Chinese president Xi Jinping

In April 2019, analysts at Rhodium Group in Hong Kong sat down to assess the financial viability of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). What they found surprised them.

The second Belt and Road Forum had just wrapped up in Beijing and policymakers in the mainland and beyond were starting to voice their concerns. Western leaders feared that China was drowning the emerging world in general, and Africa in particular, in a new wave of debt.

Officials in Beijing pushed back against charges of ‘debt-trap diplomacy’, but they were beginning to stick.

China had internal reasons to fret. From the outset, the BRI was unpopular at home. Politicians branded it as a chance to reset the global order, but its people dismissed it as “too generous” to recipient countries, says Scott Morris, a senior fellow at the Center for Global Development (CGD), a Washington-based non-profit.

The project is huge.

RWR Advisory, a Washington-based consultancy, puts total lending to transport and energy projects from the Horn of Africa to central Asia since 2013, all under the BRI umbrella, at $461 billion. Direct loans to Africa alone between 2000 and 2017 are estimated by the China Africa Research Initiative at Johns Hopkins University at $143 billion.

|

Scott Morris, |

Still, what Rhodium expected to find was a snapshot of clear and coherent financial planning. What it found was the exact opposite. The image it depicts in its report is of a vast development initiative that wandered way off the rails and that is no longer fiscally sustainable.

It found evidence of China’s policy banks aggressively lending to fragile states, then rushing around in a desperate effort to plug holes in leaky budgets and extend, and often expand, credit lines.

Rhodium analysts found 40 restructured BRI loans with a market value of $50 billion, extended recently to governments and state agencies by China Development Bank (CDB) and Export-Import Bank of China (Eximbank).

In Africa, which dominates the data, it found 22 renegotiated loans worth $32 billion, although that number is probably higher, as much of China’s external lending is shrouded in secrecy.

“We suspect we are missing at least two dozen cases of debt forgiveness, especially to African countries,” wrote Rhodium.

By any measure it’s a startling number. It means at least a quarter of all Chinese lending to Africa has fallen into disrepair.

The consultancy uncovered a “wide variety of loan types”, including funding for specific projects (such as a railway in Ethiopia) and more general items (an unspecified credit line to Ghana disbursed by CDB). There were loans that funded budgetary items in Zimbabwe and state-run firms in Angola.

There were old loans (a $34 million loan to Cameroon written off in 2001) and newer ones, notably an $800 million credit line, still under renegotiation, to tiny Djibouti, a valuable staging post on the Maritime Silk Road, part of the BRI.

Rhodium found deferrals ($3.3 billion for Ethiopia in 2018) and refinancings ($21.4 billion for Angola, a key Chinese ally, in 2015), and several smallish write-offs. It warned: “The sheer volume of debt renegotiations points to legitimate concerns about the sustainability of China’s outbound lending.”

System shocks

It is possible China could have carried on in this vein for years. Total lending to African governments, firms and state agencies accounts for 7% of its external debt, valued at $2.06 trillion at the end of 2019 by China’s State Administration of Foreign Exchange (Safe). Even in the long term, that is manageable.

But that was before the intervention of two completely different events, both, in their own way, born in China. The first is the Belt and Road Initiative; the second the Covid-19 pandemic.

At its launch the BRI was a genuine shock to the system. It promised to redraw the trade and finance map in China’s image. In Beijing, the Party apparatus threw its weight behind the project – it had no choice, given that it was the brainchild of president Xi Jinping.

But it is increasingly clear there was precious little planning involved at the time.

Minxin Pei, professor of government at Claremont McKenna College in California, and a leading expert on Chinese governance, sees Xi’s grand idea to connect Beijing with Europe by land and sea, as “hubris and evidence of a lack of strategic thinking.”

