In financial services, much of the institutional and regulatory focus on the ethics of technology has been on the misconduct and market abuse issues raised by trading algorithms in FX and securities markets. However, all of these issues arise in retail banking too. Building a framework, defining ethics in terms of code, removing coders’ own biases and ensuring that these new technologies remain within ethical parameters remains a complicated but critical work in progress.

Bias in, bias out

One reason for this is that at the heart of all the intelligent technologies being developed is data, huge amounts of it. The more data to ‘train’ the models, the better. However, if data is biased, conclusions will be biased. So, if a bank wants to build a system that identifies the best customers to grant mortgages to, an algorithm might compare current applicants with the historical data and conclude from past lending patterns that people from rural areas or particular ethnic groups should be refused credit, as they feature less frequently in the data, having been subject to discrimination in the past.

This creates a stumbling block. It means that ethical considerations and fairness must be built into models from the start, not bolted on as an afterthought, to ensure that the datasets used to train self-learning models do not perpetuate the undesirable social effects they record.

Pere Nebot, chief information officer at CaixaBank, Spain’s leading retail bank and financial institution at the forefront of digital transformation, acknowledges these issues: “CaixaBank is investing in this area and participating in industry initiatives around an ethical framework for the use of AI. There are biases in society, whether by gender, race or sexual orientation, and we assure none of them are translated into the algorithms to avoid reinforcing these biases into society through automatic decisions.”

Can AI help you?

These types of algorithms and machine-learning solutions tend to operate at one remove from the customer. They make decisions that affect customers but they do not interact with them directly. However, artificial assistants, (chat)bots and robotic process automation solutions do. And that raises a whole new set of issues.

Artificial assistants are becoming extremely widespread. These tools can interact either through text windows or, in the more advanced versions, through voice. They rely upon natural-language processing (NLP), the science that turns the complicated and error-prone utterances of people into data understandable by a computer, and which allows the computer to answer in speech that a human can understand.

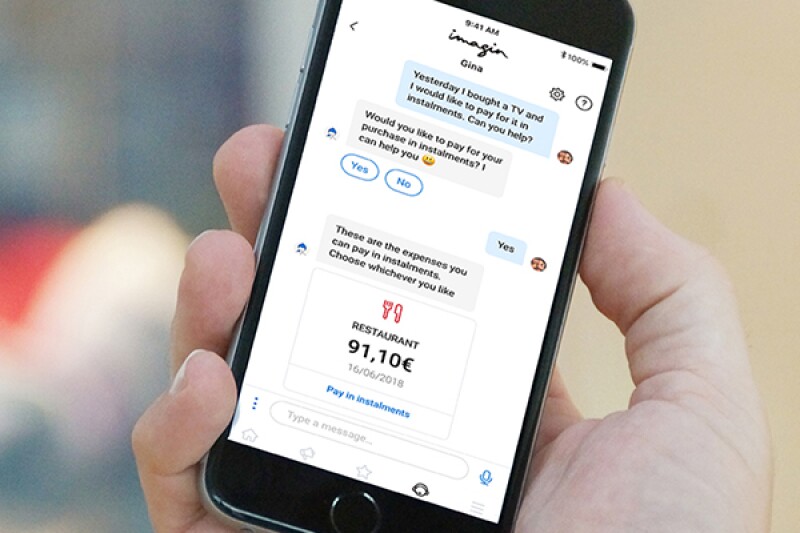

CaixaBank’s Neo, built into the CaixaBankNow app and also accessible via Google Home and Alexa, can answer up to 1,000 different voice or text questions from customers, based on training on 50,000 different questionnaires. Gina, the imaginBank chatbot, accessible via Facebook and the imaginBank app, is similarly designed to answer common customer queries. But they are smarter than that, and they are getting smarter all the time.

Both Neo and Gina, for example, can proactively suggest personalized products and services based on individual customer profiles and behaviour. And most recently, Gina has added the ability to intelligently suggest the best ways for customers to make their credit payments, making it one of the first chatbots to actually manage real funds in real time. Big Data and AI are used in two ways to enable this. Gina can analyse the data to proactively propose an instalment payment plan. Or the client can directly request via voice message or text the payments they would like to split into instalments, and Gina is able to look at the latest transactions and select the correct payment.

This raises interesting ethical and cybersecurity questions if clients believe the machines to be human. Does it matter if you are talking to a bot or a person? Some people would say that it does: the person will have been trained and will, one hopes, have a moral framework, a sense of responsibility, and a work contract that constrains their actions. Can we be so sure about the bot? And what if you are discussing personal financial information? Is it more secure with the human or the machine? Banks must work to find answers to these questions.

According to CaixaBank’s Nebot, “Chatbot technology can amaze us with its sophisticated conversational characteristics, but we need to remain conscious of its impact. Those of us working with these technologies need to be sure that we fully comprehend the impact, ensure a positive impact, and most importantly, that we understand what can really add value to our customers to increase their satisfaction.”

The challenge of digital labour

Another key area in which banks’ digital transformation journeys encounter ethical complexity is robotics. In this context, robots are the software agents of so-called robotic process automation (RPA). RPA is the automation of an increasing number of – initially – repetitive, manual processes. As these solutions grow in sophistication, it is becoming clear that entire classes of job are likely to be fundamentally changed, or even rendered obsolete.

The creation of an automated workforce that can replicate many of the functions currently executed by humans will transform the service industries just as robots have transformed manufacturing over the past 40 years. However, historical evidence suggests that while certain jobs may be at imminent risk, new jobs usually appear in the long run, although these will be highly dependent on the development of new technology-related skills.

That said, the mix between robotics automation and human skills, and taking advantage of both components, will be crucial to future success. But as customer buying preferences increasingly correlate with the perceived ethics of organizations, solving this, and the other ethical dilemmas posed by new technology, may also be the key to competitive advantage in this era of digital transformation.