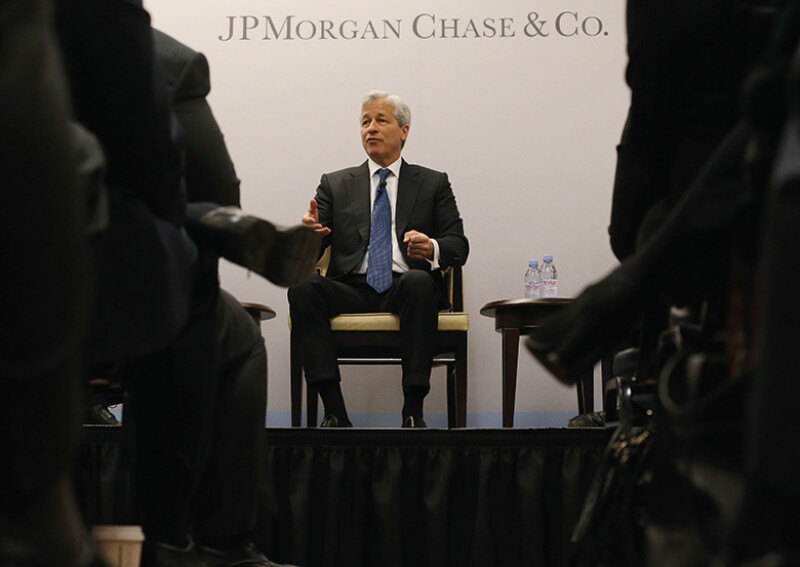

Jamie Dimon is the banker of his generation. The secret of his success? Be a great banker but be an even better businessman.

Has any individual ever dominated an industry as Jamie Dimon does banking today? The long-serving chief executive of JPMorgan Chase is often the loudest and most outspoken voice in finance. And people listen when he talks.

That might be because he has a rare mix of charisma and intelligence. But it’s mostly because he has earned the right to be listened to, having made JPMorgan Chase not just the most successful and powerful bank in the world but also one of the most successful global companies.

The Dimon/JPMorgan story has been told often, and many of the statistics that back up the tale are well known, but here is a brief summary.

The bank’s $32 billion dollars in profits in 2018 made it the second most profitable US-based company, behind only Apple but ahead of the likes of Alphabet – this, of course, in a highly challenged banking industry.

I was pretty tough back then. I’m not quite that tough any more. I was relentless with people

Those returns make it the most profitable bank in the world, if you set aside the peculiarities of the big Chinese state-owned banks. JPMorgan Chase is also the most valuable bank in the world, with a market capitalization of over $350 billion. Its nearest US challenger, Bank of America, is worth almost $100 billion less.

The bank is not just about size, it is also about quality. Take its investment bank. The firm has topped the global overall fee league tables each year for a decade. If you divide investment banking into the 24 sub-categories calculated by data provider Coalition, it was top in 16 of them last year and top three in seven of the others.

JPMorgan’s fortress balance sheet (how smart that strategy, begun when JPMorgan Chase merged with Bank One in 2004, looks now with hindsight) helped the bank survive the global financial crisis better than almost any other developed market bank. And since 2008, Dimon’s firm has truly outdistanced its competitors.

One chief executive at a competitor recently told Euromoney excitedly how the goal of a 13% to 15% return on equity was in sight, and how at that level a share price of two times tangible book would be the outcome. JPMorgan is already there, albeit its return on equity last year was even higher at 17%.

The Euromoney Bank Index shows that JPMorgan has outperformed the global banking industry benchmark by 210 percentage points since 2008.

What is the secret of JPMorgan’s success? Yes, the entity that is the bank today was created through the integration of a lot of stellar names in global financial services that gave it a great platform. But it is easy to forget that less than 15 years ago a lot of analysts, investors and competitors doubted the bank’s model would work. The concept of the fortress balance sheet was scorned at first as an excuse for delivering poorer returns than the more-leveraged market leaders.

In the end, it comes down to the fact that JPMorgan Chase is not just a phenomenally well-run bank, it is also a brilliantly run business. And a lot of that is down to Dimon.

Surgical approach

Dimon has banking blood in his veins; both his father and grandfather had careers in finance. He was studying and learning about the industry in high school. He seems to have innate instinct for what works – and what doesn’t – at a bank.

More than that, Dimon has a surgical approach to running a business, forged early in his career as a lieutenant to Sandy Weill, for whom he took on the role of CFO of Commercial Credit at the age of just 30 in 1986. There a young Dimon took a knife to unexplained spending and poor performance.

He was never afraid of getting his hands dirty, visiting warehouses and even clients who claimed they couldn’t pay back their loans to understand what the real situation was. His early access to senior people in banking and other industries at Weill’s side also formed his opinions on what makes people good leaders and what does not.

Even as he runs a huge global business active in every area of banking today, he manages to maintain that approach – which he distils down to “diligence and discipline” – and instil it in his management team, who are then responsible for transmitting it throughout the firm.

In his own words: “You have to know every asset, every liability, every person. You have to know your facts.”

“There are certain things you shouldn’t be surprised about: how do you do accruals, what are your real margins, what are you bullshitting yourself about? I was always a real fanatic about this.”

“ Most of us who have been around the block would rather have a well-run business even with a second-rate strategy, than a poorly run business with the most visionary and brilliant strategy.”

“Get the facts on the table. Share the facts. A balance sheet is not a hypothetical concept. How you treat people is not a hypothetical concept. Follow-up is not hypothetical.”

Coming together

The story of JPMorgan Chase, of course, is not just about Jamie Dimon. It’s a story of many banks coming together over the course of three decades to become a global leader.