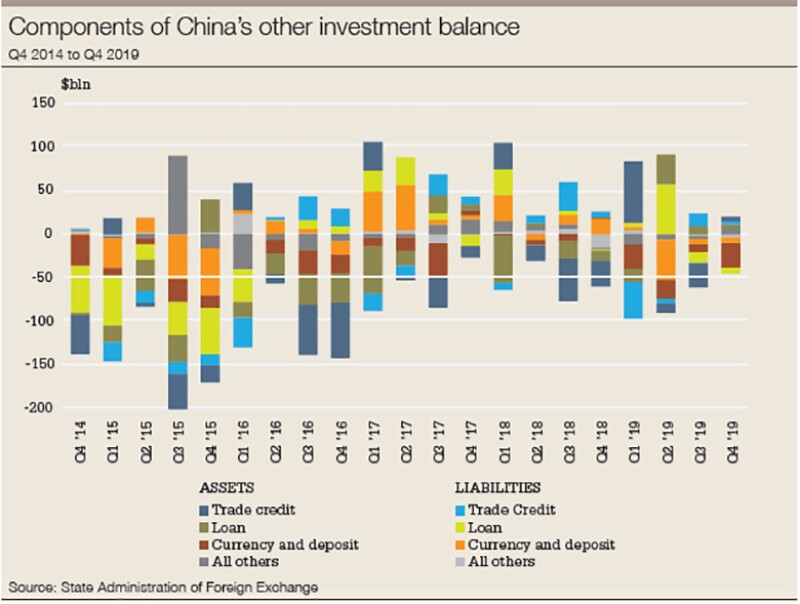

It resulted in a huge outflow of capital. Lending to 68 BRI countries, mainly in Africa and Asia, jumped sharply in 2015/16, with a second spike in 2018, according to data from Safe. That tallies with a sharp rise in Chinese external debt from $850 billion at the end of 2014, to $2 trillion five years later, according to CEIC Data.

It is now increasingly clear that at the height of this lending spree in the mid 2010s, Beijing: “had no idea how much was flowing out the door,” says Pei.

A Hong Kong-based banker says: “Even now, it is entirely possible that the government does not know how much it is owed or by whom.”

|

Lauren Johnston, |

A key problem is that some loans were extended not by the state or policy banks, but by private firms and state-owned enterprises to projects, companies and markets they happened to like. These are invisible to outsiders and almost certainly in some cases to Beijing itself.

In Africa, the advent of the BRI aggravated existing problems, as Beijing ramped up lending to countries that had little chance of meeting their obligations.

The region was always a bit of a belt and road outlier. In the 1970s, China saw it as a Cold War ally and itself as a saviour, funding projects that benefited both sides.

“It didn’t treat Africa as a charity – and that was appreciated,” says Lauren Johnston, an expert on Sino-African relations and research associate at the SOAS China Institute in London.

Notable facilities disbursed at the time include a Rmb988 million loan (then worth $400 million) to fund a railway linking Tanzania and Zambia. The two east African states faithfully paid the final instalment on the 40-year facility in 2013.

In Africa today China is everywhere you look. Mainland firms invested $72.2 billion in Africa between 2014 and 2018, according to data from EY. Beijing has financed an undersea cable stretching from Kenya to Yemen and a military base and a deep-water port in Djibouti. Both can be viably tagged as BRI projects. But most Chinese projects cannot.

“The BRI in Africa does not make much sense, at least in terms of its original aim,” says Pei. “Because Xi put his personal imprimatur on it, for years it became a grab-bag. So, if you wanted to raise money for something, you slapped a BRI label on it.”

The other problem is the scale of African indebtedness. The Overseas Development Institute, a London-based think tank, reckons China accounts for 10% of Nigeria’s external debt servicing. That share rises to 17% in Ethiopia, 33% in Kenya and 70% in Djibouti.

China didn’t treat Africa as a charity – and that was appreciated - Lauren Johnston, SOAS China Institute

China argues that its lending terms are favourable, although a CGD study found that weighted mean interest rates on loans to Africa by its policy banks are higher (at 4.14%) than World Bank loans (2.1%). Beijing also typically offers fewer grants and shorter grace periods on most loans.

This model jars with Western policymakers, who accuse CDB and Export-Import Bank of China of charging higher rates of interest on what is in effect low-cost and state-backed credit.

“It’s either a government loan or it’s not,” notes the CGD’s Morris. “Eximbank isn’t a commercial lender, it’s a government lender, so it should act that way.”

For its part, Beijing disputes the standard definition of what constitutes a sovereign or a concessional loan.

This is a technical point but a key one. By charging its policy banks with disbursing credit at slightly higher rates of interest, Beijing can tell itself it sees Africa as a commercial opportunity and not as a charity case.

One Hong Kong banker describes this outlook as deluded and self-defeating: “China sees the BRI as purely commercial, so it leads with its wallet and builds all this stuff, then is constantly surprised at Africa’s inability to repay.

“This goes round and round.”

Scaling back

Beijing’s approach also lets it portray its policy banks as just very large export credit agencies (ECAs). Eximbank is defined by ECA Watch, a global network of NGOs, as a financial institution that “facilitates the export and import” of Chinese-made goods. Yet this conveniently overlooks the issue of scale.

“Most ECAs are relatively small,” notes Morris. “Eximbank blows everyone out the water.”

