"Our call was for everybody. The debt trap is not just about China, it is a burden for our countries – it is about the global conditions, our dependence on raw material, our exporting and the large informal sector.”

Amani Abou-Zeid, the African Union’s commissioner for infrastructure and energy, is talking to Euromoney from Cairo. She speaks with palpable frustration about the way in which Chinese lending to Africa has been, as many see it, appropriated as part of a diplomatic discourse that pits an aggressive China intent on bankrupting Africa against a benevolent West.

“Stop treating Africa as if we are unable to govern ourselves. When you talk to us, talk to us about how we can partner with you – and in a faster way,” she says, echoing comments from Moussa Mahamat, chairman of the African Union commission in Vienna in 2018.

He said then: “Africa refuses to be the theatre for playing out of rivalries between Chinese, Americans or Europeans.”

Chinese lending to Africa has been thrown into focus by calls for relief on all official, multilateral and private-sector debt repayments, to free up essential fiscal space for African nations to tackle the health and economic crises caused by Covid-19.

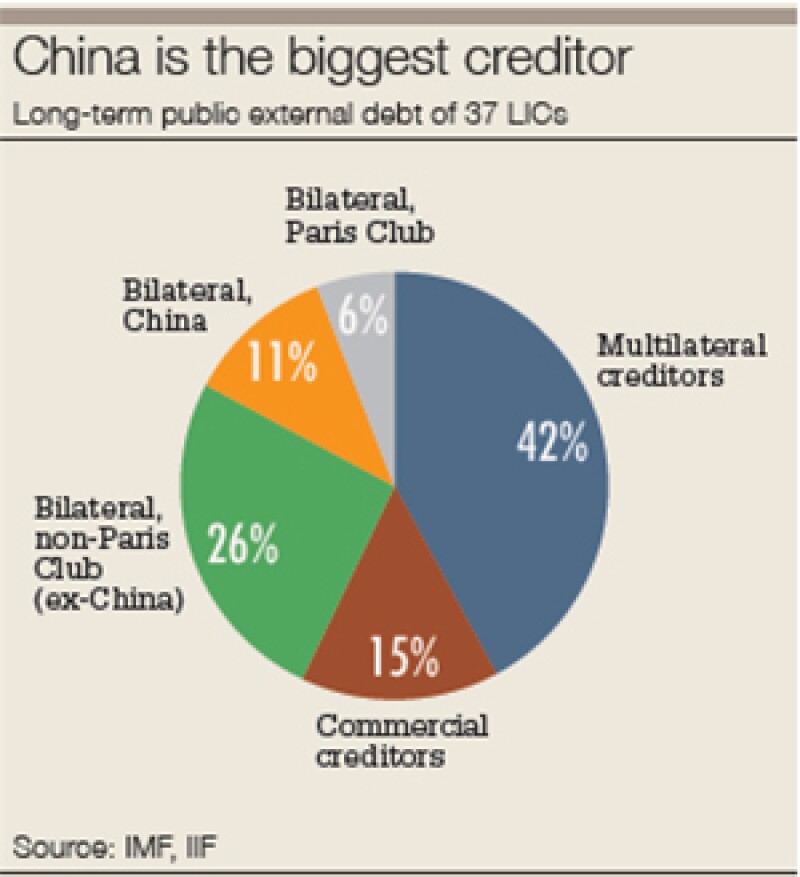

China is uniquely exposed to the economic slowdown in Africa, having emerged over the last few decades as the continent’s largest single creditor. Around 20% of all Africa debt is owed to China.

We have had bad experiences and good experiences with literally everybody, and everybody learns, including the Chinese - Amani Abou-Zeid, African Union

It is clear that China has a difficult balance to play between furthering its own international and commercial interests and being seen as a good actor on the world stage. Meanwhile, African stakeholders are keen to open debt discussions.

“Africa’s focus is about securing financial access to fund development for its fast-growing population,” says Abou-Zeid. “We need serious partners; we need people who can deliver. We have had bad experiences and good experiences with literally everybody; and everybody learns, including the Chinese.”