When Chemical Bank merged with Manufacturers Hanover in 1991, each bank had a market capitalization of $1.5 billion. Today, less than 30 years later, JPMorgan Chase – the bank which they eventually became – has an enterprise value of more than 100 times the combination of the two.

On paper, most M&A deals look great, but they rarely turn out that way. When Chemical and Manny Hanny began those merger discussions, there was little sign that it would be the starting point for what followed. These were the two worst-performing big New York-based banks at the time. It was a merger born out of necessity.

Then came the Chase/Chemical merger in 1996 after a brief flirtation with Goldman Sachs by the latter, followed by JPMorgan in 2000, Bank One in 2004 and Bear Stearns and Washington Mutual in 2008.

Bill Gates said banks were dinosaurs. He was dead wrong

All of these were rare examples of successful integration. Why?

According to Bill Harrison, chief executive of Chase from 1999 and then JPMorgan Chase from 2000 to 2007, who grew up through the ranks of Chemical Bank, it was down to a playbook created by Chemical’s long-time leader Walter Shipley.

“Walter felt strongly about a culture of fairness,” says Harrison. “In a merger, the key was to pick the best people for the combined firm, whichever legacy business they came from. We always insisted on openness and transparency.

“We’d arrange an offsite with the top people from each side and get each to discuss what they liked and didn’t like about the other bank. Getting that side of things right early on made an enormous difference when it came to executing the tough decisions that any merger brings.”

Harrison first met Dimon as a client, when Dimon was a senior executive in Sandy Weill’s Travelers group. But they did not know each other that well personally before sitting down for an informal lunch at JPMorgan’s Park Avenue offices in the spring of 2003, when Dimon was chief executive of Bank One. The two men discussed various topics, including some of the speculation about industry consolidation. Towards the end of the lunch, they even casually played out what a hypothetical merger between JPMorgan Chase and Bank One would look like.

Bill Harrison and Jamie Dimon

“We both understood the value of mergers and could see the logic of combining JPMorgan Chase, which had a great corporate and investment bank and a decent retail footprint in the US, and Bank One, which had become a strong consumer bank under Jamie’s leadership and a top bank among middle-market corporate clients,” says Harrison. “But most mergers don’t happen because of disagreements over name, location and leadership rather than price or strategic fit.

“So we talked over lunch, and very quickly we agreed three things: the bank would be headquartered in New York; its name would be JPMorgan Chase; I would stay on for two years and then Jamie would be my successor. The last thing I said to Jamie was this would need to be a merger of equals financially. He rightly told me he could not comment on that because that was a question the board would need to answer.”

Harrison became chief executive of JPMorgan Chase at the age of 57. He knew he needed to develop a potential successor early on, but the bench at the firm at that time was limited. It so happened that even before the merger discussions, Harrison and the JPMorgan board had identified Dimon as one of the few external executives who could succeed him. Why?

“Jamie had already proven himself to be an extremely talented executive,” says Harrison. “His experience was fantastic – few bankers understood the full spectrum of banking, from consumer to wholesale, like he did. He also grasped the importance of the plumbing of a bank – accounting, finance, regulation and generally how operations work. He’d shown he could bring a bank together at Bank One, which had been through an ugly merger with First Chicago the year before he joined them. Jamie had changed the culture and maximized the value of the deal.”

There is no business we are in where I cannot point out someone else who is doing something better

It’s no wonder Harrison describes the day the JPMorgan/Bank One merger was announced as “the most satisfying day of my career. Some people say we paid $58 billion for Jamie. And while there is no doubt we got Jamie and his extraordinary leadership as part of the deal, the truth is we had created an unbelievably strategic merger.”

What does Harrison put Dimon’s continued success down to?

He echoes Euromoney’s thoughts: “First and foremost, Jamie is a great businessman who knows how to make the most of an organization. There are three leaders who stand out for me during my career: Jack Welch at GE, Larry Bossidy at Honeywell and Jamie. All of them are great operating guys.”

Staying 'scrappy'

Dimon has become much more than this. He is a truly public figure. His annual chairman’s letter gets longer and longer (it comes in at close to 50 pages for the 2018 annual report) and opines not just on the banking industry but also about issues close to his heart in the US economy and politics. Some peers think he has gone too far. But Dimon is not going to stop.

He has also positioned himself as a champion of the positive role that banking can play in society. It might be easy to say, as he does to Euromoney: “This whole primacy of shareholder value thing – I have never believed in it,” when your share price has outperformed your competitors for more than a decade.

But speak to Dimon about the work that JPMorgan has done investing in the regeneration of Detroit. He thinks it is the right thing to do. He’s at least as effusive about this as he is about JPMorgan topping all those league tables. He applies the same ruthless business logic to the positive outcomes the bank is looking to achieve: reviewing, analyzing, studying. He believes such initiatives have made JPMorgan Chase a better company.

Dimon’s biggest fear is complacency. He wants to stay “scrappy”, a favourite word.

But the company he has built faces a big challenge. Dimon is now 63. He won’t be at the bank for ever. One of his great achievements has been to create a defined, positive culture in a business that is actually rather new, made up of several different banks coming together over three decades. Does JPMorgan Chase really have the rather more established, and to those who work there vital, culture of say a Morgan Stanley or a Goldman Sachs?

Rivals say the problem JPMorgan faces is that its culture is wrapped up almost entirely in the image and brand of its leader. He’s the glue the holds it all together. He inspires an almost cultish devotion. Who can fill his shoes when he calls it a day?

Dimon addressed this and many other issues in an interview with Clive Horwood and Peter Lee in New York in May. The model of a modern banker, Dimon arrived in jeans and open collar. All of his fabled charm, intensity and blunt speaking were on display throughout.

