A lush green meadow brimming with butterflies, insects and wildflowers is flanked on one side by old oak forests dripping in lichens. Along the other side rise up Sitka spruce, home to eagles, below which 40 or so sheep are taking shade. The sound of bees is almost overwhelming as they leave the 15 apiaries here, not only to enjoy the wildflowers but to feast on the pollen of chestnut trees planted in wide rows across several hectares the other side of the spruce and meadow. It is a mosaic of productivity and health.

This slice of heaven outside the city of Bragança in northern Portugal is the three-year creation of André Rebelo, who owns the farm and the nearby chestnut factory. Each individual business connects to the other in an ecosystem that is replenishing the soil, generating carbon sequestration, enriching biodiversity, producing nutritional food and mitigating climate and fire risk.

It also generates jobs and profits.

Twenty-five employees work the 200 hectares, carrying out controlled burning in winter of the shrubs on the forest floors to support the oaks, chestnuts and pines. They harvest the chestnut honey, direct the sheep grazing to ready them for market and prepare land for crop rotation. They pick the chestnuts that make their way to buyers across Europe and the US, and tend to the organic vegetable patches. From human to insect to soil organism, every part of the ecosystem is vital and therefore needs to be supported.

It’s a model so removed from industrial farming methods that it doesn’t really have a name yet.

“Some people tell me it’s agroforestry or sustainable land management,” says Rebelo.

The more fashionable term now seems to be regenerative agriculture or, more accurately, organic regenerative agriculture. Above all, it is a vision for the vast areas of agricultural land in Portugal that have been abandoned as people have left for jobs in the cities; land that is now a tinder box as biomass builds and temperatures rise.

Portugal has lost more of its forest to fires since the start of the decade than any other southern European country.

“Farming in this way can be supportive to humans and nature, and can help communities become more resilient to changes in climate and natural disasters,” says Rebelo.

Not only is Rebelo a farmer, forester and businessman, he is also a trained firefighter and advises the Portuguese government on forestry and fire mitigation.

But the model is not just a vision for Portugal and its abandoned farms. It’s a model that could solve the global collective dilemma. With the population expected to increase to nine billion by 2050, the world needs to be more productive, but farming practices are killing the soil and biodiversity, causing farmers to abandon their fields, poisoning waterways and producing food that is lacking in nutritional value.

According to the latest IPBES Global Assessment, through land degradation, chiefly from using agrochemicals, the world has lost approximately 8% of total global soil carbon stocks over the last 200 years, reducing productivity in 23% of the global terrestrial area.

Due to chemical use, between $235 billion and $577 billion in annual global crop output is at risk as a result of pollinator loss.

The way we produce food can either help communities and nature flourish, or put both at risk. Right now, it is doing the latter - André Rebelo

A report from the Food and Agriculture Organization of the UN last year highlighted the role agriculture is also playing in water pollution. In most high-income countries and many emerging economies, agricultural pollution is now the biggest factor in the degradation of inland and coastal waters.

“Nitrate from agriculture is now the most common chemical contaminant in the world’s groundwater aquifers,” the report says.

It’s a global issue. In the European Union, 38% of water bodies are under pressure from agricultural pollution. In the US, agriculture is the main source of pollution in rivers and streams. In China, agriculture is responsible for a large share of surface-water pollution and is responsible almost exclusively for groundwater pollution by nitrogen, says the report.

Agriculture is also the largest producer of the greenhouse gases (GHGs) methane and nitrous oxide – 25 and 300 times more effective than CO2 at trapping heat in the atmosphere, and both increasing rapidly.

“The way we produce food can either help communities and nature flourish, or put both at risk. Right now, it is doing the latter,” says Rebelo.

A revolution is beginning however. In countries around the world, governments are echoing Rebelo’s point. Food, beverage and fashion companies are examining how they can transition their supply chains to support regenerative practices. And farmers themselves are turning to chemical-free practices and applying mixed-used land models that support biodiversity.

The positive news is that as farmers make the shift they are finding, like Rebelo, yields improve, pollinator numbers increase, land is healthier and more resilient to change, and communities are strengthened. But they need the finance and investment to make the transition.