Both sides see the relationship as a long one. China’s president Xi Jinping singled out Africa for support in his address at the opening of 73rd World Health Assembly on May 18, reiterating his country’s commitment to the G20 Debt-Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI) and offering greater medical support to Africa.

African stakeholders are predicting that future relations will be less about big government-funded infrastructure projects – although these remain vital to African development – and more about greater economic integration, direct investment and ultimately a new wave of investment in technology.

Amani Abou-Zeid, African Union

Landmark step

The devastation of Covid-19 has led to calls for China to forgive loans to Africa, while the G20 has already agreed to suspend debt payments for low-income countries.

That agreement was seen as a landmark step because China also signed up to the standstill and to a new degree of transparency that forces any country applying for a standstill to report, in full, its obligations to other creditors.

But while China signed the pledge, it added caveats that would effectively exclude hundreds of large loans extended through its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). China’s state newspaper Global Times noted that preferential loans such as those by the Export-Import Bank of China (Eximbank), “are not applicable for debt relief.”

It is not clear how China will treat the demarcation between official and private-sector claims, which is particularly relevant to Africa, where much of China’s BRI lending has been done on commercial or near-commercial terms, as well as at state bank or state-owned enterprise level.

While China has not revealed the extent of its loans to Africa, the China-Africa Research Initiative team at Johns Hopkins University has tracked some 1,000 loans amounting to $152 billion, and extended to 49 African governments and SOEs between 2000 and 2018.

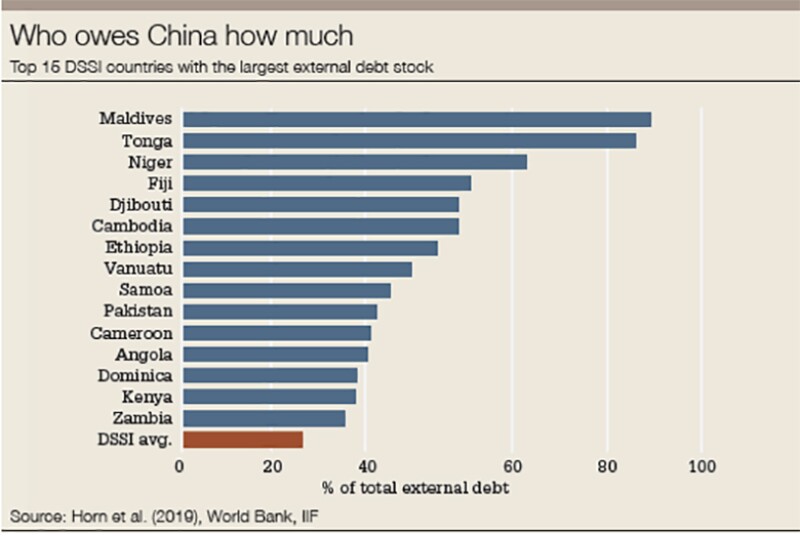

Under Xi’s flagship BRI strategy, $730 billion has been directed to overseas investment and construction contracts in over 112 countries. In Africa, this has led to a substantial build up of external debt in Djibouti, Ethiopia, Kenya and the Maldives.

Angola and Niger are also highly reliant on Chinese financing, according to the Institute of International Finance.

The twin shocks of Covid-19 and the collapse in oil prices have created a perfect storm for many African economies. The IMF is forecasting growth in sub-Saharan Africa to shrink by 1.6% in 2020, the lowest number for the region since at least 1970. Many economists say it could be much worse.

As the region’s single largest creditor, China is most exposed. Already facing problems of its own at home, Beijing will be keen to avoid a large wave of defaults on the money it is owed.

Instead it will opt for bilateral talks with creditors such as China to arrange rescheduling outside the G20’s DSSI. Analysts at Citi believe many countries will take this route instead of risking rating agency action and being cut off from debt markets.

As yet, it is unclear if any debtor countries have signed up to the G20 debt initiative. Kenya has said it will not because of the potential long-term impact of the conditionality associated with commercial debt.

Any concerns Beijing may have that African countries will band together to demand relief on their debt obligations are unlikely to be realized. China remains an essential player in Africa’s growth, and stakeholders are keen to maintain good relations between the two nations.

