HOW COVID-19 WILL TRANSFORM THE FINANCIAL MARKETS |

| How does banking come back from this? |

| Loans: Crunch time for credit |

| Private equity bets on post-Covid survivors with hybrid capital |

| A stitch in time: can corporates follow bank resilience playbook? |

| Wealth managers find out who is with them |

| Life through a lens: bankers can do deals online, but can they win clients? |

| Home offices get a tech upgrade |

When US fashion retailer J.Crew filed for Chapter-11 bankruptcy protection on May 4, it was a stark illustration of how quickly the economic impact of Covid-19 would be felt in corporate America.

According to the US Department of Commerce, sales of clothing and accessories in the country fell by more than 50% in March, and the heavily leveraged brand was in no position to survive it. The firm has $1.7 billion of debt outstanding thanks – in a tale as old as time – to a $3 billion leveraged buyout by private equity firms TPG Capital and Leonard Green & Partners back in 2011.

J.Crew is not only a shopping mall staple across the US, however, it is also a poster child for the destruction of lender protections that a decade of ultra-low interest rates has produced and for what the consequences of that might be, as indebted firms struggle to come to terms with the new economic reality.

The clothing retailer spawned a new term in the loan market in 2016 when, keen to raise further cash, it transferred its brand name and other intellectual property into a new Cayman Islands-based entity that was beyond the reach of its creditors.

It did this through a legal process known as a trap door. The firm subsequently raised a further $300 million backed by these assets, leaving its existing lenders ‘J.Crew-ed’.

There was a sense of vulnerability heading into 2020, with it becoming likely that a global event could cause an economic recession. What we weren’t prepared for was the fact that it came on so quickly - John Redding, Eaton Vance

This notorious episode has come to exemplify the kind of borrower behaviour that became commonplace across leveraged finance after 2008. Similar asset transfers of intellectual property have been done by other highly indebted firms, such as Neiman Marcus and PetSmart.

Loan covenants have been weakened or have disappeared entirely across the market, and ebitda calculations have often been politely described as creative.

|

Jens Tomm, |

“Pre-crisis, some of the valuations and financing structures we were seeing looked very inflated and unrealistic,” says Jens Tomm, head of alternative asset manager ICG in Germany. “Liquidity was driving this, and it led to some structurings that shouldn’t have been done.”

This has led to vastly more senior debt in the market with a much smaller junior debt cushion to support it and can only mean higher defaults down the line.

J.Crew has now tapped its lenders again, understood to include Anchorage Capital and GSO Capital Partners, for $400 million debtor-in-possession financing, agreeing to convert around $1.6 billion of debt into equity as part of its restructuring.

Is this a foretaste of things to come?

Leveraged finance has long been seen as the flashpoint for the next crisis, but no one could have foreseen how ferocious the trigger would turn out to be.

The US market has ballooned to $1.2 trillion in size, 57% of which was trading as distressed levels (less than 80 cents on the dollar) in March, according to the S&P/LSTA Leveraged Loan Index.

That is a mindboggling $684 billion of distressed debt. For the week ending March 20, 95% of the index was trading below 90 cents on the dollar, compared with only 10% at the beginning of 2020.

The market had recovered sufficiently for the percentage of loans trading at distressed levels to have fallen to 20% in April – but that is still $240 billion, and a clear illustration of how jumpy investors are about this particular asset class.

“Market participants had suspected for years that we were late in the economic cycle,” points out John Redding, portfolio manager in Boston-based asset manager Eaton Vance’s floating-rate loan team. “There was a sense of vulnerability heading into 2020, with it becoming likely that a global event could cause an economic recession. What we weren’t prepared for was the fact that it came on so quickly.”

The big asset managers will be OK, but there is quite a long tail of people who have done things that maybe they shouldn’t - William Nicoll, M&G Investments

The damage had already been done. Sub-investment grade lenders must live with the consequences of the ever-weaker documentation and underwriting standards that had emerged before the virus.

How severe those consequences turn out to be will depend on the nature of the lender and where it sits in the capital stack.

“The big asset managers will be OK, but there is quite a long tail of people who have done things that maybe they shouldn’t,” points out William Nicoll, co-head of alternative credit at M&G Investments in London. “The ramifications for owners that bought assets they didn’t understand will be severe.”

In the first four months of this year 27 US loan issuers defaulted. Along with J.Crew these included JCPenney and Neiman Marcus, along with other household names such as Intelsat and Cirque du Soleil.

