An NGO has filed a complaint at the US Securities and Exchange Commission, accusing the lead managers of Adani Electricity’s sustainability-linked bond, issued in July, of securities fraud for failing to disclose properly its links with coal power.

The issuer — part of the Adani Group, which sees itself as India’s largest infrastructure platform — is also accused in the complaint, but vigorously rejects the charge. “This is all malicious and completely unrelated conflation,” said Robbie Singh, chief financial officer of Adani Group.

The group has interests in coal-fired power and owns three coal mines, including the controversial Carmichael mine in Queensland (pictured above), which has been the target of environmental protests for years. It also has a green energy division and is converting parts of its activities to renewable power — including Adani Electricity, the issuer of the SLB.

Some of the group’s coal activities, but not the Carmichael mine, were disclosed to investors in the SLB. The bond was marketed using a second party opinion by Vigeo Eiris that said Adani Electricity was not involved in the controversial activities of coal or fossil fuels. After the bond had been priced, Vigeo Eiris changed this statement.

The NGO’s complaint raises a question many sustainable finance specialists do not have an answer for: how much should an issuer disclose about environmental, social and governance controversies at other companies in its group?

Disclosure criticised

The $300m bond was priced on July 15 by Adani Electricity Mumbai Ltd, primarily an electricity grid business, which has a 25,000km network serving the Mumbai area. It also owns a 500MW coal-fired power station at Dahanu, 120km north of Mumbai.

The bond was lead managed by MUFG — which was also the SLB structuring agent — Axis Bank, Barclays, Citigroup, DBS Bank, Deutsche Bank, Emirates NBD, JP Morgan, Mizuho and Standard Chartered.

The objection has been made by the Anthropocene Fixed Income Institute, a small organisation in Stockholm led by Ulf Erlandsson, a former bond investor and green bond specialist, which campaigns on climate issues in the fixed income market.

“This is not about me being against all coal,” said Erlandsson. “It’s about companies disclosing properly in the bond market.”

The AFII filed its formal complaint with the SEC on September 6 and copied it to the banks on September 24. It alleges that the bookrunners and the issuer committed “fraudulent misstatements and omissions of material fact” in violation of US securities law.

The central charge is that even though this was a sustainability-linked bond, the issuer and lead managers failed to make clear Adani’s connection with the Carmichael mine, which many investors have pledged not to invest in.

“If you’re doing an SLB with a company that has bad stuff on its balance sheet, you need to flag it,” Erlandsson said. “You should be open about it and let investors understand [the company’s] transition journey, because known unknowns are much better for investors than unknown unknowns.”

Erlandsson emphasised that this was not litigation. “We have filed a complaint with the SEC — they can choose whether or not to look into it,” he said. “We think there are clear concerns with regard to the bond issue and we want it to be evaluated.”

The action comes as the SEC is raising its expectations of how much companies disclose about the risks and opportunities they face from climate change — which include risks that coal power is phased out or boycotted by investors.

Since 2010 the SEC has explicitly required firms to publish their climate change risks, but in September it notified issuers that it had been reviewing corporate disclosures and might write to them to point out gaps or unclear disclosures.

Long struggle

The Adani Group, controlled by Gautam Adani (pictured), a businessman who enjoys a close relationship with India’s prime minister Narendra Modi, is one of India’s most important business organisations.

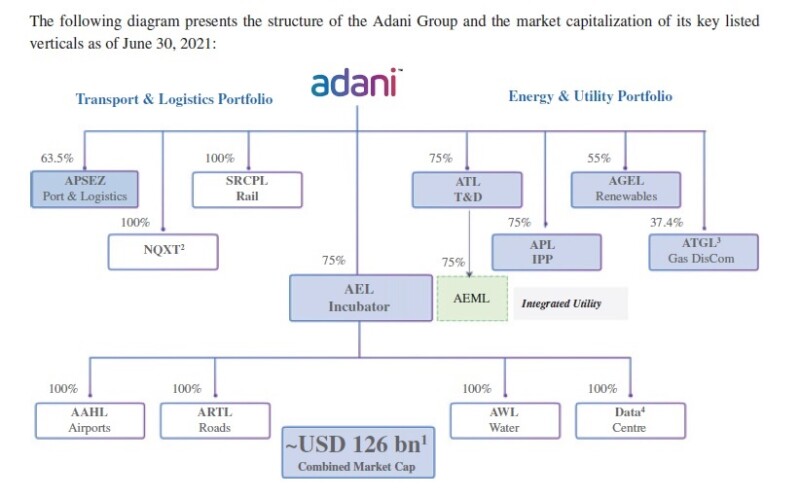

Its wide-ranging interests are held through six listed companies with a combined market capitalisation of $89bn as of July 30. Adani calls itself India’s leading player in each of renewable energy, thermal power and ports. It also owns airports, railways, roads, power distribution, gas distribution and water assets.

