The latest results of the European Central Bank (ECB)’s climate stress tests incorporated the energy performance of buildings as a contributing metric to determine banks’ resilience to climate shocks. It revealed that European banks’ mortgage books could be exposed to a higher credit risk because of this.

“The test was a learning exercise,” a source at CaixaBank tells Euromoney. “It enabled us to look transversally across our different portfolios, including the mortgages book.”

The Madrid-headquartered bank has the largest mortgage portfolio in Spain. Its book mirrors the quality of the overall housing stock in the country.

As legal frameworks across Europe adapt, it will become impossible to sell or rent properties with poor energy performance certificates (EPC) ratings.

In France, the recent Climate and Resilience Law requires properties to have at least a class F EPC by 2025, class E by 2028 and class D by 2034 to be rented out. Between 700,000 and 800,000 homes need to be renovated annually to adapt the national housing market, often referred to as a ‘passoire thermique’ or thermal sieve.

There is a risk that such ambitious targets could polarize the housing market.

“It’s great to see such ambitious targets set at the national level, but we might end up with a fragmented real-estate market that moves at different speeds,” acknowledges Pierre-Alix Binet, head of institutional and regulatory affairs at La Banque Postale.

A division of the market between compliant and non-compliant assets could lower prices for the least energy-efficient homes and reduce recovery expectations, according to a Fitch Ratings report.

Ageing stock

Energy leakage is largely due to the continent’s ageing housing stock. In Europe, about 55% of homes date back to pre-1960, and have poor energy efficiency as a result.

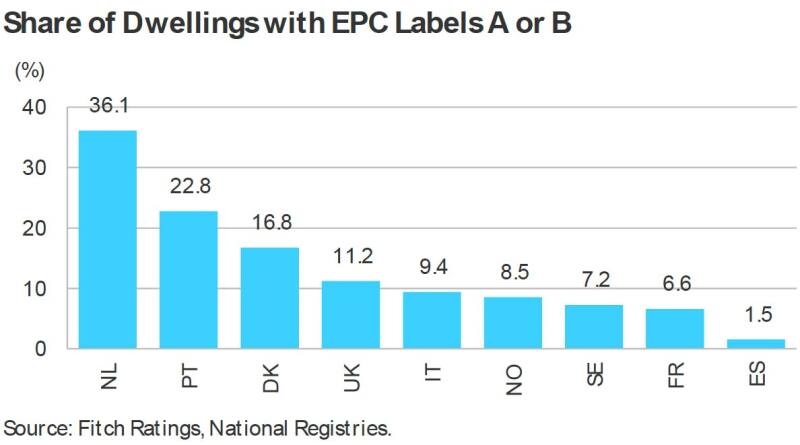

“The energy efficiency of Spanish buildings is low and that is a countrywide problem,” confirms the CaixaBank source. “Statistically speaking, around 50% of our mortgage book is in the lower tier and would need some renovation from an energy perspective.”

EU directives are evolving rapidly to address this. A revision of the energy performance of buildings directive (EPBD) specifies the EU’s timeline to have a fully decarbonized housing stock by 2050. The proposal sets minimum energy-performance standards to stimulate housing renovation, but allows member states to set national targets, according to their own EPC data.

The lack of data standardization across jurisdictions could also become problematic for bond issuance. If EPC data feeds into the quality of the green bond, investors need comparable data to rate the underlying collateral.

“For financial institutions to refinance loans on housing assets, they first need a clear definition of what those assets are. Having different rules for EPCs is a significant limitation in the comparison,” says Carmen Muñoz, global head of risk at Sustainable Fitch.

The data gap explains why the market is dominated by unsecured debt. For Muñoz, there are not enough green assets available for securitized loans.

“We’ve seen less issuance of structured finance products than traditional bonds,” she says, attributing this imbalance to limited incorporation of EPC information in the loan grading.

Some banks have found a way around this. “We have issued four green bonds so far and within them we include green buildings alongside other types of green assets, like renewable energy projects for example,” says the CaixaBank source. “This enables us to generate sufficient green collateral to issue the bond.”

Viva la renovation

If the EU is to meet its decarbonized housing target, homeowners need to borrow more. For Positive Money’s executive director Stanislas Jourdan, changing landlords’ opinion on taking on more debt could come from incentives within banking solutions.

Zero-coupon loans specifically for energy-driven renovations, for example, could stimulate the market. “This kind of product is needed to incentivize people to renovate,” says Jourdan. “People want to see the benefits of their investments immediately and pay back later.”

It’s a different way of engineering financing solutions that are necessary to make up for public budget constraints

These types of incentives already exist. In Belgium, eligible parties are allowed to borrow from €500 to €25,000 at preferential rates for energy-improving works at their residences located in the Brussels region. In France, the zero-rated eco-loan scheme enables homeowners to borrow up to €30,000 refundable for 15 years after renovation works.

La Banque Postale has been working on adapting its offerings, including the ‘prêt Avance rénovation’, which recognizes the higher financial needs of vulnerable households. This mortgage solution facilitates clients’ access to a line of credit backed by the asset itself, whereby the funds for renovation are immediately available, but the client can pay back the loan when the asset is sold or inherited.

Skender Sahiti-Manzoni, head of sustainable commitments and stakeholder engagement at La Banque Postale, adds: “We are not yet including EPC data in our credit risk assessments, but we do consider the client’s financial capacity if they intend to buy a home with a poor EPC to ensure that they would then be able to renovate it.”

Affordability concerns

These products raise questions of affordability. The potential long-term savings on energy bills after renovation might be an incentive for households, but some mortgagers of inefficient properties might be priced out of improving their homes.

“We know that low-income people are more exposed to energy price shocks because of the quality of the home,” says Positive Money’s Jourdan. “They also tend to be more leveraged, so there is a higher risk for banks.”

Like its European peers, CaixaBank has been using EPC data to identify homes with the lowest rating. “We now have insight on collateralized housing stock of our mortgage portfolio and can offer loans to the clients who need it first,” the source says.

Public funding to landlords in the form of grants has also helped stimulate the market. The UK’s Green Homes Grant, for example, has made £2 billion of capital available to homeowners to get up to two-thirds of renovation costs linked to energy efficiency covered by the government.

But with so many homes to renovate, most of the funding will have to come from the banking sector.

“It’s a different way of engineering financing solutions that are necessary to make up for public budget constraints,” says La Banque Postale’s Sahiti-Manzoni, adding that the solutions are tailored to ensure that households can be resilient in the changing legal environment.

It also remains to be seen whether regulators can ensure that EPC ratings are robust and not falsified. In addition to establishing benchmarks, legislators need the means to control EPC measurements.

“If you’re basing a whole set of regulation on a specific standard, that standard needs to be respected,” adds Binet.

For banks, tapping into the commercial potential of this form of lending could reduce the risk of homes becoming stranded assets as energy-performance standards are tightened.