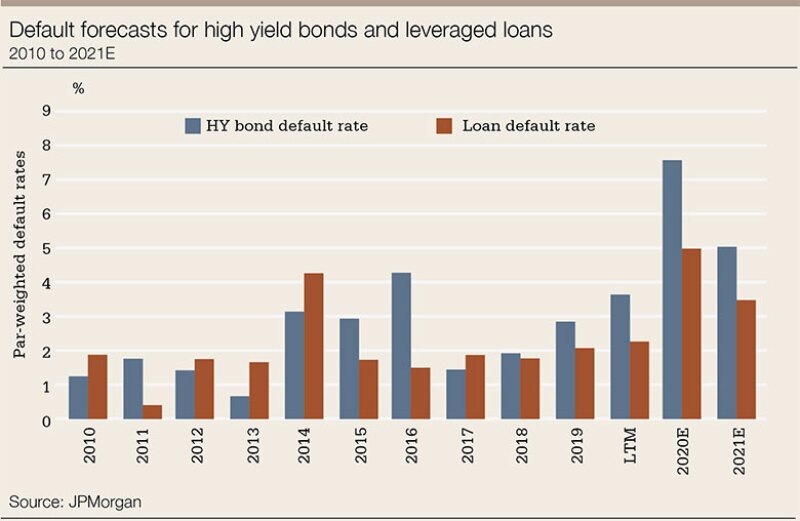

The defaults totalled $20 billion; analysts at JPMorgan now expect an additional $42 billion of defaulted loans by year end.

The bank points out that while default rates are rising, recoveries have been declining and now stand at 45.82% for first-lien loans, compared with a 22-year average of 65.56%.

“In the dot.com crisis of 2001/02 there was a 10% per annum default rate and 40% to 60% recoveries on secured high-yield credit,” says James Finkel, managing director in the disputes practice at Duff & Phelps in New York. “That may be a dream scenario for this go around.”

In the three months to April 17 the S&P European Leveraged Loan Index (ELLI) recorded 51 downgrades and only one upgrade; the percentage of B- and triple-C rated deals in the ELLI has risen to 21.5% – the highest level since 2012. Triple-C deals were at a six-year high of 5.4%.

In the US the percentage of triple-C rated loans held by collateralized loan obligations (CLOs) has now tripled to 12% and, according to Bank of America, 21% of outstanding CLOs have failed at least one overcollateralization [the extent to which the value of the assets in the pool exceeds the value of the bonds issued against them] test.

How severely loan investors will be damaged by this crisis depends not only on what they have bought but also how they have bought it. Many assets – around $600 billion – are now sitting in CLOs, which have attracted intense scrutiny as the speed and scale of potential corporate defaults becomes apparent.

Management teams want to be prudent. This is rainy day liquidity, so you don’t need a five-year deal - Charlotte Conlan, BNP Paribas

The US CLO market is now $691 billion in size.

These vehicles were the great survivors of the 2008 crisis, emerging largely intact as the collateralized debt obligation (CDO) market collapsed around them. But this time they are in the eye of the storm.

“Although CLO values were hit in 2008 with the contagion from the distress in ABS [asset-backed securities] CDOs,” says Finkel, “the loan collateral behind CLOs has never been viewed as being compromised at origination in the way that sub-prime mortgages were.

“The question is whether CLO noteholders below triple-A will get hit with actual principal impairments,” he says. “Historically, double-A’s never did and single A’s rarely did, but this is a different situation. There is more fundamental credit risk on the horizon than we have ever had before.”

Paradoxically, the loose structuring and weak covenants in the leveraged loan market could actually postpone default pressure on CLOs, and the idea that triple-A CLO notes could be hit still remains fanciful. But the sense of foreboding among investors is palpable.

“With CLOs you have all of the misalignment of interest that you had with RMBS [residential mortgage-backed securities],” insists Dan Zwirn, CIO at New York-based special situations firm Arena Investors. “The wheels of that machine have been really greased in the last couple of years.

“Is this a re-run of 2008? Given the moral hazard and underlying motivations, absolutely. This will be long and bloody because covenants are so crappy.”

Investment grade

This is a world away from the investment grade lending market, where business continued almost as usual when the Covid-19 crisis accelerated in mid March.

|

Charlotte Conlan, |

“We were taking underwriting risk on investment grade loans before the bond market restarted,” recalls Charlotte Conlan, head of loan syndicate and deputy head of leveraged finance capital markets at BNP Paribas in London.

“We have placed deals for high-quality businesses with strong relationship bank syndicates,” she told Euromoney in mid April. “The vast majority have been for 18 months to two years duration. Management teams want to be prudent. This is rainy day liquidity, so you don’t need a five-year deal.”

