Last year was a mild relief for many wealth managers. The positive returns of global stock markets (the S&P500 alone saw returns of more than 25%) provided a brief respite from the overall arc of slowing growth rates in wealth that was so much in evidence in 2018.

This year, however, wealth managers are not expecting markets or revenues to be as strong. Private bankers surveyed by Euromoney say they are less bullish on revenues in the year ahead than at any time since 2015. Continued fee compression, low interest rates and increasing spend on technology and talent, coupled with ever-present regulatory costs, are putting pressure on a business line that was seen by many universal banks as a revenue stream diversifier.

It is still an attractive business to be in, but it will be a challenging decade ahead – especially for those that do not have wealth management as their core business or, in the case of universal banks, those that have yet to connect wealth management to other business lines.

Euromoney interviewed those at the helm of the best global private banks and wealth managers as ranked in our 17th annual survey to find out where they see the growth opportunities and challenges for the years ahead.

“One of the biggest challenges right now is the opportunity cost of holding liquidity,” says Victor Matarranz, global head of Santander Wealth Management and Insurance. “Clients recognize holding cash has a negative cost in such a low interest-rate environment; and in Europe finding fixed income with returns above inflation means taking huge durations that many are not ready to take.”

The table stakes in wealth management today are having the skills in asset allocation and product knowledge but also the size and scale in technology - Mary Callahan Erdoes, JPMorgan Asset & Wealth Management

On the plus side for wealth managers, it means high net-worth clients are seeking advice on how to manage their investments in a way that meets the returns they need at a risk point they are comfortable with. It also means that the demand for alternative investments and more complex structures is increasing.

That is an opportunity that a number of managers point out. And if they have not done so already, they are now building their alternatives and real estate offerings.

|

Victor Matarranz, |

Matarranz says for his own firm that has meant hiring: “We have always been quite conservative with our clients and had a plain vanilla product set, but now we need specialized expertise around selecting best in real estate and private equity or private debt funds.”

For those that already help their clients move into private markets, performance has been bolstered. Vincent Lecomte, co-chief executive at BNP Paribas Wealth Management, highlights his firm’s focus on private equity and real estate in Germany as having had a positive impact on performance.

“It is important to diversify and seek out growth drivers,” he says.

And low interest rates are not just challenging for clients; having clients in cash or conservative allocations has become a drain on revenues for wealth management firms. With little sign of rates increasing soon, the key at the start of a new decade is to become more efficient and to do more with clients.

Engagement

In Euromoney’s survey of private bankers, one quarter think engagement with clients will be the biggest source of profits in the year ahead – more than in previous years. For Credit Suisse and UBS that route has begun with de-layering and getting closer to clients.

“Proximity to clients is going to be crucial in the years to come,” says Philipp Wehle, chief executive of International Wealth Management (IWM) at Credit Suisse, adding that the statement applies to all banking and not just wealth management.

IWM began applying a regional strategy in 2015, creating regional business areas with greater accountability and empowerment, which Wehle says amplifies the bank’s ability to identify clients’ needs and business opportunities.

That regionalization was further extended in 2018 when the division moved from a four- to a seven-region model.

Wehle adds that recently the business has been developing sub-regional strategies with dedicated measures to expand into markets that show attractive long-term growth prospects, such as sub-Saharan Africa.

|

| Philipp Wehle, Credit Suisse |

“The feedback is that clients are receiving increasingly bespoke solutions more readily from their regional advisers,” says Wehle.

It’s a strategy that UBS has also followed – creating regional and ultimately local autonomy to speed up decision making. There is little point having the power of a global platform if decisions aren’t being made at local level. It means becoming both global and local; something wealth managers have aimed for but struggled with in the past.

Few banks can claim to be important in each of the large markets of North America, Asia and Western Europe. Many retreated from these markets after the financial crisis – particularly the US – only to over-invest in Asia and then find their core European businesses failing.

As the wealthy have become more global in their businesses and family footprints, however, their need for advisers with global understanding has increased.

JPMorgan is one of the few banks with a global footprint.

“It’s just not possible to not have a global view,” says Mary Callahan Erdoes, chief executive of JPMorgan Asset & Wealth Management. “If you’re advising your client in Latin America on a local technology firm, but you don’t understand what is happening in Silicon Valley or in China, then you’re going to be giving poor advice.”

