By Noah Sin

In the opening chapters of the Chinese classic, ‘The romance of the three kingdoms’, three warriors take an oath of fraternity and volunteer to defend the ruling – but quickly collapsing – Han dynasty against advancing peasant rebels. As the old order falls apart, the men go on to reign in one of the three kingdoms contesting for the right to govern China.

Asiamoney understands that no such oath was taken when the three Chinese officials who are now in charge of large parts of their country’s capital markets were put into their posts earlier this year. But it was no accident that they were, just like the three heroes in the story, called upon to save their country in the midst of an existential crisis.

This saga centres around Yi Gang, a US-trained economist-turned-governor of the central bank; Guo Shuqing, an iron-fisted regulator who strikes fear into bank and insurance bosses; and Liu He, China’s chief economic strategist, who was reportedly described as a “very important person” to president Xi Jinping, in Xi’s own words.

They face some challenging problems.

China’s Rmb250 trillion ($39 trillion) banking system is exposed to the shadow banking sector through off-balance sheet investment vehicles worth an estimated Rmb75 trillion, according to an April report by the IMF.

Shadow banking got a shot in the arm in 2011 when Xiang Junbo, who was head of the insurance watchdog at the time, turned compensation schemes into a financial market roulette.

“After Xiang Junbo took over as the China Insurance and Regulatory Commission’s (CIRC’s) chairman in 2011, there was a mini era of liberalization that got out of control,” says Brinton Scott, managing partner at Winston and Strawn’s Shanghai office, who focuses on the insurance sector. “Chinese investors flocked to universal life insurance products, which are actually investment products that promised returns as high as 8%.”

These so-called wealth management and shadow banking products provided between 29.8% and 31.7% of funding for net bond issuance in China in 2016, representing about Rmb4.5 trillion to Rmb4.8 trillion of capital, according to a February report by the Bank of International Settlements.

Xiang was dismissed in 2017 and subsequently charged with corruption.

As the wildfire spread, financial regulators were busy controlling the burn on their own turf and often failed to work with – or even talk to – each other.

One London-based banker at a bulge-bracket firm got a close view of this on a Beijing-bound business trip.

“A senior official at one of the regulatory commissions once asked me – note that I don’t speak Mandarin – to pass on a message to his counterpart at another regulator, in English,” says the banker.

Guo is the goalkeeper who ensures that regulations flow smoothly from the designing phase to the implementation stage - Tiecheng Yang, Han Kun Law Offices

The structure of the regulators contributed to the breakdown of communications. Since the establishment of the China Banking Regulatory Commission (CBRC) in 2003, the responsibilities for regulating financial markets in China have been divided between the CBRC, the CIRC, the China Securities Regulatory Commission and the People’s Bank of China.

Anthony Neoh, who served as chief adviser to the China Securities Regulatory Commission between 1998 and 2004, tells Asiamoney that this set-up presumed that insurers and other market players would stick to their own business lines, sowing the seeds of risk accumulation in the financial sector today.

“When we drafted these laws in the 1990s, we didn’t really think about these issues,” says Neoh, who was also chairman of Hong Kong’s Securities and Futures Commission between 1995 and 1998.

“We were mainly concerned about keeping capital flows in the respective sectors, like insurance and securities, which shouldn’t mix. But the world has moved on, and we should change with it too.”

Neoh’s view is shared by Ha Jiming, a senior research fellow at China Finance 40 Forum, a Beijing-based think tank that includes Yi, three People’s Bank of China deputy governors, a vice-chairman of the CSRC and a vice-finance minister.

Yi Gang, governor of the People’s Bank of China

While regulators were busy breathing down the necks of financial institutions, the business that these institutions engaged in quickly transcended sectors, says Ha.

“We have mixed operations in China. Banks could get involved in insurance business and insurers can lend,” he says. “But the regulations were drawn up with the assumption that operations are not mixed; that’s why we had one regulator for banks and another for insurers.”

Consolidate

Against this backdrop, what happened next seems inevitable. The banking and insurance regulators were merged in March to form the CBIRC, as part of an effort by Xi’s leadership to consolidate power across state institutions.

“Finance is the heart of modern economy. We must highly regard the need to prevent and control financial risk, and protect the financial security of our nation,” the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China said in a policy statement on March 21, detailing a reform package.

In theory, the merger should bolster the regulator, giving it an expanded remit. However, on the day the new commission came into being, it lost a key power – to draft regulations – to the PBoC.

This arrangement reflects the new division of labour, with the CBIRC under Guo in charge of microprudential supervision and the PBoC under Yi focusing on the macroprudential, according to Neoh. He sees this as a natural next step in the evolution of the Chinese regulatory regime.

“Most of what the banks are lending comes from deposits, and the growth in deposits essentially represents M2 growth in China,” he says. “Banks are closely linked with monetary policy. The supervision of the two cannot be separated.”

