When Pakistan’s new finance minister Asad Umar sat down with Asiamoney in early February, six months into his term, to explain how his government was repairing this broken nation, he seemed ebullient and upbeat that Pakistan was – at last – being transformed.

Yes, he admits, he has inherited an economic emergency, with foreign exchange reserves slumping below $7 billion late last year as pressing external debt rose beyond $100 billion.

It was “a full-blown crisis,” he says.

But the country has stabilized on his watch, he adds. As for a deal with the IMF, Umar seems to have a bet each way on whether or not Pakistan, an IMF addict that has spent 22 of the last 30 years as a fund patient, would need yet another intervention.

|

That said, support from the fund would be welcomed “because of the credibility that it brings.”Pakistan, Umar claims, is managing well enough, and Islamabad really does not need IMF help because the $8 billion recently pledged in fraternal support from friendly Gulf nations and China should be sufficient.

He advocates zero tolerance for the corruption that overwhelms the country and that places it 117th out of 180 countries ranked by Transparency International. He says there must be a commitment to ethical transparency and performance-based results in government.

Umar, a former businessman, has set himself some ambitious targets. He wants Pakistan’s economy, which has chugged along with growth of around 5%, to surge so that it no longer lags its emerging market neighbours, India, Bhutan, Nepal and Bangladesh.

And he is proud that Pakistan’s creaking tax system, which consistently fails to gather as much revenue as it should and which last year raised about 15% less than expected, is being streamlined with cutting-edge technology that could identify dues from around the world.

Just 1% of Pakistanis pay income tax, according to Pakistan’s Federal Board of Revenue.

You could see Pakistan was in a full-blown crisis. In this particular case, it wasn’t worse than we expected, it was as bad as we had been warning - Asad Umar

Pakistan’s markets and currency show signs of optimism, he says, and confident foreign investors are back, signing big deals. Exxon Mobil, Umar’s former employer, has announced its return after a 27-year absence, with plans to drill again for oil and to build an LNG gas terminal. Drinks firm Pepsi has also flagged a $1 billion investment in Pakistan, while US agribusiness group Cargill plans to invest $200 million.

With improved security, international airlines are re-establishing routes to the country: by June, British Airways is expected to commence direct flights from London that were stopped 11 years ago after the 2008 bombing of the Islamabad Marriott Hotel. That in turn could revive the tourism sector, which has been crippled by repeated terror attacks.

Many in the country’s vast and influential diaspora are returning on those flights to scope out prospects for investing the fortunes they made abroad so they can help rebuild their homeland.

It all seemed pretty good news, for a country in dire need of a break.

Optimism

A few days later, Umar’s buoyancy was underlined when he and the prime minister, Imran Khan, lavishly hosted Saudi Arabia’s effective ruler, Crown Prince Mohammad bin Salman, on a visit to Islamabad. The Saudi prince promised $20 billion in new investment, on top of the $6 billion in financial assistance that Khan and Umar had secured from the Saudis soon after taking office last year, and which averted a balance of payments crisis.

The Crown Prince hailed Pakistan as “a very, very important country of the coming future”.

Umar’s business-like optimism contrasts starkly with the atmosphere in his ramshackle ministry in Islamabad, where armies of civil servants spend their days playing with their phones, chatting, watching TV or drinking tea, many seeming to be doing anything other than actual work.

But listening to their boss, six months after he became Pakistan’s paramount economic decision-maker, one could be mistaken for thinking Umar was shaping an economy that looked positively Scandinavian – a far cry from the basket case reality.

|

| Asad Umar |

How quickly things turn in this capricious country. As February drew to a close, Umar’s shiny new Pakistan was looking distinctly like the tarnished old version, doomed to a forever fight with its powerful neighbour India, and fated to yet another stint in the IMF emergency ward, its 13th in 30 years, a dubious record.

On February 13, Umar assured Asiamoney that Pakistan thrives when there is peace on its borders. The following day, a suicide bomber from a Pakistan-based militant group killed 46 policemen in disputed Indian-controlled Kashmir. India responded swiftly. The next time Umar was seen, he was on national TV, grim-faced and sitting alongside the prime minister and senior military brass in an Islamabad war room, after Delhi and Islamabad had exchanged air raids in the most serious escalation of their Kashmir conflict in decades.