Andre Rebelo on the hills of Braganca

Systemic change

“It all starts with soil health. This we know now,” says Eric Soubeiran, vice-president of nature and water cycle at Danone. In 2018 Danone North America committed $6 million over five years for a soil regeneration research programme working with universities and data analysis firms.

“When you’re on the field every day with farmers, as we are in our business, you can feel the pace of what is happening. The intensification of agriculture that we have been a part of has had its benefits, but we must all now acknowledge its limits. The soil is depleted, yields are reducing, and it’s high time to propose new models.”

He points to the need to adopt a multi-stakeholder approach between farmers, manufacturers and public authorities to find sustainable solutions.

“There’s an opportunity here to advance a model that is different – one that brings back and rebalances nutrients in the soil and disconnects farmers’ dependency on synthetic agrochemicals,” he says. “Such models are economically viable: they bring savings on inputs, they restore natural soils’ resiliency and that should be the foundation of a systemic change.”

The model is simple and it’s becoming a hot topic. Regenerative farmer Gabe Brown was even cited during the US Democratic Party’s presidential candidate debates as having a model a future US government should consider. Brown began farming on 5,000 acres in North Dakota in 1991, quickly moving to no-till farming that allows soil to recover. With others, he now advises other farms, as well as politicians.

“People talk about sustainable agriculture, but why would we want to sustain a degraded resource?” says Brown. “We have to fix the soil first, which is why this is a regenerative movement.”

There are six primary principles to regenerative agriculture, Brown explains, the first being to farm in context.

“You shouldn’t be trying to produce corn 300 miles north of the Canadian border,” says Brown.

The second is to create as little disturbance to the soil as possible, which means no tilling and as few pesticides and fungicides as possible.

“You may have to wean the soil off [for] the first couple of years, but after that there’s no real need for inputs,” he adds.

The third is “to put armour on the soil” through crop cover or allowing weeds to come through.

The fourth is to have diverse ecosystems.

“Nature abhors a monoculture, yet we don’t see any diversity in our large swathes of dairies or cereal crops,” says Brown.

Number five is to leave roots in the soil for as long as possible, which means no cash crops with 100-day maturities.

And the sixth principle is to integrate animals (both livestock and wild animals) and insects to create an ecosystem.

Under the current model, most producers are grossly over-applying fertilizers, pesticides and fungicides and spending money where they don’t have to - Gabe Brown, regenerative farmer

Much like Rebelo’s farm, Brown has multiple enterprises with sheep, hogs, bees, fruit trees, vegetables, crops and cattle.

The grazing of livestock improves soil health, while allowing more carbon to be taken from the atmosphere and cycled into the soil.

“Grazing ruminants allow methanotrophs to consume the methane that they omit,” explains Brown. “Farmers will come to my ranch and say: ‘Oh, this looks like an ordinary ranch.’ But then they notice the diverse plants, the insects, birds and wildlife, and then I show them the soil and how much water it can hold – and they realize it’s a very different proposition.”

The practices have made Brown’s farm resilient against flood risk and thanks to diversification he is resilient too to volatility in prices. Yields are high, as is demand for Brown’s farm products from a consumer market looking for healthy and traceable foods.

Brown says there is a misconception that a transition away from conventional farming will mean losing money.

“It’s just not true,” he says. “We consult now on a lot of land, and I’ve yet to see profitability not increase the first year if not simply from cost cuts. Under the current model, most producers are grossly over-applying fertilizers, pesticides and fungicides and spending money where they don’t have to.”

The use of agrochemicals and genetically modified organism (GMO) seed has put farmers in a dependency cycle as soil health has diminished.

“Farming and ranching has the highest suicide rates of any business in the US,” says Brown.

And the US farmer suicide crisis echoes a much larger one happening globally.

In Australia, one farmer commits suicide every four days, in France it’s every two days. In the UK, one farmer a week takes their own life. In India, more than 270,000 farmers have died by suicide since 1995.

“We have a quality-of-life issue, but we need farmers, which means we need them to be happy,” says Brown.

Gabe Brown, regenerative farmer

He is a convincing spokesperson for the transition away from conventional intensive farming methods, but farmers are understandably nervous about low production years if the soil needs to recover. It is something Danone has found as it seeks to transition the farmers within its own supply chain towards regenerative practices.

Indeed, supply chain conversion may be the means by which a large-scale shift to regenerative agriculture occurs – if the financing is there.