Over $143 billion was advanced to the continent for large-scale infrastructure projects between 2000 and 2017, while 17% of African governments’ external interest payments were paid to China in 2018, according to the Africa Finance Corporation (AFC).

Lungisa Fuzile, Standard Bank South Africa’s chief executive, tells Euromoney that while over-indebtedness is a problem in many African countries, China is not the only country to which African countries owe money.

|

Lungisa Fuzile, |

He notes that while forbearance of one kind or another is often the normal course of business, demanding debt relief on all obligations to China is not the right approach.

“If you have worked out that the debtor is experiencing a short-term problem, if you give them forbearance, they are likely to able to service your debt over a longer period of time,” he says. “History is littered with evidence where from time to time debt problems manifest and the lenders agree to come together to find a way to help the debtor.

“What wouldn’t be good is simply because people think that because China is a bigger lender to African countries, China is then expected to write off the debts and take the pain. That is not the way to do it.”

Ade Ayeyemi, chief executive of Ecobank Transnational, agrees that unilateral action by any borrower is not the right approach, and says that governments should work on a case-by-case basis based on agreements.

What wouldn’t be good is simply because people think that because China is a bigger lender to African countries, China is then expected to write off the debts and take the pain. That is not the way to do it - Lungisa Fuzile, Standard Bank South Africa

“As a banker, I would not tolerate unilateral action by my customers; therefore, governments should not knowingly access funding/capital with a promise of repayment and not repay,” he says.

“That Chinese capital is the savings of people in China,” he adds. “Every asset has a liability, they worked, they saved and they are using part of it to develop some of our own countries.

“People should restructure loans, offer new instruments and pay later. If you just say: ‘Well tough luck,’ the market has a very long memory. The savings in Africa are not sufficient to fund the investment that will be required to get Africa to where it still needs to be.”

Prevailing view

The prevailing view among those speaking to Euromoney is that China will be supportive of debt relief in African countries that ask for it.

“The Chinese have nearly always written off debt to Africa, and Africa fully expects them to write off almost all of it,” says Edward George, a former head of research at Ecobank who now runs Kleos Advisory. “I wouldn’t be surprised if China has already factored this in.”

There is a clear precedent for this. Researchers at Rhodium Group say that a number of recent renegotiations of BRI projects highlight the fact that concerns about these excessive debt burdens are legitimate, and that China has in fact already altered terms on around $50 billion of debt.

They have found 40 instances of debt renegotiations among 24 countries globally, most of which have occurred since 2007.

Abou-Zeid at the African Union says China has already taken an active approach to its obligations to Africa over the last year.

“I was in the forum on Africa-China Cooperation in 2018 with the president of China when he spoke about two things,” she says. “He spoke about debt forgiveness and he spoke about the trade balance between Africa and China.”

At the meeting Xi announced that all interest-free Chinese government loans to Africa’s least developed countries that have diplomatic relations with China will be written off.

In September last year, Ethiopia’s prime minister Abiy Ahmed announced China had agreed to extend the repayment period for some of the country’s loans from 10 to 30 years.

|

Samaila Zubairu, |

But full write-downs are not expected this time, partly because of the sheer volume of debt that may need to be renegotiated.

“China will seek to recoup the money bilaterally, but they’re a very timid creditor so will seek to kick the can down the road [rather than allow a default],” says Martyn Davies, managing director of emerging markets and Africa at Deloitte.

Davies advises multinational firms on their engagement in Africa, as well as advising regional governments.

He says that there is still naivety about the funding on the African side: “A lot think this money is free.”

AFC president and chief executive Samaila Zubairu says China will be supportive of bilateral discussions because of the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic and because it is in no one’s interest that a default occurs.

Cash-flow issues

The majority of Chinese lending has been funnelled into infrastructure projects, which are linked to economic prospects, and to industrial projects linked to the sale of commodities, so some cash-flow issues are inevitable.

“Some borrowers… will consider what cash flow they have for debt service versus what is required to stay afloat or provide for the health and economic crisis they face,” says Zubairu.