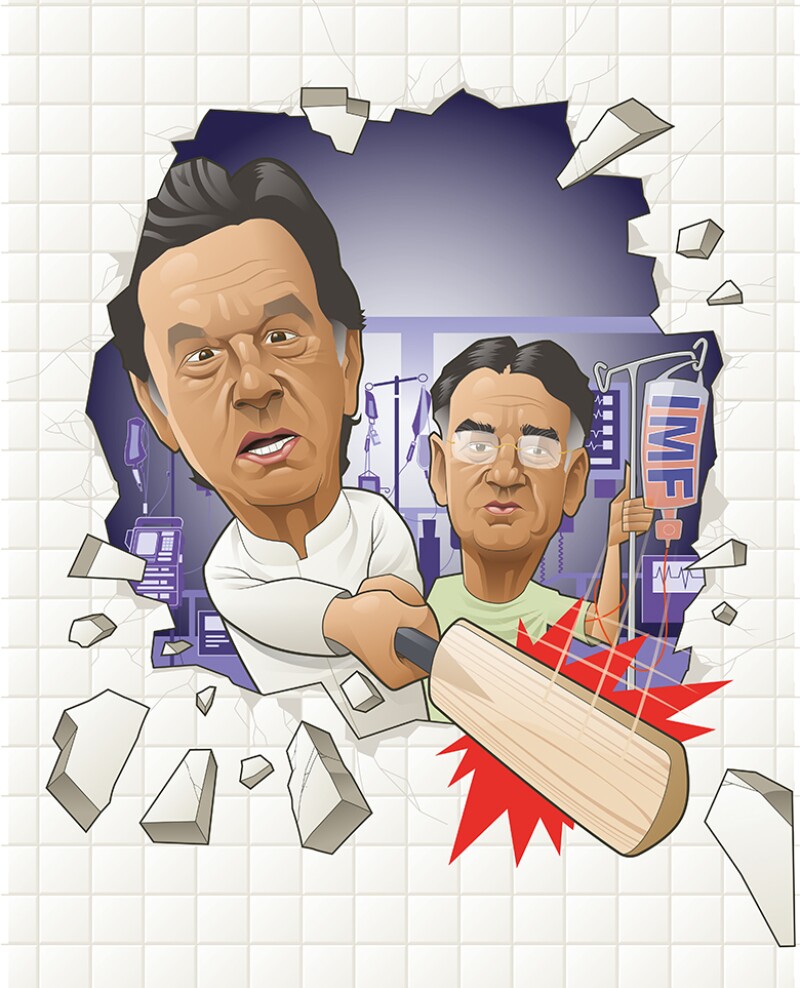

With those attacks, the honeymoon that Khan and Umar, Pakistan’s new dynamic duo, had enjoyed was over. Now Pakistan stood again on the brink of war with India, the first time in history that two nuclear powers had launched air strikes on each other.

Some economists now fear that spate of foreign investment deals could falter.

At the height of tensions, Umar told his 5.65 million Twitter followers – who are accustomed to his relentlessly upbeat economic messages and inspirational memes – that “India WILL get a response…INDIA CANNOT WIN.”

But, as bilateral bellicosities tempered into their usual mutual finger-pointing, Umar made a plea for peace on February 28, tweeting “we are at the crossroad of history. Leadership of India & Pak need to decide if we want to lead our nations towards peace & prosperity or conflict. Pak remains committed to peace while resolute in defence of our sovereignty, for which we have demonstrated both our capacity & will.”

In early March, Pakistan handed back an Indian airman it had shot down, and promised a crackdown on militants.

Reforms

A few days before Umar met Asiamoney in mid February, Khan and Umar had flown to Dubai, ostensibly to officiate at Dubai’s annual World Government Summit. As Pakistan’s new salesman-in-chief, Khan gave a well-received speech, assuring the audience that Pakistan was changing.

“We have our reforms agenda,” Khan told the conference. “Reforms are painful, it’s like a surgery. The worst thing that can happen for society is that you keep postponing reforms because of the fear that you would have opposition, the vested interests.”

Khan went on to outline the main economic goals.

“We’re trying to improve all our economic policies, trying to cut down our fiscal deficit, improve exports, cut down our imports,” he said. “We’ve started working on ease of doing business… we’re changing our tax laws, which were very cumbersome.

“You must allow businesses to make money; investors must make profits. And the reason is simple… if they can make money, more people come and invest. So, this is what we’ve done. We feel that this is the time that Pakistan will take off.”

While Khan was firing up the audience, Umar was engaged in the real work of the Dubai visit, arm-wrestling with the IMF team who had accompanied the fund’s managing director, Christine Lagarde.

Reforms are painful, it’s like a surgery - Imran Khan

A deal was struck, which is not what Umar was flagging a week or so earlier when he told a Karachi business lobby that after the Saudi, UAE and Chinese support deals, Pakistan would not be entering another IMF programme “for now”.

Why the sudden change of mind, Asiamoney asks?

Umar chortles.

“What has changed are the headlines in the newspapers,” he says. “What I said never changes. There was never a point where we stopped engaging [with the IMF]. We could’ve gotten by without the IMF, but the desirable thing when we started discussions was a good IMF programme,” he adds.

“There is an increasing likelihood that there will be an agreement and that we will be able to have a programme… It will be, almost certainly, an extended fund facility, which is a three-year programme.