In North America, Danone has converted about 65,000 acres to non-GMO cropland to provide feed for the cows that make milk for its non-GMO Project Verified products. It aims to convert half of its entire volume of products by 2020.

The strategy has required a reinvention of Danone’s pricing model for milk. Soubeiran says farmers need more clarity about their earnings to be able to transition to new practices – such as organic or regenerative agriculture.

“This is one reason why we decided to set our milk price based on the cost of production,” he says.

How that price is reflected in the final consumer product is still being tested.

But the cost of transitioning needs to be paid for. Soubeiran says it takes between 24 and 36 months for a farmer to fully transition to a profitable regenerative organic model as the soil recovers. At present there aren’t the financial tools to help.

He says: “The current instruments were created after World War II and were designed around capex financing and intensive farming. The lack of an updated financing model is slowing down farming conversion.”

Regenerative agriculture models developed by Danone can offer a 7% to 8% return on investment, far outstripping current interest rates on loans, yet the financing of this transition is perceived by banks as risky and requires a longer time horizon than the market currently supports.

Soubeiran suggests the public sector could provide the first-loss portion with private capital stepping in behind.

“Monetizing the positive externalities of regenerative agriculture practices that restore soil organic matter is critical to solve this paradigm, as is the repurposing of key agricultural subsidies,” says Soubeiran. “While corporates will be ready to guarantee and off-take the repurposing of this, public financing could serve as a first-loss guarantee and therefore unlock private financing for the regenerative agriculture transition.”

Danone is talking to several partners to develop the idea.

“This needs to be top of mind in the financing community,” Soubeiran adds.

Perceived risk

One bank where it is top of mind is Rabobank – one of the world’s largest agribanks.

Last year it teamed up with the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), the Dutch development bank FMO, and sustainable trade initiative IDH to develop the Agri3 Fund. The fund is designed to mobilize $1 billion in finance from commercial banks and other financial institutions towards sustainable agriculture, the prevention of deforestation and improving rural livelihoods in central and south America, Africa and southeast Asia.

Agriculture is responsible for 75% of all deforestation – that’s partly why it’s such a large emitter of greenhouse gases – but it is easier for a farmer in a remote rural village to cut down trees to find more fertile soil than it is to find funding to support a transition. Often, any loans available would also come with unaffordable interest rates.

Farming is a complicated industry with many variables, and is perceived by many banks as risky. Not many commercial banks do lend to farmers. They don’t like the cyclical nature - Hans Loth, Rabobank

One of the fund’s reasons for existence is that, as Soubeiran argues, there is little appetite for the perceived risk or up-front costs of helping farmers transition to more sustainable practices. A point echoed by Hans Loth, Rabobank group executive.

“Farming is a complicated industry with many variables, and is perceived by many banks as risky,” says Loth. “Not many commercial banks lend to farmers. They don’t like the cyclical nature. We, however, understand the risks as we’ve been in the business a long time – but even we have risk appetite challenges around the demand for loans at longer tenor to allow for transition periods.”

In Agri3, donors and investors will de-risk the difference between a five-year loan (the current typical length) and a seven-year loan – providing grants for technical assistance and junior capital.

“It de-risks the default risk, because in those first two years of transitioning, the farmer may not be able to make the loan repayments and may be in debt for a short period before yields go back up,” says Loth.

|

| Hans Loth, Rabobank |

The commercial and development banks contribute to the senior debt of the finance portion of the fund. They will also lend $700 million directly to projects and farmers.

Rabobank is working with its food and agriculture clients through their supply chains to source farmers in developing countries.

“Corporate clients are only too pleased because they want to convert their supply chain to sustainable agriculture,” says Loth.

What this means for the fund is access to farmers on the ground that would not typically be found by traditional impact investors.

“That is what is so exciting,” adds Loth. “We can reach at such a large scale smallholder farmers in developing countries.”

The typical contribution by the fund for each investment will be in the range of $3 million to $15 million to enable projects from $10 million to $150 million.

So far, several small-scale pilots have been run in Brazil to show investors how the impact can be made by combining technical assistance for farmers with the loans.

Agri3 is building its pipeline now before it goes out to speak with donors and investors, and Althelia-Mirova has been picked to run the fund.