One of the leading concerns for client relationships in this industry is talent turnover. Growing internal talent is easy to say but hard to execute - Peter Charrington, Citi Private Bank

JPMorgan expanded its global footprint last year by becoming the first foreign firm to have a majority stake in a domestic Chinese asset management business.

Targeted regional expansion seems to be back on the agenda for the wealth management industry. Credit Suisse, for example, has been considering reopening wealth management in the US after exiting in 2015.

BNP Paribas and Santander have also both been expanding their wealth management offerings in the US (Santander ranks third in the US in Euromoney’s 2020 survey).

“It’s not that global beats local, but that you really need to be able to offer both,” says Matarranz. “You can offer the most sophisticated global products, but all clients need a current account, a credit card and financing. We’re one of few banks with a retail presence in 10 markets.”

He adds that Santander has been building up its wealth management business in certain countries, such as Brazil, and connecting all of its country divisions more closely so that clients are treated more holistically.

“You could have been a client in Spain and in the US,” he says, “yet the two businesses didn’t connect. Now that’s changed.”

Wehle also emphasizes integration: “You need a bank that can help you both navigate the regional or local network, and equally one that is integrated and international in its solution delivery.”

Domestic pressure

|

Mary Callahan |

As regional and global banks start acting more like local players, the pressure on country specific domestic wealth managers will increase. Up to now they have held their own. In Euromoney’s 2020 private banking and wealth survey, domestic wealth managers still dominate the top rankings in their countries.

BTG Pactual ranks first in Brazil, China Merchants Bank ranks first in China, KBC in Belgium, IFFL in India, Sberbank in Russia and KEB Hana Bank in Korea.

Where the larger banks have an edge is not just their global expertise, but that they tend to be part of institutions that also have large capital markets, investment banking and asset management businesses. That’s added value for the biggest growth market, entrepreneurs.

This segment is the focus for wealth managers for the coming years. Some 62% of private bankers surveyed by Euromoney say entrepreneurs offer the most growth for their firm. Family offices rank second.

Wehle says that firms that can serve clients holistically will likely be the winners in the years ahead.

“In the past, we saw businesses working more in silos, but today’s solutions often need to be integrated,” he says. “We need to conduct a holistic analysis of the clients’ assets and liabilities, and then provide access to our firm-wide experts and deliver tailored solutions. Having capabilities like investment banking and asset management is one important aspect, but it’s a further differentiating proposition when you can bring it all together for the individual client.”

He says this extends to non-financial services such as wealth transfer advice and next-generation wealth planning.

“Banking isn’t going to be just about financial services as the money transfers over the decade ahead,” notes Wehle.

At Citi Private Bank, chief executive Peter Charrington echoes Wehle’s view that leaders in wealth management will have to be able to bring to a client all the offerings from across the institution.

“Clients don’t want multiple contact points at one bank,” he says. “You need an adviser or a team of advisers that can navigate the entire company and who understand what we can and can’t deliver to a client. It’s not new or ground-breaking as an idea, but actually the execution can be challenging. You need company experts and advisers with a very broad knowledge and experience.”

It touches on another challenge wealth management chief executives see in the years ahead: talent.

“No two clients are the same,” says Erdoes. “And that means you have to really attract and retain those who have the expertise. It’s a highly competitive market. We’re constantly kept on our toes by competitors trying to hire our talent out. You need to ensure you’re one of the most highly compensating firms out there. But also you have to make sure your client advisers have high levels of productivity, so it’s about constantly investing in them and developing their skill sets.”

Some 54% of private bankers surveyed by Euromoney say they expect their firm to increase the number of advisers over the year ahead. That is a slight decrease from 2019, when 59% of bankers were expecting adviser headcount to go up. Investing in existing talent seems to be taking preference.

“You can’t just buy talent,” says Charrington. “You need to create your own organic model of producing talent.”

Citi Private Bank employs an apprenticeship model where junior specialists are nurtured by senior advisers.

“You learn on the job and senior advisers pass down their craft – and it really is a craft that needs to be appreciated,” he says.

|

Peter Charrington, |

Charrington says he expects wealth managers to apply greater focus on creating the right organic talent model: “One of the leading concerns for client relationships in this industry is talent turnover. Growing internal talent is easy to say but hard to execute.”

