By Jonathan Breen

"Banking is not like it used to be,” says the chief executive of a leading bank in Cambodia. “It was previously like selling beer – you kept selling until the customer got drunk and they wanted more.”

Things have become a bit more sophisticated than that.

Cambodia’s banking sector is saturated, with 43 commercial banks, numerous specialized banks, micro-finance institutions and hundreds of smaller lenders. But most of the lenders at the top of the league tables are exploring online banking and mobile apps, particularly following a drive by the National Bank of Cambodia.

At the same time, there are several financial technology companies operating in niches where banks are falling behind, in areas that don’t require bank accounts.

Of our 44 digital staff, none have banking experience. They have their own floor that looks like a Google office - Askhat Azhikhanov, ABA Bank

Among the largest fintechs operating in Cambodia are Thailand’s TrueMoney and home-grown Wing, both transaction payments and money-transfer services providers. Local fintech Pi Pay, the leading cashless payments provider, also offers Groupon-style discounts to attract customers. The fintech bulldozers that are Alipay and WeChat are only seen when catering to Chinese tourists.

ABA Bank caught on to the digital revolution remarkably early thanks to a small team of bankers from Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, their need for capital, and experience operating in developing markets.

“One competitive advantage we had was that we came from an emerging country,” chief executive Askhat Azhikhanov tells Asiamoney. “We knew how to do banking and business in a developing country. Cambodia in 2009 was like the Kazakh banking system in the 1990s. It was like a time machine.”

Originally founded in 1996, Advanced Bank of Asia seems an ironic name for a one-branch institution that by 2009 was still at the bottom of the pile in a frontier market. Better known today as ABA, it was the bank’s move into digitalization, driven by this group of central Asian financiers, that turned it into one of Cambodia’s largest leading banks. Along the way, the bank caught the eye of National Bank of Canada, which built its stake up to 100% by 2019.

|

Askhat Azhikhanov, CEO of |

CEO Azhikhanov, one of the team that took over the bank a decade ago, tells Asiamoney that from the beginning, they knew they would have to do something different from the traditional banks in Cambodia if they wanted to break into the upper ranks.

“When you are coming as a challenger you always have to be creative to find a way, you cannot do the same thing as everyone else, you have to bring something new,” says Azhikhanov. “It was impossible for us to build 100 branches immediately, we didn’t have capital to do that. So we thought innovation and technology can help us.”

The plan was to combine a traditional bank for lending with a purely digital funding and transaction business, and have various middle offices in between.

It launched its internet services early; five years later the bank doubled down on its digital focus with smartphones.

“We saw the emergence of fintech around 2014 and 2015. I started seeing magazine articles about how fintech could mean the end for traditional banks,” says Azhikhanov, who has been chief executive at ABA since 2012.

“I thought: ‘What could fintechs do to us? They are small and agile and innovative – we need to create a fintech company within our bank.’ So we separated a digital team from the IT team because they are responsible for IT risk and have banking experience, they are not innovators,” he says.

“Of our 44 digital staff, none have banking experience. They have their own floor that looks like a Google office.”

The bank launched its ABA Mobile app in 2015, the first from a bank in Cambodia that was compatible with both Apple’s iOS and Android operating systems for smartphones.

The two extremes of thought when it comes to designing an app are either: develop every element in-house, or build the bare bones to take advantage of existing technologies by partnering with fintech service providers. ABA went for somewhere in the middle.

It built the basics of the app in-house but then, unlike many of its peers, the bank opened up its platform to work with other companies. Its digital team continues to develop the app, with plans to add services covering areas such as entertainment, shopping and transportation, in a bid to emulate Alipay and WeChat.

The bank’s self-developed features include e-cash, which enables card-less ATM withdrawals; these were used 370,000 times in 2018. Others are ABA Pay, for the use of QR codes and cashless payments; and PayWay, an e-commerce payments service. The bank is also targeting small-business owners, with new digital services for invoices.

The bank also has a variety of partnerships with local and international fintechs. It went into partnership with Pi Pay in 2017 to link its bank accounts with Pi Pay users’ mobile wallets, enabling seamless transfers between the two.

Azhikhanov is eyeing the market share of its partners, giving Wing as an example. The payments service provider has a network of more than 6,000 merchants across Cambodia, which the bank can’t match. So by partnering with the company, ABA’s customers can use Wing’s service through its mobile app.

The question that everyone is asking, certainly in Cambodia, is whether fintech is a threat or a partner. It is both - Askhat Azhikhanov, ABA Bank

Wing’s customer base comes largely from Cambodia’s unbanked population. But ABA is trying to turn the unbanked into the banked. Through its ‘Mobile First’ strategy introduced in 2017, it is pushing mobile banking over everything else. The bank’s advertising campaigns are focused solely on its mobile app.

“The more accounts we have, the better for us to compete with Wing because more unbanked people become banked people, so they don’t need this electronic wallet because they have more options with us,” Azhikhanov tells Asiamoney. “Of course with us it is more difficult, you have to submit certain documents, you have to spend some time, but once you become bankable it is better for you.”