New financial model

In the North Island of New Zealand, in the region of Waikato, a new financial model is also being developed that may provide ideas for funding farm conversions with private financing by using an impact-investment model.

One million tourists a year visit Waikato to enjoy its rolling hills, wild beaches, caves, lakes and rivers, and of course, Hobbiton. But what makes Waikato the fourth-largest regional economy in the country isn’t tourism but farming. It has 4,200 dairy farms.

However, the impact of such large-scale farming on the water quality of the Waipa and Waikato rivers that run through the region has raised public concern and there is increasing pressure to curb environmental degradation and to reduce greenhouse-gas (GHG) emissions.

A report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change in August estimated between 25% and 30% of total global GHG emissions are attributable to our food system. In Waikato, some 75.5% of the region’s GHG emissions are from agriculture – and net emissions are 50% higher in Waikato than the national average.

Impact investment company, Envirostrat, is helping to develop an investment project that will convert the land use in a way that is supportive of farmers, natural resources and New Zealand’s economy.

Nigel Bradly, founder and managing director of Envirostrat, is leading the project and has been looking at private financing from the beginning.

“While governments grapple with impact investing and their role within that, my stance is that private capital should really be the focus,” he says. “If we can get impact projects funded which are commercially sound and therefore not at risk of changes in government policies, then we’ll start to achieve our environmental targets much quicker; and the private markets will then run with it.”

|

Of the 130,000 hectares being studied, 7,000 were highlighted as hotspots where conversion of land use would have the biggest impact; and investors have been approached to gauge who would invest and what they would want.

“You have to have a deep understanding of what investors want in conservation projects and build to that,” says Bradly.

It turned out that what investors want is different to what was originally considered. Many different revenue streams to pay for a conversion were scoped – ecotourism, carbon offsets and diverse crops, such as manuka honey. What investors feel comfortable with, however, is financing a straightforward conversion from conventional to organic dairy and owning the hard assets of the farmland.

“While we had been focusing on water-quality improvements and biodiversity enrichment as main impact goals, we found investors were increasingly interested in GHG emission reductions and carbon sequestration, as concern about climate change is increasing,” says Bradly. “In the end, the project’s benefits to biodiversity and water quality remain the same as we had planned through the measures we will carry out on the land, but we are prioritizing the impact objective on producing a 40% to 60% decrease in GHG emissions.”

Cerasela Stancu, sustainability director of Envirostrat, says: “It doesn’t mean we aren’t going to carry out other land-use change and mitigation initiatives like afforestation, riparian planting, wetland restoration, biodiversity corridor creation, prevention of nutrient leaching – these interventions are all inter-linked and our job is to assess them and invest in those that generate benefits across the board.

“We want the projects to be ‘organic-plus’ – essentially leverage the certified organic premiums to finance the transition to a regenerative farming model that increases soil health, reduces erosion levels and creates ecosystems resilience.”

There are currently discussions with the organic asset manager Aquila – which has already converted many conventional farms in New Zealand – about managing the farm conversions on the ground.

Stancu adds that as experience with execution is gained, other revenue streams and options such as land leasing will be looked at, in addition to current models for land purchases.

Potential returns

The type of investor that would be a good fit for the project also took time to uncover. Law changes in New Zealand have dramatically reduced the ability of foreign entities to own land, particularly farmland.

“That left New Zealand’s pension funds,” says Bradly. “And what they wanted was debt and at scale.”

This has dictated the type of financing that may work best. The current proposal is for a $100 million-plus, 10- to 15-year bond, paying a 4% to 5% coupon with an equity component that provides for an upside to bondholders from capital gains made when the 7,000 hectares of land are eventually sold. It is made sweeter because New Zealand does not have capital gains tax.

“If you look at the potential returns compared to a green bond, it’s very attractive,” says Bradly.

While the project has some way to go, Bradly is confident it can happen.

“Conditions have never been better. The regional government wants to do something to improve water quality and the environment. It knows agriculture is the key, but it doesn’t know how to do it, so is looking for partners. We have farms on sale because of ageing populations of farmers and pressure to change farm practices or because banks have withdrawn lending. And we have a lot of investment money re-orienting to climate.”

Regenerative practices

In the US, investments in regenerative agriculture are slowly increasing as the country is under scrutiny as the world’s largest producer of corn, soy and beef, and among the top four for cotton and wheat.

