| Authors |

|

|

Samuel Mathew |

|

Biswajyoti Upadhyay (BJ)

Head of Transaction Banking Hong Kong, Standard Chartered Bank

|

Even as the United States threatens to impose a fresh round of tariffs starting in September, it is clear that the first tariffs imposed in 2018 are having a powerful effect on trade flows.

China may be losing significant market share of the targeted imports, such as textiles, garments and electronic goods, but other countries are winning much of that share. Nearby Asian markets – Taiwan, Malaysia, the Philippines, Cambodia and Vietnam – have gained most, while countries further afield, such as Mexico, also look to be early winners.

The two rounds of US tariffs already in place cover thousands of products, mainly electronic, with an import value of $250 billion[1] – a substantial slice of China’s US exports. There is also the smaller amount of China’s retaliatory tariffs, covering $110 billion of imported goods.[2]

While the United States and China returned to the negotiating table after the June G20 meeting, differences that started with trade have now become more entrenched, extending to technology leadership and security.

Following the Shanghai round of trade talks at the end July, the US has again threatened to impose a 10% tariff on an additional $300 billion of Chinese exports to the US, effective from September 1, 2019. This is despite proposed further talks between the two countries, expected in September.

Against such an uncertain background, businesses have acted where it is easiest to do so. Commodity traders quickly reacted to China’s tariffs on US agricultural commodities, directly switching orders to Brazilian farms. As time goes on, the US businesses that are able to do so are shifting their supply chains away from China, mainly to other low-cost countries.

Within affected businesses, treasurers are in the eye of the storm. As the tariffs’ ramifications strike home, multinationals face issues over liquidity structures and heightened counterparty risk, owing to the introduction of new trade partners and country risk. Chinese exporters will need to have robust financial liquidity to weather any downturn in orders or look to other Asian corridors, such as Indonesia or Malaysia, for exports.

The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) region has already replaced the United States as the second largest trading partner for China – behind the European Union – in the first half of 2019.

China loses, others gain

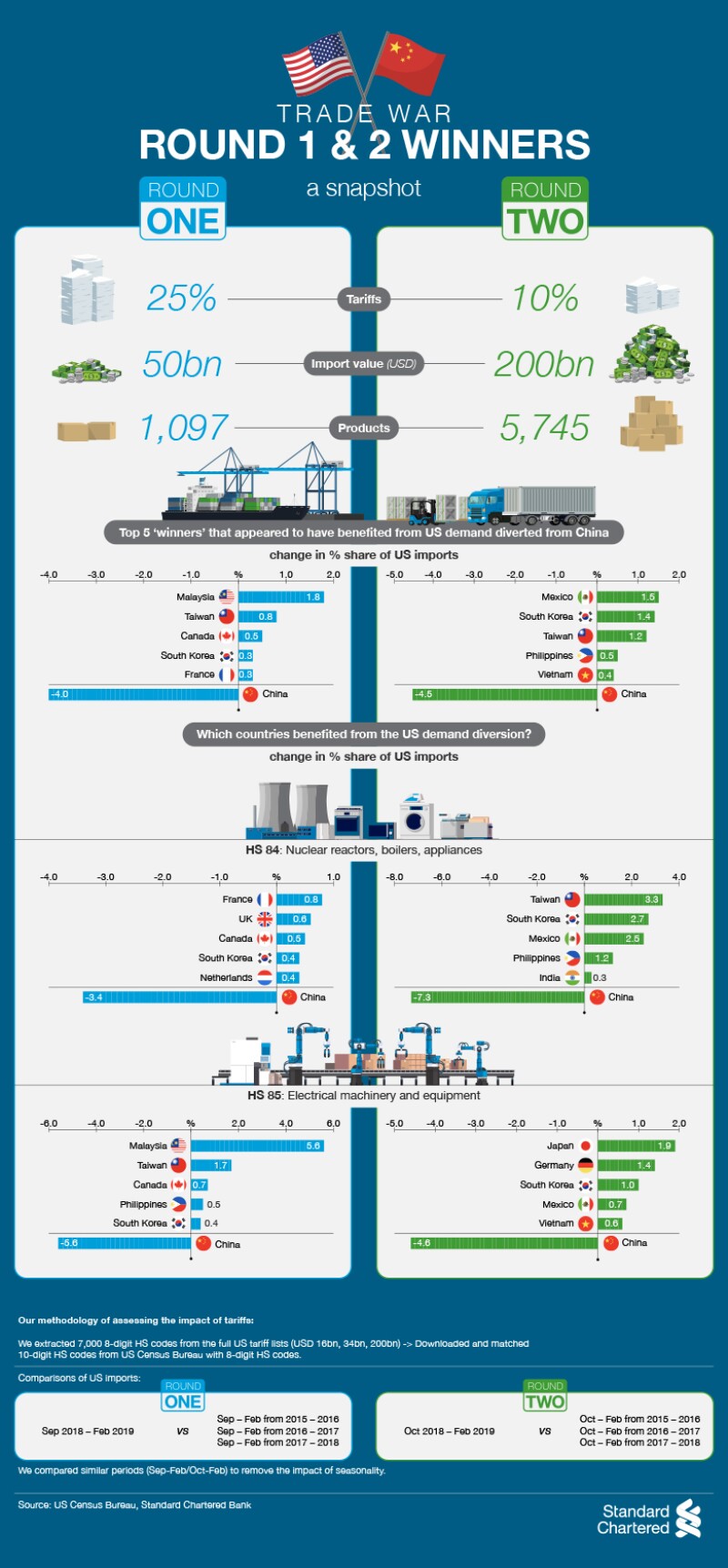

Our analysis (see Fig.1) shows two rounds of US tariffs are having the desired effect – shrinking China’s share of US imports. Targeted products include a broad range of chiefly electronic goods, including washing machines, telephone equipment and televisions, as well as agricultural machinery and machine tools. In round one, $50 billion worth of goods suffered 25% tariffs, resulting in China losing 4% market share. The second round of tariffs was more ambitious – levying 10% tariffs on $200 billion worth of goods – increasing China's loss to 4.5%.