However, Adani is also a long-standing bugbear of environmentalists, because of its wide involvement in coal and other fossil fuels.

Since 2010 it has been trying to build the Carmichael coal mine in Queensland, to supply high quality coal to India. As originally planned, to produce 60m tonnes a year, it would have been one of the largest in the world, shipping 2.3bn tonnes over a 60 year lifetime.

Those concerned about climate change have some patience with countries that rely on coal for power and need to transition to renewable energy. But they have little time for companies and countries that are expanding coal production or building new coal-fired power plants, at a time when scientists say all fossil fuels should be being phased out, to give any chance of avoiding catastrophic climate change.

There have therefore been many protests against the Carmichael mine in Australia and around the world, which have spread from targeting Adani itself to institutions financing it. In response to the pressure, many banks have either pulled out of financing the mine or declared they will not finance it, including Barclays, Citigroup, Deutsche Bank, JP Morgan and Standard Chartered.

Mine opens as port struggles to refinance

Despite the Carmichael mine’s unpopularity, years of legal challenges and the loss of direct financing from large Western banks, it has now opened.

On June 24, Gautam Adani’s birthday, he tweeted: “Proud of my tenacious team who mined Carmichael’s ‘first coal’ in the face of heavy odds. There couldn’t be a better birthday gift than being able to strengthen our nation’s energy security and provide affordable power to India’s millions. Thank you, Queensland and Australia.”

However, the protests have not left Adani unscathed. Almost as controversial as the mine, and also excluded by many financial institutions, is the Abbot Point coal port 300km away, which Adani signed a lease on in 2011 and is expanding, to ship more coal from the region including Carmichael.

In March 2020, Fitch downgraded the port company Adani Abbot Point Terminal from BBB- to BB+ after it failed to complete a bond issue to refinance $410m of debt maturing between then and September 2021.

AAPT used a loan of A$270m from another Adani entity to repay debts due in 2020. In October, the business was renamed North Queensland Export Terminal (NQXT).

This year, the Adani Group supplied funds in May for NQXT to repay $140m of debt on September 22.

The money may be a personal contribution by the Adani family. But the injections have led NGOs to be suspicious that Adani might be transferring money from other Adani companies to the Carmichael project.

Next year, NQXT will need to refinance a $500m bond due in December 2022.

S&P Global affirmed NQXT’s rating at BB- (negative outlook) in May, saying that “Although near term liquidity risks have dissipated, we believe refinancing risks and borrowing costs… remain high. This is evidenced by the project’s inability to refinance multiple maturities through 2020 and 2021 and instead having to turn to its ultimate parent to provide shareholder loans and A$100m in equity funding.”

The next refinancing, if it is accomplished in the market rather than from an intercompany transfer, may need to be done via minor or regional banks, since many large ones will no longer work for Abbot Point.

Still friends

However, that does not mean these banks have ended their support for the wider Adani Group. Other Adani companies have had fruitful access to the capital markets, including with green and sustainability-themed financings.

This year, some investors and banks have also begun to withdraw from the bonds of Adani Ports and Special Economic Zone (Apsez). It owned Bowen Rail Co, which operates the rail link to Carmichael. There has also been scrutiny of its relationship with the Myanmar military, which has committed human rights abuses. The latter caused S&P Dow Jones to remove Apsez from its Dow Jones Sustainability Indices in April.

Andreas Bjørbak Alnæs, senior sustainability analyst at Storebrand Asset Management in Lysaker, Norway, said: “We have excluded Adani now — we don’t own any shares or bonds, because… they have a certain percentage of coal in electricity generation. Building the Carmichael mine is definitely an issue. We are not going to spend time engaging with them — we’ve tried to no avail.”

Storebrand had also excluded Apsez because of the Myanmar human rights issue.

The firm’s published exclusion list contains Apsez, Adani Enterprises, Adani Power and Adani Transmission.

In March, Apsez sold Bowen Rail to Adani Enterprises. In late July, Apsez issued a $750m bond with 11 major banks as bookrunners, despite recent news that Indian regulators were examining the Adani Group’s six listed companies to ensure they comply with securities laws.