The meeting took place at JPMorgan Chase’s temporary headquarters at 383 Madison Avenue, the former home of Bear Stearns. The bank’s traditional HQ, next door on Park Avenue, is being torn down and rebuilt to a sparkling design by Foster + Partners. Once complete, it will house nearly twice as many employees as the old building.

Ever the attention-to-detail man, Dimon has visited other renovated offices – including a tour of Citi’s executive floor in downtown New York with chief executive Mike Corbat – to learn more about how a modern bank building should look.

The rebuild will take five to seven years. By that time, Dimon might well have left the chief executive’s chair. There are rumours that the new building might be named in his honour.

It would be a fitting tribute. But Dimon’s true legacy will be whether or not he has built a bank that can continue to thrive after a transition away from his leadership.

He seems confident that it will: “I think the chance of the next CEO driving this firm in the same kind of direction is pretty high.”

Q&A

Euromoney Why did you choose a career in finance?

Jamie Dimon (JD) My grandfather was a Greek immigrant. He was very smart but didn’t finish high school. He gets here, goes to the Greek part of town, washes dishes, eventually becomes a banker and then a stockbroker. My father joined him, having graduated from Hofstra. I have two brothers. One went into physics, one into education.

But I was always interested in the business world. I read the books in high school: the big ones, like Graham and Dodd’s ‘Security Analysis’. The company my father worked for was Shearson Hamill & Co, which had been through a number of mergers. In college I wrote a paper on that merger and that got me more interested. It wasn’t banking per se, more financial services that interested me.

Euromoney What was your first job?

JD My mother sent that paper I wrote to Sandy Weill, and on the basis of that I got a summer job at Shearson basically doing budgets. They had never done branch budgets before. It was quite amazing. They had 40 to 50 branches, and I was going into them and putting together numbers for the financial controller. Peter Cohen was the CFO at the time.

Euromoney At what point did you think you might run a business like this?

JD Not early on. But financial services was a fascinating business. It’s such a critical function, moving capital around the world. That needs to be done not just by banks but also institutional investors, brokers, private equity, you name it.

I went and worked for two years at a consulting firm. And I realized I did not want to be a consultant. It was not a great firm but it was a great education: you got to see good companies and bad companies and learn how they worked.

Then I went to Harvard Business School and after that I took a job as Sandy Weill’s assistant. I had offers from Goldman Sachs, Lehman Brothers and Morgan Stanley, but I wanted to build something. I was fascinated by what Sandy had built. He had sold his company to American Express for $1 billion and he said: ‘Come here, I need help, this is a fascinating organization, I’m not sure how it will work out but you’ll learn a lot.’

You can have setbacks, but there are certain things you shouldn’t be surprised about

Euromoney What did you learn?

JD I got to see the inner workings of a large corporation for better and for worse. It was big, it was political, you saw a lot of bureaucracy and it was the first time I ever saw how the top managers operated. I had never met CEOs, CFOs or treasurers before. That was the first time I thought I could do one of those senior jobs one day. I wasn’t thinking CEO, more treasurer or VP of financial analysis, maybe CFO if I did really well.

I wasn’t striving to be a CEO. How can you possibly know what you want to do with your life or what you’re going to be good at when you have done so little?

Euromoney At a young age you were a numbers guy?

JD It was more than just the numbers. I went to the sales conferences, saw all the administrative issues, witnessed errors on the trading floors. I got a broad education about how companies work… or don’t work. And then when Sandy left, I left with him.

We found this crumby little company called Commercial Credit that was 100% owned by Control Data and found a way to take it public. It was just a platform. It was not a good company. It was in consumer finance. But it also had a hotel in Ireland from a default on a loan. It had a tiny little insurance company called Gulf Insurance. It had irrigation systems in kibbutzes in Israel.

Consumer finance was the good business. We set up a group to get rid of these other things and I was partially responsible for that too, managing the disposal of these assets around the world.

Euromoney What things did you learn then that still inform how you run a business today?

JD The diligence and the discipline. You have to know every asset, every liability, every person. You have to know your facts.

I remember there was a loan from a guy that refused to pay us. He owed us money on a deal that went bankrupt. He had this huge house. The guy had plenty of money. I had someone drive by the house and do a valuation. When that came back, I went to the guy and told him: ‘You’re going to pay us.’ When you work at a bad company you learn a lot about prioritizing what needs to be done and how to fix things.

Euromoney What else did you fix?

JD Well, there were the expenses: I learned how people that approve expenses often have no idea what they are approving. We used to have people move desks or offices around the building, and every time they moved the phone company would charge us $500 to move their phone with its number. We hired a part-time former phone company guy so that instead of paying $300,000 a year to the phone company, we were paying this guy $20,000 and he would come in once a week and move everybody’s phone.

We were paying $20,000 a month to water plants on the executive floor. There were no plants on the executive floor. People just kept on and on paying these bills even though the plants had gone. I could give you a million stories like that. They never leave you.

Some of the reports were being sent to a man in Dallas who had died three years earlier. So we stopped printing a ton of reports and I cut our printing cost by 50% to 60%

Euromoney It sounds like you took some enjoyment from all of this.

JD I remember one thing that made me very proud. We had to do all this printing every month and the cost was going up and up, and the staff wanted to buy a big new Xerox printer. I said: ‘No, let’s get our printing down.’ Six months later they had got it down by 8%. That was pathetic. I told everyone: ‘My grandmother could have got it down by 8%.’