“There might be a conversation on extending the tenor, suspending payments for some time or reducing the cost for a certain period and recovering that in the future.”

But Zubairu says it very important that any negotiations are neutral in terms of net present value.

“Lenders shouldn’t lose money,” he says. “In some cases there may be write-downs, but I hope this doesn’t happen, as part of the challenge is access to financing.”

At the China-Africa summit in Beijing in 2018, China committed to set up a $10 billion special fund for development financing, reflecting China’s changing model of financial engagement in Africa, according to the Brookings Institution.

It says that China is moving away from the “resources for infrastructure” model and the next phase will be equity investment by a more diverse group of investors, supported by state development finance.

Several African stakeholders say that encouraging Chinese equity involvement is a good way to ensure projects are well developed and run to international standards.

Ecobank’s Ayeyemi is one of these.

“People should be willing to allow the lenders to participate in the management of the projects if they themselves are unable to manage it properly to regenerate repayment possibilities,” he says.

AFC’s Zubairu agrees that, in some cases, equity investments will make sense. The AFC itself is a borrower from China, and in 2018 signed a two-tranche $300 million loan from China Eximbank.

Chinese firms are also showing they have no desire to be short-termist in their approach to doing business with African partners, says Jeremy Stevens, Standard Bank’s chief China economist, based in Beijing.

China has quite a bit of attraction to small emerging-market countries, because of the benefits they have brought. But there is no free lunch - Atiq Rehman, Citi

Stevens says that his clients – mostly large Chinese corporates – recognize the difficulties their African partners are going through and are working to help them find financing solutions.

“That speaks volumes to the reality of the fact that Chinese corporates plan to be there for 30 to 40 years and are looking to how they can withstand this,” he says. “They are trying to be part of solution, whether that be trying to facilitate discussions between policymakers or helping shore up supply chains.”

|

Atiq Rehman, |

Atiq Rehman, head of Citi’s EMEA emerging markets business, says that while China will want to be part of the debt discussion and has a long-term strategy with BRI, it is too early to tell how the world will re-shape itself after Covid-19.

“It is a very different model to any other commercial model that you have in the world, and that is why China has quite a bit of attraction to small emerging-market countries, because of the benefits they have brought,” he says. “But there is no free lunch.”

Another thing African diplomats need to be aware of is that China’s strategy has changed and that they need to be realistic in their discussions, an adviser to both sides tells Euromoney.

“African diplomats are very naïve to what is happening in China,” the source says. “China isn’t trying to be everyone’s friend and give them all cheap sources of capital, and maybe they pay back or maybe they don’t. That is not how it happens at all.”

'Debt-trap diplomacy'

It is clear that for some countries, temporary relief or forbearance on loans will not be enough, while many of those who spoke to Euromoney dismissed concerns about Chinese so called ‘debt-trap diplomacy’.

The administration of US president Donald Trump is keen to promote the notion that China provides infrastructure funding to developing economies under opaque loan terms, only to strategically leverage the recipient country’s indebtedness for its own economic, military or political ends – or to seize its assets.

Ratings agency Moody’s warned in November of the risk that recipients of BRI cash would lose control of assets if they could not repay their debts: “Countries rich in natural resources, like Angola, Zambia, and Republic of the Congo, or with strategically important infrastructure, like ports or railways such as Kenya, are most vulnerable to the risk of losing control over important assets in negotiations with Chinese creditors.”

In recent years, media reports have suggested the port of Mombasa could be transferred to Chinese ownership over unpaid Kenyan debt after it was used as collateral for the billions loaned from China to construct the Mombasa-Nairobi railway in 2014. The government has refuted such claims.

Nonetheless, the topic has prompted much hysteria in the market, says Ecobank’s Ayeyemi, speaking to Euromoney via video link from Togo. His office overlooks the Port of Lomé, the deepest in West Africa and, before the coronavirus pandemic, the busiest.

About Lomé, he says of the Chinese partnership with the government of Togo: “They bring expertise, they bring capital and they work with the government to make sure the port works well.”