There’s no denying this. In August 2019 Eximbank’s deputy governor, Xie Ping, said the bank had funded projects worth Rmb600 billion ($84 billion) in 46 African countries since its creation 25 years earlier.

Herbert Poenisch, former senior economist at the Bank for International Settlements, put total outstanding lending by Eximbank in all countries at $285 billion.

But all spending sprees have a limit and, even before Covid-19 struck, a reckoning was underway in Beijing.

Behind the scenes questions were being asked. Could it afford to continue to lend to – and prop up – poor African states? And if the BRI was unpopular, not just at home and in the West but also in the developing world, was China destroying its image?

The net result has been a quiet but consistent scaling back of lending to projects in all belt and road countries.

Because Xi put his personal imprimatur on it, for years it became a grab-bag. So, if you wanted to raise money for something, you slapped a BRI label on it - Minxin Pei, Claremont McKenna College

Net outbound lending has been negative since the start of 2019, says Logan Wright, director of China markets research at Rhodium Group. External debt has plateaued in recent quarters, while lending by mainland policy banks to Africa has dropped each year since peaking in 2016 at $29 billion.

Rhodium noted that project activity by mainland firms overseas was “decelerating before the Covid-19 outbreak”. Drawing on commerce ministry data, it says the number of overseas contracts signed by Chinese construction firms – a proxy for BRI-related lending – fell sharply in 2018.

This feeds into the growing sense of unease in Beijing that the BRI “got way out of control,” says the Hong Kong banker.

“Xi approved it and, before you knew it, China had lent $150 billion, $200 billion. By 2019, China had pretty much tapped out its ability to keep the process going.

“Beijing thought it had come up with a neat solution to fund BRI, by lending to developing countries in renminbi,” he adds. “Problem was, borrowers only wanted dollars. So, China wound up massively expanding its dollar-denominated external debt and creating just another dollar-based funding alternative for less-developed countries, akin to the World Bank. And that completely defeats the purpose.”

Then Covid hit. The pandemic puts China in a double bind. At home, it faces a sharp economic correction. Abroad, it is desperately fending off increasingly strident calls from indebted states to forgive some, or even all, of its loans.

Reticence

How it proceeds from here is unclear. In April, the G20, including China, said it would freeze all debt repayments for the world’s poorest countries until the end of 2020, marking the first time Beijing had participated in a global debt relief initiative.

But it stopped short of promising to forgive any of the debt owed by fragile nation states. It has also ruled out including in the G20 programme any of the distressed loans disbursed by Eximbank or CDB.

Its reticence is understandable. Germany’s Kiel Institute puts China’s lending to developing countries at $520 billion. All told, its outstanding debt claims amount to $5.5 trillion, according to data from the Institute of International Finance. That’s roughly 40% of GDP, a sum it could not write off even if it wanted to.

Beijing is under no illusion about the scratchy state of its external lending book.

“It knows it will face a number of write-downs that will hit its balance sheet,” says the CGD’s Morris. “It will try to kick the can down the road as long as possible, extending terms on specific loans if necessary. It will want to test this as a model.”

It’s not unlike the approach Beijing follows at home, where it ties itself in knots in an attempt to avoid having to deal directly with rising domestic debt.

This hold-your-nose approach to debt deferment is a favourite of the Party’s. When China forgives loans it often does so piecemeal and grudgingly.

In 2017, it wrote off $160 million in loans to Sudan – a sum that comprised just 2.5% of the country’s obligations to Beijing.

Often, it ties debt forgiveness to new lending. In 2018, it wrote off $7 million of Botswana’s debt. In return, the southern African state agreed to tap into a brand new $1 billion infrastructure facility.

|

Minxin Pei, |

So far, this model has worked. But Covid has changed the debate and Africa is getting antsy. In March its finance ministers called for debt owed by its poorest states to be written off or converted into long-term, low-interest loans.

Ghana’s finance minister, Ken Ofori-Atta, told China to “come on stronger” on debt, noting that African states, which owe China $8 billion in repayments in 2020 alone, cannot plan for the future until they know how Beijing will act.

Can China step up? Claremont McKenna’s Pei reckons the country is “stuck”. If it restructures or writes off foreign loans wholesale, it will stretch its finances and infuriate its citizens. On the other hand, if it demands full repayment of all obligations, it risks “antagonizing Africans and creating a global backlash.”

Calls for it to offer one-size-fits-all debt relief to poor nations are also likely to fall on deaf ears.

“China is very cautious about blanket agreements as it doesn’t know what kind of default problem there is out there,” says Rhodium’s Wright.