But which markets gained? Malaysia was the biggest winner from round one, taking 1.8% market share, followed by Taiwan’s gain of 0.8%.[3] Turning to round two of the tariffs, Mexico gained 1.5% and South Korea 1.4%.[4] Other winners, to a lesser degree, included Vietnam, the Philippines and even high-cost economies such as the United Kingdom and France. While the United States continued to import consistent volumes of the targeted products after round one, imports fell slightly after round two.

Manufacturing on the move

The introduction of tariffs has accelerated shifts in supply chains and manufacturing that were already under way. Multinationals are moving to procure low-end electronics goods from countries such as Vietnam, although the quality of manpower and infrastructure are potential problems. Chinese companies’ production lines in Mexico – previously serving Latin America – are expanding capacity, and in Taiwan local companies are reopening factories. Meanwhile, US retail companies buying from China are scoping out new potential markets, like Bangladesh. China still exports the bulk of the high-end textiles to markets like Vietnam, due to highly automated manufacturing and quality control.

In China and Hong Kong, times are leaner. Export orders that normally increase in the second and third quarters, after Chinese New Year, have not done so this year. Some companies are reporting lower sales and operating profits, and consequently cutting manpower in southern China.

China’s central bank has sought to pre-empt any economic difficulties by slashing reserve requirements for banks, reducing the cost of lending. At the same time, the central bank is acting to stabilise the renminbi, or yuan, against the US dollar.

Treasurers manage disruption

Chinese companies may face greater challenges, if either their exports fall or domestic consumption declines. What will happen to their liquidity and bank credit lines then? For multinational companies procuring from China, counterparty risks may be rising. There is a clear shift of low-end, labour-intensive manufacturing out of China, whereas value-added, high-end manufacturing remains the country’s domain of expertise.

While the high stakes poker game between the United States and China is still being played out, businesses have little choice but to act if they are to manage the disruption to their operations.

From a country perspective, although China is currently losing market share, there are other countries that are clearly benefiting.

Fig. 1

[1] China Briefing. The US-China Trade War: A Timeline. July 25, 2019.

[2] China Briefing. The US-China Trade War: A Timeline. July 25, 2019

[3] Change in % share of US imports of HS 84, 85, 90, Sept – Feb 2018-2019 vs average of same period over previous three years. Sources: US Census Bureau, Standard Chartered Research.

[4] Change in % share of US imports HS 85, 84, 94, 87, 73 Oct – Feb 2018-2019 vs average of same period over previous three years. Sources: US Census Bureau, Standard Chartered Research

About the Authors

|

Samuel Mathew, Global Head of Documentary Trade, Transaction Banking, Standard Chartered Bank

Based in Singapore, he is responsible for product capabilities, product financials and commercialisation of cash management, trade and securities services products for Standard Chartered in the southeast Asian markets. Mathew joined the bank in 2004 and his previous roles include global head of collections product solutions and regional product manager in charge of receivables solutions for Asia. He has more than 15 years of transaction banking experience. Prior to joining Standard Chartered, Mathew has also worked with Citibank NA and Deutsche Bank. Mathew is a graduate of Bombay University, Mumbai with First Class Honours in Engineering and holds an MBA from Nanyang Business School in Singapore.

|

Biswajyoti Upadhyay (BJ), Managing Director, Head of Transaction Banking Hong Kong, Standard Chartered Bank

Biswajyoti Upadhyay (BJ) is Head of Transaction Banking HK. He also assumes the responsibilities as Greater China & North Asia Regional TB Co-Head. His role encompasses managing the business end to end. He is designated as a material risk taker and interacts with regulators on product roll out and risk governance. He has been in HK for 4 years during which he was Regional Head of Trade, Transaction Banking for GCNA. He has been instrumental in driving the trade digitization plan with blockchain led platforms with HKMA and PBOC.

| Disclaimer

This material has been prepared by Standard Chartered Bank (SCB), a firm authorised by the United Kingdom’s Prudential Regulation Authority and regulated by the United Kingdom’s Financial Conduct Authority and Prudential Regulation Authority. It is not independent research material. This material has been produced for information and discussion purposes only and does not constitute advice or an invitation or recommendation to enter into any transaction.

Some of the information appearing herein may have been obtained from public sources and while SCB believes such information to be reliable, it has not been independently verified by SCB. Information contained herein is subject to change without notice. Any opinions or views of third parties expressed in this material are those of the third parties identified, and not of SCB or its affiliates.

SCB does not provide accounting, legal, regulatory or tax advice. This material does not provide any investment advice. While all reasonable care has been taken in preparing this material, SCB and its affiliates make no representation or warranty as to its accuracy or completeness, and no responsibility or liability is accepted for any errors of fact, omission or for any opinion expressed herein. You are advised to exercise your own independent judgment (with the advice of your professional advisers as necessary) with respect to the risks and consequences of any matter contained herein. SCB and its affiliates expressly disclaim any liability and responsibility for any damage or losses you may suffer from your use of or reliance on this material.

SCB or its affiliates may not have the necessary licenses to provide services or offer products in all countries or such provision of services or offering of products may be subject to the regulatory requirements of each jurisdiction. This material is not for distribution to any person to which, or any jurisdiction in which, its distribution would be prohibited.

You may wish to refer to the incorporation details of Standard Chartered PLC, Standard Chartered Bank and their subsidiaries at https://www.standardchartered.com/en/incorporation-details.html.

|