Ayeyemi is an advocate for the positive change China has brought to west Africa and the broader continent through its investment in roads and infrastructure. He says Chinese participation has increased economic activity and opportunities beyond what was thought possible.

But he knows this money does not come for free and says that, as a banker, he is fully aware that if the borrower does not pay back the loan, the project technically defaults to the lender.

“If I go to a bank in the UK and I take a mortgage and say I will repay over X period, and I default on the mortgage payment, what will the bank do? They will take the house,” he says.

However, Ayeyemi is quick to add that he does not expect China take control of projects in the way many critics fear.

Some of these fears stem from the reported grab by China of the port of Hambantota in Sri Lanka. The $1.3 billion Chinese-funded harbour was reported to have been handed wholesale to Beijing in 2017 after the island’s sovereign debts became untenable.

Many doubt the accuracy or simplicity of this story though.

“This seizure narrative has never happened,” says Paulo Gomes, co-founder of New African Capital Partners and co-chair of Afro-Champions, which mobilizes stakeholders to promote private-public partnerships for Africa’s integration and economic transformation.

Lender rethink

There is evidence to suggest that the funding for Africa’s mega projects may take a different form in the future. Not only is there a rethink by lenders, but Africa’s infrastructure market is changing, supported by the likes of the African Development Bank, AFC, development finance institutions and international investment firms.

Standard Bank’s Stevens says that there was already a shift in the way China intends to do business with Africa before the coronavirus crisis. Since 2015, he says, there has been a concerted effort from policymakers in Beijing to de-risk the financial system at home by cutting out and ameliorating the riskiest practices.

“For a company in China, if they are being told domestically that how you allocate capital is going to be far more scrutinized, it means the end of cheque-book diplomacy out of China,” he says.

African states spent $100.8 billion on infrastructure in 2018. Approximately 38% came from the African governments themselves, while 25.7% came from China. But investment levels were much lower in 2019, says Stevens.

“It is much more difficult to bring projects over the line. China has become increasingly commercial and risk aware about where it wants to do business, both in terms of market and sector.”

China is also said to be sensitive to the level of international criticism of projects such as that in Kenya.

China is looking at commercially viable transactions and not just government guarantees. They won’t reduce or retract lending, but they will be more cautious and will make sure they work with strong viable partners - Samaila Zubairu, Africa Finance Corporation

The AFC’s Zubairu agrees that the days of easy project funding are over, forcing governments to present better-planned, more economically viable projects.

“There is already a change in the approach to investments in Africa,” he says. “China is looking at commercially viable transactions and not just government guarantees. They won’t reduce or retract lending, but they will be more cautious and will make sure they work with strong viable partners.”

Many in Africa agree that the responsibility for better lending lies with both sides of an agreement.

While borrowers have in many cases lent recklessly, without ensuring the proper due diligence was carried out, governments also became profligate and careless with such easy money.

“Some projects have not gone very well and not performed as they should,” says Zubairu. “It is the twin responsibility of the borrower and the lender to structure sustainable transactions.

“If you put in place a proper process, proper engineering design and very rigorous supervision, you get a fairly good outcome. Chinese firms have the advantage of being cheaper and more experienced than most. The key success factor is in ensuring that the design and supervision is done well and by different unrelated parties.”

|

James Mwangi, |

Others argue that the less government involvement in projects, the better, and that the focus should be on developing a stronger private sector, and pursuing-deal making at this level.

Infrastructure experts say government money would be better spent upgrading existing infrastructure systems, or directed towards prioritising privatisation.

“If this sovereign debt by African countries is not repayable, it could be converted into equity, which would de facto force privatization,” says Deloitte’s Davies. “This could well be a positive outcome.”

James Mwangi, executive director and co-founder of global consultancy and Africa specialist Dalberg, says: “There is a particular lesson for Africa, which is you need to have a map of what you want your country to look like, and you need to weigh the different components of that map very clearly as you are going to the negotiations.”

Mwangi says he hopes that the debt and Covid-19 crises will have “burned away frivolous thinking” and that the formative experience of digging Africa out of the resultant economic mess will prompt policymakers to focus on responsible investing.