Pei points to two reasons it will shy away from blanket relief: “The first is a very negative domestic reaction at home. You would see uproar, with people asking why the Chinese government made such lousy decisions.”

Whereas, if it engages in separate bilateral negotiations, Beijing can keep the terms of each deal under wraps – “putting itself in a better bargaining position and increasing the goodwill it can earn with, and the leverage it has over, an individual country,” Pei says.

Morris at the CGD admits that in China’s eyes, this approach might seem “totally rational”. Fragile states facing a triple crisis of growth, jobs and debt “may want to see an offer of a debt write-down now,” he says. “The question for China is: does it know what the total fiscal cost would be?

“I suspect they don’t, they can’t see that number right now; so it makes sense to go loan by loan and country by country.”

Economic crisis

But logic may not be enough. The world faces the worst economic crisis in nearly a century.

In Africa, growth will disappear maybe for not one year but two. Morris says China’s nightmare scenario is “the realization that African debt cannot be ring-fenced. After years of lending, China now finds itself exposed globally.

“In such a fast-moving process, China may not have time to do a separate audit of 100 countries and work out which ones need write-downs and which do not. That’s just not going to be how it works,” he adds.

So far, China appears not to have a coherent answer to the problem. Writing off many billions of dollars of troubled loans offers it a chance to boost its credentials as a global leader.

But, as Pei notes, “goodwill is cheap. It evaporates tomorrow.”

He adds: “It is hard to see blanket debt forgiveness taking place.”

China is faced with difficult choices. It could pursue blanket debt relief or opt to call in most, if not all, of its loans. Both are unlikely, as is the prospect of it doubling down on Africa.

After years of lending, China now finds itself exposed globally - Scott Morris, Center for Global Development

“It cannot continue to throw money at a region that is poor and which offers very poor returns,” notes Pei.

The most likely outcome, says one Beijing-based analyst, is for China “to try to nickel-and-dime its way out of trouble – delaying loans for as long as possible and trying to avoid plunging the region into a real debt crisis. If Africa blows up, it is likely that China will need to recapitalize CDB and Eximbank.”

Then there’s the BRI itself. In an April 2020 research note titled ‘Booster or brake: Covid and the Belt and Road Initiative’, Rhodium Group said Beijing can maintain a high rate of lending – if wants to. Both of its policy banks “have enough political backing to bear the cost,” it said, adding that “playing saviour is cheap.”

But it added: “In light of the need for debt renegotiations, it is unlikely that Beijing will return to 2016/17 levels of new BRI commitments. That ship had sailed before the Covid crisis, and likely won’t return in the near future.”

Instead, it will focus on “dealing with debt renegotiations as best it can.”

Re-tooling the BRI

This is surely not what Xi had in mind when he unveiled his flagship foreign policy plan seven years ago. Retreat is a word rarely uttered by any Chinese leader.

Beijing has tasked Zou Jiayi, a capable technocrat and vice-minister at the finance ministry, with the job of re-tooling the BRI, making it more manageable and financially practical.

“Most of Zou’s colleagues, smart bureaucrats, don’t want to touch this issue – it’s a politically hot potato,” says one informed source. “But even when her colleagues were saying in public how great [the BRI] was, she was pointing out the debt risks were real and something the country needed to be aware of.”

This is not the end of the line for the BRI. Johnston at the SOAS China Institute says it “isn’t a 10- or 20-year plan but a longer outward journey. The point is to build bridges and conversations, utilize excess capacity [and] boost global development.”

In this context: “The risk of incurring balance-sheet losses should be weighed against those of avoiding them.”

To put it another way: nothing ventured, nothing gained.

There is however little doubt that the project’s global ambitions will be severely tempered in the near to medium term.

“There will be a major retrenchment,” says Pei. “You will see very few new projects announced. The viable ones will be funded, but the non-viable ones will be left alone, so you will see lot of uncompleted projects.”

Beijing is likely to tightly rein in lending to Africa. The same will be true of its policy lenders – although that doesn’t mean funding will completely dry up. Rhodium points to the chance for “new actors” to step in to fill the gap.

Highlighting the example of technology firm Huawei, it noted in April: “Much like they are now used at home to bridge financing gaps... Chinese firms could become new channels of Chinese funding to developing and emerging economies.”

The belt and road is not dead. One might politely describe it as resting. Just don’t expect Beijing to admit as much or to publicly state its desire to taper the project’s parameters. It is likely to become “lower-profile and more pragmatic and cautious,” says Pei.

“You’re going to see not clarity but messiness and fudging, with the aim of avoiding a massive default or a diplomatic disaster that will make the leadership look bad. In China, muddling through is a historic pattern.”