Adani Wilmar, a foods joint venture, is also preparing for a Rp45bn ($600m) IPO.

Adani Green Energy, formed in 2015 and floated in 2017, is developing very large solar power plants. It issued a green bond in 2019 and another in early September, raising $750m.

With these deals, led by groups of major international banks, Adani has tapped into the worldwide wave of enthusiasm to invest in sustainable debt, by highlighting its green and climate-friendly activities.

So it was with Adani Electricity Mumbai Ltd’s SLB. The company aims to raise the percentage of electricity it buys that is from renewable sources from 3% in 2019 to 60% by June 30, 2027. If it fails, the bond coupon will step up by 15bp from January 2028.

The bond’s second target is for AEML to cut the greenhouse gas emissions intensity of its Ebitda 60% by June 30, 2029, from a 2019 baseline. This year it has achieved a 31.6% cut.

Failure on this target would lead to another 15bp step-up, from January 2030. The bond matures in July 2031.

These are material and quite rapid changes in a green direction.

The AEML bond was a great success: it attracted $2.7bn of orders from 190 investors, and was allocated 49% to Asia, 27% to EMEA and 24% to the US.

Targeted campaigns

Since it began operations in July 2020, the Anthropocene Fixed Income Institute has been campaigning for investors and investment banks in the fixed income markets to take more climate-friendly stances. This includes criticising financings for organisations it argues are damaging the climate particularly badly, as well as supporting finance for green causes.

The AFII has previously argued investors should not buy the bonds of the Queensland and Australian governments, because their money could be on-lent to subsidise coal and other fossil fuel activities.

In January, it protested against six banks for lead managing a bond for State Bank of India, which at the time appeared to be the only bank still willing to finance the Carmichael mine, and which was then expected to provide a $650m loan to Adani for it.

In March the AFII argued six banks that led a bond for Korea National Oil Corp, which owns Harvest Energy, an oil producer in Canada’s tar sands, were being inconsistent with their own climate policies and might be taking legal risks. The AFII employed legal counsel to advise it on US securities law before writing to the banks.

But the formal complaint to the SEC about the Adani Electricity bond, also written with the advice of US counsel, marks an escalation in the Institute’s tactics.

Legal basis

The AFII welcomes Adani’s moves to transition to renewable energy. It does not argue that an Adani company issuing a sustainability-linked bond must be considered greenwashing.

“I want to be clear — we are not criticising Adani with regard to the particulars of the SLB conditionality,” said Erlandsson. “What we are critical of is that there is a lack of disclosure.”

The complaint concerns the communication to investors about the SLB before it was issued.

It refers to two well known passages of US securities regulations.

Rule 10b-5 of the Exchange Act makes it “unlawful for any person, directly or indirectly… to omit to state a material fact necessary in order to make the statements made, in the light of the circumstances under which they were made, not misleading.”

Facts are material, the AFII’s counsel advised, where “there is a substantial likelihood that a reasonable investor would attach importance in determining whether to buy or sell the securities registered.”

Counsel added that Section 17(a)(2) holds that, to be found liable for claims of fraud thereunder, a person must have acted “to obtain money or property”.

The Institute argues that Adani Electricity and the bookrunners broke these rules in the way they described the bond issue before the sale, specifically in the offering circular and the second opinion by Vigeo Eiris.

Missing points

In the first place, the AFII argues, the issuer and banks failed to disclose six material facts. First, that Adani Electricity was affiliated with Bravus Mining and Resources (formerly Adani Mining), which owns Carmichael. Bravus is wholly owned by Adani Enterprises, one of the listed companies in the Adani Group.

Adani Electricity is 74.9% owned by Adani Transmission, another listed company.

As of March 31, Gautam and Rajesh Adani owned 56.5% of Adani Enterprises and the same percentage of Adani Transmission.

Second, Bravus, Adani Enterprises and Adani Transmission, as well as other Adani affiliates, are listed on the Global Coal Exit List, a database of companies involved in the thermal coal value chain, which the AFII said “serves as a resource for investors and financial institutions seeking to reduce their exposure to coal”.

Third, that Bravus owns Carmichael, expected to produce 10m tonnes a year of thermal coal.

Fourth, “Demand for coal generated by Adani’s coal-fired power plants is the primary motivation for the development of the Carmichael project and, once completed, Adani will be the Carmichael project’s single largest customer.” The complaint quotes Singh as saying Carmichael would be “a support business for Adani Power”.

Fifth, that Carmichael is “arguably the most controversial greenfield fossil fuel project globally”, alleged to be harmful to ancestral Aboriginal lands, land and marine wildlife as well as the climate.

