowhere and since August 1978, when Zaire drew $18 million from its account with the Bank for International Settlements in Basle, it has been virtually dead. In retrospect, this is not surprising. Zaire's capacity for meeting its obligations was minimal. It had been further reduced by rapid changes in the prices of some of its key exports and imports, and by internal wastage through economic mismanagement and corruption. Western companies and banks have been dazzled by the country's mineral wealth, without stopping to ask whether the Mobutu regime was capable of harnessing that wealth in a productive way. One banker wryly commented: "Zaire is a country with enormous potential, and it'll still be a country with enormous potential in 100 years' time."

Copper

Even after Zaire started to get into trouble with its debt, bankers pinned their hopes on copper. A crucial assumption behind the Citicorp rescue operation was that the world copper price would recover. But as another banker pointed out: "They were just guessing and they were wrong."

Dependent on copper for 45% of its foreign exchange revenue, Zaire saw the world price plummet by 130% in 1974. Oil and grain prices rocketed around the same time. The Benguela railway, which carried 45% of the vital mineral exports of Shaba province to the Angolan port of Benguela, was put out of action in 1975 by the Angolan civil war. The cutting of the rail link also put paid to Zaire's key copper and cobalt mining project at Tenke Fungurume in January 1976. Now the important supply of oil from Iran has suddenly stopped.

By 1977, the budget deficit was equivalent to a massive 12% of gross domestic product; by 1978 debt servicing was eating up an even more massive 50% of export earnings.

These statistics mean that the bulk of Zaire's population lives a hand-to-mouth existence. Once the plains of Bas Zaire, Haut Zaire and Kivu provided the country with enough coffee, cotton, tea, rubber and other crops to earn more than 60% of Zaire's export revenue. Now the US has to send emergency shipments of rice and wheat, while, for the elite, $5 million worth of luxury foods are flown in each month from South Africa.

The grim statistics also mean a farcical exchange rate. In mid-December 1978, the official rate of the zaire to the dollar was 1.03; to the pound 1.96. On the black market, the going rate was four zaires to the dollar, 10 to the pound. At the official rate, a ham and cheese sandwich cost $8; a four-day-old copy of the International Herald Tribune $7. At the black market rate, a room for a night at the Intercontinental Hotel (the only tolerable place to stay in Kinshasa) costs $14. The incentive to avoid the official rate is thus strong.

Perhaps most depressing of all is the question of how Zaire can recover when everything seems to be going into reverse. Gross domestic product was estimated last year to be contracting by about 5% a year. The mileage of usable road, 80,000 in 1962, has shrunk to only 12,000. The difficulty of obtaining spare parts has stopped most of the beaten-up old buses from running in Kinshasa, making it difficult for many Zairean workers to get to their work. Shortages of aviation fuel hinder most internal flights in a country which covers the second biggest area in Africa and in which a good domestic service is essential. Industry rarely runs at more than 30% capacity. Fishermen complain that even the river is against them, the current forcing the fish over to the Congo (Brazzaville) side of the river. And, at all levels matabiche (backhanders) are obligatory; corruption is entrenched.

Conditions had become so bad by last year that even Mobutu realized something had to be done. In February he took his foreign minister Umba Di Letete and central bank governor Bofossa to Brussels to talk with the Belgians.

The Zaireans agreed to have an IMF man nominated for number two position in the Banque du Zaire. The move was delayed by the second Shaba invasion in May, but this latest crisis at least had the effect of galvanizing both Western governments and the Mobutu regime into action. The Zairean regime published the Plan Mobutu in June in an attempt to assuage the populace and the country's foreign creditors. Hailed in the local press as the country's economic salvation, the plan was dismissed by a Belgian banker who has worked in Zaire for over 20 years as "just an inventory of the country's problems."

True, the three broad objectives outlined by the plan were glaringly obvious: the re-establishment of sound economic management; economic and financial stabilization; and an increase in agricultural, mining and manufacturing production and in transport services.

Golden opportunity

But for the Zaire Club of creditors it provided a golden opportunity to pin Mobutu down on specific detailed reforms. When the club – consisting of the US, West Germany, France, Britain, Belgium, Canada, Iran, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, the World Bank, the European Commission and the IMF, as well as Zaire – met in Brussels in June last year, it was agreed that priority should be given to streamlining the management at the Banque du Zaire and the Ministry of Finance. Within two months, Erwin Blumenthal had arrived at the bank in Kinshasa. Ismail Beatik, assistant to the under-secretary of finance in Turkey, is expected to arrive shortly at the Finance Ministry in Kinshasa to administer budget expenditures.