Push-back

Some countries have already started to push back on the terms of Chinese lending. Bagamoyo in Tanzania was going to be the biggest port in east Africa, but the agreement, signed in 2013 with China Merchants Holdings International, has stalled.

Deusdedit Kakoko, director general of the state-run Tanzania Ports Authority, told Reuters in May 2019: “The conditions that they have given us are commercially unviable. We said: ‘No, let’s meet halfway’.

“It would have been a loss... they shouldn’t treat us like school kids and act like our teachers.”

Although China accounts for a relatively small share of Tanzania’s external debt, Beijing has been among the largest investors in Tanzania in recent years. Tanzania owes around $2 billion to China, 9% of its total external debt, according to Standard Chartered research.

Several infrastructure investors told Euromoney that other players are entering the market, encouraging a more competitive and transparent bidding process.

Egypt’s Elswedey is building the Rufiji hydroelectic dam in Tanzania, while other companies such as Portuguese construction firm Mota-Engil have a strong presence.

In Uganda, several Turkish companies have opened manufacturing plants and other businesses, while the government is said to have drawn up a short list of companies from China, France, Portugal, Turkey, Austria and South Korea to begin work on its Kampala-Jinja smart motorway.

While some are predicting a retrenchment of overseas lending in the medium term as Beijing reconsiders its interests in Africa, others argue that the next wave of Chinese investment has only just begun.

“China has one of the healthiest economies, has a significant savings pool,” says Standard Bank’s Fuzile. “Additionally, it is already a lender to some of the African countries, but it might take more lending to alleviate the financial pressures faced by African countries.”

The first wave of Chinese investment can be defined as the post-independence era of the 1960s, when China began to build public buildings, railways and roads. The second wave in the 2000s really set the agenda for Chinese-Africa cooperation as money poured into large resource projects.

If you think about Africa’s longer-term trajectory… what needs to happen now is a deepening of ties with China - James Mwangi, Dalberg

George at Kleos Advisory says that the third wave was of smaller privately owned Chinese companies riding the coattails of big Chinese state-owned enterprises. He points out that there are some one million Chinese entrepreneurs living in Africa, running businesses without direct recourse back to China.

“Suddenly we are now talking foreign direct investment,” says Dalberg’s Mwangi. “’Come and build your business here’.

“If you think about Africa’s longer-term trajectory… what needs to happen now is a deepening of ties with China. Not just at government-to-government level, which can be problematic, but at business-to-business level.

“I hope that what we are seeing is this migration to a lower level, because that moves us from this world of massive closed government-to-government deals that often have a closed ecosystem of Chinese contractors and workers… to people starting businesses here, hiring and serving the local population.”

George says Africa is on the cusp of a fourth – digital – wave of Chinese investment – one that will only be accelerated by Covid-19.

Huawei already has a presence on the continent. One way or another China has provided almost the entire digital infrastructure on the continent, as well as cheap handsets.

There is already a pivot to tech in venture capital, China has recently made investments in Nigeria’s PalmPay, O-Pay and Lori Systems.

“They have built entire digital infrastructure, 70% of masts, 80% of handsets,” says George. “They are ready for the digital wave. They are going to come in. The suggestion that China is backing off is ridiculous. Covid will only speed up Chinese digitalization.”

Keeping Kenya on track

On May 12, the IMF raised Kenya’s risk of debt distress from moderate to high due to the impact of the coronavirus crisis.

The country was one of the first to sign a memorandum of understanding with China under its Belt and Road Initiative and has benefited from being a recipient of its funds.

Kenya owes $6.5 billion to China, 21.9% of its total external debt. It is already using a third of its revenue to service that borrowing.

Kenya’s standard gauge railway (SGR) connecting Mombasa to Nairobi – the biggest investment in Kenya since its independence – is a flagship BRI project in east Africa. It is also a textbook example of the kind of early BRI lending that is credited with fuelling budget deficits that pushed the nation’s debt to 61.7% of GDP at the end of last year, up from 50.2% at the end of 2015, according to the IMF – from a manageable debt level to a sustainability problem.