April saw large loan deals in Europe for Shell ($12 billion) and BP’s $10 billion two-year revolver via BNP Paribas.

In the US, corporate entities drew down $215 billion on their revolving credit lines between March 5 and April 9, according to LCD. Firms in the consumer discretionary sector accounted for 49% of this total, and 44% was drawn down by firms rated triple-B.

The market is still adjusting.

“There was a time in mid March when it was apocalyptic and there was no new issuance,” says Hamed Faquiryan, vice-president, multi-asset class research at MSCI in New York. “You would expect the shock to hit and the market to adjust; now the shock hits and a whole new world appears.

“Investment grade went from 100 to 400 basis points in two weeks – it is hard for anyone to wrap their head around what that means.”

The more you feed the flames of moral hazard, the harder the break is when it comes - Dan Zwirn, Arena Investors

For high-quality borrowers, the cost of borrowing may have risen, but these are relationships that the banks want to protect.

“The vast majority of banks are looking to be constructive,” says Conlan. “They are, however, focused on the quantum of exposure requested in a particular deal. For blue-chip clients, it isn’t a credit issue, it is a capital-allocation issue for banks. The vast majority of deals with large European corporates have been supported by both the large European and US banks.”

For sub-investment grade borrowers, however, it is most definitely a credit issue too.

Investment banks are exposed through not only syndicated lending but also the extensive warehouse facilities they have extended to CLO managers to enable them to ramp up new deals.

By late April roughly 20% of all loans held in CLOs had been downgraded and a further 1,000 tranches were put on review for downgrade. Many of these loans are also held in mutual funds.

|

John Redding, |

“It has been a challenge as we manage funds with daily redemptions,” says Redding at Eaton Vance.

“Late March and early April were a big test,” he adds. “It was tough, it was painful, but you do what you have got to do. It was a challenge coupled with the fact that the trader is working remotely and the dealer was working remotely. But there were buyers and that is what matters.

“Why were there still buyers? These are senior secured loans to large corporations that have an important reason to exist. That is what gave buyers confidence.”

The omens do not look good, however, and it is now up to these borrowers – and their private equity sponsors – to try to get ahead of the deluge of insolvency that seems inevitable.

But the nature of the buyer base, dominated by the CLO bid, will not make this any easier.

“The bond and loan markets are very different,” says Anthony Forshaw, head of capital markets, Europe, at Houlihan Lokey. “Loan market investors have a mechanical reliance on ratings, which we don’t necessarily see in the bond market. This helps the bond market to be more resilient than the loan market.”

Early response

In this crisis, the speed of the early response has been crucial in both financial and epidemiological terms.

“Some people have done the right things very quickly and had contingency plans in place – there is a smarter management set than there was in 2008/09,” observes Forshaw. “They will certainly have learned from the experience.

“There is always more staff turnover in investment banks, however, so there is an age band there that is a little directionless,” he points out. “We approached the market very quickly and put a deck on LinkedIn with six to eight various areas in which you should try to pull levers. We tried to engage with government departments to get assistance. The best advice for corporates was to get moving on your own.”

For many investors, the warnings had come early.

“We were getting early feedback from our portfolio companies where in some cases the authorities in China had shut factories at the end of January,” Tomm tells Euromoney.

Others quickly set to work figuring out just what the lockdowns meant for their portfolios.

“Once we all started working remotely, we put in place a red, green, yellow system to figure out which firms would be most directly impacted,” Redding explains. “We did that for the next six weeks and for the next six months – not just for revenue and turnover but for, most importantly, liquidity. That is all that matters in this situation: will the company run out of cash?”

Unfortunately, in many cases, the answer is yes.

For long-term capital, the bid to liquidate isn’t there. The context is that the central bank is likely to backstop every part of the market - Hamed Faquiryan, MSCI

How will lenders respond? Will banks take a different approach to that of institutional lenders? How will ratings-dependent CLOs impact workouts and restructurings? And how will the fast-expanding private debt funds behave?

On the latter, seemingly so far, so good.

“We have been pleasantly surprised by how supportive private debt funds have been,” says Forshaw at Houlihan Lokey. “Most of the big guys are ex-bankers and/or crisis veterans and know that there is limited upside in playing hard ball.”

Many institutional lenders and bankers seem to, so far, be taking the same view.

“Thus far, lockdown is being seen as a point in time,” explains Jeremy Duffy, partner at law firm White & Case in London. “Banks and direct lenders are cooperating and saying they do not want to take the keys.