Zaire, said the Club, should also agree on a stabilization programme with the IMF as soon as possible in order to receive assistance from the Fund. The latest word from the IMF at the time of writing is that agreement might be possible by mid-March. At the end-of January, Governor Bofossa was due to meet the IMF and the Zaire Club in Washington. He was to bring a list of Zaire's economic targets, so that an agreement with the IMF could be brought one step nearer. But up to the last minute it was uncertain whether Bofossa would arrive.

Mobutu may be stalling because he expects resistance to the necessary belt-tightening from the elite on which he depends for his authority. In the past he has made only half-hearted attempts to clamp down on the flow of funds into the foreign bank accounts of his political colleagues. Mobutu himself can hardly be said to live frugally, with a personal fortune reckoned to run into many millions of dollars, and his own holding company to take care of wide-ranging business interests.

Mobutu also has one trump card which he has played again and again: the western fear of a communist take-over. Zaire's mineral wealth and its crucial strategic position in Africa have so far persuaded the western powers to support him through thick and thin.

From the point of view of countries like France, Germany and Belgium, these political and strategic considerations obviously outweigh the immediate concern over outstanding debt. If reforms instigated by Blumenthal or the IMF itself begin to erode Mobutu's political support, what will be the attitude of the western powers then? The US State Department, for one, says that non-cooperation by Mobutu with his foreign economic bailiffs could put an end to the longstanding US efforts to support him. André Ernemann, the Belgian ambassador to the UN who is chairman of the Zaire Club, regards the western pressure, through the IMF and the Zaire Club, as a test of the Zairean regime's will-power. Even though Belgium will not abdicate from its ex-colonial responsibilities, it is now ready to take a tough line.

At the November meeting of the Zaire Club in Brussels, Zaire asked the West to support a $550 million deficit as part of the stabilization plan. Having proved that this figure was based on inaccurate balance of trade calculations, the Club tentatively said that it might support a deficit of around $250 million.

But the real carrot from the Club is a three-year $1 billion investment programme (half of which will be financed with local currency). The World Bank was due to finish a detailed report on the programme before the planned Washington meeting, later than envisaged. "The investment programme may have been too slow," admitted Ernemann, "but it will largely be up to Zaire to make it work."

Despite all the problems and the conflicts of interests, Erwin Blumenthal is able to display both optimism and a sense of humour. But he was dead serious when he said: "I am convinced that Zaire could be really prosperous five years from now."

Whatever happened to the Friedman initiative?

|

| Irving Friedman |

What is the country's creditworthiness now? Have the attempts not to call a spade a spade for three years made any difference to Zaire in the long run? A Belgian banker said: "The Citibank loan was bad for the banks and bad for Zaire. It didn't do anything for Zaire. It just bought time – and only a little time at that. The Citibank loan was a solution for Citibank. It was not a solution for other banks." A British banker complained of arm-twisting by Citibank: "They more or less told us that, if we didn't go along with their scheme, we couldn't expect the arrears due to us to be given much priority."

Bankers acknowledge that Friedman had a broader approach to the problem – "less hard-nosed than the commercial bankers'" – but several questioned whether that was, in the end, appropriate. A London banker from an institution involved in the Citibank plan said: "With his World Bank/IMF background, he approached Zaire more from an aid point of view than from a commercial bank point of view."

To be fair, much of this criticism of the man who has been dubbed the Kissinger of the banking world (remember what happened to Vietnam?) has been made with hindsight. At the time, bankers and politicians in the industrial world were at one in their fear of the precedent that might be set by Zaire if it were to declare a moratorium on its debt.

When Zaire stopped most debt service payments in June 1975, nobody knew the precise figure for banking exposure there, except that it was around $600 million, and it was not until April 1976 that Citibank and 13 other agent banks met in London to discuss what could be done.

Two months later, in mid-June, the Paris Club (western governments which give aid) agreed to reschedule Zaire's government debt, only to find one month later that Zaire did not meet the first payment date. On September 2 the commercial banks had their first meeting with a Zairean delegation, headed by Sambwa Pida, then the governor of the central bank. By November 5, and three meetings later, an agreement was reached. Zaire must resume interest payments and pay off commercial bank debt arrears into a special account at the Bank for International Settlement and reach an agreement with the IMF. Then Citibank would raise a $250 million syndicated loan on a best efforts basis. A year later Citibank said that the loan was nearly complete. Zaire would have to find another $50 million (at most) and it could be signed. But it got no further. Zaire made no more regular payments and the Zairean economy went rapidly from bad to worse.