To Tiecheng Yang, partner at Han Kun Law Offices, who specializes in capital markets, this represents an even more radical shift: the splitting of responsibilities for financial regulations and monetary policy.

There were few signs of this storm coming. Not many analysts had put their money on Yi becoming the next governor because it was rumoured that Liu He would take the top job at the central bank. But an even bigger surprise came when, days after Yi’s new role, Guo was appointed party secretary at the PBoC, which, in China’s hierarchy, means he out ranks Yi — despite the fact that Guo’s other job as the inaugural CBIRC’s chief should rank below Yi’s.

Guo Shuqing, chair of the China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission

“Guo is the goalkeeper who ensures that regulations flow smoothly from the designing phase to the implementation stage,” says Yang. “Few at the PBoC, not even the governor, would know the financial regulations on a working level better than Guo, given his experience in this field.”

In fact, Guo is so uniquely qualified that he is probably the only official fit for filling the dual role. This could be as much an asset as it is a liability, says Yang.

“The intention is good. The question is: can it really work?

“This [having the same person in both jobs] is not the best way to avoid conflict of interest,” he adds. “But we don’t have another candidate like Guo who can guide the two institutions to work together. In future, when the right person emerges, he or she will take on one of the posts currently held by Guo.”

Notably, the securities watchdog is left out of the picture. But the idea of creating a super regulator by mashing all three commissions together, which was floated by some in the market in recent years, would have been counter-intuitive, says Alexious Lee, head of China capital access at CLSA.

“The key difference is that CBIRC oversees the money managers in the system, and the CSRC manages the pools which various players can put their money into,” he says. “You can track and control the money flows by merging the banking and insurance regulators. You don’t need the securities regulator to do that.”

FSDC’s job is to figure out what China should do as the global financial system evolves - Alexious Lee, CLSA

Furthermore, says Ha, while these regulators all have risk prevention as their top priority, they have different approaches to regulating financial markets. The CSRC is mainly focused on disclosure – it curtails risks by getting market participants to disclose as much as possible, whereas the CBIRC regulates through requirements, by asking institutions to comply with various risk-aversion measures.

But there is a cost, too, in sparing the CSRC from the merger. An industry source who has been advocating reform in the onshore bond market shares his frustration on the missed opportunity to capture the CSRC with Asiamoney.

“Bonds listed on the exchanges, for instance, are regulated by the CSRC,” he says. “If there are disagreements on our proposals between the CSRC and CBIRC, or between the PBoC and the CSRC, then we’re back to square one. The problem is still there and the merger does not even begin to address it.”

There is also a contradiction at the heart of this arrangement, as Yang points out. If the goal is to make implementation more effective, by separating the executor and the author of regulations, then why excuse one regulator from this requirement?

“The elephant in the room is that the CSRC still maintains both powers,” he says. “The same principle has not been applied across the board.”

New era

With or without the CSRC, there is no doubt that the CBIRC merger, along with the dual chief appointments of Guo and Yi at the PBoC, have ushered in a new era for China’s financial regulatory regime. Yet, around the world, business often carries on as usual despite new leadership, in the public as well as the private sector. How different will things be in China?

While Yi is renowned for his overseas experience (he got his PhD in economics at the University of Illinois in 1980s and then taught for eight years at Indiana University), he has been at the central bank since 1997 and deputy governor since 2007.

Guo is just as much an establishment figure. He spent four years as deputy governor of the PBoC in the early 2000s, before being appointed as head of China Construction Bank, governor of Shandong province, and head of the CSRC and the CBRC.

The choice of personnel shows that China’s leaders prefer more of the same, says Lee.

“These are not new players,” he says. “Yi’s appointment shows that there will be a continuation of monetary policy in China. After all, he was one of the architects of the current policy.”

Ha says that while their thinking is in line with that of their predecessors, putting them on the same team would create new synergies.

“Yi is a fitting choice,” he says. “He’s got a great understanding of international norms, having researched and taught abroad for years. That and Guo’s standing in domestic politics will work very well together as they try to alleviate risk in the domestic market and at the same time, open it up further to foreign market participants.”

Although Yi and Guo are instrumental in policy implementation, only the third man in this trinity will have the final word in setting the framework for such policies.