“They would rather grant forbearance, financial covenant holidays and extensions. People have taken a view that this hopefully not extended period is extraordinary. They want to keep the lights on.”

One reason they want to do this is that lenders are all too aware of the protections that have been eroded over the last few years of lending excess. Weaker covenants will make it much harder for lenders to take action, even if they wanted to.

“Some cov-lite loans have more complicated – and potentially pernicious – features as financial sponsors have been able to insert provisions such as the ability to restate ebitda and equity cure rights,” says Finkel. “People are potentially in for a rude awakening when they try to enforce on these loans.”

Even if lenders are prepared to turn a blind eye to covenant breaches in the short term, this won’t go on for ever. So firms might get creative. The obvious place to start is with their ebitda calculations.

These have become looser and looser in recent years, along with the covenants themselves. WeWork’s famous ‘community ebitda’ stunt in its 2018 debut high-yield bond issue saw an adjusted ebitda of negative $193 million transformed into a positive community-adjusted ebitda of $233 million through the miracle of ignoring its sales costs.

Firms will now be doing all they can to prop up their ebitda – although that is a tough challenge when revenues have evaporated.

“Ebitda will very likely fall,” says Duffy. “While corporates may have add-backs for extraordinary items associated with Covid-19, if the actual revenue isn’t there, then ebitda, which is the glue to many of the points of flexibility in the documentation, falls away.”

We have seen CLOs survive very protracted workouts of credits that went bad – just never this many - James Finkel, Duff & Phelps

One solution is to simply ignore reality and state your earnings as ebitdac – earnings before interest, tax, depreciation, amortization and coronavirus. In other words, use what they should have been, not what they actually are. That seems a little reckless.

In Europe, Blackstone-owned German manufacturer Schenck Process is understood to have reduced its current leverage multiple by reporting it on this basis.

Another approach that sponsors and larger borrowers are taking is to ask the banks for covenant holidays based not on ebitda for the first and second quarters of 2020 but on the relevant quarter last year. It must be tempting to pretend that the last few months didn’t happen on both sides of the deal.

“We are very impressed at how helpful the debt markets are being with creditors,” Forshaw told Euromoney in April. “This is a human crisis, and even if something has covenants, they are being waived. A sensible, rational request for assistance will be well met and a temporary solution found.”

That will not last for ever.

“At some point, however, if you are not making your original revenues, even a covenant-lite deal has things that will trip in this environment and loan repayment deferrals may be harder,” Forshaw says, adding: “I think that good businesses will continue to get alleviation in the medium term. No bank is going to tank a company in three years’ time over support that it is being given now.”

|

Dan Zwirn, |

Unlike 2008, this is not a liquidity crisis. Although, as Zwirn points out, that is only “because these assets were materially underpriced and weakly structured. Two-months ago’s triple-Bs are 10-years ago’s double-Bs.”

Instead, it is a much more serious insolvency crisis.

But there are positives.

“Interest cover levels are better than they have been in the past crisis and liquidity levels are better too,” points out Stan Hartman, head of EMEA high yield and leveraged loan syndicate at BNP Paribas.

“In 2009, there was a general concern around liquidity within the financial system. Today consensus is that the banking system is sound and there is still an incredible amount of capital on the sidelines.”

That has obviously been helped by the swift actions of the central banks this time around.

“For long-term capital, the bid to liquidate isn’t there,” says MSCI’s Faquiryan. “The context is that the central bank is likely to backstop every part of the market.”

This feeds through to the private market as well.

“Historically the private market has used the public market as a proxy for pricing risk,” Nicoll at M&GI points out. “That becomes difficult if you have a public market that is completely distorted. A bounce-back in public markets is rational if you know that you have a buyer of last resort.”

The impact of this is clear in recent spread behaviour.

“There is dislocation or mispricing in debt markets,” Tomm observed in mid-April. “The better-known senior debt tranches dipped for 10 days but are all back to par now. The only sellers were small levered hedge funds, not banks.

“If you are trying to buy into a decent business, it is all back to par.”

Brutal process

Private equity firms are now going through the brutal process of deciding which of these decent businesses to support and which to let fail.

“From a present-value standpoint, you have lost three to six months of earnings,” says Hartman. “But if you are buying a good business with a strong moat, you should be OK. You don’t want to be in a marginal player in a marginal industry.”

Sponsors will help good companies through a short-term cash-flow crisis, but marginal businesses are much less likely to be saved.

“Clearly,” says Nicoll, “with many companies, if you don’t have any cash flow for two months, they will fall over, so rational PE sponsors will therefore put money in. But if you have a relatively unattractive business to start with and you are relying on leverage to make the return, then it simply won’t work.”