He adds: “So, the question that everyone is asking, certainly in Cambodia, is whether fintech is a threat or a partner. It is both.”

The more services ABA develops for its mobile app and the less use it has for external partnerships, the more it will become like a closed platform, an ecosystem unto itself.

Recent in-house additions to its app include a service for international money transfers and a mobile loan feature. This year, ABA also launched a new corporate internet banking platform for clients including Cambodian telecommunications service provider Smart Axiata, global insurance company Manulife and Coca Cola. It picked up the latter only after Australia’s ANZ sold its local joint venture ANZ Royal Bank in August 2019.

ABA is also partnering with big international players, including Chinese firms UnionPay and Alipay.

“Cambodia is such a small market for WeChat and Alipay, it makes sense they would use us,” says Azhikhanov, adding: “We are like a village for them, why would they want to establish a whole team here and fight here? Because we would fight with them.”

Banks in Cambodia compete on traditional grounds, in lending and deposits, for example. But increasingly, the biggest challenge in the digital era is the fast-changing behaviour of clients. Therein lies what has become the world’s most valuable commodity: data.

‘Big data’, if understood properly, is a goldmine for financiers. ABA has put together a team to analyze the data being collected through its app and other online services, including transaction data and payment data.

“Data is fundamental and it is so valuable, you can use it in so many ways,” says Azhikhanov. “We have to analyze this data to understand what people are doing. That will help us with our transactional lending. Instead of going door-to-door, we can just send our analyzed data to our loan department.”

ABA plans to monetize data in lending within the next three to five years, Azhikhanov tells Asiamoney.

Leading position

ABA is the third-largest bank by assets in Cambodia, with $4.1 billion, behind only Acleda Bank and Canadia Bank. Deposits are $3.3 billion, while it has a $2.5 billion loan book.

ABA was able to achieve a 28% return on equity in 2018, the highest among all of Cambodia’s commercial banks; it reported a 65% rise in assets, which have trebled in three years, while doubling deposits and generating a $71.8 million net profit, up 55% year on year. For the first three quarters of 2019, it recorded a $75.2 million net profit.

Alongside its embrace of all of things digital, the bank has kept faith with bricks and mortar, adding 15 branches in 2018 to take its total to 70 – 24 in Phnom Penh and 46 across Cambodia’s provinces. The bank has also extended business hours at locations in Phnom Penh. And its 4,200-plus staff served 706,000 customers in the first three quarters of 2019, up from 426,000 in 2018 and 232,000 in 2017.

Its leading position in digital and mobile banking, and its growth across businesses won it a ‘positive’ outlook designation this year from S&P, which has given the bank a single-B credit rating.

ABA is the poster child for the digital approach going well. It is winning the race - Bora Kem, Mekong Strategic Partners

ABA has also issued a bond. The bank printed a CR128 billion ($31.4 million) three-year note, which is listed on the Cambodia Securities Exchange. Sold in August 2019, it is only the third issue in Cambodia’s young bond market. Its reception among retail and institutional investors has encouraged the bank to print another in 2020.

The notes, which pay a 7.75% coupon, were popular among retail accounts.

“There was a good retail response, better than we expected. So we are going to do another again next year,” says Azhikhanov. “It has given us funds in Khmer riel, which we need to lend, and it is a good sign to see that people are looking at alternatives to just buying land.”

Institutional funds were also excited by the deal because Cambodia offers few opportunities to place cash beyond bank deposits, says Shuzo Shikata, chief executive at Japanese-backed local outfit SBI Royal Securities.

The domestic arms of global insurance firms Manulife and Prudential each bought $300,000 of the deal, according to Shikata, whose firm was sole underwriter of the bond.

Positive impact

ABA’s staff are now almost entirely Cambodian, but of the bank’s nine-strong senior management team, five are from Kazakhstan or Uzbekistan, including the chief executive.

The original group was formed through mutual relationships, put together at first by Damir Karassayev, a former president of the Kazakhstan Stock Exchange. Azhikhanov joined the team through his connection to Madi Akmambet, ABA’s first CEO following its revamp. The pair had worked together at the National Bank of Kazakhstan, where Azhikhanov began his career.

“I started my professional life in banking supervision at the central bank,” he says. But after three years learning about the regulatory side of finance, the young Azhikhanov decided he needed experience on the commercial side of banking and moved to the internal audit department of a local bank and on to a spell at Credit Suisse Kazakhstan for a few years, leading up to the global financial crisis.

Azhikhanov and the group of 30-somethings witnessed the calamitous effect that debt-fuelled spending and risky investment banking could have on an economy during the financial crisis and decided to try to build a bank without those elements.

The team wanted to focus on lending to businesses that have a positive impact on the real economy. In Cambodia that meant lending to micro, small and medium-sized enterprises.

“We were trying to find a place to realize that vision and Cambodia with its micro business and SME-based economy and entrepreneurship was very attractive and the perfect environment for us to build a bank with such a vision,” says Azhikhanov.