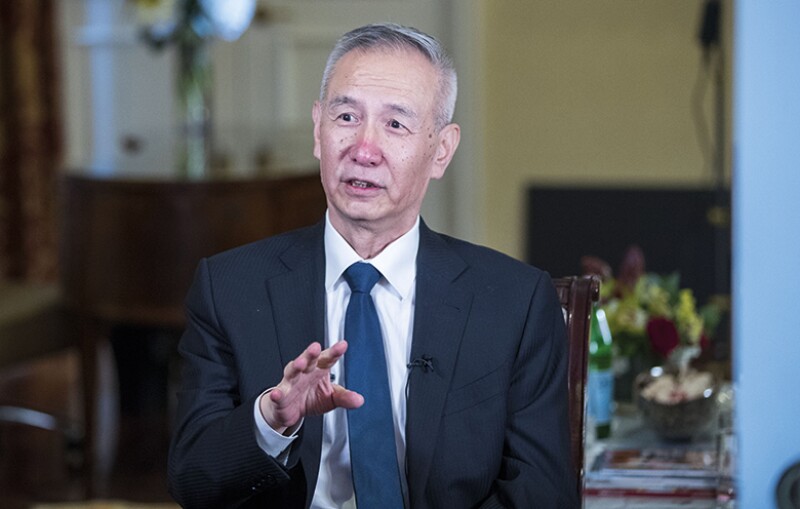

Liu He is a confidant and contemporary of Xi Jinping; he rose through the ranks to become vice-premier in March. He has been sent to cut a deal with the US amid escalating trade tensions, cementing his reputation as the chief economic tsar in the Xi administration.

Liu He, director of the Central Finance and Economic Affairs Commission

Like Yi, Liu did his time in the US, completing a masters of public administration in 1993 and 1994, focusing on international finance and trade, and spent the year before that as visiting scholar at Seton Hall University in New Jersey. But he can also claim ties to the establishment, having spent the majority of his government career in economic and financial affairs, most recently as vice-minister at the National Reform and Development Commission, the country’s top economic policy body.

China has four vice-premiers, each with their own policy portfolio. As was widely expected before his appointment, finance falls under Liu. He led an inspection tour at the financial regulators shortly after his appointment in late March, telling officials to prioritize risk prevention.

Liu is also expected to take over the Financial Stability and Development Commission (FSDC), a coordinating body between the regulators, set up on Xi’s order last July, even though there has been no official announcement about his appointment.

The post has been held by Ma Kai, the vice-premier previously in charge of finance, who Liu replaced this year.

Liu has another important role, as head of the Central Committee for Financial and Economic Affairs, which was upgraded from its status as a central leading group to a committee at the March meeting in Beijing. This is the venue where the policy tone will be set, according to Neoh.

|

Anthony Neoh, |

“Ultimately,” he says, “the central committee, directly under the leadership of president Xi, has the authority over financial stability coordination, working with vice-premier in charge of financial affairs.”

But finance may not be the most pressing issue on Liu’s agenda.

In May, Liu returned from Washington, where he had led a delegation – which included Yi – in trade talks with US officials. That week’s discussion ended with China vowing to import more US products, temporarily averting the threat of a trade war.

International events like these could shift more responsibilities onto the other two characters in this trinity, says Ha.

“Liu He has already taken on a lot of work,” he says. “The trade conflict with the US alone can take up a lot of his time, as we can see. The FSDC will eventually be under his leadership, but a lot of the day-to-day work will be down to officials like Guo and Yi.”

That does not mean Liu will play a smaller role in shaping China’s financial markets. But his impact will probably only be felt in the long run, argues CLSA’s Lee.

“FSDC’s job is to figure out what China should do as the global financial system evolves,” he says. “There are innovations which cut across the remits of different regulators and could pile up risk in the system. What should China do with, for example, P2P lending platforms? How will the credit system evolve with the rise of internet financing companies in 20 years? FSDC is there to find the answers.”

Catching up

But before we get to the future of finance, China has some catching up to do. Almost two decades after joining the World Trade Organization, the central government has finally decided to open up the country’s financial sector to foreign majority ownership.

The ministry of finance announced last November – as Donald Trump jetted away from China after his first visit as US president – that China will lift the cap for foreign ownership to 51%, allowing a foreign shareholder to have a majority stake in financial institutions, including banks, insurance companies, securities houses and asset managers.

Previously, ownership rules varied according to the category of financial institution, but foreign ownership was typically restricted to 20% or 25%, for individual and aggregate shareholders respectively.

The ownership limits will be abolished after three years.

While the liberalization agenda is technically independent of the regulatory tightening, the two projects will turn out to be mutually complementary, says Scott at Winston and Strawn, who sees the upside from foreign participation in his area of practice.

“Foreign insurers tend to be more conservative, mature, and are better equipped to address solvency, corporate governance and compliance issues,” he says. “Also, this is still a very young market. There is a lack of products and a lack of sophistication in the existing range of products. People are still learning and exploring what insurance can do. The international players will bring sophistication to this market, even if their market share is currently quite small.”

CLSA’s Lee says that as Chinese finance intertwines with the global economy, the central bank – and, by extension, its dual chiefs – will have a more active role to play.

“Opening up its financial sector and supporting renminbi internationalization means that China’s economy will become more tied to the global macroeconomic environment and conditions,” Lee says. “A delicate balancing act is necessary to fend against potential risk arising from onshore and offshore tapering.”

History is being written right now by Liu, Guo and Yi. It makes for a story that is as good and as dramatic as any in ‘The romance of the three kingdoms’.