Sixth, that about 50 leading financial institutions had publicly stated they would not finance the Carmichael project.

A list of financial institutions that have excluded Adani entities because of Carmichael is maintained by Market Forces, an Australian NGO. The Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis keeps a list of over 150 institutions with coal exclusions.

Not mentioned

The offering circular does include sections describing Adani Electricity’s coal-fired power station and how it faces risks such as not being able to secure enough coal.

It refers to AEML importing higher quality coal to supplement domestic supply but says: “Most of our imported coal is sourced from Indonesia.”

There is no mention of the possibility of importing Australian coal.

The OC also warns that as renewable generation increases, coal plants might become less efficient. It acknowledges that “If we are unable to adapt to technological changes, our business could suffer… The dynamic scenario of the power generation sector, which is moving towards renewable energy generation, faces many challenges”.

However, the OC does not mention Carmichael, Bravus, Abbot Point or Australia.

A diagram in the OC showing the structure of the Adani Group does not show Bravus or Carmichael (pictured). It mentions Queensland in a footnote, to explain that “NQXT” in the diagram refers to North Queensland Export Terminal.

‘No controversies’

The AFII also argues that Adani and the banks broke the law by circulating the Vigeo Eiris second party opinion (SPO), “despite the SPO containing a manifest misstatement of material fact. Specifically, the SPO stated that Adani is not involved in coal activities”.

The SPO did not refer at all to any of the Adani Group’s coal activities. A tickbox list of 17 possible controversial activities, including coal, had none ticked, and was accompanied by a statement that AEML was not involved in any of them.

On July 21, Vigeo issued a revised SPO, stating that AEML was involved in two of the 17 controversial activities: coal and fossil fuels.

But this was six days after the bond had been priced and two before it settled. Investors had already relied on the SPO, the AFII argues, and “The closing of the offering was not postponed to ensure that investors had adequate time to review the revised SPO.”

Vigeo’s revised SPO said the changes on controversial activities did not alter its opinion as to the bond’s “sustainability credentials”.

Its brief explanation of the coal controversy referred only to the Dahanu plant owned by AEML and said this produced less than 5% of AEML’s turnover. It did not refer to any other coal activities of the Adani Group.

Finally, the AFII’s complaint argues that “omitting and misstating the above material facts suggests an intentional effort by Adani and the [banks] to downplay the significance of Adani’s coal-related activities.”

It adds: “the motivation… was to secure investment from investors otherwise prevented from financing coal-related activities”.

MUFG responds

Contacted by GlobalCapital with questions about the complaint, Barclays, Citigroup, Deutsche Bank, JP Morgan, Mizuho and Standard Chartered declined to comment. Axis Bank, DBS and Emirates NBD did not reply.

Neither did Linklaters, which advised AEML on US federal and English law in relation to its global MTN programme, nor Latham & Watkins, which advised the programme’s sole arranger and dealer, Standard Chartered.

MUFG, which had been the SLB structuring adviser, said it would not comment on any ongoing legal matter pertaining to an individual company. “For the avoidance of doubt,” the bank said, “we categorically object to suggestions and/or allegations that we are involved in the said project in Australia. We would stress that MUFG has a robust framework that ensures that the utmost due diligence is carried out and all local and global regulatory requirements are observed when evaluating every business transaction and client relationship.

“MUFG takes its mission of contributing to the sustainable growth of clients and society seriously, and is therefore committed to operating in a manner that is both socially responsible and in accordance with the long term developmental requirements of the markets that it operates in. We have revised our Environmental & Social Policy framework to ensure that financing of any coal-fired power plants will be prohibited. This took effect from June 1, 2021.”

GlobalCapital asked MUFG to clarify how financing AEML, which owns a coal-fired power plant, could have been consistent with this policy, but it did not reply.

However, its public policy indicates that the prohibition is only on financing new coal-fired stations, or expansions of existing ones. Exceptions can be made for those using carbon capture and storage or “mixed combustion”.

‘Administrative error’

A spokesperson for Moody’s, which owns Vigeo Eiris, responded by email to questions from GlobalCapital. He said: “Our Second Party Opinion on Adani Electricity Mumbai Ltd’s Sustainability-Linked Bond was republished on 21 July 2021 to include a reference to involvement in the coal and fossil fuels industry as controversial activities of the issuer, which had been omitted from the original document due to an administrative error. As that information had been considered in the initial SPO, our analysis of the sustainability credentials of the bond was not impacted.”