Having eschewed consumer lending, ABA has stuck to its approach. As a result, its loan portfolio by loan amount is more than 90% SMEs, covering a diverse mix of industries, from manufacturing to agriculture and trade to services. By client segment, the loan book is majority micro-businesses.

International suitors began eyeing ABA as a post-crisis opportunity. After turning away a number of potential investors, National Bank of Canada fit the bill, says Azhikhanov.

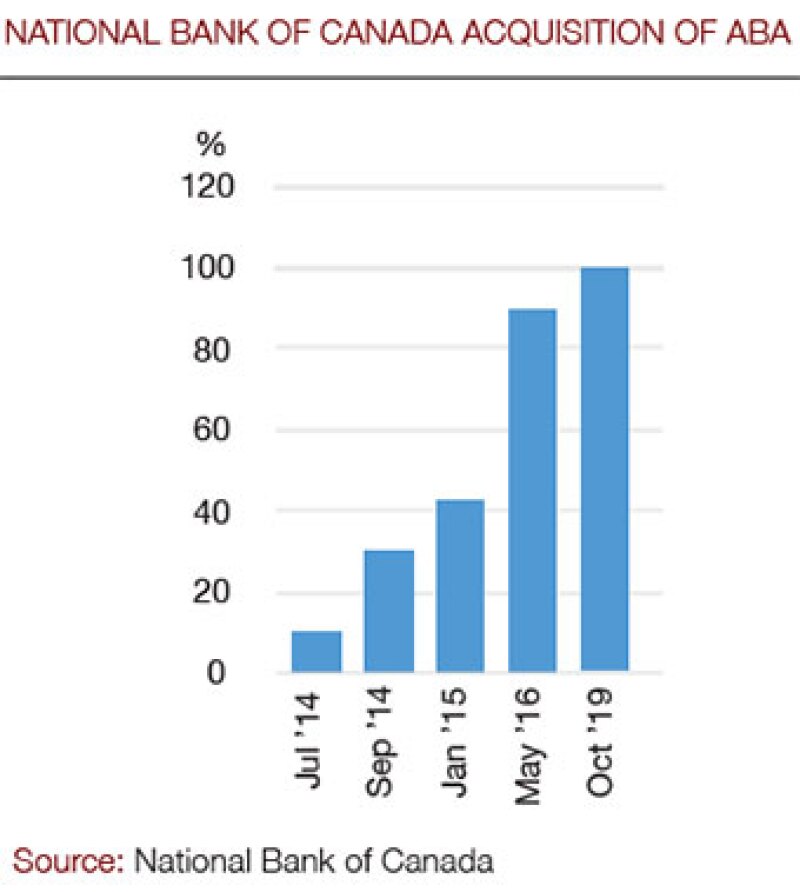

NBC made its first acquisition with a 10% stake in ABA in July 2014, which it increased to 30% in September and then to 42% in January the following year. In 2016 the Canadian bank became the controlling shareholder of ABA: having already put $45 million into the investment, it paid a further $103 million to push its stake to 90%.

“It was good for us and them, because if they had bought outright 100%, they would have replaced the management who would have wasted time understanding the bank,” says Azhikhanov.

“It is a good synergy. We know the country very well, we know the operation and we know how to do business here,” he adds. “In return they are bringing us their big name, credibility and reputation, and corporate governance, where they are strong. They are strong in compliance, risk management, and internal audits. We had that before, but you can’t compare it to Canadian standards.”

NBC completed its acquisition in October 2019 at a cost of $63 million, and now owns 99.99% of ABA – Cambodia prohibits total foreign ownership of a local company. To comply with the law, Karassayev holds one share in the bank. Karassayev now runs Paladigm Capital, an asset and wealth management firm based in Singapore.

NBC has not only given ABA successive injections of capital, but has helped the bank’s relationship with the Cambodian financial regulator through its credit rating and in capturing corporate and institutional clients.

NBC’s backing has given ABA a boost in confidence, says Azhikhanov. The support of such a large and respected international institution is an encouragement for employees throughout the bank.

'Poster child'

ABA has gone from nothing to something in barely a decade and is leading the charge into the next generation of banking and finance, with digital at its core.

“ABA is the poster child for the digital approach going well,” says Bora Kem, investment manager at Cambodian outfit Mekong Strategic Partners. “It is winning the race. You really need to have a big platform to make this business work.

“Yes an application might be very usable and you can build trust, but ultimately people will sign up for a bank because everyone around you has it.”

In the first nine months of 2019, the ABA Mobile app recorded 30 million transactions, totalling $25 billion. To put that in context, Cambodia’s gross domestic product last year was around $24.6 billion, according to World Bank data. Over 90% of ABA’s transactions by value are done by self-banking, about 50% by volume.

“Young people don’t want to go to banks, they want to solve everything on their mobile,” says Azhikhanov.

Two thirds of Cambodia’s 16 million citizens are below the age of 30, according to United Nations statistics.

“That is why we need to embrace technology and the new generation, who will be the middle class of tomorrow,” says Azhikhanov.