I got copies of all the reports. I arranged a big conference room. I laid all the reports out. I had a list of everyone who got the reports and I had each one of them come in and said to them: ‘Tell me what’s in that report.’ Not many could answer. Some of the reports were being sent to a man in Dallas who had died three years earlier. So we stopped printing a ton of reports and I cut our printing cost by 50% to 60%. I sent one guy to look at our paper supply. We were paying a lot of money to store paper. But when he got to the store there was no paper there.

A year and a half later they came back and said we really do need to buy that printer. So I reluctantly spent $2 million for one. We were just in the process of buying Primerica. I’m down in the warehouses in Primerica, because meeting people on those kinds of trips is invaluable. I noticed this machine and said: ‘Hey, that’s a new Xerox printer. I just paid $2 million for one of those. How much did you get this for?’ And they said we got it out of the box for $50,000 from a company that went bankrupt.

So, you learn… often the hard way.

Euromoney How can you keep that attention for detail as you rise and run bigger companies?

JD Because you get a nose for it. You hire people with a nose to do it. I hired Charlie Scharf [now chief executive of BNY Mellon] who did that kind of thing with me. He was a killer that way. You have instincts. I do worry that, in a big company, people grow up without those kinds of instincts because so much is done for them. But you train people and we are diligent. This kind of work is not just sitting in an office reviewing paper. It’s getting into the warehouse, seeing what actually goes on.

I used to check people’s T&Es but I wasn’t really checking what they spent on travel and entertainment. I was checking how hard and smart they worked: how many meetings they had on a trip, what time they left and what time they came back. I’m a strong proponent of balance in life, but when people complained about headcount I would say: ‘I can prove to you that you’re not working very hard, so don’t complain to me about hiring restrictions.’

But that’s just one side. The other side of running a good business is you have to go and shake people’s hands, go to the sales conference, talk to them, understand their problems, sit at their tables, respond to them. And whenever you go on a trip like that, keep a list. What did you hear, what did you learn and what did you do about it? If our people are right about some problem, you fix it. If they’re wrong, you explain it. Have the decency to tell them: ‘We looked into it, but this is how it’s going to work.”

Always look at the competition. Always assess the landscape. Keep growing. There’s bad expense and good expense. Obviously, you want to spend efficiently. Good expense is that new branch, that new banker, that new piece of technology. It’s the easiest kind of expense to cut. But that’s the absolute worst thing you can do.

Euromoney Were you surprised to rise through the ranks as quickly as you did?

JD At Commercial Credit, I became the CFO in 1986 when I was 30. I just got more and more responsibilities. I picked up technology. By the time we bought Primerica, I oversaw most of corporate, HR, finance and risk functions. Not the big ones: they reported to Sandy. But then I became chief operating officer of Smith Barney. At the same time, I was president and chief operating officer of Primerica, so I just kept accumulating responsibilities. I knew I could run companies. I was already doing that. And I didn’t expect Sandy to go anywhere. I loved what I was doing.

Euromoney Who were the main influences on your career?

JD Well, my father for instilling certain values as well as how you should treat people. Bob Lipp [a former senior executive at Chemical Bank, Citi and Travelers] became a great partner of mine, as a friend, as a person and as a great manager. I just learned a tremendous amount from Bob. I learn a lot from watching other people, how they lead and how they analyze a problem and manage situations.

You also learn about people who, when there’s a problem, ask: ‘How can I help’. There are others who move as far away as they can from a problem lest they be tainted. I learned from Bill Harrison through the merger between Bank One and JPMorgan Chase. He’s a real gentleman. He shows you can be a very tough-minded person and still be a gentleman.

Left to right: Deryck Maughan, CEO of Salomon Brothers, Sandy Weill, CEO of the Travelers Group, Robert Denham, CEO of Salomon Inc, and Jamie Dimon, CEO of Smith Barney in 1997

Euromoney Although your working relationship ended in a difficult manner, do you still see Sandy Weill as a mentor?

JD I learned good things and bad things from Sandy. I am disciplined around facts, people, analytics, details, reporting, get back to me, follow up.

What he taught me was to get in the field, go to the sales meetings. It didn’t matter to him that he was CEO. CEOs of big companies don’t go to the sales meetings. But they should. You are assessing what you do. Being a CEO is not just the numbers. You are trying to assess your results, your performance. If your products suck, your services suck, your salesforce sucks or your attrition rate is too high, then your results aren’t going to be very good.

Euromoney Where did the concept of the fortress balance sheet come from?

JD I talked about it way back. Remember my dad was a stockbroker. In the recession in 1974, which is one of the worst we’d ever had until the global financial crisis in 2008, I saw the vicissitudes of markets. In ‘74, I remember the limousines were off the streets, restaurants being closed. And then the same thing in 1982. Inflation hit 12%, the 10-year bond yielded 14.75%.

People would say that can never happen again. And I would say: ‘You don’t know that.’ And I would make a list of all the calamities we had from Penn Central to Mutual Benefit, the failures and bankruptcies. Listen: these things happen. Some are predictable and some are not. You are going to have cycles. But you also can have financial services companies blowing up and you have to be prepared. So that was part of it.

Second, I used to tell people: on balance sheet or off balance sheet, netted or not netted, I don’t really care. Get the details, do the analysis, know the facts. What does it all mean? You can have setbacks, but there are certain things you shouldn’t be surprised about: how do you do accruals, what are your real margins, what are you bullshitting yourself about? I was always a real fanatic about this. For me, a fortress balance sheet is all about capital, liquidity and really understanding the company and being prepared.

It also means having sufficient diversity so that even if a portion of your earnings go down, you will still be fine.

Most of us who have been around the block would rather have a well-run business even with a second-rate strategy, than a poorly run business with the most visionary and brilliant strategy

Euromoney Have you ever doubted the diversified, universal model?