As the Carmichael mine belongs to Adani Enterprises, and Vigeo considered that there was no direct link between AEML and Adani Enterprises, Carmichael was not part of the scope of the SPO.

Adani’s arguments

Jugeshinder ‘Robbie’ Singh, Adani Group’s CFO, spoke to GlobalCapital and answered questions in detail. He said he was confident the SEC would conclude that the complaint had no merit.

As of the end of September, the SEC had not yet contacted Adani about it. Nor has it contacted the AFII.

Asked why Adani had not disclosed Carmichael in the documents for the bond, Singh gave several arguments.

“There is no such thing as Adani Group,” he said. “There is no holding company. It’s a very deliberate attempt to link unrelated businesses. We have a portfolio where we invest, with six large companies. It’s all public and disclosed in the offering circular on pages 203 to 204.”

In one of the six listed companies, Adani Total Gas, a joint venture with TotalEnergies, the Adani family has a minority stake. In the other five, it has majority stakes, ranging from 55% to 75%.

Other than the controlling shareholder, these companies all had separate boards, Singh said.

AEML is within Adani Transmission (ATL), though the Qatar Investment Authority also holds a 24% stake. Carmichael belongs to Adani Enterprises (AEL).

“Carmichael belongs to a public company — it’s nothing to do with AEML, other than that they have one common shareholder,” Singh said. “If you set aside the shareholder directors, there is no common director between AEL and ATL.”

There is no company called Adani Group, but the group presents itself to investors as a group, as is clear from an investor presentation given by Adani Enterprises in Singapore on August 26 and 27, which refers to Adani Group.

Asked about this, Singh said: “We present it as a portfolio with a common philosophy of building an infrastructure and real asset platform. We also say that they are independently held companies with no cross-shareholdings, no inter-entity loans, and we make a specific point that they have independent management. The boards have different committees, for example.”

The offering circular for the AEML bond refers 48 times to “the Adani Group” and includes a ‘Description of the Adani Group’ on pages 203 to 204, including a diagram (see illustration above). These sections do not mention Carmichael.

“We can’t disclose about another publicly listed company,” said Singh.

Standard challenged

He said that Adani Airports Holding, which is due to bring a bond issue in the coming weeks, would disclose about Carmichael, because both of them are owned by Adani Enterprises.

He drew an analogy with the Tata Group, another Indian group with many subsidiaries, arguing that each of its companies was not expected to disclose about all the others.

“Are you willing to apply the same standard to every UK company?” Singh asked. “We understand what is going on — we are an emerging market economy, it’s easy to beat us around. We understand and it will continue that way. But at the same time, the SEC has standards.”

Adani had disclosed what was required by SEC rules, he argued. Demanding that it disclose more was applying double standards, since this would not be expected of other companies.

A UK law firm and the legal departments of all the lead managers had signed off the disclosures, he added.

“What do you believe is the cashflow of Carmichael?” Singh asked. “Zero so far. It’s not even a material cashflow for AEL. From a group point of view the entire commercial mining operation is less than 4% of cashflow, less than 5% of capex and less than 2.5% of our asset base.”

Material or not?

The AFII’s complaint argues that AEML’s connection with Carmichael is relevant and material, despite them being in different group companies, because of the highly controversial nature of the mine, which has caused many financial institutions to exclude financing it.

This could be seen as particularly important to disclose when issuing a sustainability-linked bond, which is explicitly linked to shifting from coal to renewable power.

“With an SLB the whole point is to get a specific group of investors,” Erlandsson said, meaning those interested in ESG issues, in this case reducing greenhouse gas emissions. “So sustainability disclosures are more important.”

Erlandsson also argues, though this is not emphasised in the formal complaint, that Carmichael is not separate from AEML in business reality, because they are both part of a network of companies in the energy value chain, which support and reinforce each other.

“One company mines coal, one ships it, one burns it, one distributes electricity,” he said. “We’re just asking them to say: ‘This is our value chain. We understand it’s problematic, we’re willing to change.’ I think Adani should be very upfront and say: ‘This is what we have — please help us do something better.’”

Singh rejected this argument, saying Carmichael coal would go to Adani Power, but not to Adani Transmission, which includes AEML.

“We have a large business called Adani Power, our thermal power generation business, which is also fully disclosed,” he said. “That is the coal user. One of Adani Power’s assets is based on the coast. The coastal power plant will use coal from Carmichael. The rest are hinterland plants, so it’s not economic.”