As defaults at these borrowers accelerate, will the damage in the CLO market be as bad as feared?

|

Hamed Faquiryan, |

“The Fed is accepting triple-A CLOs for short-term collateral repo, which gives large institutional holders liquidity but may not create price support for triple-C loans,” says Faquiryan.

CLOs have a lot more flexibility to hold triple-C assets than they did, but these loans will only deteriorate as protracted debt-for-equity exchanges are negotiated. Underspending on capex at struggling firms (starkly described by JPMorgan analysts as “burning the furniture”) will hit not only the cash flow to the structure but also any recovery value from the loan itself.

Nashville-based medical staffing firm Envision, whose $5.4 billion term loan is now part of a proposed debt swap at the KKR-owned company, is one of the top 10 most held issuers in US CLOs (the most-held being heavily indebted telecoms conglomerate Altice, followed by TransDigm and then Altice US). The loan was trading at 70c on the dollar in early May and has been downgraded to triple-C.

As more and more loans such as this are downgraded to triple-C, CLOs will start to breach the 7.5% buckets in their structure for such assets. This will hit the value of the portfolio, meaning that the overcollateralization test fails and payments in the waterfall start to get turned off.

This will hit CLO equity first, but then gradually work its way up the capital stack as the situation deteriorates.

According to Bank of America, 40% of all triple-B rated CLO tranches in the US are held by insurance companies. Some new CLO structures, called enhanced CLOs, allow for much larger triple-C buckets, but they are a tiny fraction of the broader market.

“CLOs are a much different product and in a much different stage now than they were in 2008,” Finkel maintains. “Due to many new issues last year, managers that will have some dry powder in CLOs have a long runway to reinvest at optimal levels. However, that dry powder is limited to cash on hand and returns of capital from refinancings, both of which may be limited.”

CLOs are, like any structured product, utterly reliant on ratings. Even if the structures can survive high default levels, they will still need to maintain sufficient asset quality in the pool in a very stressed loan environment.

“The larger issue is the widening ‘gap’ to recover from overcollateralization test breaches,” says Finkel, “Given low carrying values of triple-Cs and recovery values for defaulting assets, CLO managers may have to try to dig themselves out of the gap with a teaspoon, when they really need a shovel.”

The S&P/LSTA US leveraged loan price index was trading at around 2,279 in mid February, but had slumped to 1,766 by March 23. On May 13, however, it was back at 2,135, down just 6.3% from pre-crisis levels.

There are, however, still opportunities for CLO and other loan buyers to pick up good credits from the dislocation. Nicoll at M&G advised caution amid the volatile environment in late April.

“I think it is very difficult to know if you are bottom fishing if you don’t know what the price should be,” he said. “It could be argued that investors do not have enough information to invest in anything other than big investment-grade corporates.”

Big unknown

The big unknown at this point is just how bad loan recoveries will be this time around, given the almost total absence of covenants in loan documentation.

Euromoney has written before about the ways in which credit opportunity funds may seek to use what covenants there are in a corporate’s funding mix to trigger an outcome in another part of the financing structure – in particular the springing covenants that are still in place in revolving credit facilities (RCFs).

Investors in term loan Bs (institutional loans to sub-investment grade borrowers) would benefit from the cross-acceleration of the RCF, so it would make sense for investors in the former to push for this.

The leveraged loan market has long been living on borrowed time. The existential question it now faces is whether or not the unprecedented economic damage that Covid-19 has wrought will result in the wave of loan defaults that many are now predicting.

The good news is that ultra-low interest rates are here to stay and that the central banks have unquestionably done what they can this time.

“The government has come out very aggressively against water finding its own level in terms of asset and credit pricing,” says Zwirn. “The more you feed the flames of moral hazard, the harder the break is when it comes. In 2008, you knew that ground zero was concentrated in 10 to 20 places. Now it is all over the place.”

Concern over the vulnerability of many CLOs is well founded. These vehicles could be the Achilles’ heel of the market in the weeks and months ahead. Hartman at BNP Paribas insists that while “CLOs are under a lot of pressure from a ratings perspective, arb-driven market-static structures probably work, and the market will come back eventually.”

It is a question of just how long it takes for this process to work its way through a market that has enjoyed such stellar growth, a market that has been the rocket fuel of the cheap debt-fuelled excesses of recent years.

“We have seen CLOs survive very protracted workouts of credits that went bad – just never this many,” says Finkel. “It is just the scale of the problem and the mounting insolvencies which are likely to accelerate in the next three to four months and could take a very long time to work out.”