JD It is a real benefit in financial services. We are not a diversified conglomerate. All our businesses feed each other. There’ll be errors and problems, earnings may be up or down 10% one year to the next, but a lot of them are like annuity streams – cash management, asset management, many parts of consumer banking.

And then there are businesses where earnings are more volatile. That doesn’t mean they are bad. They are just more episodic: M&A, equity capital markets, certain trading results. But I’ve always agreed with Warren Buffett. I’d rather have a lumpy 20% return than a steady 12% return. If it’s a good business, I don’t care about weak results for 12 months. But parts of the investment banking business have very steady returns.

Now look at the regulations. CCAR [the Federal Reserve’s Comprehensive Capital Analysis and Review] kind of recognizes the benefits of diversification if you have good earnings and margins, although risk-weighted assets do not recognize it. But if you look back at the firms that blew up in the financial crisis, a lot of them were monolines: monoline insurance companies, monoline investment banks, monoline mortgage companies.

But there is also a danger in becoming too complex. One of my disagreements with Sandy about Citi was that we were too big and too complex in a number of totally unrelated businesses.

At Travelers, we were very successful: the stock went up 10 times, we bought businesses and ran them well. But what did Commercial Credit have to do with property and casualty insurance? When we merged with Citi, my instinct was to bring more focus to the business. Most people in the organization didn’t understand the particular risks of property and casualty insurance, of life insurance. Citi was big enough by then to focus on global consumer, global corporate, global asset management and those kinds of areas where you have huge synergies and diversification at the same time. Which is what we have at JPMorgan today.

Euromoney So you never believed in Weill’s vision of the financial supermarket?

JD They brought a truck leasing company for goodness’ sake! At JPMorgan Chase we are not a financial supermarket. There is nothing we do that does not also help other parts of the company. It’s the same at a successful small community bank: they will make you a commercial loan, have your checking account, maybe even do some asset management. That’s diversified. But his idea of the financial supermarket was to be in truck leasing, consumer finance, global investment banking, life insurance, property and casualty. I would not agree with something like that.

That looks like an accident waiting to happen. It was an accident waiting to happen.

Euromoney Are banks today as well run as companies in other industries?

JD If you can’t run a business well, you shouldn’t be in it. We are not complex because we want to be. We keep it as simple as possible, but we operate in complex markets. Most of us who have been around the block would rather have a well-run business even with a second-rate strategy, than a poorly run business with the most visionary and brilliant strategy.

There are so many ways in which companies can be poorly run. Some are too political. Some lack discipline altogether. Some get arrogant, they actually think they are the best in the world. Complacency is a killer. I remind our people constantly about the rebirth of competition: new challengers crop up in each business we are in.

Today you have fintech, Silicon Valley, e-commerce companies: they’re all coming for us.

Euromoney You’ve been the most successful bank for some time. How can you avoid complacency?

JD Because our meetings concentrate on what we do wrong. Bob Lipp always says: ‘Celebrate your successes, but in the management meeting emphasize the negatives.’ There is no business we are in where I cannot point out someone else who is doing something better: they’re doing digital better, they’re doing customer service better, they’ve got better customer-satisfaction ratings. And we are disciplined. We pound the table on it. We review, review, review. We expect people to criticize themselves.

But we all worry about the risk of complacency. We talk about it a lot, in every town hall. We always ask why weren’t we faster on this, why didn’t we do better on that. We sent a plane load of our people to China to see their leading companies. They came back motivated: a little scared, but motivated to do more and quicker.

Get the facts on the table. Share the facts. A balance sheet is not a hypothetical concept. How you treat people is not a hypothetical concept. Follow-up is not hypothetical

Euromoney Are you a little scared?

JD Yes, but I’ve always been that way. How many times have I been through it, seen companies blow up and terrible things happen or the competition eat your lunch. You’ve got Silicon Valley putting tens of billions a year into fintech and then you’ve got the big technology companies. They’re coming in some fashion. It may not be a frontal challenge, but they all want to be in payments, they all want to hold money.

Euromoney But they don’t want to be regulated as banks.

JD Maybe not – and that could be a protection. But our management team does not rely on that. Because you can white-label a bank. And someone will try and do that. So, when people say that about regulation, I get quite irritated and I tell them: ‘That’s exactly how I’ve taught you not to think.’

Euromoney How did you turn Bank One and JPMorgan Chase into the world’s biggest bank by market cap?

JD When you look at the Bank One/JPMorgan Chase deal there are three things to consider. One was price. That has to make sense for both parties, but put that aside.

The second thing is what I call the industrial business logic. Neither bank was doing great. We both had credit card companies that I’d say were third rate. So when we put them together, we had a much more efficient third-rate credit card company. In consumer branches, Bank One had 2,300 that were making $1 million a year; JPMorgan had 600 in the best locations that should have been making $2 million and were making zero. So, you now had much bigger consumer and had to consolidate.

In cash management, it was much the same thing. In asset management, JPMorgan was much bigger, but Bank One also had a pretty neat asset management business. JPMorgan’s private bank was much bigger. Bank One’s fit right into it. Even in investment banking, Bank One was making $500 million a year in fixed income sales and trading, because you could really focus on FX, swaps and bond underwriting in places where no one else did it.

Bank One had a huge corporate client base with big credit exposure. I said if we bring these banks together, we can reduce our credit exposure and bring a lot more JPMorgan investment bankers to that big client base. Bank One had a great middle-market franchise in the Mid-West; JPMorgan Chase had a great one in New York and Texas.

So, there was huge business logic.

And third is the ability to execute. You may have noticed that the same day Bill and I announced the deal we also announced the management team. Usually in a merger, the two sides wait, try and pick and choose. But we started from day one with weekly and monthly meetings on tech, ops, systems integration, expenses. And the meetings just got better and better. And we also retained more capital and liquidity than other banks.