Adding rail freight costs to the cost of imported coal would make it unaffordable, he said. So Carmichael coal could only be used at that single plant at Mundra in Gujarat (pictured).

Singh picked up on one line in the AFII’s letter. After quoting Singh’s comment that Carmichael was “a support business for Adani Power”, the AFII added in brackets: “i.e., a support business for ATL”.

Singh said: “In this report he misattributes — I said it was very likely Adani Power will use coal from Carmichael. Adani Transmission is not a power company.”

AEML’s Dahanu coal-fired power station could not use Carmichael coal because of its inland position, Singh said. It is also scheduled to close in 2035.

“The whole substance of his claim is false,” Singh said.

Boxes empty and ticked

Singh downplayed the Vigeo Eiris revision of its SPO, saying VE had not issued a revision of its opinion, it had just failed to tick a box the first time. “Vigeo made a mistake, and then corrected it,” he said. “I don’t know who pointed it out. They said they were revising that element, and we said we didn’t have a problem with it.”

Asked whether VE had been correct with its first report or the second, Singh said: “I think they were correct the first time. [But] it would have been better for everybody if that level of checks were done and each box had been ticked.”

AIA, the insurance company listed in Hong Kong, had not invested in the AEML bond because of its involvement in thermal power, Singh said, but this was self-evident: it was explicit that AEML mainly used thermal power now and was transitioning to renewables.

Asked whether investors had asked about Carmichael when the AEML bond was being marketed, D Balasubramanyam, Adani’s group head of investor relations, said: “It did come up. We explained that AEML was not linked with it in business or ownership. The Carmichael question comes up in each of our roadshows.”

Willing to change

GlobalCapital asked Singh whether, since this issue had caused trouble, it might have been worthwhile for Adani to have disclosed about Carmichael in the AEML offering documents.

“We are long term investors in India’s largest infrastructure platform, with approximately $40bn of minority shareholders’ capital,” he said. “We issue compliance certificates to over 160 investors every six months. We as a principle, based on our risk and governance framework, want to make sure disclosures are correct in spirit and in law, and if we find anything that could be improved to protect investors and bondholders, most certainly we will make those improvements. Because ultimately, when we are attacked, there is the possibility of our investors losing money.

“So if that means if we add in the portfolio section of the offering circular of every issuer two lines about a non-operating coal mine, we will add that.”

But, he added: “Will it stop people like Ulf and Greta [Thunberg] from tweeting and saying things about us? We don’t think so, because they speak from the point of view of privilege, and that blinds them to the reality of the emerging world, and it is very difficult to take the blinkers of privilege off. We don’t believe anything will stop them saying ‘you’ve disclosed about Carmichael, now do something else’.”

Erlandsson said: “For somebody working closely to one of the biggest billionaires in the world to say that we, a small NGO, are doing it out of a sense of entitlement — it’s asymmetric.”

Singh said he did not believe attacks on Adani would stop, “because they’ve failed. The entire 350.org [environmental] organisation went after one mine to stop it and they have failed in every court in Australia, the government rejected them. They have lost the public battle also — now they will lose the battle here.”

Adani planned to issue an SEC registered deal, he said — a green bond from Adani Green Energy. SEC registration is held to need a higher standard of disclosure than 144A issuance, the standard that the AEML SLB was issued under.

Banks accused

Erlandsson said: “I’ll be very happy if they fulfil disclosure requirements — that’s what we’re asking for, and what the banks to whom they’ve been paying millions in fees should have told them. [Singh] should refocus his energy on those who didn’t give him the advice we did.”

The day before the bond was priced, on July 14, the AFII published a satirical blog post in which it called on AEML to set as a target for its SLB not to use any coal from Carmichael.

“There is a stated public opinion from my side with regard to the company, its linkage to Carmichael and how we think it’s detrimental,” said Erlandsson. “Given I had the information, it must have been in the knowledge base of all the banks and legal advisers — they should have done something about it.”

AEML and the banks could have disclosed the nature of its relationship with Carmichael, including that it would not consume Carmichael coal.

“The issuer should be upset that they have been poorly advised,” Erlandsson said. “I do think if there is frustration on the part of Adani, they should be going to the banks, not to the one who raised question marks, if they find that they are valid. And it’s extremely clear to me with regard to the second party opinion that didn’t disclose on coal or ESG controversies that [this is] a very material issue.”

Also, Erlandsson said, since the AFII’s blog post clearly explained that AEML had its own coal-fired power station, “how could Vigeo not have the capacity to [notice] it and revise the SPO instantaneously? And the fact that none of the banks [spotted] that the SPO was clearly misleading — I do feel that’s fairly improbable.”