“We had said from day one that we are negotiating a programme with the IMF,” he says. “We want to be in that programme, but at the same time we’re also trying to line up alternate financing so that we’re not dependent on the IMF alone.

“We don’t need the IMF to survive, but I would still want to be in an IMF programme because of the credibility that it brings and the signals to the market, the separate framework that provides for us to follow through with the stabilization steps that we need to take.”

A $12 billion injection has been mooted, this less than three years after Pakistan under Nawaz Sharif had paid back a previous $6 billion intervention from the fund.

But the new deal remains a way off, Umar says. Pakistan and the fund have shared their financial and budgetary outlooks, he says, “but they don’t match. If they matched, we would have signed by now, but are we closer than when dialogue first started? Absolutely. Substantially closer.”

Things had been grim at the end of 2018, says Saad Hashemy, chief economist of Karachi-based brokerage Topline Securities, “but since the injection of the Saudi money, we have stabilised. That has given us some breathing space.”

As the new Imran government adjusted to office, Hashemy says there has been “some nice words but not much going on”, but the recent funding boosts from the Gulf had made him more optimistic. As for Umar’s pledges to reform the economy, Hashemy says “he’s a bright guy, the right man for the job.”

Like many Pakistani economists, Hashemy sees IMF intervention as inevitable.

“The IMF intervention is going to happen,” he says. “Pakistan needs $20 billion to $25 billion every year based on our debt repayments and current account deficit. So how are they going to fund next year? The funding gap is still there. You need the IMF discipline.”

In return for IMF support, Hashemy says the fund will demand a hike in interest rates and a devalued rupee. He sees 150 rupees to the dollar in the medium term – it was 139 in mid March – and GDP growth for 2019 at a sub-par 3%.

Umar admits there will be a domestic political cost, which could be tricky for what amounts to Pakistan’s electoral experiment with this Khan-led government.

“It’s not whether you sign with the IMF or not,” he says. “Some of the decisions that have to be taken for the stabilization will be painful.”

|

| At a summit in Dubai in February, Imran Khan fired up the audience, while his finance minister arm-wrestled the IMF |

Emergency

It’s a universal rite of political passage that when a new government reviews the national accounts after taking power, one of its first assertions is to tell voters that the economy is in dire straits. More often than not it’s an exaggeration, but not in Pakistan.

“When we walked in,” recalls Umar, “it was an emergency: the rate at which the reserves were depleting, the current account deficit that was running, no financing lined up at that point. Emergency would be a minor word for that.

“The economy was left in a shape which simply wasn’t sustainable – $2 billion a month current account deficit, at a pace of almost 8% of GDP, that is simply not sustainable,” he says. “That simply doesn’t allow for business as usual to continue.

“You could see Pakistan was in a full-blown crisis. In this particular case, it wasn’t worse than we expected, it was as bad as we had been warning. I have been warning about this for three years, you could see the path down where we were heading. It’s a heck of a challenge that was handed to us.”

Ratings agency Moody’s, for one, is still to be convinced. In February, it assigned a negative outlook to Pakistani banks, citing sharply slower economic growth in 2019, rising inflation and the banks’ increased exposure to government paper.

In the same month, Standard & Poor’s cut Pakistan’s long-term sovereign rating from B to B-minus, blaming “diminished growth prospects as well as elevated external and fiscal stresses.”

Saviour

For Umar, now 57, the creaking finance ministry is a far cry from his former life. He had built a reputation as one of Pakistan’s corporate titans, joining the privately owned fertilizer company Engro Corporation in 1985 and, over 27 years – the last eight as chief executive – turning it into one of Pakistan’s biggest conglomerates.

I was enjoying my life and then Imran Khan came after me, again, again and again - Asad Umar

Today, as finance minister, he spends long hours in the office, many alongside the leader he calls Skip. That’s Umar’s nod to the storied sporting legacy of Khan, who leveraged an international cricketing career into years of grassroots activism before becoming, as many Pakistanis see him, the saviour of a broken land.

Last July, Khan’s Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (Pakistan Movement for Justice) party broke the country’s feudal political cycle and was elected with a pledge to create 10 million jobs and build an Islamic welfare state.

Did Umar want to be a politician? His answer is emphatic.

“Nope. Not at all. Did I expect Imran Khan would become the prime minister of Pakistan? I was absolutely sure he was going to make it.”

|

| Imran Khan |

He says Khan approached him to join his movement while he was at Engro.

“I was enjoying my life and then Imran Khan came after me, again, again and again.”

Umar says his retirement plan was “to run a small not-for-profit educational institution and watch a lot of cricket around the world. Politics had nothing to do with it. [Imran] pulled me aside and said: ‘Asad, the country needs you’. I finally said: ‘Yes, let’s do this’.”