Euromoney How did that prepare you for the subprime crisis?

JD Coming into 2007, our profit margins had doubled, with capital at 7% while most banks were at 3% or 4%. Also, we had no short-term unsecured funding.

So, we had margins, which had been half what they should have been at the time we consolidated and now were competitive, as one form of protection; capital at 7%, which meant we could take a wallop. I had always done stress testing, not as diligently as we do it today, but asking what would happen to us in a 1974 or 1982 environment if it happened again. I made sure we would be able to run the company and not lose money in a quarter.

And other banks around the world had financed their balance sheets 20% to 30% with short-term unsecured funding. Some of the investment banks had doubled or tripled their leverage. And I used to tell people: ‘Short-term funding is fickle, fickle, fickle.’ It goes away when something goes wrong.

And so, we had zero.

All that put us in a position where we didn’t need liquidity, no one questioned our capital, we were still making money and we were in a position to buy things like WaMu [Washington Mutual] and Bear Stearns.

Euromoney Was it hard to convince people here, before the crisis, that this was the right approach?

JD I was pretty tough back then. I’m not quite that tough any more. I was relentless with people. If you didn’t get it right the first time, you would meet me on a Saturday. And we didn’t lie about the numbers. Everyone got one set. You couldn’t come in and say: ‘Well I don’t look at my business that way’. I would say: ‘No. What should your business be earning?’ People would still try to say there are different ways to look at it. And I would take a chart and say: ‘No. It’s obvious. Our margins are 15%. The average of everybody else is 30%. Just say it. And then analyze why. And then go about fixing it.’

It was constant, constant, constant review and assessment.

And I do mean it about the credit card company, for example. It was not a good business. But we had the core to make one. And then I went and hired Gordon Smith from American Express to run it. And what a home run that was.

The next CEO will be a really important decision. But I think the chance of the next CEO driving this firm in the same kind of direction is pretty high

Euromoney This bank is the product of many mergers. How does it have a defined culture?

JD I was used to doing tons of mergers of companies with really different cultures: life insurance, consumer finance, brokerage. Relative to that, banks have a common culture. But culture is a very funny thing.

I remember we merged Smith Barney and Shearson when I was chief operating officer. And they hated each other. I walked into a meeting one day with 100 Smith Barney managers and they were just bitching and moaning about Shearson and the culture. And I said: ‘You know, we have to get over this. So, I’m going to let each one of you fire one person and after we fire that person I want the hostility to be gone.’ And some of them looked at me, as if they weren’t really sure. And some of them were clapping and saying ‘Yeah!’ But I was kidding of course. I said: ‘I just wanted to see how bloodthirsty you are. Folks, we are going to do the right thing for the right reason.’

And what was the cultural difference? Yes, Smith Barney was more white-shoe and Shearson was more of an upstart. But they all went to the same schools. They were in the same business. They all knew each other. It was just tribal.

Then when it came to Bank One and JPMorgan Chase, Bill Harrison and I put the management team together. He loved some of the stuff I’d written about how we do business, so he asked me to put that together. And I said: ‘I’ll do it. But it’s not a case of I write you a paper and say this is my culture, you have to adopt it. You have to drive it.’

We would meet people all the time through town halls. We would have constant reviews. Get the facts on the table. Share the facts. A balance sheet is not a hypothetical concept. How you treat people is not a hypothetical concept. Follow-up is not hypothetical. People see it, and over time the firm forms a culture that everyone buys into.

Examples resonate. And people see how you do it. You tell the board the truth. You tell shareholders the truth. It becomes very consistent.

Euromoney So, by 2007 that was all done?

JD About two-thirds done. You also have to get rid of the jerks. You give people a chance, but there are people who resist every step of the way. And cultures can go awry too, by the way. You put the wrong boss in a job and I guarantee you the culture will erode. It’s not automatic that you maintain a culture.

Euromoney Do you worry that the culture, the brand, the identity is so wrapped up in you?

JD Yes, I do worry about it. But I think my management team is very high quality. Excellent to a person and on average the best I have ever had. They are really capable people. We have grown up together now. But we do all talk about complacency a lot. And I will be gone one day. The next CEO will be a really important decision. But I think the chance of the next CEO driving this firm in the same kind of direction is pretty high.

They will have to be disciplined. You get huge push-back sometimes. People didn’t want me to do road trips. They didn’t want me to do a lot of things. They’d say: ‘I already do that. You’re reviewing stuff that’s already been reviewed’. And I would reply: ‘Well, let’s review it again.’

Our current leadership group knows that. They won’t be pushed around by bureaucrats who don’t want to work hard. But as I wrote in my chairman’s letter this year, I grew up scrappy. Commercial Credit was scrappy, Primerica was scrappy, Smith Barney was scrappy. And you’ve got to have fire in your gut.

I had someone recently suggest to me that we could save money by opening fewer branches. I felt like throttling them. That is our future

Euromoney You also wrote that you like being the underdog. You’re not the underdog now.

JD I do like being the underdog, and it’s uncomfortable consistently being in the play-offs. Now you’ve got to be careful. As a CEO, you need to keep fire in your gut because if you effectively retire in the job, that’s a disaster. If you take over as CEO of a company – not this company, maybe, because it’s a little different – the staff down the hall will come to you and whisper: ‘Hey, let me explain to you how we handle this, don’t worry about that, I’ll take care of it for you.’ It’s a brain-washing exercise. And before you know it, they own you and you’re in the same stupid position as the person who was running it before.