Green and grey

Underlying the technical issues about disclosure is the basic fact that the Adani Group’s activities are diverse — and in the light of environmental consciousness, inconsistent. The group sees the potential of renewable energy and is investing heavily in it (pictured). However, it is also still expanding its coal activities. Investors in the group’s companies have to grapple with this issue.

Adani has a mining services business, which provides engineering and technical support for state-owned coal mines in India. This now works at three operating coal mines and one iron mine, which together produce 46m tonnes a year.

Under development or being planned are another six coal mines and one iron mine where Adani will provide services, totalling 71m tonnes a year.

In commercial mining, where Adani actually sells the coal, it has two operations being developed in India, 9m tonnes combined, and one in Indonesia called Bunyu, which produced 4m tonnes in 2017-18 and was set to grow.

Carmichael is now planned to produce 10m tonnes a year, though Adani has permission to go up to 27m.

Meanwhile, the International Energy Agency’s scenario for limiting climate change to 1.5°C indicates that all unabated coal power stations should be phased out in advanced economies by 2030 and everywhere by 2040. Global coal demand should halve by the end of this decade, it argues.

Part of a whole

GlobalCapital asked Singh why it was so important for the Adani Group to expand its coal mining operations, which were so controversial.

He said Adani’s commercial mines in India and Indonesia were small. “We will use the majority of coal from Carmichael at one of our largest existing thermal power plants,” he said. “It adds no new coal — it replaces coal we currently use. The net increase of coal consumption will be 3m to 5m tonnes. That will be sold commercially. This is 3m to 5m tonnes in a world that produces 8,000m tonnes annually.”

The group had decided in 2011-12 that it needed to shift its capex, he said, so about 75% of all its investments were now going into solar power and grids to transport it. About 20% was going on transport and logistics and only 5% on fossil fuel activities.

“It’s not something we don’t recognise,” Singh said. “We have shifted capex massively.”

In the next 12 months, Adani would do $9bn of capex, none of which would be for fossil fuels, he said. Carmichael no longer needed investment because it was complete, while Abbot Point’s bond would be for refinancing.

“It is a conundrum to me,” said Erlandsson, “why, when they have a very impressive business in many areas, they persist in building a thermal coal mine in 2021. From a valuation point of view, for the whole of Adani’s various companies, the drop in valuation from being associated with Carmichael is likely to be greater than it would cost them to shut it and write it off. You can grow a much stronger business — you just don’t have to open this coal mine.”

Green opportunities

“We fully understand the opposition to the mine,” said Singh. “We don’t understand the consistent attacks on our business that have nothing to do with the mine. AEML will have 70% renewable power by 2030 — that’s the same as Sweden. It’s broadly consistent with India’s commitment in the Paris Agreement and whatever commitment India makes in this COP. And it is 20% bigger than Sweden, because it has 12m customers. AEML is bringing a country the size of Sweden to be fully compliant and that is the company being attacked.”

Singh repeated that “very likely one of the takeaways we have is to modify the group disclosure in all our offering circulars.”

Besides praising Adani’s renewable power investments, the AFII sees other encouraging developments in India.

This month it published an article Market opportunity: Indian (green) bond issuance in EUR, prompted by a €300m green bond issued by state-owned Power Finance Corp in mid-September.

Noting that this was only the second Indian bond to have been issued in euros in recent years, the AFII said this was “a great opportunity for Indian corporations to issue in euro currency, and for euro investors to — when more supply comes — take positive exposure to a key geography for global climate change and the energy transition.”

Uncharted territory

The responsible investing industry appears to have done fairly little organised thinking about how to deal with ESG issues in corporate groups.

Certainly, practitioners do not have at their finger tips standard answers on the topic, as they do on other ESG questions, such as the greenium on green bonds — the amount of money a borrower saves by raising green debt rather than conventional — or whether divestment is a good idea.

Invited to by GlobalCapital, several large investment firms prominent in ESG were reluctant to comment on the issue.

Andreas Bjørbak Alnæs at Storebrand said: “We don’t punish companies downward — we don’t want to punish subsidiaries for what their parents are doing. But parent companies should be responsible for daughter companies.”

Asked whether a company issuing an SLB, like AEML, should disclose about ESG controversies at another group entity, Bjørbak Alnæs said: “Yes, it’s relevant information. It’s not something they are probably legally bound to highlight, but if you are issuing an SLB it’s definitely something investors should have information about.”