In July, the Soil Wealth Report financed by the US Department of Agriculture and the Natural Resources Conservation Service was published. It sought to uncover how private finance could be brought into regenerative agriculture in the US by assessing the current investor landscape.

The report, conducted by the Croatan Institute, the Delta Institute and the Organic Agriculture Revitalization Strategy, showed that of the $321.1 billion of US-focused investable sustainable agriculture strategies, about $47.5 billion is invested in strategies including one or more criteria related to regenerative agriculture.

But the authors estimate that $700 billion will be needed over the next 30 years to realize the carbon sequestration and climate mitigation potential associated with implementation of regenerative agricultural practices globally.

Of the current regenerative agriculture investments, farmland investments and real assets accounted for the lion’s share in the US, at $22.8 billion. Like the Waikato project, owning land is still seen as the least-risky option.

Private equity and venture capital account for $6.9 billion in investments, and here companies are weighing in with their own private funds. Patagonia, for example, which sells outdoor clothing and has a food and beverage arm called Patagonia Provisions, has its own in-house venture fund, Tin Shed Ventures. Phil Graves heads corporate development and Tin Shed Ventures for the firm.

“We’re all in for regenerative organic agriculture. We’ve provided debt and equity financing to farmers and ranchers actively using – or transitioning to – regenerative organic practices with our food and fibre supply chains,” says Graves.

One example is an investment in a buffalo ranch in South Dakota that produces grass-fed bison.

“Wild Idea Buffalo’s business model restores the Great Plains ecosystem and is the partner that supplies us with buffalo jerky,” Graves says. “Our capital enabled the company to take their regenerative practices to the next level, such as harvesting their bison on the prairie instead of trucking them to a slaughterhouse.”

Patagonia is also looking at how it can advance the Regenerative Organic Certification (ROC) programme it developed with the Rodale Institute and organic soaps producer, Dr Bronner’s.

“We need high-bar certifications, such as ROC, and better financing tools,” says Graves. “Governments and financial institutions cannot keep their heads in the sand by continuing to insure, subsidize and fund chemical farming operations that are harmful to human health and the environment.

“A common argument is that regenerative organic agriculture requires more land than is available to feed a growing global population due to inferior crop yields. This argument has decreasing relevance as recent studies show regenerative organic agriculture has similar yields to conventional.”

Effecting change

Public equity investing is also a possible means to effect change. Among regenerative agriculture investment vehicles, $8.4 billion is in public equity, according to the Soil Wealth Report.

Karianne Lancee, sustainable and impact investing research analyst at UBS Asset Management, says: “Large investors have been thinking about agriculture through an impact investment lens, such as using private equity investments to help the transition to sustainable and regenerative farming, but people have realized that a lot more investment is needed, and listed equities are part of the solution.”

UBS Asset Management has been working with large institutional investors, including Dutch pension fund PGGM, to create a fund that invests in themes of water scarcity, food security and supporting a sustainable farming system. They are working with three universities, Harvard Public School of Health, City University of New York and Wageningen in the Netherlands, to build an impact measurement framework.

UBS has also signed up to the Fairr initiative, which researches and identifies companies with material risks and opportunities related to intensive farming – particularly intensive livestock production.

UBS collaborates with other asset managers to examine shareholder engagement on risks and opportunities.

Lancee says engagement will be key if public equities are to be a force for transitioning farming systems: “Buying public equities alone just won’t cut it. Effecting change requires engaging companies to improve their business models, reduce risk and potentially increase a positive impact further than it might otherwise occur.”

That is what is so exciting. We can do it more easily than people think is possible, and it can happen faster than we think - Gabe Brown

Regenerative farming is simple solution to many of the world’s challenges.

“It has been a 25-plus year journey of learning about soil that never stops,” says farmer Brown. “I have come to the conclusion that no matter what ills we talk about – carbon, climate change mitigation, pollution of water resources, or a human health crisis like the one we have – all can be addressed by regenerative agriculture. That is what is so exciting, and we can do it more easily than people think is possible, and it can happen faster than we think.”

But transition is more complex.