And you have to have the instinct to say: ‘No. We are going to review that.’ I am going to ask the person who runs Turkey what we should be doing in Turkey. I am not going to ask the person in London that Turkey reports to. You learn over and over and over. And the culture is that people learn to speak up. When I first got here that person in Turkey didn’t speak up. If their boss was there, they wouldn’t say a word.

I always elevate the CEOs who run our different businesses. They drive the businesses. In a lot of companies it’s the other way around: the centre drives the business. For example, Daniel Pinto runs the investment bank here. He reviews his business with me. All the staff here have full access to Daniel. But they are not overriding him.

Euromoney How do you prepare this bank to be a success in an era of perhaps the most rapid technology transformation the industry has ever seen?

JD I agree with you partially but not totally. Technology has always changed this business. When my dad was a broker, you would call the order to the floor of the New York Stock Exchange and they would go into a scrum, write the ticket and sell five days later, and it would cost 35 cents. Now you can do equity with algorithms that cost fractions of a penny.

Paul Volcker once said nothing has ever been reinvented in banking. It’s just not true. Look at straight-through processing, the cost to issue equity and debt, it is much lower than it once was. And along with that comes data and detail and reduced errors and huge inventions like clearing houses, like the DTCC [Depository Trust & Clearing Corporation], that didn’t exist back way back when.

And on the consumer side, real-time payments are here. New platforms like Zelle are here. Consumers can go on their phones and get bill pay and credit scores and offers. These are huge innovations.

I have always told people: ‘You have to use tech to do a better job for your client.’ That’s a sine qua non. So, in our reviews – and this has been true my whole life – we ask: ‘What are you building, what are other people building, how do you make it better, faster, quicker, cheaper?’ And tech is the big part of that. Including for making salespeople on their road trips, with all this at their fingertips, much more productive.

Jamie Dimon and Bill Gates

A few years ago, Bill Gates said banks were dinosaurs. He was dead wrong. I think the chance of disruption is higher. But that just puts more burden on us to use the cloud, big data, or artificial intelligence to win.

That’s why we spend so much money on it. I will spend whatever it takes.

Euromoney How do you make sure you don’t waste money?

JD If you worked for me, I would ask you: ‘Are you building everything that you need to build to win in the future?’ And you’d better say: ‘Yes’.

Euromoney But I would say I don’t know, because I don’t know what will win in the future

JD Then you should be testing and learning. Have you looked? Have you assessed the landscape? But if you need this, this and this, they have to be in your agenda. They have to be in the budget. If someone says to me: ‘We should have built that a year ago, we knew we should, but we couldn’t afford it,’ I’ll say: ‘Excuse me, we could afford anything you want, you should have put it in there.’ Never again will I say that I didn’t build something that we should be building, that I knew about, because we can’t afford it. Never again. It is unacceptable.

Now of course that makes it easy to spend money. And people like Daniel and Gordon will say: ‘Don’t make it that easy, Jamie.’ And I will say: ‘That doesn’t mean you can’t do it more efficiently.’

It is just like branches. I had someone recently suggest to me that we could save money by opening fewer branches. I felt like throttling them. That is our future. We are going to build these things. We are going to hire bankers. But it’s perfectly reasonable to say: ‘Hey, you know what, we’re not actually that efficient when we open new branches. I can get them up to profitability faster. I could have eight people not 12. I could make it better.’

And that’s true for technology. For P2P [person-to-person], I want us to build Zelle. If it costs a lot of money, sure I’d like to do it for less. But don’t not build it.

Euromoney How do you manage this kind of technology investment?

JD We have a timetable. And in our reports you’ll see the original due date and then the amended due date, not because we punish people for being late, but so that it’s fully disclosed. You’ll see mission creep and you’ll also see mission reduction. You start off saying you’re going to build the best platform ever and before you know it, you didn’t. So, we have a lot of action reports that ask what did we do, what did we miss, what did we learn, what did other people do it for.

There are some benchmarks. But I don’t require people to net present value all these projects. NPV’ing could take six months. We could have the product in that time. For a lot of these things, these are just table stakes. Do it efficiently, but just build the damn thing.

I remember when I first got here some of the investment bankers telling me that the consumer bank was holding them and the company back. I told them: ‘No. You’re doing a shitty job all on your own

Euromoney You have said you were late with the cloud. Why was that?

JD Partly that was down to me. Both Bank One and JPMorgan Chase had outsourced a tremendous amount of technology, including programmers, data centres, networks, help desks, you name it. It was about 25,000 people between the two companies. And I brought it all back in.

Euromoney So, it’s a control issue?

JD It’s partly a control issue, but it’s also an integration issue. If you’re the tech person, you have to be talking all the time to the sales and marketing people.

But I originally thought of cloud as just another word for outsourcing. I can run data centres as efficiently as anyone outside; we can run networks, we can do programming as well. But we missed a point. The cloud platform is so much more efficient. In the old days, if we were using all this data to do risk management or marketing, to add a new database, you had to write a lot of code. That might take six months. Then you’d have to back test. Now you can just click and drop, and it’s in your database and it’s running AI the next minute.

We are building our own cloud platforms here too. So, we have an internal cloud, a private and a public cloud. I was worried about security, but it’s pretty secure and, in some ways, it’s more resilient. We are going full speed ahead.

We are still learning. And now we bring our discipline. We have 6,500 apps. Some may be retired. Some may go into the cloud. Each one has a due date by which time it is going to be re-factored. Senior people will decide whether each goes to the public cloud or private cloud, how critical the security of that data is. And there are solutions for most of these questions.

Euromoney Does a bank know more about its customers than an Amazon or Facebook?