Josh Linder, senior credit analyst at APG Asset Management in New York, did not comment on Adani, but said: “APG evaluates sustainability-linked bonds, as well as green, social and sustainability bonds in the context of an issuer’s overall sustainability profile. ESG controversies that affect SLB issuers would be part of the evaluation process and looked at on a case-by-case basis. It could very well be a reason not to invest.”

He said APG would look at the source of the controversy, how material it was, and assess whether investing might be an opportunity for meaningful engagement.

“Is the issuer capable of becoming an ESG leader?” Linder said. “Are they using the SLB structure to facilitate a new sustainable trajectory? Analysing the specific context is very important.”

He did not want to comment on more detailed questions about how ESG investors decided whether issues at one group company should affect their view of another, or how much companies should disclose about affiliates.

Not in the Principles

The great majority of the guidance from the Green and Social Bond Principles focuses on the specific use of proceeds, not wider disclosures about an issuer. The GSBP organisation sees this as more of a regulatory issue than one of market best practice.

The Sustainability-Linked Bond Principles give detailed advice about the targets to which bonds are linked, and issuers are encouraged to position these within their overall sustainability policies as an organisation.

But controversies at companies are treated as lying in the realm of legal due diligence and risk factors, rather than being a product-related matter covered by the Principles.

And the SLBPs, like other manuals for responsible investing, do not address how to deal with complex corporate groups, in which more than one entity may issue debt and several may have different activities.

The Principles for Responsible Investment also does not appear to have explicit guidance on this issue.

Play it safe

Asked whether an SLB issuer should disclose about controversies elsewhere in its group, the head of sustainable finance at an investment bank in London said: “Generally speaking I think it is sensible to reference that to investors, because you are part of the same group and when it comes to ESG, it is quite common for there to be common policies, oversight and governance. If there are shortcomings, that is helpful information that you would imagine investors may flag — particularly because ESG rating agencies would likely aggregate it. The question is whether you should flag it or be ready to answer questions about it.”

He said ESG ratings were typically assigned at group level.

Another issue might be whether the controversy was relevant to the issuer attaining its targets under the SLB, the banker said.

“It’s one of the reasons SLBs are trickier in conglomerate situations,” he said. “We’ve been working with some. SLBs are generally about whole company transformation. If you’re raising money at one subsidiary, one can question how much impact it’s having on the wider group.”

A labelled bonds specialist said: “If an ESG issue is very significant and can affect the entire reputation of the group, it may also be right that it has to be disclosed. What I’m starting to see is that SLBs are working, by putting issuers in a situation where they do need to look more holistically at what they are doing, and this can be painful. The reality is there are problems and not enough has been done, especially in hard to abate sectors. Management will say ‘I want to do it’, but a light shining on the whole business can lead to uncomfortable dilemmas.”

Difficult questions

Asked about this issue, Sean Kidney, CEO of the Climate Bonds Initiative, said: “We can all make decisions about what’s beyond the pale, but we can’t make them if we don’t know some further information about matters that are material. [Disclosure] sounds like a good idea from investors’ perspective, but that doesn’t mean it’s going to make a big difference. We’ve got to make sure we don’t kid ourselves — [investors] moving out of one thing and into another is a bit like shifting deckchairs on the Titanic.”

But he said: “I would expect a group to be explaining all its businesses” so that investors could “understand the interdependency”.

Kidney himself brought up Adani, saying that he had been having “running discussions” with it, and Singh in particular. “They are arguing: ‘You’ve got to support our renewables division’ and our investors are saying: ‘You’ve got a huge coal mine’, so it’s challenging.”

He said the CBI had been “clear in public to applaud the growth of their renewables division. With any organisation, we will always give a mixture of plaudits and brickbats, depending on what they are doing.”

He believed Singh “sees himself as a change agent in Adani” and had been “largely responsible for the corporate shift to downplay coal”.

Kidney said: “It’s a company in transition — the question is, how quickly. They’ve got large coal plants — they need to find ways to close them in 15 years, not 25.”

The difficulty for investors — and investment banks — of reaching a clear view on the ESG characteristics of a diverse corporate group makes the need for research and activism in this area compelling, both on the general issues and specific companies.

“We don’t do it out of spite,” said Erlandsson. “Actually it’s because there’s something real there. It is a sense of public whistleblowing — which has never been a great career choice. I don’t like new thermal coal mines — neither do my children. If you’re going to do it, you play by the market rules or you are running around with a big liability. It’s the prerogative of Adani to do it, but they need to know there is opposition to this.”