“If you look at debt-to-GDP ratios in a global context,” explains James Mwangi, executive director and co-founder of global consultancy and Africa specialist Dalberg, “it is not exactly clear to me that while African countries have become more indebted than they used to be, that they are on some obviously ruinous track if you look at the debt in isolation. The crucial caveat is: ‘what did you spend the money on?’”

Mwangi says that in a continent where the primary structural limits to competitiveness were a lack of infrastructure and a lack of capital investment, a surge of borrowing to finance investment was actually the only responsible course of action.

The problem, he says, has come from mismanagement of these projects on the ground.

“The issue is not that Africa borrowed heavily, the issue is that a lot of the borrowing went to consumption in the current account,” he says. “We still have overweight states, and there is some issue of leakage as well, but very few countries were thoughtful about which investments they were making.”

World Bank modelling suggests that the debt burdens associated with BRI will outweigh the growth effects for certain developing countries.

The SGR project has been blighted by allegations of graft, while there are concerns that the proceeds of the government’s Eurobond may not all have gone on capital expenditure.

“The capability it added was incremental rather than a transformative one, and more importantly, we left massive value on the table,” says one source close to the project. “Just getting a railway line to the Ethiopian border would have been transformative.

“Overall in hindsight, some people in government would say we did the wrong heavy capex to begin with, and there was an underestimation of how long this would take and an underestimation of the complexity,” the source adds.

Critics are quick to list numerous projects that they say have little prospect of generating the revenues required to repay them, or have fallen foul of government profiteering.

Scott Morris at the Center for Global Development says the lack of transparency around China’s financing model makes the system particularly vulnerable to corrupt practices.

“It also raises the risk that project costs will be inflated,” he says. “A virtue of competitive procurement is that it forces bidders to price competitively in order to win the contract. This model speaks to the motivation for Chinese overseas lending that, to a significant degree, seeks to employ domestic economic capacity abroad.”

Power for Guinea

In Guinea work is nearing completion on a 450-megawatt hydroelectric dam that is expected to nearly double Guinea’s power supply.

It is estimated that Guinea has one of the greatest potentials for hydroelectric power in west Africa, with a capacity of around 6,000MW yet to be developed. Only about a quarter of Guinea’s population has access to power.

The Souapiti dam is located on the Konkouré River near Conkary and is slated to open in October this year. Paid for by a $1.3 billion loan from Export-Import Bank of China, it is being constructed by China Three Gorges Corporation.

But what is unusual about the financing of the project is that it was partly paid for by selling a 51% equity stake in another dam to China Three Gorges.

Co-founder of New African Capital Partners and co-chair of Afro-Champions Paulo Gomes, who formerly worked for the ministry of finance, planning and trade in Guinea-Bissau, advised the government on this transaction and is an advocate of this model.

“In this whole discussion about Chinese debt we have to first start moving Chinese companies to provide equity more than debt, because they will have skin in the game,” he says.

The government brought together a team of Accury, a financial advisory and consulting firm, Rothschild, DLA Piper and Tractebel Engie to advise on the project.

Eximbank provided a $1.3 billion financing package at “concessional rates”, says Gomes.

Guinea’s reasons for choosing China as a financial partner echo those of many governments across the continent, explaining why it remains the partner of choice on many projects.

“It will have been very difficult and time consuming to ask for other sources, who would start asking if firms from their own country would be better placed [to construct and manage the project],” says Gomes. “You have a window of opportunity in terms of the lending, you want to deliver and you don’t want to be tangled into bureaucracy.”

The negotiations were tough, says Gomes, joking that there were no drinks in the pub afterwards.

What is unusual about the project is the China Three Gorges equity stake.

Encouraging greater Chinese participation may help to end the phenomenon whereby, once funding is secured, a Chinese contractor constructs the project and leaves. Development officials say this model limits any skills transfer or additional economic benefits to the local area.

In terms of debt sustainability, Guinea is considered a success story. In 2010 it completed its programme under the multilateral Heavily Indebted Poor Countries initiative. In 1998 external debt stood at 470% of GDP; by 2018, this had fallen to 38.5% of GDP in local currency terms, according to the IMF.