JD I don’t know. They all have a tremendous amount of knowledge, which is different. In some ways a bank knows more, Amazon knows more about retail purchasing habits. We know where you travel, where you stay, where you eat, your spending habits. We know where you’ve used your credit card. We don’t know what you’ve bought. They know what kind of sneakers you buy. My daughter uses my Amazon account too, so they must think I go from buying sneakers to buying maternity clothes.

Essentially the difference is we can use data for our own risk, fraud, underwriting, marketing. But we can’t send data to third parties at all.

AI and cloud are real. We spend $600 million a year on cybersecurity. We educate customers on cyber. Even though cyber is one of the major risks that banks face, that has become a competitive advantage for JPMorgan.

Euromoney What have you learned from the mistake about the cloud?

JD The management lesson is: maybe I was wrong about the cloud and outsourcing. People didn’t fight back at me enough. And the second I saw it for myself, I told the management team responsible for technology two things: number one, you should have told me; number two, do it as fast as you can. I don’t want to analyze it. I don’t want you to use consultants. I want you to hire 10 to 20 brilliant cloud people and start doing it and that way we’ll learn and learn and learn. And do it fast.

Euromoney You clearly think deeply about this, and many other issues besides, judging by the length of your chairman’s letters. Where do you find the time to think about, and then write about, these things?

JD I accumulate information. When I started the chairman’s letters, I made a list of all the things a shareholder might want to know, an employee might want to know, a customer might want to know. So, where are we with cyber and cloud? Where are we, ahead of or behind other banks? If you read those chairman’s letters, there’s the good, the bad and the ugly. I show the mistakes we made.

I showed the post mortem on Bear Stearns and WaMu. What did we learn? What can we do better? And I want the people here to see how action reports, maturity about problems, not pointing the finger at people or firing them because they made mistakes are all part of being very honest about what we do.

And I take time to do it, probably one full week and five full weekends. To me it’s a learning exercise. I’m answering questions. How bad is student lending? I think it’s bad, but now I’m going to analyze it, get the research numbers, get the facts. And, yeah, turns out, it’s pretty bad.

Euromoney Banks are still criticized a lot. Is that fair?

JD A bank is different than a normal company. If you walk into Walmart and you have cash, they will sell you what you want. If you walk into a bank, whether you are a consumer or a corporation, and you want something, half the time we say: ‘No’. We are a financial partner that tries to bring needed capital discipline.

America has the best environment in the world: rule of law, transparency, ability to buy and sell freely, across the whole mosaic – venture capital, private equity, hedge funds, banks, non-banks. Now you may not like ’em all, but you don’t question that stuff here.

That proper disciplined allocation of capital – even if you do sometimes make mistakes – is critical to the functioning of a healthy economy.

Now I understand why people get mad when banks say no. Sorry you can’t have a credit card, we’re not giving you a checking account, we’re closing your account – sometimes we have no choice by the way – but you need that capital discipline.

Dimon with other US bank leaders at a Congressional hearing in April

And the vibrancy of the financial system has been crucial to the success of the US economy compared to some other parts of the world. Look at China for example, where you have a system based on undisciplined allocation of capital.

Euromoney Should a bank chief talk so much about public policy?

JD Some things are progressing so slowly that I do get frustrated. I have a deep frustration about what we are missing. You need to do your research properly and your analysis has to be comprehensive and presented year after year as a means to show what we are missing: for example on infrastructure, on litigation, where our costs are double what they are anywhere else in the world; on education, which is especially important now that low-paid employment is no longer providing a living wage for many of those that have been failed by the education system.

Euromoney Beyond pointing this out, what can banks do?

JD Traditional banking is what we do. But I would point to some of the things we have done in Detroit, for example, as a form of venture banking. This is not philanthropy. It is not just writing a cheque. Like everything else we do, it is carefully studied and analyzed and measured and followed up on. It’s not a question of how much money did we make available: it is how many kids did you train, how many affordable housing units got built. And I think being involved in all of that has made us much better as a company.

Euromoney Must it have a tangible return?

JD This whole primacy of shareholder value thing – I have never believed in it. Banks need to take care of their customers obviously and also of their communities, of their employees. We need to work with governments to improve society. Having a fortress balance sheet is about keeping ourselves healthy. But if you are healthy and society is sick, you are still going to suffer.

Euromoney You have the biggest market cap and highest book value per share in the industry. What’s next?

JD Maybe there is no ‘what’s next’. Maybe we can have a superior return for ever. One of the mistakes Citi made when they were doing really well is that it was never enough. They wanted to do even better and to improve operating margins even further. You can do that in the short term, but if you seek to maximize short-term returns, that might leave you dead in the long run.

And we will never boost returns by cutting the investments we need to ensure we will have a profitable future.

We are running at a 30% return on equity in consumer banking. But we won’t improve that by failing to refresh branches or by closing branches or by not opening new branches in promising locations.

Euromoney You clearly wouldn’t swap the business mix you have here for anything else.

JD I remember when I first got here some of the investment bankers telling me that the consumer bank was holding them and the company back. I told them: ‘No. You’re doing a shitty job all on your own. The consumer bank is not holding you back.’ And in fact, it is because we have earned so much in consumer at home in the US that we might be able to invest and build the investment bank more overseas.

It is a competitive advantage for the investment bank that we are strong in consumer. And there is also no successful commercial bank of scale that does not also have consumer banking and the branches, which also really matter to commercial banking.

So, when we merged Bank One and JPMorgan and some investment bankers wanted me to close branches I said: ‘No, we will bring JPMorgan investment bankers to the customers of those branches. You won’t cover companies based in Austin out of New York, because they will hate you.’

And today, something like 25% of our investment banking revenues in North America come from serving those commercial banking clients that we bank so well all across the country.