Consumers must be prepared to pay more for food and clothes to reflect costs. Banks will have to adapt their financing models, while a greater appetite from the investment community is needed. Companies need greater transparency in their supply chains. Farmers will have to transition their practices. And governments will need to change their subsidy systems.

It’s no small feat, and the authors of the Soil Wealth Report suggest that multi-stakeholder collaborations are needed most for the transition to succeed. But the returns would be considerable, both environmentally and financially.

Research firm Project Drawdown, estimates that from the 108 million acres of current adoption, regenerative agriculture will increase to a total of one billion acres by 2050. Such an increase could result in a total reduction of 23.2 gigatonnes of carbon dioxide, from both sequestration and reduced emissions.

Regenerative agriculture alone – excluding other sustainable agricultural practices – could provide a $1.9 trillion financial return by 2050 on an investment of $57 billion. Regenerative agriculture expert Eric Toensmeier at Project Drawdown says the number one barrier to that conversion is, simply, finance.

Financing change in the cotton industry

Some 25% of all chemical insecticides produced in the world are used in cotton farming.

“There are ice cores in the Antarctic that have been found to have traces of cotton pesticides in them,” says Rhett Godfrey, co-founder of not-for-profit ChetCo, a coalition of organic farmers, brands and manufacturers.

In addition to the impact on ecosystems and the services they provide, in developing countries where conventional cotton is sprayed manually, poisoning is frequent, as are birth defects. Furthermore 90% of cotton is produced with genetically modified (GMO) seeds, which means farmers have to purchase more seeds after every harvest, putting them under financial stress.

In 2013 Godfrey began looking into the cotton supply chain to explore what was holding farmers back from making the transition to organic.

“The cost of transitioning and getting certified is high and it takes four years,” he says. “Smallholder farmers don’t have the resources to make that shift. And for more buyers to purchase organic cotton at the scale and traceability they require, we needed to bring together brands and manufacturers in coalition with growers.”

ChetCo helps farmers by purchasing non-GMO seeds, creating dedicated, long-term demand markets, aligning buying and growing schedules, sourcing brands and helping farmers get financing.

Godfrey says there is a large opportunity for impact investors and banks to step in and finance the working capital that small-holder producer groups need to buy cotton from their farmers. Coalitions such as ChetCo provide offtake market guarantees to de-risk loans, giving investors a safe and high impact investment opportunity.

“The finance needs of the farming community we work with, Chetna Organic, are about $5 million in working capital that we can return in just six to eight months – and we already have the long-term purchase agreements from suppliers,” says Godfrey. “The challenge is that traditional bank loans charge 15% on average. There’s an opportunity here to provide discounted lending to help organic farming communities become economically sustainable and to finance the move to organic cotton worldwide.”

ChetCo is preparing a blueprint for the Coalition of Private Investment in Conservation that demonstrates the elements required to create a financeable model to transition smallholders into regenerative practices using cotton as an example.

Rhett Godfrey and cotton workers. “Cost of transition is high”

Getting out of agrochemicals: India’s big shift

In Andhra Pradesh state in India there has been a natural farming revolution.

Started by Rythu Sadhikara Samstha (a not-for-profit organization owned by the Andhra Pradesh government) and now supported by international organizations including the United Nations Environment Programme, the World Agroforestry Centre and BNP Paribas, the Sustainable India Finance Facility (Siff) is designed to leverage private finance for public good.

The goal of the stakeholders is to eliminate reliance on agrochemicals to improve land resiliency and biodiversity, and save farmers from the debt-trap of spending money on inputs, and the government from the costs of input subsidies.

At its foundation lies a simple recipe: mix cow dung, urine, molasses and pulse flour. Leave outside for three days.

“It stinks to high heaven, but it works better than any chemical fertilizer, producing higher yields without depleting the soil,” says Pavan Sukhdev, president of the board of WWF International.

To prevent insects from damaging crops, lilac and green chilies are added to the mix and, to protect the soil, mulch is used.

Siff is working with stakeholders to facilitate an investment of $2.3 billion to help convert farmers to the Zero Budget Natural Farming (ZBNF) method. The money will be paid back by the cost savings of $900 million annually that the state spends on fertilizer and agrochemical subsidies.

“It will take five years to convert six million farmers,” says Satya Tripathi, UN assistant secretary-general. “With natural substances as inputs, their yields were better.”

