Next week, on July 29, new rules come into effect designed to encourage more companies to launch initial public offerings in the UK equity market. The UK’s Financial Conduct Authority describes this as the biggest change to the listing regime in over 30 years.

It is a desperate gamble.

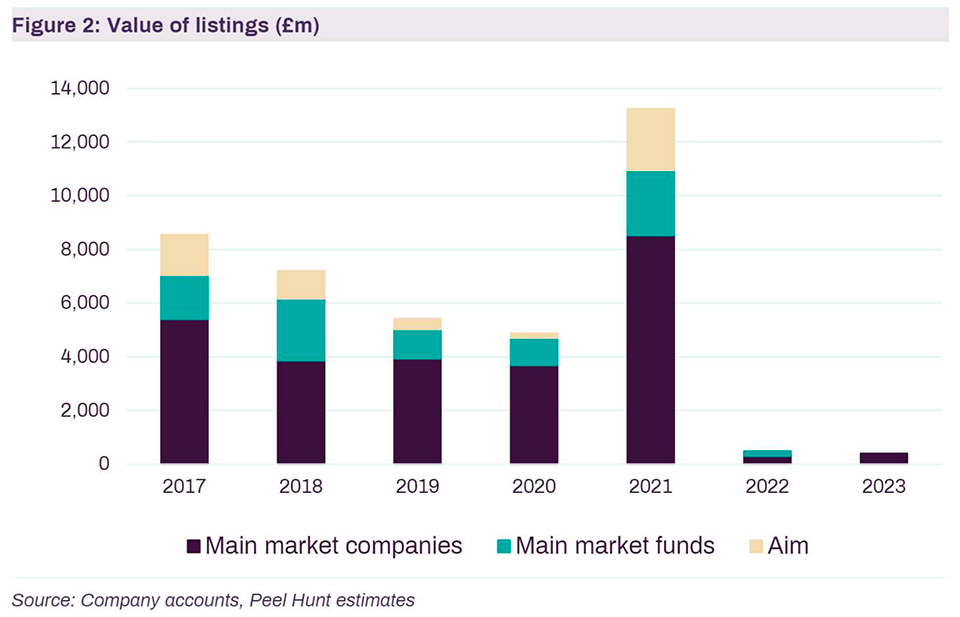

The new rules have been under development since the Hill review, launched in November 2020. Back then, ministers in the government of Boris Johnson were struggling to understand why the UK had accounted for just 5% of global IPO volume over the five years from 2015 and why the number of UK listed companies had fallen by 40% since 2008.

The new rules – pushed through in the first days of the new Labour government with a cursory blessing from chancellor Rachel Reeves that they will bring the UK into line with international counterparts – have been developed by achieving consensus among one, admittedly fairly disparate, group. That is issuing companies, which tend to dislike regulation, and their armies of advisers – bankers, lawyers, brokers, exchange officials – intermediaries that all benefit financially from more deals, even if they turn out to be bad ones for investors.

Ignored voices

Dame Julia Hoggett, chief executive of the London Stock Exchange, might claim it has been heartening to see the entire ecosystem come together behind a new listing regime that better supports companies’ growth ambitions. But the most important voices have been ignored.

The University Superannuation Scheme (USS) is the biggest pension fund in the UK. It allocates 46% of its £75.5 billion of assets under management to its home market. It made clear in consultations on the effectiveness of primary markets its strong opposition to dilution of key investor protections and shareholder rights, and it called for protection of the principle of one-share, one vote.

The new regime removes obstacles to dual-class share structures in an effort to appeal to technology company founders that may want to cash out early but still retain voting control.

The sell side has managed to paint investors as the bad guys in the UK’s decline as a centre for listings

The UK’s old two-tier regime of premium and standard listings meant that if a founder like Matthew Moulding wanted to list The Hut Group (THG), a company he had built, while still retaining control, it would remain on the lesser standard segment and so outside the main stock market indices.

The UK is now doing away with this separation and, as long as 5% of voting control is open to public investors in the free float, a company can go into the indices, where passive money has to take exposure, even while an individual with modest economic interest still exercises majority control.

Shareholders no longer have the right to vote on related-party transactions, for example, shifting certain assets into a different company.

The sell side has managed to paint investors as the bad guys in the UK’s decline as a centre for listings, for having diversified away from UK equities into overseas markets and other asset classes.

But targeting the new rules at prospective listing candidates looks like treating the symptom rather than the disease.

Companies are no longer listing in the UK – and many are delisting – because investors have moved away. Reducing investor protections is a bad way of attracting them back.

Caroline Escott, acting head of sustainable ownership at Railpen, says the £34 billion pension scheme is deeply disappointed at the new listing rules, after it presented compelling evidence in support of the benefits of robust investor protections, both to the UK as a global financial centre and to everyday savers. This was not heeded.

The committee to save the UK equity market will no doubt say that something had to be done. But if the quality of companies listing in the UK now declines, the outcome for investors will get even worse.

Shares in a fast-fashion company that outsources the manufacture of cheap clothing to provinces in China with no protection for workers… anyone?