Erdoes points out that technology is going to determine firms’ abilities to attract and retain talent too.

“Advisers want to know that they’re driving a supersonic jet, not riding a bicycle,” she says.

It means investing in adviser workstations.

“It goes beyond having data on the top 10 stocks and who owns them to having the technology that presents you with every client you’ve ever spoken to about a single stock,” she says. “So when a buy or sell opportunity arises, there’s no time lost hunting around for which clients to speak with.”

Conversely wealth managers are looking for advisers with technology experience. Erdoes says there is something of a “war on data expertise” taking place. In response, JPMorgan offers coding classes to every person in the firm.

“If employees don’t understand how coding works, then they won’t be able to speak with their technologist to help them develop what they or their client needs,” she says. “This becomes incredibly important in a future world where banking will be half trading and half technology, and we need everyone speaking the same language.”

Last year, the firm ran a coding challenge for its employees around the world to see which cities could log the most hours of coding.

Technology

Technology investments are adding pressure to wealth managers’ already stressed earnings, but those investments are only going to grow in the decade ahead.

“The table stakes in wealth management today are having the skills in asset allocation and product knowledge but also the size and scale in technology,” says Erdoes.

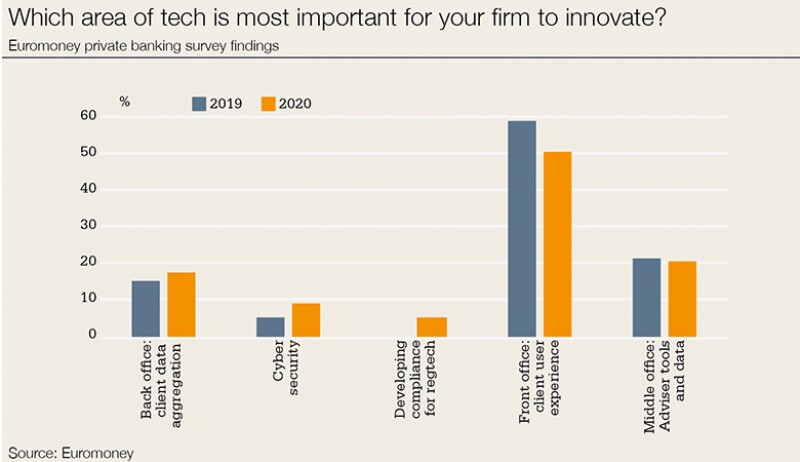

That investment in technology is from front to back. Euromoney’s survey respondents rank cybersecurity as having increasing importance.

Erdoes highlights the costs: “There are so many bad actors out there and the attacks are very hard to spot with a human eye alone. It’s not just about protecting the firm and its clients but also those we partner with, like law firms and accounting firms.

“We invest $11 billion in technology as a whole a year, $600 million of which is focused on the safety and security of our clients’ assets.”

UBS’s Asia Pacific COO, Wiwi Gutmannsbauer, has overseen much of the technology investment in the Global Wealth Management business in Apac. He says the costs are here to stay.

“It has not really changed over the last 20 years, despite people saying tech is now a huge spend,” he says. “It has been a big number and it’s going to stay a big number as regulation continues, client demands increase and disruption pressure is maintained.

“You have to keep up.” Client experience is still offered by private bankers as being the most important area within technology for innovation in 2020, however. The next wave appears to be the personalization of the digital experience.

Erdoes adds that over the next decade the big advances will be in the technological ability to take a client’s data and play it back to them in a helpful way.

“At the moment, client data is just informing us on how to serve them, but we need it to be able to help clients improve their own decision making,” she says.

She points to capabilities such as being able to measure yourself against your peers – not just in the returns of your portfolio but to better understand your relative financial health.

“There will be tools used in the decade to come that aren’t even thought of yet,” says Erdoes.

|

| António Simões, HSBC Global Private Banking |

When asked by Euromoney which technological developments would create the biggest change in the wealth management industry over the next five years, the majority of private bankers listed artificial intelligence, followed by blockchain.

Gutmannsbauer says there is a lot of excitement about AI, but the industry needs to be more thoughtful in how it uses it.