So-named Master Farmers (many of them women) are then paid to train other farmers outside their communities in this method of farming. Now some 700,000 farmers have already transitioned to ZBNF.

When the project is completed eight million hectares will have been converted to ZBNF. And it doesn’t stop there. In early September, prime minister Narendra Modi announced that ZBNF would be implemented across India at the UN Convention to Combat Desertification Conference of Parties.

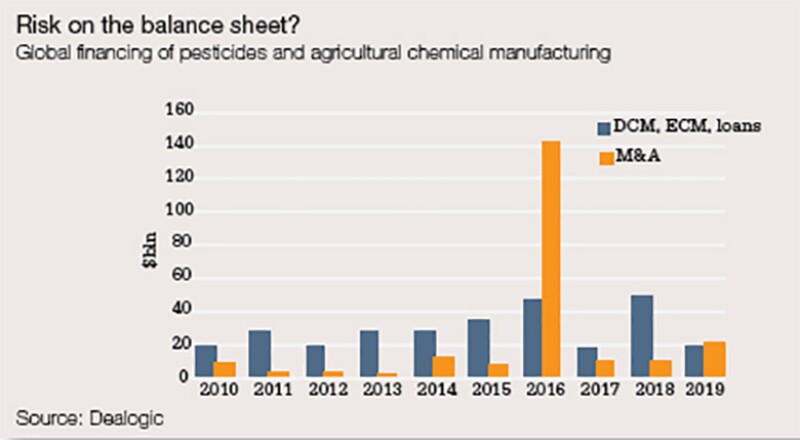

That such an enormous country could stop the use of agrochemicals underscores the risk that faces investors in and financers of agrochemical companies.

Last year almost $50 billion in finance was issued to pesticide and agrochemicals companies globally. When Indian finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman commented in June on a potential shift to ZBNF, the stock price of India’s largest agrochemical companies fell between 2% and 10%.

Bayer’s acquisition of Monsanto, producer of the agrochemical RoundUp, further highlights the risk to investors. Monsanto has faced a slew of law suits alleging that RoundUp has been responsible for health issues including cancer.

Bayer’s stock has dropped more than 30% since the acquisition was completed in June 2018. In September this year the German government exacerbated Bayer’s woes by announcing it plans to ban the use of glyphosates (used in RoundUp) by 2023.

Agtech has its own revolution

There’s not only a farming revolution taking place, but also an agriculture-technology revolution, according to Adrian Percy, an adviser for early stage companies and CTO of Finistere Ventures, a global technology and life sciences venture capital investor. Before his current role, Percy was the head of research and development for the crop science division of Bayer.

“Many think of agriculture as a not particularly innovative sector, but nothing could be further from the truth,” says Percy. “It is through innovation that we have managed to increase the effectiveness and efficiency of farming globally throughout many decades. The problem is that population surges, lack of available farmland and challenges such as climate change have now brought us to a breaking point. We need new thinking, tools and products.”

He points to technology that can help farmers apply inputs in a more specific and measured manner, using drones to apply small amounts of fertilizer or pesticides, for example. But agtech is not only about machines in fields, he says.

“There is vertical farming, growing food within urban areas to cut out transport, discovering microbes that can increase the healthiness of soil, plant-based diets and using biologicals to replace chemicals,” says Percy.

“In 2013, there was only about $500 million in venture capital money going into agtech annually. Now that’s about $2 billion and that will only increase as we address the challenge of how to increase food production on a decreasing land surface in the face of climate change and a need to protect our natural resources.”

Key numbers

Through land degradation, chiefly from using agrochemicals, the world has lost approximately 8% of total global soil carbon stocks (IPBES);

Between 25% and 30% of total greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions globally are attributable to food systems (IPCC);

15,499 species are under threat or have become extinct due to agriculture or aquaculture (IUCN);

In most high-income countries and many emerging economies, agricultural pollution is now the number one factor in the degradation of inland and coastal waters. (FAO);

Shifting to one billion acres farmed regeneratively could reduce CO2 emissions by 23.2 gigatonnes by 2050. (Project Drawdown);

To realize the carbon sequestration and climate mitigation potential associated with implementation of regenerative agricultural practices, more than $700 billion will be needed in estimated net capital expenditure over the next 30 years (Delta Institute).