Worse still, as time dragged on without activation of the Citibank-led loan, the arrears piled up until they approached the $250 million that Zaire would get in new money. One source of delay was the loan agreement, which was extremely complicated. "Ordinarily, one would not lend to a borrower who was already in default," one participant in the operation said with some understatement. "So the loan agreement had to be worded so that whatever existed did not constitute default under the new loan at the moment it was made."

Rebel forces

Then, when the text of the loan agreement had at last been agreed by everyone involved and signing was imminent, rebel forces in May 1978 again invaded Shaba province, putting paid to completion of the loan. After that, the net influx of foreign exchange that would have been available to Zaire from the loan dwindled to almost nothing. A Paris banker explained: "There would be the effect of a restructuring, in that it would schedule payments over five years, but it would not really bring new financing into the country."

Many bankers now feel that the Citibank deal will never be consummated. One said: "I've been told unofficially that Citibank doesn't think it is any longer appropriate and that we need to look at other solutions. But Citibank doesn't want to take the lead because it would basically mean taking the lead in a restructuring effort. Citibank apparently wanted to be seen as the leader in the previous negotiations, for prestige reasons. With Citibank's change of heart, Friedman is no longer the key man on Zaire, even within Citibank. As one US banker put it: "He is more or less out of the picture now. The bank feels someone else in Citibank now has to look for a different solution."

But Citibank's Hamilton Meserve, who handles country risk assessment in Africa and the Middle East, insisted that there are no plans to back out of the proposed loan.

Friedman himself is still very much interested in Zaire. And, seated in his elegantly furnished office in Citibank's Park Avenue headquarters in Manhattan, he was far from pessimistic. Remarkably, he argued that the failure of the loan to materialize so far did not affect the broader picture. "The loan was conditional upon three things: one, that Zaire should get current on both interest and principal; two, that it had an agreement with the IMF for access to its higher credit tranches; and three, that there should be no further deterioration in its credit standing," he said. "So Zaire has taken the responsible view that since it can't yet meet these conditions, it doesn't want a credit that it cannot use."

Friedman added that no banks which came into the deal at the beginning have dropped out. And when any of them come to him and ask what they should do about the delay, he tells them: "just leave it alone."

He did admit, though, that Zaire's failure to top up the BIS account is an "adverse change", and that a situation could develop where arrears exceed the proposed new loan (now down to $218 million from $250 million, because only half the 120 creditor banks involved in Zaire felt confident enough to join). Other bankers have said that this leaves Zaire with little or no incentive to go ahead with the loan.

Meserve considered Zaire "set new ground rules" for relations between banks and LDCs: "It has shown that default is not seen as a viable strategy for an LDC."

Some bankers feel, however, that the situation is lost as soon as you allow a debtor country any leeway to catch up on arrears. A banker in Paris observed: "Any time you lengthen tenors, you reschedule. It is diminishing the present value of your original investment or loan."

Zaire has at least told the banks it recognizes its duty to keep them up to date on interest payments. This is crucial, because it means the banks do not have to write off the loans.

When arrears of principal will be paid is anyone's guess. On the commercial debt, they now amount to $215 million. There is little the banks can do except wait for the IMF to bring some improvement to the Zaire economy. An American banker summed up the dilemma for Citibank: "It can go to a country and say, 'Change your ways and repay your debt', but it's likely with politics the way they are that they will turn around and say, 'No, we will not change our ways and we will not repay our debt and not only that – we will nationalize your branch."

Ultimately, whether a debt gets repaid or not comes down to political will. Zaire is not as impoverished as some other Third World states; it does have valuable resources and sources of foreign exchange. Many people consider it could pay off its outstanding debts reasonably quickly if it wanted to. If it doesn't, there is nothing the banks can do about it. Friedman acknowledged the banks' ultimate impotence: "Banks cannot involve themselves in the decision-making process of a country. But the IMF can. The IMF can go into a situation which is not good enough for a bank." He added: "It should not be collecting our debts for us."

After three years of waiting some bankers will be glad to see the IMF control Zairean finances so that outstanding obligations will receive priority, rather than the "Mercedes and champagne" that one banker described as the Mobutu regime's main interests.