The two form a formidable duo. The last time Pakistan had a double act like this was during General Pervez Musharraf’s dictatorship when he appointed former Citibanker Shaukat Aziz as his reformist finance minister in 1999. Umar was the only person in Khan’s circle whose portfolio was flagged long before Khan won power.

“What happened is surely a miracle.” Umar says of the PTI win. “The vast majority of Pakistanis said there was a snowflake’s chance in hell that Imran Khan would be able to break this stranglehold.”

Diaspora

There is much to do, a possible war with India notwithstanding.

“Things have improved, but we are clearly not in a situation where we’re looking at healthy growth and that all our problems have gone away,” says Umar. “There is a lot of work that still needs to be done.”

The new government is tapping the diaspora to invest back home. The estimated eight million expatriate Pakistanis worldwide, including more than one million in the UK alone, already send annual remittances of about $20 billion, according to the central State Bank of Pakistan.

But Umar is targeting wealthy overseas Pakistanis, urging them to invest in Pakistan.

In January, the new government launched so-called diaspora bonds. The scripless bonds have two maturities; a three-year bond with a coupon of 6.25% and a five-year bond with a coupon of 6.75%. The minimum investment is $5,000, with no upper limit.

“We wanted contact with the overseas Pakistani living abroad who is, frankly, starved for yield in those markets,” Umar says.

The bonds are designed to trade off Khan’s international lustre.

“Imran Khan resonates with overseas Pakistanis, he’s amazing, his 20 years of social welfare work has been largely sustained by overseas Pakistanis,” Umar says. “There’s a special bond there, and in our efforts to rebuild Pakistan we wanted the overseas Pakistanis to play a significant role.”

He’s also going after corruption, especially funds salted away offshore, and expects the international community to cooperate with him in getting the money back.

“How much is out there? Nobody knows,” he says. “This is ill-gotten wealth, parked abroad and not disclosed to the tax authorities because of the weak reporting systems we have here. But it runs into billions of dollars for sure, probably tens of billions.

“Am I relying on any of that for the financing needs of Pakistan? No, because there is a tremendous uncertainty in terms of the time it will take for the money to fly back into the country.”

Imran Khan resonates with overseas Pakistanis... There’s a special bond there, and in our efforts to rebuild Pakistan we wanted the overseas Pakistanis to play a significant role - Asad Umar

Umar says he wants to plant two thoughts in the minds of Pakistanis: “One; that it is easier to make money in Pakistan right now and the government is there to make it easier for them to start a business, to make money and grow wealthy. At the same time, we want them to feel that there is an increasingly high cost of trying to earn illegitimate money, or trying to hide money. There is a zero tolerance on corruption now. The two go together. People are now saying: ‘These guys are serious and they are pursuing our money’.”

As for tax collection, he wants to modernize the reporting procedure, using artificial intelligence and data analytics to determine who isn’t paying.

Tax amnesties – Pakistan has had four in six years – have failed, he says.

“If another amnesty is to be done, it will have to be, to quote Saddam Hussein, the mother of all amnesties. Or the last amnesty that is ever going to be done,” he adds.

“Clearly what has happened in Pakistan is the creation of a moral hazard, when people believe there is an amnesty coming down the road – and that’s a hindrance to getting people into the tax net. Let’s just say that’s not the first solution we’re thinking of.”

Privatization

As finance minister, Umar also chairs the government’s moribund privatization commission. Some state companies have been on the list for 25 years.

“It’s a ridiculous situation,” he says. “The moment they are put on the list, they’re no longer managed as going concerns. As a result, all that has been done is eroding value.”

On his watch, 11 enterprises have been slated for privatization over the next three years, prominent among them small banks SME Bank and First Women Bank.

The long-mooted privatizations of National Bank of Pakistan, the second-biggest bank after privately owned Habib Bank, and of airline PIA have been shelved.

At NBP, Umar has approved the appointment of veteran Citibanker, Arif Usmani, as chief executive, which he says is an example of skilled expatriate Pakistanis returning home to contribute.

Umar says privatizations will be open to foreign investors, and that he is finalizing financial advisers. The returns, he says, will be “north of $1 billion”.

One question for those foreign investors is, just how secure is the Khan government? Generals have held power for almost half of Pakistan’s 72 years of independence.

Since coming to office, the Khan government has been under relentless assault from the wounded Bhutto and Sharif clans who have grown accustomed to exchanging power. Analysts say Khan has the support of the military, so long as his reformist zeal does not extend to dismantling the generals’ $25 billion business empire.

Pakistan’s growth model is broken, Umar says.

“It has been a consumption-led, imported capital finance model,” he says. “We should shift our transition, which we are doing right now, to an investment-driven, export-oriented growth model,” absent of the IMF.

“When that is in place, I will sleep easy at night.”