“It can’t be just about having AI manage a portfolio for clients or directly interacting with them,” he says. “Rather AI needs to help our advisers get closer to their clients.

“With 5G and the new version of WiFi and quantum computers, there will be a big door opening up that will give us as an industry so many more opportunities to improve the relationship between firm, adviser and client,” he adds.

Next to technology, another key differentiator in the next decade will be sustainable investments. Cesar Perez Ruiz is chief investment officer at Pictet Wealth Management. He describes sustainability as the biggest trend within asset management.

“I compare it to the Y2K discussions around analogue to digital,” he says. “If you didn’t make the shift and invest in digital, you suffered. It is the same here with sustainable investments. Even more so as regulation is arriving.”

He is referring to the EU’s second Markets in Financial Instruments Directive’s focus on suitability where environmental, social and governance preferences must be included within advice and product information.

Purpose matters to employees, clients and the bottom line, and we have a unique opportunity to encourage our clients to make a positive change in the world - António Simões, HSBC Global Private Banking

Many agree wealth managers will have to move beyond offering ESG funds and towards developing internal methodologies to help clients better understand the impact of their investment decisions on the environment and society across their entire portfolios.

Lecomte says the demand is there. A report on entrepreneurs that BNP Paribas conducts annually with Scorpio Partnership showed that “70% of entrepreneurs globally are more willing to invest sustainably than 18 months ago,” he says.

BNP Paribas has been one of the first movers in integrating sustainable investments across all of its offering. It launched its myImpact service last year in France, Luxembourg and the US, which is a digital tool designed with more than 100 clients to identify their impact preferences and priorities in line with the 17 United Nations Sustainable Development Goals.

“We can propose an investment strategy and a personalized philanthropic strategy in line with their personal values,” says Lecomte. This year the tool will be rolled out to clients in Italy, Poland and Belgium.

The firm is also progressively ranking mainstream products. “Our objective by the end of 2020 is that 100% of our recommended mutual fund universe will be rated, allowing wealth management to make its offering more sustainable and allowing clients to choose the sustainability level of their investments,” says Lecomte. “We are also ranking investment solutions across all asset classes, not just funds, to integrate sustainability in all dimensions of a portfolio. For instance, we integrated positive impact even in private equity with a KKR impact fund proposed to our clients last year.”

BNP Paribas Wealth Management manages €15 billion in sustainable mandates and funds, with a goal of €20 billion for 2020 that Lecomte says will be surpassed.

While there are a lot of data providers helping wealth managers make this journey to rating funds and companies, many firms are developing their own measurements. UBS, BNP Paribas, Santander and Pictet are among them.

“The ratings agencies will come with different views on the same company,” says Perez Ruiz. “Outsourcing metrics is going to leave you with mixed results.”

António Simões, chief executive of HSBC Global Private Banking, says sustainable investing at wealth managers is part of a bigger trend towards becoming “purpose-led”.

“Purpose matters to employees, clients and the bottom line, and we have a unique opportunity to encourage our clients to make a positive change in the world,” he says. “[That] can mean pursuing progress around climate change, financial or education inequality, or diversity.”

While Simões says that that can be material products or services, like a next-generations programme focused on sustainability or using its network to help fund environment-focused startups, it can’t always be articulated into strategy. Rather he describes it as a “motivation”.

He says his business has only just started the journey of becoming purpose-led, “and the corporate world has only just started to realize how important purpose is. It’s a trend to be watched.”

With such large investments in technology and entirely new product offerings, such as those in sustainability and alternatives, bankers say that now more than ever, wealth managers must be focused. According to data from Boston Consulting Group, the wealth management industry revenue margin has been steadily declining from 30.1 basis points in 2013 to 26.2 basis points in 2018.

“How are you going to absorb those costs? Not by being everything to everyone,” says Charrington. “We’ll likely see greater fee compression in the next five years, so you need to be very clear about your value proposition. There’s also likely to be consolidation as some private banks get their model wrong.”

It is the medium-sized players that may suffer – although the predicted M&A deals have not yet happened.

Without long-term focus, that continued downward pressure could become a distraction.

“Yes, there are pressures on revenues in this industry,” says Erdoes, “but if your client coverage teams focus on revenues, they’ve lost the plot because we’re managing people’s savings over decades. To plan for revenues ahead of client service would be the wrong way around.”